Spares Packaging

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

We Are Bauer Media the Uk's Most Influential Media

MEDIA GROUP Magazine Advertising Specifications WE ARE BAUER MEDIA 25 Million People. 107 brands. Radio, Digital, TV, Magazines, Live. THE UK’S MOST INFLUENTIAL MEDIA BRAND NETWORK 1 Spec Sheets_20thJuly2020_All_Mags | 03/04/2020 MEDIA GROUP Magazine Brands Click on Magazine to take you to correct page AM ����������������������������������������������������5 MODEL RAIL ����������������������������������������5 ANGLING TIMES ���������������������������������4 MOJO ������������������������������������������������6 ARROW WORDS ��������������������������������7 MOTOR CYCLE NEWS �������������������������3 BELLA MAGAZINE �������������������������������6 PILOT TV ���������������������������������������������6 BELLA MAGAZINE MONTHLY ���������������6 PRACTICAL CLASSICS ��������������������������3 BIKE ���������������������������������������������������3 PRACTICAL SPORTSBIKES ���������������������3 BIRDWATCHING ����������������������������������5 PUZZLE SELECTION �����������������������������7 BUILT ��������������������������������������������������3 Q �������������������������������������������������������6 CAR ���������������������������������������������������3 RAIL����������������������������������������������������5 CARPFEED ������������������������������������������4 RIDE ���������������������������������������������������3 CLASSIC BIKE ��������������������������������������3 SPIRIT & DESTINY ��������������������������������6 CLASSIC CAR WEEKLY �������������������������3 STEAM RAILWAY ���������������������������������5 CLASSIC CARS ������������������������������������3 -

United Kingdom Distribution Points

United Kingdom Distribution to national, regional and trade media, including national and regional newspapers, radio and television stations, through proprietary and news agency network of The Press Association (PA). In addition, the circuit features the following complimentary added-value services: . Posting to online services and portals with a complimentary ReleaseWatch report. Coverage on PR Newswire for Journalists, PR Newswire's media-only website and custom push email service reaching over 100,000 registered journalists from 140 countries and in 17 different languages. Distribution of listed company news to financial professionals around the world via Thomson Reuters, Bloomberg and proprietary networks. Releases are translated and distributed in English via PA. 3,298 Points Country Media Point Media Type United Adones Blogger Kingdom United Airlines Angel Blogger Kingdom United Alien Prequel News Blog Blogger Kingdom United Beauty & Fashion World Blogger Kingdom United BellaBacchante Blogger Kingdom United Blog Me Beautiful Blogger Kingdom United BrandFixion Blogger Kingdom United Car Design News Blogger Kingdom United Corp Websites Blogger Kingdom United Create MILK Blogger Kingdom United Diamond Lounge Blogger Kingdom United Drink Brands.com Blogger Kingdom United English News Blogger Kingdom United ExchangeWire.com Blogger Kingdom United Finacial Times Blogger Kingdom United gabrielleteare.com/blog Blogger Kingdom United girlsngadgets.com Blogger Kingdom United Gizable Blogger Kingdom United http://clashcityrocker.blogg.no Blogger -

ABC Consumer Magazine Concurrent Release - Dec 2007 This Page Is Intentionally Blank Section 1

December 2007 Industry agreed measurement CONSUMER MAGAZINES CONCURRENT RELEASE This page is intentionally blank Contents Section Contents Page No 01 ABC Top 100 Actively Purchased Magazines (UK/RoI) 05 02 ABC Top 100 Magazines - Total Average Net Circulation/Distribution 09 03 ABC Top 100 Magazines - Total Average Net Circulation/Distribution (UK/RoI) 13 04 ABC Top 100 Magazines - Circulation/Distribution Increases/Decreases (UK/RoI) 17 05 ABC Top 100 Magazines - Actively Purchased Increases/Decreases (UK/RoI) 21 06 ABC Top 100 Magazines - Newstrade and Single Copy Sales (UK/RoI) 25 07 ABC Top 100 Magazines - Single Copy Subscription Sales (UK/RoI) 29 08 ABC Market Sectors - Total Average Net Circulation/Distribution 33 09 ABC Market Sectors - Percentage Change 37 10 ABC Trend Data - Total Average Net Circulation/Distribution by title within Market Sector 41 11 ABC Market Sector Circulation/Distribution Analysis 61 12 ABC Publishers and their Publications 93 13 ABC Alphabetical Title Listing 115 14 ABC Group Certificates Ranked by Total Average Net Circulation/Distribution 131 15 ABC Group Certificates and their Components 133 16 ABC Debut Titles 139 17 ABC Issue Variance Report 143 Notes Magazines Included in this Report Inclusion in this report is optional and includes those magazines which have submitted their circulation/distribution figures by the deadline. Circulation/Distribution In this report no distinction is made between Circulation and Distribution in tables which include a Total Average Net figure. Where the Monitored Free Distribution element of a title’s claimed certified copies is more than 80% of the Total Average Net, a Certificate of Distribution has been issued. -

Ipso Annual Statement

Bauer Consumer Media Limited (“BCML”) and H. Bauer Publishing (“H. Bauer”) IPSO ANNUAL STATEMENT 01 January to 31 December 2017 (the “Reported Period“) Bauer Consumer Media Ltd company number: 01176085 Registered office Media House Peterborough Business Park, Lynch Wood, Peterborough, United Kingdom, PE2 6EA. CONTENTS 1. Introduction A. Bauer Consumer Media Limied (“BCML”) B. H. Bauer Publishing (“H. Bauer”) 2. Editorial Standards 3. Our Complaints-Handling Process 4. Our Training Process 5. Our record on compliance APPENDIX 1 – BCML AND H. BAUER EDITORIAL COMPLAINTS POLICY APPENDIX 2 – BAUER WEBSITE AND MASTHEAD COMPLAINTS INFORMATION 1 1. INTRODUCTION Bauer Media Group consists of two publishing arms, Bauer Consumer Media Limited and H. Bauer Publishing. Both companies are UK based companies of the Bauer Media Group, a worldwide media empire offering over 600 magazines in 16 countries, as well as online platforms, TV channels, and radio stations. A. Bauer Consumer Media Limied (“BCML”) BCML joined the Bauer Media Group in January 2008 following the acquisition of Emap PLC’s consumer and specialist magazine, radio, online and digital businesses. Our magazine heritage stretches back to 1953 with the launch of Angling Times and the acquisition in 1956 of Motor Cycle News, both still iconic brands within our portfolio. Continuing its history of magazine launches, Closer was launched in 2002 and Britain’s first weekly glossy, Grazia, was launched in 2005. The most recent additions to our portfolio came with the launches of The Debrief, a digital only brand, in February 2014, and Planet Rock magazine in May 2017. Today, BCML comprises 80 influential brand names, covering a diverse range of interests including: Empire, Mojo, Q, Heat, Parkers, Match, Car and Yours. -

Contents 1945

500 Owners Association MOTOR SPORT Magazine Clippings - 1940’s Issued: 4th March 2015 Notes on 500 and 500-related references This paper is an attempt to record every single 500-related reference from the entire run of the magazine. It includes articles, references in event reports, For Sale advertisements. It also tries to include details that are relevant to the context of the 500 movement, such as clubs, organisation of the sport, and the development of venues. The only area where it is limited is when covering the careers of 500 drivers before or after their time in the movement Status: All magazines in the time period have been fully catalogued. Notes On : • Magazine issues with no entry & light shading are not available for cataloguing. We would be grateful if you could volunteer to add any missing issues. • Every effort has been made to find references, including references in general and classified advertisements. However, it is quite possible that some may have been missed whether because they are very obscure, apparently irrelevant, or just human error. • Transcription Style: • Text has been transcribed verbatim (including spelling errors), with only modern grammar substituted for contractions (e.g. “S Moss” for “S.Moss”; “ftd” for f.t.d.) • “(sic)” notation may have been used where relevant in text, and is a transcriber’s note rather than the source text. • For longer articles, only pieces of note are transcribed. The ellipsis (“… “) before a sentence indicates that text deemed irrelevant has been skipped (which could run to many paragraphs, e.g. reports of other classes in an event report). -

Change Your Life in 2018

16-PAGE RIDE MOREPULLOUT CHANGE YOUR LIFE IN 2018 POWERED BY: IN ASSOCIATION WITH MCN’S TRUSTED PARTNERS l Essential events l 10 Amazing roads l 61 great destinations l Real-life stories www.motorcyclenews.com #MCNwednesday 02 # RIDE MILES TO JOIN, LOG ON TO facebook.com/groups/ride5000miles March 21 2018 03 5 GREAT RIDES CONTENTS PERFECT BIKING YEAR RIDE MORE, BE HAPPIER DESTINATION PLANNER 8 The best events, bike meets, tea stops and race #RIDE MILES meetings 12 4 Pullout It’s never too late to start planning brilliant planner to destinations and events for the biking year ahead Five incredible 5000 rides that’ll inspire you put on your to get out and about on your bike garage wall 10 GREAT RIDES TRIPS OF A LIFETIME SIGN UP NOW! R5K NUMBERS Meet new friends, find new #ride5000miles members nominate ten easy routes, broaden your horizons weekend routes to help you build your mileage 6 and have your best year yet 14 How just riding 13 sing your bike more is a but if you use the target to spend more the challenge in the last year and our 11 sure-fire route to happiness time with your biking mates, or head Facebook site has become a real com- miles a day will be – and that’s a fact. Boffins out on a trip you’ve always fancied, it’ll munity – a hub for route-sharing, tips enough to hit your in white coats have proven improve your life, too. and encouragement. It’s an inspiration 5000-mile target Calais to Kazakhstan? Don’t mind if I do. -

The Birmingham Small Arms Company Limited (BSA) Was A

Norton Villiers Triumph Norton Villiers/BSA factory in Small Heath in its heyday _____________________________________________________________________ Norton Villiers Triumph was a British motorcycle manufacturer, formed by the British Government to continue the UK motorcycling industry, but the company eventually failed. Triumph had been owned by the BSA Group since 1951, but by 1972 the merged BSA-Triumph group was in serious financial trouble. British Government policy at the time was to save strategic industries with tax payers' money, and as BSA-Triumph had won the Queen's Awards for Exports a few years earlier, the industry was deemed 'strategic' enough for financial support. The Conservative Government under Ted Heath concluded to bail out the company, provided that to compete with the Japanese it merged with financially troubled Norton Villiers (the remains of Associated Motor Cycles, which had gone bust in 1966), a subsidiary of British engineering conglomerate Manganese Bronze. The merged company was created in 1973, with Manganese Bronze exchanging the motorcycle parts of Norton Villiers in exchange for the non-motorcycling bits of the BSA Group—mainly Carbodies, the builder of the Austin FX4 London taxi: the classic "black cab." As BSA was both a failed company and a solely British-known brand (the company's products had always been most successfully marketed in North America under the Triumph brand), the new conglomerate was called Norton Villiers Triumph—being effectively the consolidation of the entire once-dominant British motorcycle industry. NVT inherited four motorcycle factories—Small Heath (ex-BSA); Andover and Wolverhampton (Norton); and Meriden (Triumph). Meriden was the most modern of the four. -

Triumph Motorcycles Timeline the Glory Years, 1963-1972

6/18/2021 Triumph Motorcycles Timeline: The Glory Years, 1963-1972 Triumph Motorcycles timeline 1963-1972: The Glory Years See bottom of page for links to other eras in Triumph's history New: Post your comments, opinions, and ask questions on my new FORUM. Tiger 90, high performance 350 3TA introduced, similar to T100S/S. All 650s, (including Bonnies, 1963 Tbirds, TR6, Trophy) are built with a new unit construction engine/gear box. Tina T10, 100cc scooter with automatic transmission introduced (designed by Turner). The US-only TR6SC, a pure desert racer with straight pipes, was produced: basically a single-carb T120, very fast. 650s all get new coil ignition. First year for T120 unit construction models. The Bonnie undergoes numerous and significant upgrades to its engine, gearbox, transmission and frame (after toying with a duplex design, Triumph instead made a larger diameter downtube to combat wobble and weave). A special TT model (T120C/TT) is produced until 1967 for the USA, due to the encouragement of Bill Johnson, of Johnson Motors ("Jo-Mo"). This is a stripped-down racing model, only made until 1966 for the US market. Two US dealers on a camping trip come up with the idea for the T20M Mountain Cub, combining Tiger Cub, Sports Cub and trials Cub parts. First sold in USA in 1964, proves very successful. BSA closes the Ariel factory at Selly Oak. The last Ariels in production, the Leader and Arrow, are manufactured at BSA's factory in Small Heath until 1965. Norton Atlas released. AMC acquires James. Norman ceases production. -

R.A.C. British Hill Climb Championship Meeting 10 September 1967 Player’S

R.A.C. BRITISH HILL CLIMB CHAMPIONSHIP MEETING 10 SEPTEMBER 1967 PLAYER’S give you guoranteed quolity.plus gifts, foi 3'6 flitei. 4'2 plain l l l l l Z TO f6 1 ll.'l !■ B, ■\>XM ^ € 1 Tony Marsh, Hill Climb Champion 1955/56/57/65/66. Photograph by Viki Heppenstall. THE YORKSHIRE CENTRE OF The British Automobile Racing Club Ltd. WELCOME YOU TO THE THE TWENTY-FIFTH HAREWOOD HILL CLIMB INCORPORATING THE R.A.C. BRITISH HILL CLIMB CHAMPIONSHIP R.A.C. PERMIT No. RS/3443 SUNDAY, 10‘h SEPTEMBER, 1967 COMMENCE 1-00 P.M. HELD AT STOCKTON FARM, HAREWOOD, LEEDS by kind permission of Arnold Burton, Esq. WARNING TO THE PUBLIC Motor racing is dangerous and persons attending this meeting do so entirely at their own risk. It is a condition of admission that all persons having any connection with the promotion and/or organisation and/or conduct of the meeting, including the owners of the land and the drivers and owners of the vehicles, are absolved from all liability arising out of accidents, howsoever caused, resulting in damage and/or personal injury, DOGS ARE NOT ALLOWED AT THE HILL CLIMB. 3 ß A V C i i N e ^ leiH IPIEKirOKMÄNCIE CAIK §IH€W, N€Y.4 -1I2” s \ M K iN G m r s You must see this show at Ringways ! Absolutely everything to Interest the ‘enthusiast', . Several current FORMULA II & III cars (and probably a FORMULA I) . A giant Le Mans winning 7 LITRE FORD. The 'Broadspeed' ANGLIA . Sir John Whitmore’s European Championship Winning LOTUS, plus many more award winning cars. -

To Download The

Las Cruces Transportation July 9 - 15, 2021 YOUR RIDE. YOUR WAY. Las Cruces Shuttle – Taxi Charter – Courier Veteran Owned and Operated Since 1985. Cecily Strong and Keegan-Michael Key star in “Schmigadoon!,” premiering Friday on Apple TV+. Call us to make a reservation today! We are Covid-19 Safe-Practice Compliant Call us at 800-288-1784 or for more details 2 x 5.5” ad visit www.lascrucesshuttle.com PHARMACY Providing local, full-service pharmacy needs for all types of facilities. • Assisted Living • Hospice • Long-term care • DD Waiver • Skilled Nursing and more It’s singing! It’s dancing! Call us today! 575-288-1412 Ask your provider if they utilize the many benefits of XR Innovations, such as: Blister or multi-dose packaging, OTC’s & FREE Delivery. It’s ‘Schmigadoon!’ Learn more about what we do at www.rxinnovationslc.net2 x 4” ad 2 Your Bulletin TV & Entertainment pullout section July 9 - 15, 2021 What’s Available NOW On “The Mighty Ones” “Movie: Exit Plan” “McCartney 3,2,1” “This Way Up” This co-production of Germany, Denmark and Paul McCartney is among the executive A flood, a home makeover and a new feathery The second season of this British comedy from Norway stars Nicolaj Coster-Waldau (“Game of producers of this six-episode documentary friend are ahead for offbeat pals Rocksy, Twig, writer, creator and star Aisling Bea finds her Thrones”) as Max, an insurance adjuster in the series that features intimate and revealing Leaf and Very Berry in their unkempt backyard character of Aine getting back up to speed midst of an existential crisis, who checks into a examinations of musical history from two living domain as this animated comedy returns for following her nervous breakdown, leaving rehab secret hotel that specializes in elaborate assisted legends — McCartney and acclaimed producer its second season. -

Periodicals by Title

I think this is now the largest list of books and magazines in the world on Motor Vehicles. I think I maybe the only person trying to find and document every Book and Magazine on Motor Vehicles. This is a 70+ year trip for me all over the world. Some people have called this an obsession, I call it my passion. This has been a hobby for me since I was about 10 years old. I don’t work on it everyday. I don’t do this for money. I don't have any financial help. I have no books or magazines for sale or trade. I do depend on other Book and Magazine collectors for information on titles I don’t have. Do you know of a Book, Magazine, Newsletter or Newspaper not on my list?? Is my information up to date?? If not can you help bring it up to date?? I depend on WORD-OF-MOUTH advertising so please tell your friends and anyone else that you think would have an interest in collecting books and magazines on motor vehicles. I am giving my Book and Magazine Lists to Richard Carroll to publish on his web - site at www.21speedwayshop.com take a look.. All I am collecting now is any issue of a title. If you are the first to send me a copy of a magazine I don’t have I will thank you with a mention under the title. Because of two strokes and a back injury from falling down the stairs this is about all I can do now. -

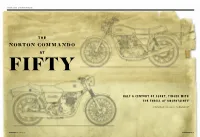

Norton Commando

norton Commando T H E NORTON COMMANDO AT FIFTY HALF A CENTURY OF GLORY, TINGED WITH THE THRILL OF UNCERTAINTY By Peter Egan Illustrations by Mick Ofield 44 CYCLE WORLD DECEMBER 2017 CYCLEWORLD.COM 45 norton Commando Illustrations and modeling of the never-produced Commando Mk 4 from the sketchbook of Mick Ofield, Norton employee 1972-'80. Merger brought parts sharing with Triumph models. “love/hate relationship” with Nortons, but it might be more accurately de- scribed as a “love/hope relationship.” I know all their foibles but keep thinking that just the right upgrades to modern materials, electronics, and sealants will render them virtually as useful and reli- and then 850 Roadsters of the early ’70s the Whitworth wrenches I still own. able as any modern motorcycle. And I to win my heart. I spent hours gazing Later that year, the Commando seized know people who have made that theory at those full-color Commando ads in- and bent an exhaust valve in Montana work for them. My friend Bill Getty, who side the front cover of every major bike while Barb and I were attempting a ride owns a British parts business called JRC magazine, charmed by the pure ele- from Wisconsin to Seattle, and we had Engineering, has now put 130,000 miles mental beauty of the bike and of course to ship the bike home from Missoula in a on his 1974 850. the beauty of the “Norton Girl” who Bekins moving van, continuing the trip And of course Editor-in-Chief Mark stood alluringly nearby, pouting at me by bus and train.