Cantor and Infinite Sets Galileo and the Infinite

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Is Uncountable the Open Interval (0, 1)

Section 2.4:R is uncountable (0, 1) is uncountable This assertion and its proof date back to the 1890’s and to Georg Cantor. The proof is often referred to as “Cantor’s diagonal argument” and applies in more general contexts than we will see in these notes. Our goal in this section is to show that the setR of real numbers is uncountable or non-denumerable; this means that its elements cannot be listed, or cannot be put in bijective correspondence with the natural numbers. We saw at the end of Section 2.3 that R has the same cardinality as the interval ( π , π ), or the interval ( 1, 1), or the interval (0, 1). We will − 2 2 − show that the open interval (0, 1) is uncountable. Georg Cantor : born in St Petersburg (1845), died in Halle (1918) Theorem 42 The open interval (0, 1) is not a countable set. Dr Rachel Quinlan MA180/MA186/MA190 Calculus R is uncountable 143 / 222 Dr Rachel Quinlan MA180/MA186/MA190 Calculus R is uncountable 144 / 222 The open interval (0, 1) is not a countable set A hypothetical bijective correspondence Our goal is to show that the interval (0, 1) cannot be put in bijective correspondence with the setN of natural numbers. Our strategy is to We recall precisely what this set is. show that no attempt at constructing a bijective correspondence between It consists of all real numbers that are greater than zero and less these two sets can ever be complete; it can never involve all the real than 1, or equivalently of all the points on the number line that are numbers in the interval (0, 1) no matter how it is devised. -

Section 4.2 Counting

Section 4.2 Counting CS 130 – Discrete Structures Counting: Multiplication Principle • The idea is to find out how many members are present in a finite set • Multiplication Principle: If there are n possible outcomes for a first event and m possible outcomes for a second event, then there are n*m possible outcomes for the sequence of two events. • From the multiplication principle, it follows that for 2 sets A and B, |A x B| = |A|x|B| – A x B consists of all ordered pairs with first component from A and second component from B CS 130 – Discrete Structures 27 Examples • How many four digit number can there be if repetitions of numbers is allowed? • And if repetition of numbers is not allowed? • If a man has 4 suits, 8 shirts and 5 ties, how many outfits can he put together? CS 130 – Discrete Structures 28 Counting: Addition Principle • Addition Principle: If A and B are disjoint events with n and m outcomes, respectively, then the total number of possible outcomes for event “A or B” is n+m • If A and B are disjoint sets, then |A B| = |A| + |B| using the addition principle • Example: A customer wants to purchase a vehicle from a dealer. The dealer has 23 autos and 14 trucks in stock. How many selections does the customer have? CS 130 – Discrete Structures 29 More On Addition Principle • If A and B are disjoint sets, then |A B| = |A| + |B| • Prove that if A and B are finite sets then |A-B| = |A| - |A B| and |A-B| = |A| - |B| if B A (A-B) (A B) = (A B) (A B) = A (B B) = A U = A Also, A-B and A B are disjoint sets, therefore using the addition principle, |A| = | (A-B) (A B) | = |A-B| + |A B| Hence, |A-B| = |A| - |A B| If B A, then A B = B Hence, |A-B| = |A| - |B| CS 130 – Discrete Structures 30 Using Principles Together • How many four-digit numbers begin with a 4 or a 5 • How many three-digit integers (numbers between 100 and 999 inclusive) are even? • Suppose the last four digit of a telephone number must include at least one repeated digit. -

180: Counting Techniques

180: Counting Techniques In the following exercise we demonstrate the use of a few fundamental counting principles, namely the addition, multiplication, complementary, and inclusion-exclusion principles. While none of the principles are particular complicated in their own right, it does take some practice to become familiar with them, and recognise when they are applicable. I have attempted to indicate where alternate approaches are possible (and reasonable). Problem: Assume n ≥ 2 and m ≥ 1. Count the number of functions f :[n] ! [m] (i) in total. (ii) such that f(1) = 1 or f(2) = 1. (iii) with minx2[n] f(x) ≤ 5. (iv) such that f(1) ≥ f(2). (v) that are strictly increasing; that is, whenever x < y, f(x) < f(y). (vi) that are one-to-one (injective). (vii) that are onto (surjective). (viii) that are bijections. (ix) such that f(x) + f(y) is even for every x; y 2 [n]. (x) with maxx2[n] f(x) = minx2[n] f(x) + 1. Solution: (i) A function f :[n] ! [m] assigns for every integer 1 ≤ x ≤ n an integer 1 ≤ f(x) ≤ m. For each integer x, we have m options. As we make n such choices (independently), the total number of functions is m × m × : : : m = mn. (ii) (We assume n ≥ 2.) Let A1 be the set of functions with f(1) = 1, and A2 the set of functions with f(2) = 1. Then A1 [ A2 represents those functions with f(1) = 1 or f(2) = 1, which is precisely what we need to count. We have jA1 [ A2j = jA1j + jA2j − jA1 \ A2j. -

Cantor on Infinity in Nature, Number, and the Divine Mind

Cantor on Infinity in Nature, Number, and the Divine Mind Anne Newstead Abstract. The mathematician Georg Cantor strongly believed in the existence of actually infinite numbers and sets. Cantor’s “actualism” went against the Aristote- lian tradition in metaphysics and mathematics. Under the pressures to defend his theory, his metaphysics changed from Spinozistic monism to Leibnizian volunta- rist dualism. The factor motivating this change was two-fold: the desire to avoid antinomies associated with the notion of a universal collection and the desire to avoid the heresy of necessitarian pantheism. We document the changes in Can- tor’s thought with reference to his main philosophical-mathematical treatise, the Grundlagen (1883) as well as with reference to his article, “Über die verschiedenen Standpunkte in bezug auf das aktuelle Unendliche” (“Concerning Various Perspec- tives on the Actual Infinite”) (1885). I. he Philosophical Reception of Cantor’s Ideas. Georg Cantor’s dis- covery of transfinite numbers was revolutionary. Bertrand Russell Tdescribed it thus: The mathematical theory of infinity may almost be said to begin with Cantor. The infinitesimal Calculus, though it cannot wholly dispense with infinity, has as few dealings with it as possible, and contrives to hide it away before facing the world Cantor has abandoned this cowardly policy, and has brought the skeleton out of its cupboard. He has been emboldened on this course by denying that it is a skeleton. Indeed, like many other skeletons, it was wholly dependent on its cupboard, and vanished in the light of day.1 1Bertrand Russell, The Principles of Mathematics (London: Routledge, 1992 [1903]), 304. -

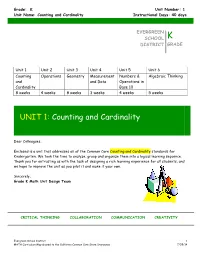

UNIT 1: Counting and Cardinality

Grade: K Unit Number: 1 Unit Name: Counting and Cardinality Instructional Days: 40 days EVERGREEN SCHOOL K DISTRICT GRADE Unit 1 Unit 2 Unit 3 Unit 4 Unit 5 Unit 6 Counting Operations Geometry Measurement Numbers & Algebraic Thinking and and Data Operations in Cardinality Base 10 8 weeks 4 weeks 8 weeks 3 weeks 4 weeks 5 weeks UNIT 1: Counting and Cardinality Dear Colleagues, Enclosed is a unit that addresses all of the Common Core Counting and Cardinality standards for Kindergarten. We took the time to analyze, group and organize them into a logical learning sequence. Thank you for entrusting us with the task of designing a rich learning experience for all students, and we hope to improve the unit as you pilot it and make it your own. Sincerely, Grade K Math Unit Design Team CRITICAL THINKING COLLABORATION COMMUNICATION CREATIVITY Evergreen School District 1 MATH Curriculum Map aligned to the California Common Core State Standards 7/29/14 Grade: K Unit Number: 1 Unit Name: Counting and Cardinality Instructional Days: 40 days UNIT 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Overview of the grade K Mathematics Program . 3 Essential Standards . 4 Emphasized Mathematical Practices . 4 Enduring Understandings & Essential Questions . 5 Chapter Overviews . 6 Chapter 1 . 8 Chapter 2 . 9 Chapter 3 . 10 Chapter 4 . 11 End-of-Unit Performance Task . 12 Appendices . 13 Evergreen School District 2 MATH Curriculum Map aligned to the California Common Core State Standards 7/29/14 Grade: K Unit Number: 1 Unit Name: Counting and Cardinality Instructional Days: 40 days Overview of the Grade K Mathematics Program UNIT NAME APPROX. -

Cardinality of Sets

Cardinality of Sets MAT231 Transition to Higher Mathematics Fall 2014 MAT231 (Transition to Higher Math) Cardinality of Sets Fall 2014 1 / 15 Outline 1 Sets with Equal Cardinality 2 Countable and Uncountable Sets MAT231 (Transition to Higher Math) Cardinality of Sets Fall 2014 2 / 15 Sets with Equal Cardinality Definition Two sets A and B have the same cardinality, written jAj = jBj, if there exists a bijective function f : A ! B. If no such bijective function exists, then the sets have unequal cardinalities, that is, jAj 6= jBj. Another way to say this is that jAj = jBj if there is a one-to-one correspondence between the elements of A and the elements of B. For example, to show that the set A = f1; 2; 3; 4g and the set B = {♠; ~; }; |g have the same cardinality it is sufficient to construct a bijective function between them. 1 2 3 4 ♠ ~ } | MAT231 (Transition to Higher Math) Cardinality of Sets Fall 2014 3 / 15 Sets with Equal Cardinality Consider the following: This definition does not involve the number of elements in the sets. It works equally well for finite and infinite sets. Any bijection between the sets is sufficient. MAT231 (Transition to Higher Math) Cardinality of Sets Fall 2014 4 / 15 The set Z contains all the numbers in N as well as numbers not in N. So maybe Z is larger than N... On the other hand, both sets are infinite, so maybe Z is the same size as N... This is just the sort of ambiguity we want to avoid, so we appeal to the definition of \same cardinality." The answer to our question boils down to \Can we find a bijection between N and Z?" Does jNj = jZj? True or false: Z is larger than N. -

I Want to Start My Story in Germany, in 1877, with a Mathematician Named Georg Cantor

LISTENING - Ron Eglash is talking about his project http://www.ted.com/talks/ 1) Do you understand these words? iteration mission scale altar mound recursion crinkle 2) Listen and answer the questions. 1. What did Georg Cantor discover? What were the consequences for him? 2. What did von Koch do? 3. What did Benoit Mandelbrot realize? 4. Why should we look at our hand? 5. What did Ron get a scholarship for? 6. In what situation did Ron use the phrase “I am a mathematician and I would like to stand on your roof.” ? 7. What is special about the royal palace? 8. What do the rings in a village in southern Zambia represent? 3)Listen for the second time and decide whether the statements are true or false. 1. Cantor realized that he had a set whose number of elements was equal to infinity. 2. When he was released from a hospital, he lost his faith in God. 3. We can use whatever seed shape we like to start with. 4. Mathematicians of the 19th century did not understand the concept of iteration and infinity. 5. Ron mentions lungs, kidney, ferns, and acacia trees to demonstrate fractals in nature. 6. The chief was very surprised when Ron wanted to see his village. 7. Termites do not create conscious fractals when building their mounds. 8. The tiny village inside the larger village is for very old people. I want to start my story in Germany, in 1877, with a mathematician named Georg Cantor. And Cantor decided he was going to take a line and erase the middle third of the line, and take those two resulting lines and bring them back into the same process, a recursive process. -

STRUCTURE ENUMERATION and SAMPLING Chemical Structure Enumeration and Sampling Have Been Studied by Mathematicians, Computer

STRUCTURE ENUMERATION AND SAMPLING MARKUS MERINGER To appear in Handbook of Chemoinformatics Algorithms Chemical structure enumeration and sampling have been studied by 5 mathematicians, computer scientists and chemists for quite a long time. Given a molecular formula plus, optionally, a list of structural con- straints, the typical questions are: (1) How many isomers exist? (2) Which are they? And, especially if (2) cannot be answered completely: (3) How to get a sample? 10 In this chapter we describe algorithms for solving these problems. The techniques are based on the representation of chemical compounds as molecular graphs (see Chapter 2), i.e. they are mainly applied to constitutional isomers. The major problem is that in silico molecular graphs have to be represented as labeled structures, while in chemical 15 compounds, the atoms are not labeled. The mathematical concept for approaching this problem is to consider orbits of labeled molecular graphs under the operation of the symmetric group. We have to solve the so–called isomorphism problem. According to our introductory questions, we distinguish several dis- 20 ciplines: counting, enumerating and sampling isomers. While counting only delivers the number of isomers, the remaining disciplines refer to constructive methods. Enumeration typically encompasses exhaustive and non–redundant methods, while sampling typically lacks these char- acteristics. However, sampling methods are sometimes better suited to 25 solve real–world problems. There is a wide range of applications where counting, enumeration and sampling techniques are helpful or even essential. Some of these applications are closely linked to other chapters of this book. Counting techniques deliver pure chemical information, they can help to estimate 30 or even determine sizes of chemical databases or compound libraries obtained from combinatorial chemistry. -

Georg Cantor English Version

GEORG CANTOR (March 3, 1845 – January 6, 1918) by HEINZ KLAUS STRICK, Germany There is hardly another mathematician whose reputation among his contemporary colleagues reflected such a wide disparity of opinion: for some, GEORG FERDINAND LUDWIG PHILIPP CANTOR was a corruptor of youth (KRONECKER), while for others, he was an exceptionally gifted mathematical researcher (DAVID HILBERT 1925: Let no one be allowed to drive us from the paradise that CANTOR created for us.) GEORG CANTOR’s father was a successful merchant and stockbroker in St. Petersburg, where he lived with his family, which included six children, in the large German colony until he was forced by ill health to move to the milder climate of Germany. In Russia, GEORG was instructed by private tutors. He then attended secondary schools in Wiesbaden and Darmstadt. After he had completed his schooling with excellent grades, particularly in mathematics, his father acceded to his son’s request to pursue mathematical studies in Zurich. GEORG CANTOR could equally well have chosen a career as a violinist, in which case he would have continued the tradition of his two grandmothers, both of whom were active as respected professional musicians in St. Petersburg. When in 1863 his father died, CANTOR transferred to Berlin, where he attended lectures by KARL WEIERSTRASS, ERNST EDUARD KUMMER, and LEOPOLD KRONECKER. On completing his doctorate in 1867 with a dissertation on a topic in number theory, CANTOR did not obtain a permanent academic position. He taught for a while at a girls’ school and at an institution for training teachers, all the while working on his habilitation thesis, which led to a teaching position at the university in Halle. -

Methods of Enumeration of Microorganisms

Microbiology BIOL 275 ENUMERATION OF MICROORGANISMS I. OBJECTIVES • To learn the different techniques used to count the number of microorganisms in a sample. • To be able to differentiate between different enumeration techniques and learn when each should be used. • To have more practice in serial dilutions and calculations. II. INTRODUCTION For unicellular microorganisms, such as bacteria, the reproduction of the cell reproduces the entire organism. Therefore, microbial growth is essentially synonymous with microbial reproduction. To determine rates of microbial growth and death, it is necessary to enumerate microorganisms, that is, to determine their numbers. It is also often essential to determine the number of microorganisms in a given sample. For example, the ability to determine the safety of many foods and drugs depends on knowing the levels of microorganisms in those products. A variety of methods has been developed for the enumeration of microbes. These methods measure cell numbers, cell mass, or cell constituents that are proportional to cell number. The four general approaches used for estimating the sizes of microbial populations are direct and indirect counts of cells and direct and indirect measurements of microbial biomass. Each method will be described in more detail below. 1. Direct Count of Cells Cells are counted directly under the microscope or by an electronic particle counter. Two of the most common procedures used in microbiology are discussed below. Direct Count Using a Counting Chamber Direct microscopic counts are performed by spreading a measured volume of sample over a known area of a slide, counting representative microscopic fields, and relating the averages back to the appropriate volume-area factors. -

Unit 1: Counting and Cardinality Goal: Students Will Learn Number Names, the Counting Sequence, How to Count to Tell the Number of Objects, and How to Compare Numbers

Kindergarten – Trimester 1: Aug – Oct (11 weeks) Unit 1: Counting and Cardinality Goal: Students will learn number names, the counting sequence, how to count to tell the number of objects, and how to compare numbers. Students will represent and use whole numbers, initially with a set of objects. Students will learn to describe shapes and space. Structures to Support CA Content Standards/CGI/Problem Solving: Real World Math, Problem Analysis “Think Time”, Partner Collaboration, Productive Struggle, Whole Group Student Share Youcubed Week of Inspirational Math https://www.youcubed.org/week-inspirational-math/ Common Unit Tasks and Critical Areas of Instruction Core Curriculum Work Assessments/Proficiency Scale(s): Critical Concepts: Focus Areas (use these activities most of the time): Trimester 1 Tasks & Assessments: ● Cognitively Guided Counting and Cardinality: -Counting Collections Instruction ● MyMath Ch 1: Numbers 0 to 5 -Describe, Draw, Describe ● Counting Collections ● MyMath Ch 2: Numbers to 10 -Card games ● Word Problems (Separate – ● MyMath Ch 3: Numbers Beyond 10 -CGI Assessment (do in BOY, MOY, and EOY Result Unknown, Join – ● Counting Collections: What is it? to gauge student growth) Result Unknown, Partitive ● Questions for Counting Collections ● CGI Assessment Launch Script Division) ● Number Talks/Math Warm Ups (Ordinal numbers, compare ● CGI Kinder intro Assessment A ● Name, recognize, count, and numbers) ● K-1 CGI assess codebook write numbers 0 to 20 Operations/Algebraic Thinking: ● Compare numbers to 10 ● Word Problems -

Cantor and Continuity

Cantor and Continuity Akihiro Kanamori May 1, 2018 Georg Cantor (1845-1919), with his seminal work on sets and number, brought forth a new field of inquiry, set theory, and ushered in a way of proceeding in mathematics, one at base infinitary, topological, and combinatorial. While this was the thrust, his work at the beginning was embedded in issues and concerns of real analysis and contributed fundamentally to its 19th Century rigorization, a development turning on limits and continuity. And a continuing engagement with limits and continuity would be very much part of Cantor's mathematical journey, even as dramatically new conceptualizations emerged. Evolutionary accounts of Cantor's work mostly underscore his progressive ascent through set- theoretic constructs to transfinite number, this as the storied beginnings of set theory. In this article, we consider Cantor's work with a steady focus on con- tinuity, putting it first into the context of rigorization and then pursuing the increasingly set-theoretic constructs leading to its further elucidations. Beyond providing a narrative through the historical record about Cantor's progress, we will bring out three aspectual motifs bearing on the history and na- ture of mathematics. First, with Cantor the first mathematician to be engaged with limits and continuity through progressive activity over many years, one can see how incipiently metaphysical conceptualizations can become systemati- cally transmuted through mathematical formulations and results so that one can chart progress on the understanding of concepts. Second, with counterweight put on Cantor's early career, one can see the drive of mathematical necessity pressing through Cantor's work toward extensional mathematics, the increasing objectification of concepts compelled, and compelled only by, his mathematical investigation of aspects of continuity and culminating in the transfinite numbers and set theory.