Abundance of Grassland Sparrows on Reclaimed Surface Mines in Western Pennsylvania1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comprehensive Multilocus Assessment of Sparrow (Aves: Passerellidae) Relationships ⇑ John Klicka A, , F

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 77 (2014) 177–182 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Short Communication A comprehensive multilocus assessment of sparrow (Aves: Passerellidae) relationships ⇑ John Klicka a, , F. Keith Barker b,c, Kevin J. Burns d, Scott M. Lanyon b, Irby J. Lovette e, Jaime A. Chaves f,g, Robert W. Bryson Jr. a a Department of Biology and Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture, University of Washington, Box 353010, Seattle, WA 98195-3010, USA b Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Behavior, University of Minnesota, 100 Ecology Building, 1987 Upper Buford Circle, St. Paul, MN 55108, USA c Bell Museum of Natural History, University of Minnesota, 100 Ecology Building, 1987 Upper Buford Circle, St. Paul, MN 55108, USA d Department of Biology, San Diego State University, San Diego, CA 92182, USA e Fuller Evolutionary Biology Program, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Cornell University, 159 Sapsucker Woods Road, Ithaca, NY 14950, USA f Department of Biology, University of Miami, 1301 Memorial Drive, Coral Gables, FL 33146, USA g Universidad San Francisco de Quito, USFQ, Colegio de Ciencias Biológicas y Ambientales, y Extensión Galápagos, Campus Cumbayá, Casilla Postal 17-1200-841, Quito, Ecuador article info abstract Article history: The New World sparrows (Emberizidae) are among the best known of songbird groups and have long- Received 6 November 2013 been recognized as one of the prominent components of the New World nine-primaried oscine assem- Revised 16 April 2014 blage. Despite receiving much attention from taxonomists over the years, and only recently using molec- Accepted 21 April 2014 ular methods, was a ‘‘core’’ sparrow clade established allowing the reconstruction of a phylogenetic Available online 30 April 2014 hypothesis that includes the full sampling of sparrow species diversity. -

Ultimate Bolivia Tour Report 2019

Titicaca Flightless Grebe. Swimming in what exactly? Not the reed-fringed azure lake, that’s for sure (Eustace Barnes) BOLIVIA 8 – 29 SEPTEMBER / 4 OCTOBER 2019 LEADER: EUSTACE BARNES Bolivia, indeed, THE land of parrots as no other, but Cotingas as well and an astonishing variety of those much-loved subfusc and generally elusive denizens of complex uneven surfaces. Over 700 on this tour now! 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Ultimate Bolivia 2019 www.birdquest-tours.com Blue-throated Macaws hoping we would clear off and leave them alone (Eustace Barnes) Hopefully, now we hear of colourful endemic macaws, raucous prolific birdlife and innumerable elusive endemic denizens of verdant bromeliad festooned cloud-forests, vast expanses of rainforest, endless marshlands and Chaco woodlands, each ringing to the chorus of a diverse endemic avifauna instead of bleak, freezing landscapes occupied by impoverished unhappy peasants. 2 BirdQuest Tour Report: Ultimate Bolivia 2019 www.birdquest-tours.com That is the flowery prose, but Bolivia IS that great destination. The tour is no longer a series of endless dusty journeys punctuated with miserable truck-stop hotels where you are presented with greasy deep-fried chicken and a sticky pile of glutinous rice every day. The roads are generally good, the hotels are either good or at least characterful (in a good way) and the food rather better than you might find in the UK. The latter perhaps not saying very much. Palkachupe Cotinga in the early morning light brooding young near Apolo (Eustace Barnes). That said, Bolivia has work to do too, as its association with that hapless loser, Che Guevara, corruption, dust and drug smuggling still leaves the country struggling to sell itself. -

Henslow's Sparrow

Table of Contents I. Introduction………………………………………………………… 1 II. Species Account……………………………………………………. 1 A. Taxonomy Description…………………………………………. 1 1. Original Description…………………………………….. 1 2. Taxonomic Description…………………………………. 3 B. Historical and Current Distribution……………………………... 3 1. Description of Habitats and Locations of Occurrence….. 3 2. Known Collection Sites………………………………… 5 3. Associated Species and Communities………………...... 5 C. Population Sizes and Abundance………………………………. 7 D. Reproduction…………………………………………………… 8 E. Food and Feeding Requirements……………………………...... 8 F. Other Pertinent Information and Summary…………………...... 9 III. Ownership of Properties…………………………………………… 9 IV. Potential Threats…………………………………………………… 10 V. Protective Laws…………………………………………………...... 12 A. Federal………………………………………………………...... 12 B. State…………………………………………………………...... 12 VI. Recovery………………………………………………………….... 12 A. Objectives………………………………………………………. 12 B. Recovery Criteria……………………………………………..... 12 VII. Narrative Outline…………………………………………………... 13 1. Additional Species Information Needs…………………………. 13 2. Management Activities for Maintaining Species Populations and for Species Recovery………………………………………....... 14 VIII. Costs of Recovery Plan Implementation…………………………… 15 Table 1 Henslow’s sparrow densities for sites of occurrence………………. 18 Figure 1……………………………………………………………………………..... 20 Literature Cited………………………………………………………………………. 21 i Acknowledgements We would like to thank all of the individuals who assisted with or provided information for the completion of this plan. Most -

An Update of Wallacels Zoogeographic Regions of the World

REPORTS To examine the temporal profile of ChC produc- specification of a distinct, and probably the last, 3. G. A. Ascoli et al., Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 557 (2008). tion and their correlation to laminar deployment, cohort in this lineage—the ChCs. 4. J. Szentágothai, M. A. Arbib, Neurosci. Res. Program Bull. 12, 305 (1974). we injected a single pulse of BrdU into pregnant A recent study demonstrated that progeni- CreER 5. P. Somogyi, Brain Res. 136, 345 (1977). Nkx2.1 ;Ai9 females at successive days be- tors below the ventral wall of the lateral ventricle 6. L. Sussel, O. Marin, S. Kimura, J. L. Rubenstein, tween E15 and P1 to label mitotic progenitors, (i.e., VGZ) of human infants give rise to a medial Development 126, 3359 (1999). each paired with a pulse of tamoxifen at E17 to migratory stream destined to the ventral mPFC 7. S. J. Butt et al., Neuron 59, 722 (2008). + 18 8. H. Taniguchi et al., Neuron 71, 995 (2011). label NKX2.1 cells (Fig. 3A). We first quanti- ( ). Despite species differences in the develop- 9. L. Madisen et al., Nat. Neurosci. 13, 133 (2010). fied the fraction of L2 ChCs (identified by mor- mental timing of corticogenesis, this study and 10. J. Szabadics et al., Science 311, 233 (2006). + phology) in mPFC that were also BrdU+. Although our findings raise the possibility that the NKX2.1 11. A. Woodruff, Q. Xu, S. A. Anderson, R. Yuste, Front. there was ChC production by E15, consistent progenitors in VGZ and their extended neurogenesis Neural Circuits 3, 15 (2009). -

Southeast Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna, Oct-Nov 2016

Tropical Birding Trip Report Southeast Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna, Oct-Nov 2016 SOUTHEAST BRAZIL: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna October 20th – November 8th, 2016 TOUR LEADER: Nick Athanas Report and photos by Nick Athanas Helmeted Woodpecker - one of our most memorable sightings of the tour It had been a couple of years since I last guided this tour, and I had forgotten how much fun it could be. We covered a lot of ground and visited a great series of parks, lodges, and reserves, racking up a respectable group list of 459 bird species seen as well as some nice mammals. There was a lot of rain in the area, but we had to consider ourselves fortunate that the rainiest days seemed to coincide with our long travel days, so it really didn’t cost us too much in the way of birds. My personal trip favorite sighting was our amazing and prolonged encounter with a rare Helmeted Woodpecker! Others of note included extreme close-ups of Spot-winged Wood-Quail, a surprise Sungrebe, multiple White-necked Hawks, Long-trained Nightjar, 31 species of antbirds, scope views of Variegated Antpitta, a point-blank Spotted Bamboowren, tons of colorful hummers and tanagers, TWO Maned Wolves at the same time, and Giant Anteater. This report is a bit light on text and a bit heavy of photos, mainly due to my insane schedule lately where I have hardly had any time at home, but all photos are from the tour. www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Tropical Birding Trip Report Southeast Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna, Oct-Nov 2016 The trip started in the city of Curitiba. -

South East Brazil, 18Th – 27Th January 2018, by Martin Wootton

South East Brazil 18th – 27th January 2018 Grey-winged Cotinga (AF), Pico da Caledonia – rare, range-restricted, difficult to see, Bird of the Trip Introduction This report covers a short trip to South East Brazil staying at Itororó Eco-lodge managed & owned by Rainer Dungs. Andy Foster of Serra Dos Tucanos guided the small group. Itinerary Thursday 18th January • Nightmare of a travel day with the flight leaving Manchester 30 mins late and then only able to land in Amsterdam at the second attempt due to high winds. Quick sprint (stagger!) across Schiphol airport to get onto the Rio flight which then parked on the tarmac for 2 hours due to the winds. Another roller-coaster ride across a turbulent North Atlantic and we finally arrived in Rio De Janeiro two hours late. Eventually managed to get the free shuttle to the Linx Hotel adjacent to airport Friday 19th January • Collected from the Linx by our very punctual driver (this was to be a theme) and 2.5hour transfer to Itororo Lodge through surprisingly light traffic. Birded the White Trail in the afternoon. Saturday 20th January • All day in Duas Barras & Sumidouro area. Luggage arrived. Sunday 21st January • All day at REGUA (Reserva Ecologica de Guapiacu) – wetlands and surrounding lowland forest. Andy was ill so guided by the very capable REGUA guide Adelei. Short visit late pm to Waldanoor Trail for Frilled Coquette & then return to lodge Monday 22nd January • All day around lodge – Blue Trail (am) & White Trail (pm) Tuesday 23rd January • Early start (& finish) at Pico da Caledonia. -

Henslow's Sparrow Habitat, Site Fidelity, and Reproduction in Missouri

EFFECTS OF MANAGEMENT PRACTICES ON GRASSLAND BIRDS: HENSLOW’S SPARROW Grasslands Ecosystem Initiative Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center U.S. Geological Survey Jamestown, North Dakota 58401 This report is one in a series of literature syntheses on North American grassland birds. The need for these reports was identified by the Prairie Pothole Joint Venture (PPJV), a part of the North American Waterfowl Management Plan. The PPJV recently adopted a new goal, to stabilize or increase populations of declining grassland- and wetland-associated wildlife species in the Prairie Pothole Region. To further that objective, it is essential to understand the habitat needs of birds other than waterfowl, and how management practices affect their habitats. The focus of these reports is on management of breeding habitat, particularly in the northern Great Plains. Suggested citation: Herkert, J. R. 1998 (revised 2002). Effects of management practices on grassland birds: Henslow’s Sparrow. Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center, Jamestown, ND. 17 pages. Species for which syntheses are available or are in preparation: American Bittern Grasshopper Sparrow Mountain Plover Baird’s Sparrow Marbled Godwit Henslow’s Sparrow Long-billed Curlew Le Conte’s Sparrow Willet Nelson’s Sharp-tailed Sparrow Wilson’s Phalarope Vesper Sparrow Upland Sandpiper Savannah Sparrow Greater Prairie-Chicken Lark Sparrow Lesser Prairie-Chicken Field Sparrow Northern Harrier Clay-colored Sparrow Swainson’s Hawk Chestnut-collared Longspur Ferruginous Hawk McCown’s Longspur Short-eared Owl Dickcissel Burrowing Owl Lark Bunting Horned Lark Bobolink Sedge Wren Eastern Meadowlark Loggerhead Shrike Western Meadowlark Sprague’s Pipit Brown-headed Cowbird EFFECTS OF MANAGEMENT PRACTICES ON GRASSLAND BIRDS: HENSLOW’S SPARROW James R. -

The Function and Evolution of Egg Colour in Birds

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 2012 The function and evolution of egg colour in birds Daniel Hanley University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation Hanley, Daniel, "The function and evolution of egg colour in birds" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 382. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/382 This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. THE FUNCTION AND EVOLUTION OF EGG COLOURATION IN BIRDS by Daniel Hanley A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies through Biological Sciences in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Windsor Windsor, Ontario, Canada 2011 © Daniel Hanley THE FUNCTION AND EVOLUTION OF EGG COLOURATION IN BIRDS by Daniel Hanley APPROVED BY: __________________________________________________ Dr. D. Lahti, External Examiner Queens College __________________________________________________ Dr. -

Year-Round and Migratory Birds of the Flint Hills

Kansas State University Libraries New Prairie Press 2012 – The Prairie: Its Seasons and Rhythms Symphony in the Flint Hills Field Journal (Laurie J. Hamilton, Editor) Year-round and Migratory Birds of the Flint Hills William H. Busby Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sfh Recommended Citation Busby, William H. (2012). "Year-round and Migratory Birds of the Flint Hills," Symphony in the Flint Hills Field Journal. https://newprairiepress.org/sfh/2012/prairie/3 To order hard copies of the Field Journals, go to shop.symphonyintheflinthills.org. The Field Journals are made possible in part with funding from the Fred C. and Mary R. Koch Foundation. This is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences at New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Symphony in the Flint Hills Field Journal by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Year-round and Migratory Birds of the Flint Hills The Flint Hills support a wide diversity of birds with some 250 species having been recorded. They range in size from the Ruby-throated Hummingbird (3 grams) to the 10-kg Wild Turkey. Birds tend to specialize by habitat, and each habitat---be it tallgrass prairie, shrublands, riparian forest, cropland, or farmstead---supports its own assemblage of bird species. Grassland birds occupy the And spring, summer, fall and winter UPLAND SANDPIPER dominant habitat, the tallgrass prairie, seasons host a different set of birds. of the Flint Hills. Although the Flint While these grassland birds are well- Hills provide “home” to approximately adapted to the prairie environment, 60 species, each species prefers certain the Flint Hills and the tallgrass prairie site characteristics and seasons. -

Neotropical Notebooks Please Include During a Visit on 9 April 1994 (Pyle Et Al

COTINGA 1 Neotropical Notebook Neotropical Notebook These recent reports generally refer to new or Chiriqui, during fieldwork between 1987 and 1991, second country records, rediscoveries, notable representing a disjunct population from that of Mexico range extensions, and new localities for threat to north-western Costa Rica (Olson 1993). Red- ened or poorly known species. These have been throated Caracara Daptrius americanus has been collated from a variety of published and unpub rediscovered in western Panama, with several seen and lished sources, and therefore some records will be heard on 26 August 1993 around the indian village of unconfirmed. We urge that, if they have not al Teribe (Toucan 19[9]: 5). ready done so, contributors provide full details to the relevant national organisations. COLOMBIA Recent expeditions and increasing interest in this coun BELIZE try has produced a wealth of new information, including There are five new records for the country as follows: a 12 new country records. A Cambridge–RHBNC expedi light phase Pomarine Jaeger Stercorarius pomarinus tion to Serranía de Naquén, Amazonas, in July–August seen by the fisheries pier, Belize City, 1 May 1992; 1992 found 4 new country records as follows: Rusty several Fulvous Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna bicolor Tinamou Crypturellus brevirostris observed at an ant- seen at Cox Lagoon in November 1986, up to 20 at swarm at Caño Ima, 12 August; Brown-banded Crooked Tree in March 1988, and again on 3 May 1992; Puffbird Notharchus tricolor observed in riverside a Chuck-will’s Widow Caprimulgus carolinensis col trees between Mahimachi and Caño Colorado [no date]; lected at San Ignacio, Cayo District, 13 October 1991; and a male Guianan Gnatcatcher Polioptila guianensis Spectacled Foliage-gleaner Anabacerthia observed at close range in a mixed flock at Caño Rico, 2 variegaticeps recently recorded on an expedition to the August (Amazon 1992). -

The Relationship Between Bororo Indigenous and the Birds in the Brazilian Savannah

Available online at www.worldnewsnaturalsciences.com WNOFNS 31 (2020) 9-24 EISSN 2543-5426 The relationship between Bororo Indigenous and the birds in the Brazilian Savannah Fabio Rossano Dario Ethnobiological Researcher, Instituto de Pesquisas e Estudos da Vida Silvestre Rua Leonardo Mota, 66 - São Paulo-SP, ZIP 05586-090, Brazil E-mail address: [email protected] Phone: +5511981541925 ABSTRACT The objective of this study accomplished a knowledge survey of the Bororo indigenous on the birds of natural occurrence in their territory, Meruri village, who is located in the Mato Grosso State, Brazil, in the Savannah biome, and also the relationship of the indigenous with these birds. As the method for collect, the data were used open and semi-structured interviews. Twenty-two indigenous were interviewed, both genres and different ages. The interviewees mentioned 96 species of birds and they showed wide ecological knowledge regarding these birds. Such relationships are complex, being evidenced by a mythical interaction between the man and the elements of nature. These birds are important elements in the creation of stories, legends, in the Bororo ceremonies and arts. The oral transmission of knowledge occurs across generations. Keywords: birds, ethnobiology, ecology, indigenous, Bororo, Brazilian Savannah 1. INTRODUCTION Traditional ecological knowledge is a system of knowledge that reflects the adaptation of human populations to their environment. Ethnobiology is the scientific study of dynamic relationships among peoples, biota, and environments. As a multidisciplinary field, ethnobiology integrates archaeology, geography, systematics, population biology, ecology, cultural anthropology, ethnography, pharmacology, nutrition, conservation, and sustainable development [1]. The diversity of perspectives in ethnobiology allows us to examine complex, dynamic interactions between human and natural systems [2]. -

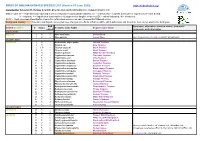

BIRDS of BOLIVIA UPDATED SPECIES LIST (Version 03 June 2020) Compiled By: Sebastian K

BIRDS OF BOLIVIA UPDATED SPECIES LIST (Version 03 June 2020) https://birdsofbolivia.org/ Compiled by: Sebastian K. Herzog, Scientific Director, Asociación Armonía ([email protected]) Status codes: R = residents known/expected to breed in Bolivia (includes partial migrants); (e) = endemic; NB = migrants not known or expected to breed in Bolivia; V = vagrants; H = hypothetical (observations not supported by tangible evidence); EX = extinct/extirpated; IN = introduced SACC = South American Classification Committee (http://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCBaseline.htm) Background shading = Scientific and English names that have changed since Birds of Bolivia (2016, 2019) publication and thus differ from names used in the field guide BoB Synonyms, alternative common names, taxonomic ORDER / FAMILY # Status Scientific name SACC English name SACC plate # comments, and other notes RHEIFORMES RHEIDAE 1 R 5 Rhea americana Greater Rhea 2 R 5 Rhea pennata Lesser Rhea Rhea tarapacensis , Puna Rhea (BirdLife International) TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE 3 R 1 Nothocercus nigrocapillus Hooded Tinamou 4 R 1 Tinamus tao Gray Tinamou 5 H, R 1 Tinamus osgoodi Black Tinamou 6 R 1 Tinamus major Great Tinamou 7 R 1 Tinamus guttatus White-throated Tinamou 8 R 1 Crypturellus cinereus Cinereous Tinamou 9 R 2 Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou 10 R 2 Crypturellus obsoletus Brown Tinamou 11 R 1 Crypturellus undulatus Undulated Tinamou 12 R 2 Crypturellus strigulosus Brazilian Tinamou 13 R 1 Crypturellus atrocapillus Black-capped Tinamou 14 R 2 Crypturellus variegatus