Chile: Global Astronomical Platform and Opportunity for Diplomacy,” Science & Diplomacy, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Overview and Status of the Giant Magellan Telescope Project

Invited Paper Overview and Status of the Giant Magellan Telescope Project Patrick J. McCarthy*,a,b, James Fansona, Rebecca Bernsteina,b, David Ashbyc, Bruce Bigelowa, Nune Boyadjiana, Antonin Boucheza, Eric Chauvina, Eduardo Donosoa, Jose Filgueiraa, Robert Goodricha, Frank Groarka, George Jacobya, Eric Pearcea aGMTO Corporation, 451 N. Halstead St., Suite 250, Pasadena, CA 91107, USA bCarnegie Observatories, 813 Santa Barbara St., Pasadena, CA 91101, USA cLarge Binocular Telescope Observatory, Tucson AZ ABSTRACT The Giant Magellan Telescope Project is in the construction phase. Production of the primary mirror segments is underway with four of the seven required 8.4m mirrors at various stages of completion and materials purchased for segments five and six. Development of the infrastructure at the GMT site at Las Campanas is nearing completion. Power, water and data connections sufficient to support the construction of the telescope and enclosure are in place and roads to the summit have been widened and graded to support transportation of large and heavy loads. Construction pads for the support buildings have been graded and the construction residence is being installed. A small number of issues need to be resolved before the final design of the telescope structure and enclosure can proceed and the GMT team is collecting the required inputs to the decision making process. Prototyping activities targeted at the active and adaptive optics systems are allowing us to finalize designs before large scale production of components begins. Our technically driven schedule calls for the telescope to be assembled on site in 2022 and to be ready to receive a subset of the primary and secondary mirror optics late in the year. -

1 Director's Message

1 Director’s Message Laura Ferrarese 3 Rocky Planet Engulfment Explains Stellar Odd Couple Carlos Saffe 7 Astronomers Feast on First Light From Gravitational Wave Event Peter Michaud 11 Science Highlights Peter Michaud 15 On the Horizon Gemini staff contributions 18 News for Users Gemini staff contributions ON THE COVER: GeminiFocus October 2017 Gemini South provided critical GeminiFocus is a quarterly publication observations of the first of the Gemini Observatory electromagnetic radiation from 670 N. A‘ohoku Place, Hilo, Hawai‘i 96720, USA a gravitational wave event. / Phone: (808) 974-2500 / Fax: (808) 974-2589 (See details starting on page 7.) Online viewing address: www.gemini.edu/geminifocus Managing Editor: Peter Michaud Associate Editor: Stephen James O’Meara Designer: Eve Furchgott/Blue Heron Multimedia Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation or the Gemini Partnership. ii GeminiFocus October 2017 Laura Ferrarese Director’s Message The Three Goals of a Year-long Vision Hello, Aloha, and Hola! I am delighted to address the Gemini community from my new role as the Observatory’s Interim Director. I will hold this position for the next year, while the search for a perma- nent Director moves forward. As I write this (beginning of September), I have been in Hilo, Hawai‘i, for almost two months, and it’s been an exciting time. I have enjoyed work- ing with the Gemini staff, whose drive, dedication, and talent were already well known to me from when I chaired the Observatory Oversight Council on behalf of the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA). -

Gemini North Telescope

Gemini North Telescope Image Credit: Gemini Observatory/AURA/Joy Pollard Gemini Observatory Legacy Image Gemini North Telescope Gemini Observatory Facts The Gemini Observatory is operated by the Association of Universities for The 8-meter Frederick C. Gillett Gemini North telescope is PRIMARY MIRRORS: Research in Astronomy, Inc., under a cooperative agreement with the located near the summit of Hawaii’s Maunakea — a long Diameter: 8.1 meters; 26.57 feet; 318.84 inches National Science Foundation on behalf Mass: 22.22 metric tonnes; 24.5 U.S. tons of the Gemini Partnership. dormant volcano rising 4,205 meters into the dry, stable air Composition: Corning Ultra-Low Expansion (ULE) Glass of the North Pacific. Gemini North was designed and built, Surface Accuracy: 15.6 nm RMS (between 1/1000 - 1/10,000 in part, to provide the best image quality possible from the thickness of human hair) ground for telescopes of its size. TELESCOPE STRUCTURES: United States Four significant features help the telescope achieve this Height: 21.7 meters; 71.2 feet; 7 stories (from “Observing Floor”) goal: (1) An ~20-centimeter-thin primary mirror on a bed of Weight: 380 metric tonnes; 419 U.S. tons Optomechanical Design: Cassegrain ; Alt-azimuth 120 hydraulic actuators; (2) a 1-meter-diameter secondary DOMES: Canada mirror capable of rapid tip-tilt corrective motions; (3) vents on the cylindrical walls to provide a smooth flow of air Height: 46 meters; 151 feet; 15 stories (from ground) above the primary mirror, and to regulate the temperature Weight: 780 metric tonnes; 860 U.S. tons (moving mass) Rotation: 360 degrees in 2 minutes of the air above the mirror to match the outside Thermal Vents: 10 meters; 32.8 feet (width – fully open) temperature; and (4) an adaptive optics system which Brazil GEOGRAPHICAL DATA: can correct for image blurring caused by atmospheric Elevation: Gemini North: 4,214 meters; 13,824 feet turbulence. -

Noirlab Visual Identity V.1.0 — Noirlab Brand Manual “A Logo Is a Flag, a Signature, an Escutcheon, a Street Sign

NOIRLab Visual Identity v.1.0 — NOIRLab Brand Manual “A logo is a flag, a signature, an escutcheon, a street sign. A logo identifies. A logo is rarely a description of a business. A logo derives meaning from the quality of the thing it symbolizes, not the other way around. A logo is less important than the product it signifies; what it represents is more important than what it looks like. The subject matter of a logo can be almost anything.” Paul Rand VI 1.0 ii Table of Contents NOIRLab Visual Identity v.1.0 i » — NOIRLab Brand Manual i Introduction — about this manual 1 ● About NOIRLab 1 ● NOIRLab Design brief 3 » Logo 3 ● General branding principles 4 The NOIRLab Logo 5 ● NOIRLab logo variations 7 » Versions for colored backgrounds 7 » Appropriate and Inappropriate Uses 8 » Widescreen version (for special applications) 9 » Clear Space 9 » NSF and NOIRLab 9 NOIRLab Typeface 10 ● Quatro — Headlines, Subheads, & Callouts 10 ● Source Sans Pro — for sans serif body text 10 ● Freight — for serif body text 10 ● Fallback typeface: Arial — (sans serif) 10 ● Times New Roman — (serif) 10 Color Usage 11 ● Accent Colors 11 Additional Brand Elements 12 ● Watermark elements 13 ● Program Iconography 13 Applications of the Visual Identity 14 ● Letterhead 14 ● Presentation slides 15 ● Poster Templates 15 ● Social Media Posts and Events 16 ● Employee Access Badges 16 ● Conference Nametags 16 ● Office Door Signs 17 ● Controlled document template 17 ● Credit block for CAD drawings 17 Acknowledgments and Affiliations 18 ● Acknowledgments in scientific papers 18 ● Affiliations on conference badges, email signatures etc. 18 iii 2021.06.24 ● Suggested Email signatures 18 ● NOIRLab Scientific and Technical Staff Affiliations 19 ● Image and video Credits 19 ● Branding issues in press releases and other texts 19 ● Business Cards 20 Program logos 21 ● NOIRLab Program Logos 21 ● Cerro Tololo 22 ● Kitt Peak 22 ● Community Science and Data Center 23 ● The Gemini Observatory 23 ● The Vera C. -

Experimental Facilities in Latin America

CLASHEP 2019, Villa General Belgrano, Córdoba, Argentina Experimental Facilities in Latin America Claudio O. Dib Universidad Técnica Federico Santa María, Valparaíso, Chile 7 to 5 Content: • Brief introduction to Particle Physics experiments. • Accelerator Facilities in L.A. • Astronomical Observatories in L.A. (current and future) - VLT, ALMA, DSA3, DES, LSST, GMT, ELT, LLAMA. • Current Astroparticle Facilities in L.A. - Auger - Parenthesis on Cosmic Rays and Extensive Air Showers. - LAGO, HAWC • Future Astroparticle Facilities in L.A. - CTA, ALPACA, LATTES, SGSO, ANDES • Summary 6 to 5 Particle Physics experiments: - Table top experiments E. Rutherford’s lab., Cambridge U. - Cosmic ray detection (Astroparticle Physics) - Accelerators and colliders: (cyclotrons, synchrotrons, linacs; fixed target collisions, colliding beams) 5 to 5 Past table-top experiments 1895: J.J Thomson -> electron J.J. Thomson. Credit: Cambridge U., Cavendish Lab. 1911: E. Rutherford -> nucleus & proton 1932: J. Chadwick -> neutron 4 to 5 J.A. Ratcliffe & E. Rutherford, Cavendish Lab. Cosmic ray experiments • Cosmic rays: radiation that comes from outer space. • Discovered in 1912 by Victor Hess: – Went up a Balloon up to 5300 m: Radiation is higher further above. • Named cosmic rays by R. A. Millikan. Victor F. Hess preparing the baloon flight Cosmic rays are actually… particles! (mainly protons & heavier nuclei) 3 to 5 Robert A. Millikan. Caltech archives. Cosmic ray experiments 1932: C. Anderson discovers the positron. 1947: C. Powell, G. Occhialini, C. Lattes -

The Giant Magellan Telescope. Status

The Giant Magellan Telescope. Status By Dr. Mauricio Pilleux Head of Administration (Chile) GMTO Corporation [email protected] April 17, 2019 Observatories in Chile: The beginnings … a successful experiment Cerro Tololo Interamerican Observatory AURA, 1962 Magellan telescopes, 2000 Las Campanas Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1968 La Silla ESO, 1969 2 Observatories in Chile: “Second stage” Very Large Telescope (VLT) Cerro Paranal, ESO, 1999 Gemini South Cerro Pachón, 2002 (AURA) ALMA NRAO-ESO-NAOJ, 2013 3 Observatories in Chile: “Stage 3.0” – big, big, big Giant Magellan Telescope (GMT) Cerro Las Campanas, 2023 (GMTO Corporation) European- Extremely Large Telescope (EELT) Cerro Armazones, 2026 (ESO) Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST) Cerro Pachón, 2022 (NSF/AURA-DOE/SLAC) 4 What next? Size (physical) GMT TMT EELT LSST Main Author – Presentation Title Observatories in Chile: Where? ALMA CCAT* Nanten 2 ASTE Paranal Vista ACT 2 3 E-ELT* TAO* Apex CTA* Las Campanas GMT* Polar Bear Simons Obs. La Silla 1 Tololo SOAR Gemini LSST* 6 Giant Magellan Telescope (GMT): Will be the largest in the world in 2022 25 meters in diameter “Price”: US$1340 million First light: 2023 Enclosure is 62 m high Groundbreaking research in: . Exoplanets and their atmospheres . Dark matter . Distant objects . Unknown unknowns 7 Just how tall is the GMT? 46 meters 8 Giant Magellan Telescope (GMT): The world’s largest optical telescope Korea Sao Paulo, Brazil Texas A&M Arizona New partners are welcome! Main Author – Presentation Title 9 Central mirror casting -

Precision Optics Manufacturing and Control for Next-Generation Large

Nanomanufacturing and Metrology https://doi.org/10.1007/s41871-019-00038-2 REVIEW PAPERS Precision Optics Manufacturing and Control for Next‑Generation Large Telescopes Logan R. Graves1 · Greg A. Smith1 · Dániel Apai2,3 · Dae Wook Kim1,2 Received: 2 December 2018 / Revised: 4 February 2019 / Accepted: 7 February 2019 © International Society for Nanomanufacturing and Tianjin University and Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. 2019 Abstract Next-generation astronomical telescopes will ofer unprecedented observational and scientifc capabilities to look deeper into the heavens, observe closer in time to the epoch of the Big Bang, and resolve fner details of phenomena throughout the universe. The science case for this next generation of observatories is clear, with science goals such as the discovery and exploration of extrasolar planets, exploration of dark matter and dark energy, the formation and evolution of planets, stars, galaxies, and detailed studies of the Sun. Enabling breakthrough astronomical goals requires novel and cutting-edge design choices at all stages of telescope manufacturing. In this paper, we discuss the integrated design and manufacturing of the next-generation large telescopes, from the optical design to enclosures required for optimal performance. Keywords Metrology · Fabrication · Design · Telescope · Optics · Precision 1 Introduction Expanding View of the Universe—Science with the Euro- pean Extremely Large Telescope [2]. To provide these scien- Astronomers studying new phenomena and testing increas- tifc capacities and to advance instrumentation capabilities, ingly detailed models of the universe require ever more pow- the next generation of telescopes (NGT) must provide higher erful instruments to complete their goals and collect photons spatial resolutions, larger light-collecting areas, and more which have traversed immense distances and time, some- sensitive instrumentation. -

NOAO NEWSLETTER from the Office of the Director

Director’s Corner NOAO NEWSLETTER From the Office of the Director .......................................................................................................................................2 ISSUE 118 | OCTOBER 2018 Science Highlights Looking Ahead to Looking Back in Time with DESI ....................................................................................................3 The Dark Energy Survey: The Journey So Far and the Path Forward ......................................................................5 Managing Editor A Reconnaissance of RECONS .......................................................................................................................................8 Sharon Hunt Discovering 12 New Moons Around Jupiter .................................................................................................................9 NOAO Director’s Office Community Science & Data David Silva “More Is Different” in Data-Driven Astronomy ..........................................................................................................11 Data Lab 2.0 Is Bigger and Better ...............................................................................................................................12 Science Highlights The US Extremely Large Telescope Program .............................................................................................................13 Tod R. Lauer “Science and Evolution of Gemini Observatory” Conference ...............................................................................14 -

Exoplanet Community Report

JPL Publication 09‐3 Exoplanet Community Report Edited by: P. R. Lawson, W. A. Traub and S. C. Unwin National Aeronautics and Space Administration Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology Pasadena, California March 2009 The work described in this publication was performed at a number of organizations, including the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, under a contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). Publication was provided by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Compiling and publication support was provided by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology under a contract with NASA. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not constitute or imply its endorsement by the United States Government, or the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology. © 2009. All rights reserved. The exoplanet community’s top priority is that a line of probeclass missions for exoplanets be established, leading to a flagship mission at the earliest opportunity. iii Contents 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 INTRODUCTION...............................................................................................................................................1 1.2 EXOPLANET FORUM 2008: THE PROCESS OF CONSENSUS BEGINS.....................................................2 -

The Galactic Center

Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union IAU Symposium No. 303 IAU Symposium IAU Symposium 30 September – 4 October 2013 IAU Symposium 303 highlights the latest Galactic Center research by scientists from around the world. Topics vary from theory 303 Santa Fe, NM, USA through observations, from stars and stellar orbits through nearby black holes and explosive events, to the building blocks and transport of energy in galaxies similar to our own Milky Way. Highlights presented include: high-resolution, multi-wavelength 30 September – 303 30 September – 4 October 2013 The Galactic Center: large-scale surveys of molecular gas in the central molecular and 4 October 2013 The Galactic Center: dust zones of our Galaxy; studies of stellar populations and stellar Santa Fe, NM, USA orbits around the supermassive black hole Sgr A*; presentations of Santa Fe, NM, USA Feeding and Feedback theoretical models to explain the dusty S-cluster object (DSO) G2, Feeding and Feedback in as well as the general accretion and jet formation in the vicinity of Sgr A*; and discussions of large-scale γ -ray emission in the context in a Normal Galactic of energetic activity and magnetic fi elds in the Galactic Center. The volume concludes by looking ahead to future observing a Normal Galactic Nucleus Nucleus opportunities across the electromagnetic spectrum at very high resolution. Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union Editor in Chief: Prof. Thierry Montmerle This series contains the proceedings of major scientifi c meetings held by the International Astronomical Union. Each volume contains a series of articles on a topic of current interest in astronomy, giving a timely overview of research in the fi eld. -

Comet ISON Hurtles Toward an Uncertain Destiny with the Sun

3 Director’s Message Markus Kissler-Patig 6 Featured Science: Dynamical Masses of Galaxy Clusters Discovered with the Sunyaev-Zel’dovich Effect Cristóbal Sifón, Felipe Menanteau, John P. Hughes, and L. Felipe Barrientos, for the ACT collaboration 11 Science Highlights Nancy A. Levenson 14 Cover Story: GeMS Embarks on the Universe Benoit Neichel and Rodrigo Carrasco 19 Instrumentation Development Updates Percy Gomez, Stephen Goodsell, Fredrik Rantakyro, and Eric Tollestrup 23 Operations Corner Andy Adamson 26 Featured Press Release: Comet ISON Hurtles Toward an Uncertain Destiny with the Sun On the Cover: GeminiFocus July 2013 The montage on GeminiFocus is a quarterly publication of Gemini Observatory this issue’s cover highlights several of 670 N. A‘ohoku Place, Hilo, Hawai‘i 96720 USA the spectacular images Phone: (808) 974-2500 Fax: (808) 974-2589 gathered as part of Online viewing address: the System Verification www.gemini.edu/geminifocus of the Gemini Multi- Managing Editor: Peter Michaud conjugate adaptive Science Editor: Nancy A. Levenson optics System (GeMS). Associate Editor: Stephen James O’Meara See the article starting on page 14 Designer: Eve Furchgott / Blue Heron Multimedia to learn more about this system and the cutting-edge science it Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. is performing — right out of the starting gate! 2 GeminiFocus July2013 Markus Kissler-Patig Director’s Message 2013: A Year of Milestones, Change, and Accomplishments We’ve seen quite a few changes at Gemini since the start of 2013. -

Auxiliary Telescopes Control Software

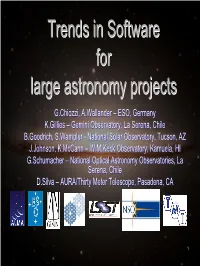

TrendsTrends inin SoftwareSoftware forfor largelarge astronomyastronomy projectsprojects G.Chiozzi, A.Wallander – ESO, Germany K.Gillies – Gemini Observatory, La Serena, Chile B.Goodrich, S.Wampler - National Solar Observatory, Tucson, AZ J.Johnson, K.McCann – W.M.Keck Observatory, Kamuela, HI G.Schumacher – National Optical Astronomy Observatories, La Serena, Chile D.Silva – AURA/Thirty Meter Telescope, Pasadena, CA 1 AspectsAspects analyzedanalyzed z TimelineTimeline z ChallengesChallenges z ArchitectureArchitecture z FrameworksFrameworks z DevelopmentDevelopment methodologiesmethodologies z TechnologicalTechnological implementationimplementation z HWHW platformsplatforms z OperatingOperating systemssystems z ProgrammingProgramming languageslanguages z User Interfaces. User Interfaces. 2 Keck TimelineTimeline VLT/VLTI 1990 Gemini N/S 1995 2000 LSST 2005 ALMA 2010 ATST 2015 TMT 2020 E-ELT 3 ChallengesChallenges ofof newnew projectsprojects z SynchronizedSynchronized multiplemultiple distributeddistributed controlcontrol loopsloops (wave(wave frontfront control)control) z MultiMulti--levellevel offoff--loadingloading schemesschemes z FaultFault detection,detection, isolationisolation andand recoveryrecovery (E(E--ELTELT M1:M1: 10001000 segmentssegments withwith actuatorsactuators andand sensors)sensors) z OperationalOperational efficiencyefficiency (TMT(TMT requirement:requirement: onon targettarget inin <5<5 minutes).minutes). 4 ArchitectureArchitecture z All major facilities in operation: three-tier architecture z High-level coordination