Guide to Sustainable Mountain Trails

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1922 Elizabeth T

co.rYRIG HT, 192' The Moootainetro !scot1oror,d The MOUNTAINEER VOLUME FIFTEEN Number One D EC E M BER 15, 1 9 2 2 ffiount Adams, ffiount St. Helens and the (!oat Rocks I ncoq)Ora,tecl 1913 Organized 190!i EDITORlAL ST AitF 1922 Elizabeth T. Kirk,vood, Eclttor Margaret W. Hazard, Associate Editor· Fairman B. L�e, Publication Manager Arthur L. Loveless Effie L. Chapman Subsc1·iption Price. $2.00 per year. Annual ·(onl�') Se,·ent�·-Five Cents. Published by The Mountaineers lncorJ,orated Seattle, Washington Enlerecl as second-class matter December 15, 19t0. at the Post Office . at . eattle, "\Yash., under the .-\0t of March 3. 1879. .... I MOUNT ADAMS lllobcl Furrs AND REFLEC'rION POOL .. <§rtttings from Aristibes (. Jhoutribes Author of "ll3ith the <6obs on lltount ®l!!mµus" �. • � J� �·,,. ., .. e,..:,L....._d.L.. F_,,,.... cL.. ��-_, _..__ f.. pt",- 1-� r�._ '-';a_ ..ll.-�· t'� 1- tt.. �ti.. ..._.._....L- -.L.--e-- a';. ��c..L. 41- �. C4v(, � � �·,,-- �JL.,�f w/U. J/,--«---fi:( -A- -tr·�� �, : 'JJ! -, Y .,..._, e� .,...,____,� � � t-..__., ,..._ -u..,·,- .,..,_, ;-:.. � --r J /-e,-i L,J i-.,( '"'; 1..........,.- e..r- ,';z__ /-t.-.--,r� ;.,-.,.....__ � � ..-...,.,-<. ,.,.f--· :tL. ��- ''F.....- ,',L � .,.__ � 'f- f-� --"- ��7 � �. � �;')'... f ><- -a.c__ c/ � r v-f'.fl,'7'71.. I /!,,-e..-,K-// ,l...,"4/YL... t:l,._ c.J.� J..,_-...A 'f ',y-r/� �- lL.. ��•-/IC,/ ,V l j I '/ ;· , CONTENTS i Page Greetings .......................................................................tlristicles }!}, Phoiitricles ........ r The Mount Adams, Mount St. Helens, and the Goat Rocks Outing .......................................... B1/.ith Page Bennett 9 1 Selected References from Preceding Mount Adams and Mount St. -

Kaiser Permanente CORE Provider List

Core Plans Provider Directory Table of Contents Personal Physicians 1 (1926 Total) Specialty Care 27 (7979 Total) Behavioral Health Services 170 (2922 Total) Urgent Care 225 (85 Total) Hospitals 228 (69 Total) Pharmacies 231 (283 Total) Other Facilities 239 (848 Total) Kaiser Permanente Washington Medical Centers 261 (25 Total) Index 262 Contact Information back cover kp.org/wa | 1-888-901-4636 | All plans offered and underwritten by Kaiser Foundation Health Plan of Washington i Personal Physicians ADOLESCENT MEDICINE Skagit Regional Health - Arlington Family Bellingham Bay Family Medicine - cont. Medicine 722 N State St 7530 204th St NE (360) 752-2865 Olympia (360) 435-8810 Bowling, Sara Ashley, MD Chaffee, Charles T, MD Fox, Laura Vh, DO Kaiser Permanente Olympia Medical Center Evans, Sarah M, ARNP Hopper, James G, MD 700 Lilly Rd NE Lucianna, Mark A, MD O'Keefe, Karen Davis, MD (360) 923-7000 Schimke, Melana K, MD Skagit Regional Health - Arlington Pediatrics Van Hofwegen, Lisa Marie, MD 875 Wesley St Ste 130 Bellingham Family and Women's Health (360) 435-6525 1116 Key St Ste 106 Kraft, Kelli Malia, ARNP (360) 756-9793 Wood, Franklin Hoover, MD Whitehorse Family Medicine Kopanos, Taynin Kay, ARNP Sprague, Bonnie L, ARNP 875 Wesley St Ste 250 Spokane (360) 435-2233 Bellingham Family Medicine Fletcher, James Rodgers, MD MultiCare Rockwood Main 12 Bellwether Way Ste 230 Janeway, David W, MD (360) 738-7988 400 E 5th Ave Myren, Karen Sue, MD Nuetzmann, John S, DO (509) 838-2531 Carey, Alexandra S, MD Bellevue Fairhaven Family & Sports Medicine -

2015 SSSA Program

Latinos and the Change of a Nation: Implications for the Social Sciences 95th Annual Meeting of the Southwestern Social Science Association April 8 – 11, 2015 Grand Hyatt, Denver Denver, Colorado 1 SSSA Events Time Location Wednesday April 8 Registration & Exhibits 2:00 - 5:00 p.m. Imperial Ballroom SSSA Executive Committee 3:00 - 5:00 p.m. Mount Harvard Nominations Committee Meeting 1 4:00 – 5:30 pm Mount Yale Thursday April 9 Registration & Exhibits 8:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m. Imperial Ballroom Nominations Committee 8:30 - 9:45 a.m. Mount Harvard Membership Committee 8:30 - 9:45 a.m. Mount Yale Budget and Financial Policies Committee 8:30 - 9:45 a.m. Mount Oxford Resolutions Committee 10:00 - 11:15 a.m. Mount Harvard Editorial Policies Committee 10:00 - 11:15 a.m. Mount Oxford Site Policy Committee 10:00 - 11:15 a.m. Mount Yale SSSA Council 1:00 - 3:45 p.m. Mount Oxford SSSA Presidential Address 4:00 - 5:15 p.m. Mount Sopris B SSSA Presidential Reception 5:30 - 7:30 p.m. Mount Evans Friday April 10 Registration & Exhibits 8:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m. Imperial Ballroom SSSA Student Social & Welcome Continental 7:15 – 8:45 a.m. Grand Ballroom Breakfast (FOR REGISTERED STUDENTS ONLY, No Guests or Faculty/Professional Members) SSSA General Business Meeting 1:00 - 2:15 p.m. Grand Ballroom Saturday April 11 Registration 8:00 – 11:00 am Imperial Ballroom 2016 Program Committee 7:15 - 8:30 a.m. Pike’s Peak Getting to Know SSSA 8:30 – 9:15 a.m. -

Colorado Fourteeners Checklist

Colorado Fourteeners Checklist Rank Mountain Peak Mountain Range Elevation Date Climbed 1 Mount Elbert Sawatch Range 14,440 ft 2 Mount Massive Sawatch Range 14,428 ft 3 Mount Harvard Sawatch Range 14,421 ft 4 Blanca Peak Sangre de Cristo Range 14,351 ft 5 La Plata Peak Sawatch Range 14,343 ft 6 Uncompahgre Peak San Juan Mountains 14,321 ft 7 Crestone Peak Sangre de Cristo Range 14,300 ft 8 Mount Lincoln Mosquito Range 14,293 ft 9 Castle Peak Elk Mountains 14,279 ft 10 Grays Peak Front Range 14,278 ft 11 Mount Antero Sawatch Range 14,276 ft 12 Torreys Peak Front Range 14,275 ft 13 Quandary Peak Mosquito Range 14,271 ft 14 Mount Evans Front Range 14,271 ft 15 Longs Peak Front Range 14,259 ft 16 Mount Wilson San Miguel Mountains 14,252 ft 17 Mount Shavano Sawatch Range 14,231 ft 18 Mount Princeton Sawatch Range 14,204 ft 19 Mount Belford Sawatch Range 14,203 ft 20 Crestone Needle Sangre de Cristo Range 14,203 ft 21 Mount Yale Sawatch Range 14,200 ft 22 Mount Bross Mosquito Range 14,178 ft 23 Kit Carson Mountain Sangre de Cristo Range 14,171 ft 24 Maroon Peak Elk Mountains 14,163 ft 25 Tabeguache Peak Sawatch Range 14,162 ft 26 Mount Oxford Collegiate Peaks 14,160 ft 27 Mount Sneffels Sneffels Range 14,158 ft 28 Mount Democrat Mosquito Range 14,155 ft 29 Capitol Peak Elk Mountains 14,137 ft 30 Pikes Peak Front Range 14,115 ft 31 Snowmass Mountain Elk Mountains 14,099 ft 32 Windom Peak Needle Mountains 14,093 ft 33 Mount Eolus San Juan Mountains 14,090 ft 34 Challenger Point Sangre de Cristo Range 14,087 ft 35 Mount Columbia Sawatch Range -

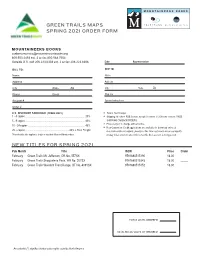

New Titles for Spring 2021 Green Trails Maps Spring

GREEN TRAILS MAPS SPRING 2021 ORDER FORM recreation • lifestyle • conservation MOUNTAINEERS BOOKS [email protected] 800.553.4453 ext. 2 or fax 800.568.7604 Outside U.S. call 206.223.6303 ext. 2 or fax 206.223.6306 Date: Representative: BILL TO: SHIP TO: Name Name Address Address City State Zip City State Zip Phone Email Ship Via Account # Special Instructions Order # U.S. DISCOUNT SCHEDULE (TRADE ONLY) ■ Terms: Net 30 days. 1 - 4 copies ........................................................................................ 20% ■ Shipping: All others FOB Seattle, except for orders of 25 books or more. FREE 5 - 9 copies ........................................................................................ 40% SHIPPING ON BACKORDERS. ■ Prices subject to change without notice. 10 - 24 copies .................................................................................... 45% ■ New Customers: Credit applications are available for download online at 25 + copies ................................................................45% + Free Freight mountaineersbooks.org/mtn_newstore.cfm. New customers are encouraged to This schedule also applies to single or assorted titles and library orders. prepay initial orders to speed delivery while their account is being set up. NEW TITLES FOR SPRING 2021 Pub Month Title ISBN Price Order February Green Trails Mt. Jefferson, OR No. 557SX 9781680515190 18.00 _____ February Green Trails Snoqualmie Pass, WA No. 207SX 9781680515343 18.00 _____ February Green Trails Wasatch Front Range, UT No. 4091SX 9781680515152 18.00 _____ TOTAL UNITS ORDERED TOTAL RETAIL VALUE OF ORDERED An asterisk (*) signifies limited sales rights outside North America. QTY. CODE TITLE PRICE CASE QTY. CODE TITLE PRICE CASE WASHINGTON ____ 9781680513448 Alpine Lakes East Stuart Range, WA No. 208SX $18.00 ____ 9781680514537 Old Scab Mountain, WA No. 272 $8.00 ____ ____ 9781680513455 Alpine Lakes West Stevens Pass, WA No. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae KIRSTEN (KRIS) CHRISTENSEN 1420 Kingsbury Ct, Golden, CO 80401 | 303-929-6901 | [email protected] EDUCATION University of Colorado Denver 2012 Masters of Urban Planning (MURP) Focus: Urban History, Urban Studies University of Colorado Denver 1998 Masters of Social Science (MSS) Focus: Urban and Regional History, Historic Preservation (Graduate Project, Colorado’s Most Endangered Places – establishment of program) University of Colorado Denver 1996 Bachelors of Science, Music Management (BS) Studio Production, Artist Management TEACHING EXPERIENCE Lecturer Fall 2010-Present University of Colorado Denver, College of Liberal Arts and Sciences Department of Geography and Environmental Sciences Courses: Introduction to Urban Studies, Rural Studies, Human Geography Geography of Colorado, World Regional Geography, Populations and Environment Developed course lecture materials, syllabus, exams, instructor of record Liaison – CU Succeed, Department of Geography and Environmental Sciences Feb 2012 - Present Graduate Part-time Instructor Spring 2010 University of Colorado Boulder College of Architecture and Planning Course: Introduction to Historic Preservation Developed course, syllabus, lecture materials, exams, instructor of record Teaching Assistant Fall 2008 – Fall 2009 University of Colorado Boulder College of Architecture and Planning Courses: History of Architecture I and II Graded exams and papers, advised students Graduate Part-time Instructor Fall 2004 - Fall 2006 University of Colorado Boulder College -

Copyrighted Material

20_574310 bindex.qxd 1/28/05 12:00 AM Page 460 Index Arapahoe Basin, 68, 292 Auto racing A AA (American Automo- Arapaho National Forest, Colorado Springs, 175 bile Association), 54 286 Denver, 122 Accommodations, 27, 38–40 Arapaho National Fort Morgan, 237 best, 9–10 Recreation Area, 286 Pueblo, 437 Active sports and recre- Arapaho-Roosevelt National Avery House, 217 ational activities, 60–71 Forest and Pawnee Adams State College–Luther Grasslands, 220, 221, 224 E. Bean Museum, 429 Arcade Amusements, Inc., B aby Doe Tabor Museum, Adventure Golf, 111 172 318 Aerial sports (glider flying Argo Gold Mine, Mill, and Bachelor Historic Tour, 432 and soaring). See also Museum, 138 Bachelor-Syracuse Mine Ballooning A. R. Mitchell Memorial Tour, 403 Boulder, 205 Museum of Western Art, Backcountry ski tours, Colorado Springs, 173 443 Vail, 307 Durango, 374 Art Castings of Colorado, Backcountry yurt system, Airfares, 26–27, 32–33, 53 230 State Forest State Park, Air Force Academy Falcons, Art Center of Estes Park, 222–223 175 246 Backpacking. See Hiking Airlines, 31, 36, 52–53 Art on the Corner, 346 and backpacking Airport security, 32 Aspen, 321–334 Balcony House, 389 Alamosa, 3, 426–430 accommodations, Ballooning, 62, 117–118, Alamosa–Monte Vista 329–333 173, 204 National Wildlife museums, art centers, and Banana Fun Park, 346 Refuges, 430 historic sites, 327–329 Bandimere Speedway, 122 Alpine Slide music festivals, 328 Barr Lake, 66 Durango Mountain Resort, nightlife, 334 Barr Lake State Park, 374 restaurants, 333–334 118, 121 Winter Park, 286 -

COLORADO CONTINENTAL DIVIDE TRAIL COALITION VISIT COLORADO! Day & Overnight Hikes on the Continental Divide Trail

CONTINENTAL DIVIDE NATIONAL SCENIC TRAIL DAY & OVERNIGHT HIKES: COLORADO CONTINENTAL DIVIDE TRAIL COALITION VISIT COLORADO! Day & Overnight Hikes on the Continental Divide Trail THE CENTENNIAL STATE The Colorado Rockies are the quintessential CDT experience! The CDT traverses 800 miles of these majestic and challenging peaks dotted with abandoned homesteads and ghost towns, and crosses the ancestral lands of the Ute, Eastern Shoshone, and Cheyenne peoples. The CDT winds through some of Colorado’s most incredible landscapes: the spectacular alpine tundra of the South San Juan, Weminuche, and La Garita Wildernesses where the CDT remains at or above 11,000 feet for nearly 70 miles; remnants of the late 1800’s ghost town of Hancock that served the Alpine Tunnel; the awe-inspiring Collegiate Peaks near Leadville, the highest incorporated city in America; geologic oddities like The Window, Knife Edge, and Devil’s Thumb; the towering 14,270 foot Grays Peak – the highest point on the CDT; Rocky Mountain National Park with its rugged snow-capped skyline; the remote Never Summer Wilderness; and the broad valleys and numerous glacial lakes and cirques of the Mount Zirkel Wilderness. You might also encounter moose, mountain goats, bighorn sheep, marmots, and pika on the CDT in Colorado. In this guide, you’ll find Colorado’s best day and overnight hikes on the CDT, organized south to north. ELEVATION: The average elevation of the CDT in Colorado is 10,978 ft, and all of the hikes listed in this guide begin at elevations above 8,000 ft. Remember to bring plenty of water, sun protection, and extra food, and know that a hike at elevation will likely be more challenging than the same distance hike at sea level. -

2011, Winter – Bikepacking the CT

News from the Colorado Trail Foundation WINTER 2011 Bikepacking (and Hike-A-Biking) the Colorado Trail By Judd Rohwer (Rohwer, of Sandia Park, New Mexico, is a member of that’s NUTS. Back of the Pack Racing, a team of riders that describes But then the wheels started turning. And I’m not itself as “a fundamental movement that supports the talking about the 29 inchers on my Black Sheep single- theory of ‘me against mainstream.’ Our team attempts speed. I started thinking about the adventure, the to do everything the ‘right way,’ but not your way. We glory ... and the risks. I started thinking about the are a group of engineers, pilots, dreamers and UFO mental preparation, the physical training, the gear ... chasers. One thing is certain. If the race is long enough, and the danger. we will catch you – maybe.” What follows is his The challenge of The Colorado Trail seemed so description of his bikepacking adventures last summer massive compared to the usual 24-hour mountain on The Colorado Trail.) bike races that we train and live for at Back of the Pack Racing. But I wanted to face the challenge head on, so I made a commitment to myself and started planning for a 2011 attempt at the CTR. Then reality hit: the reality of a 500-mile self- supported race hit me straight in the face. Racing myself to the edge of exhaustion and beyond didn’t sound like much fun. So, I quickly convinced myself that the best way to experience the CT was to approach the adventure as a self-supported tour, not a race. -

Mt. Baker Ski Area

Winter Activity Guide Mount Baker Ranger District North Cascades National Park Contacts Get ready for winter adventure! Head east along the Mt. Baker Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest State Road Conditions: /Mt. Baker Ranger District Washington State Dept. of Transportation Highway to access National Forest 810 State Route 20 Dial 511 from within Washington State lands and the popular Mt. Baker Ski Sedro-Woolley, WA 98284 www.wsdot.wa.gov Area. Travel the picturesque North (360) 856-5700 ext. 515 Glacier Public Service Center Washington State Winter Recreation and Cascades Highway along the Skagit 10091 Mt. Baker Highway State Sno-Park Information: Wild & Scenic River System into the Glacier, WA 98244 www.parks.wa.gov/winter heart of the North Cascades. (360) 599-2714 http://www.fs.usda.gov/mbs Mt. Baker Ski Area Take some time for winter discovery but North Cascades National Park Service Ski Area Snow Report: be aware that terrain may be challenging Complex (360) 671-0211 to navigate at times. Mountain weather (360) 854-7200 www.mtbaker.us conditions can change dramatically and www.nps.gov/noca with little warning. Be prepared and check Cross-country ski & snowshoe trails along the Mt. Baker Highway: forecasts before heading out. National Weather Service www.weather.gov www.nooksacknordicskiclub.org Northwest Weather & Avalanche For eagle watching information visit: Travel Tips Center: Skagit River Bald Eagle Interpretive Center Mountain Weather Conditions www.skagiteagle.org • Prepare your vehicle for winter travel. www.nwac.us • Always carry tire chains and a shovel - practice putting tire chains on before you head out. -

Code of Colorado Regulations 1 J

DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Colorado Parks and Wildlife CHAPTER P-7 - PASSES, PERMITS AND REGISTRATIONS 2 CCR 405-7 [Editor’s Notes follow the text of the rules at the end of this CCR Document.] _________________________________________________________________________ ARTICLE I - GENERAL PROVISIONS AND FEES RELATING TO PASSES, PERMITS AND REGISTRATIONS VEHICLE PASSES #700 - VEHICLE PASS 1. Except as otherwise provided in these regulations or by Colorado Revised Statutes, no motor vehicle shall be brought onto any Parks and Outdoor Recreation lands unless a valid pass issued by the Division is properly attached. Passes that are designed to be affixed to the windshield shall be attached to the extreme lower right-hand corner of the vehicle’s windshield in a position so that the pass may be observed and identified. For an annual vehicle pass, including an aspen leaf annual pass to be properly attached to a windshield it must be permanently affixed. Any vehicle without a windshield shall be treated as a special case, but evidence of a pass shall be required. Other types of passes, such as hang tag passes, shall be continuously displayed in the motor vehicle in the manner described on the pass while the motor vehicle is operated or parked on Division properties. 2. No vehicle pass shall be required for: a. Any snowmobile as defined in section 33-14-101, C.R.S.; b. Any off-highway vehicle as defined in section 33-14.5-101(3), C.R.S.; c. Any government-owned vehicle, emergency vehicle, or law enforcement vehicle on official business; d. Any commercial delivery vehicle delivering goods to the park or a park concessionaire when the goods are directly related to the operation of the park or concession; e. -

Profiles of Colorado Roadless Areas

PROFILES OF COLORADO ROADLESS AREAS Prepared by the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region July 23, 2008 INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK 2 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS ARAPAHO-ROOSEVELT NATIONAL FOREST ......................................................................................................10 Bard Creek (23,000 acres) .......................................................................................................................................10 Byers Peak (10,200 acres)........................................................................................................................................12 Cache la Poudre Adjacent Area (3,200 acres)..........................................................................................................13 Cherokee Park (7,600 acres) ....................................................................................................................................14 Comanche Peak Adjacent Areas A - H (45,200 acres).............................................................................................15 Copper Mountain (13,500 acres) .............................................................................................................................19 Crosier Mountain (7,200 acres) ...............................................................................................................................20 Gold Run (6,600 acres) ............................................................................................................................................21