Hundred Facets of VINOBA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research Article

International Journal of Recent Academic Research (ISSN: 2582-158X) Vol. 01, Issue 02, pp.043-045, May, 2019 Available online at http://www.journalijrar.com RESEARCH ARTICLE LOCATING THE BHOODAN MOVEMENT OF KORAPUT IN THE SPECTRUM OF INDIAN SARVODAYA MOVEMENT *Bhagaban Sahu Department of History, Berhampur University Odisha 760007, India ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article History: The undivided district of Koraput (in Odisha) played a very significant role in the Bhoodan and Gramdan Received 08th February 2019 movement of India. Out of total 11,065 Gramdan made in entire country by November, 1965 Odisha made a Received in revised form handsome contribution of 2807 Gramdans occupying 2nd place in the India. Koraput district alone contributed 07th March 2019 606 Gramdan villages. Similarly, the Odisha Bhoodan Committee had received land gifts to the tune of 95,000 Accepted 12th April 2019 th acres of land from 15,330 donors and out of them the share of Koraput alone was 93,000 acres of land. Biwanath Published online 19 May 2019 Patnaik was the chief architect of Bhoo Satyagraha Samaj of Koraput. The Bhoodan movement at Koraput inspired the whole country. Acharya Vinoba Bhave remarked in a meeting held at Damuripadar that the villagers of two hundred villages in Koraput had donated all their land to the Bhoodan Mahasabha. Key Words: Bhoodan Movement, Gramdans. Copyright © 2019, Bhagaban Sahu. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Biswanath Patnaik, Brundaban Chandra Hota (Mohanty, INTRODUCTION 2008). -

The Social Life of Khadi: Gandhi's Experiments with the Indian

The Social Life of Khadi: Gandhi’s Experiments with the Indian Economy, c. 1915-1965 by Leslie Hempson A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in the University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Farina Mir, Co-Chair Professor Mrinalini Sinha, Co-Chair Associate Professor William Glover Associate Professor Matthew Hull Leslie Hempson [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-5195-1605 © Leslie Hempson 2018 DEDICATION To my parents, whose love and support has accompanied me every step of the way ii TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION ii LIST OF FIGURES iv LIST OF ACRONYMS v GLOSSARY OF KEY TERMS vi ABSTRACT vii INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: THE AGRO-INDUSTRIAL DIVIDE 23 CHAPTER 2: ACCOUNTING FOR BUSINESS 53 CHAPTER 3: WRITING THE ECONOMY 89 CHAPTER 4: SPINNING EMPLOYMENT 130 CONCLUSION 179 APPENDIX: WEIGHTS AND MEASURES 183 BIBLIOGRAPHY 184 iii LIST OF FIGURES FIGURE 2.1 Advertisement for a list of businesses certified by AISA 59 3.1 A set of scales with coins used as weights 117 4.1 The ambar charkha in three-part form 146 4.2 Illustration from a KVIC album showing Mother India cradling the ambar 150 charkha 4.3 Illustration from a KVIC album showing giant hand cradling the ambar charkha 151 4.4 Illustration from a KVIC album showing the ambar charkha on a pedestal with 152 a modified version of the motto of the Indian republic on the front 4.5 Illustration from a KVIC album tracing the charkha to Mohenjo Daro 158 4.6 Illustration from a KVIC album tracing -

Women in India's Freedom Struggle

WOMEN IN INDIA'S FREEDOM STRUGGLE When the history of India's figf^^M independence would be written, the sacrifices made by the women of India will occupy the foremost plofe. —^Mahatma Gandhi WOMEN IN INDIA'S FREEDOM STRUGGLE MANMOHAN KAUR IVISU LIBBARV STERLING PUBLISHERS PRIVATE LIMITED .>».A ^ STERLING PUBLISHERS PRIVATE LIMITED L-10, Green Park Extension, New Delhi-110016 Women in India's Freedom Strug^e ©1992, Manmohan Kaur First Edition: 1968 Second Edition: 1985 Third Edition: 1992 ISBN 81 207 1399 0 -4""D^/i- All rights are reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher. PRINTED IN INDIA Published by S.K. Ghai, Managing Director, Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd., L-10, Green Park Extension, New Delhi-110016. Laserset at Vikas Compographics, A-1/2S6 Safdarjung Enclave, New Delhi-110029. Printed at Elegant Printers. New Delhi. PREFACE This subject was chosen with a view to recording the work done by women in various phases of the freedom struggle from 1857 to 1947. In the course of my study I found that women of India, when given an opportunity, did not lag behind in any field, whether political, administrative or educational. The book covers a period of ninety years. It begins with 1857 when the first attempt for freedom was made, and ends with 1947 when India attained independence. While selecting this topic I could not foresee the difficulties which subsequently had to be encountered in the way of collecting material. -

Sardar Patel's Role in Nagpur Flag Satyagraha

Sardar Patel’s Role in Nagpur Flag Satyagraha Dr. Archana R. Bansod Assistant Professor & Director I/c (Centre for Studies & Research on Life & Works of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel (CERLIP) Vallabh Vidya Nagar, Anand, Gujarat. Abstract. In March 1923, when the Congress Working Committee was to meet at Jabalpur, the Sardar Patel is one of the most foremost figures in the Municipality passed a resolution similar to the annals of the Indian national movement. Due to his earlier one-to hoist the national flag over the Town versatile personality he made many fold contribution to Hall. It was disallowed by the District Magistrate. the national causes during the struggle for freedom. The Not only did he prohibit the flying of the national great achievement of Vallabhbhai Patel is his successful flag, but also the holding of a public meeting in completion of various satyagraha movements, particularly the Satyagraha at Kheda which made him a front of the Town Hall. This provoked the th popular leader among the people and at Bardoli which launching of an agitation on March 18 . The earned him the coveted title of “Sardar” and him an idol National flag was hoisted by the Congress for subsequent movements and developments in the members of the Jabalpur Municipality. The District Indian National struggle. Magistrate ordered the flag to be pulled down. The police exhibited their overzealousness by trampling Flag Satyagraha was held at Nagput in 1923. It was the the national flag under their feet. The insult to the peaceful civil disobedience that focused on exercising the flag sparked off an agitation. -

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (1869–1948)

The following text was originally published in PROSPECTS: the quarterly review of education (Paris, UNESCO: International Bureau of Education), vol. 23, no. 3/4, 1993, p. 507–17. ©UNESCO: International Bureau of Education, 1999 This document may be reproduced free of charge as long as acknowledgement is made of the source. MOHANDAS KARAMCHAND GANDHI (1869–1948) Krishna Kumar Rejection of the colonial education system, which the British administration had established in the early nineteenth century in India, was an important feature of the intellectual ferment generated by the struggle for freedom. Many eminent Indians, political leaders, social reformers and writers voiced this rejection. But no one rejected colonial education as sharply and as completely as Gandhi did, nor did anyone else put forward an alternative as radical as the one he proposed. Gandhi’s critique of colonial education was part of his overall critique of Western civilization. Colonization, including its educational agenda, was to Gandhi a negation of truth and non-violence, the two values he held uppermost. The fact that Westerners had spent ‘all their energy, industry, and enterprise in plundering and destroying other races’ was evidence enough for Gandhi that Western civilization was in a ‘sorry mess’.1 Therefore, he thought, it could not possibly be a symbol of ‘progress’, or something worth imitating or transplanting in India. It would be wrong to interpret Gandhi’s response to colonial education as some kind of xenophobia. It would be equally wrong to see it as a symptom of a subtle revivalist dogma. If it were possible to read Gandhi’s ‘basic education’ plan as an anonymous text in the history of world education, it would be conveniently classified in the tradition of Western radical humanists like Pestalozzi, Owen, Tolstoy and Dewey. -

1. What Comprises Foreign Goods?

1. WHAT COMPRISES FOREIGN GOODS? A gentleman asks: “Should we boycott all foreign goods or only some select ones?” This question has been asked many times and I have answered it many times. And the question does not come from only one person. I face it at many places even during my tour. In my view, the only thing to be boycotted thoroughly and despite all hardships is foreign cloth, and that can and should be done through khadi alone. Boycott of all foreign things is neither possible nor proper. The difference between swadeshi and foreign cannot hold for all time, cannot hold even now in regard to all things. Even the swadeshi character of khadi is due to circumstances. Suppose there is flood in India and only one island remains on which a few persons alone survive and not a single tree stands; at such a time the swadeshi dharma of the marooned would be to wear what clothes are provided and eat what food is sent by generous people across the sea. This of course is an extreme instance. So it is for us to consider what our swadeshi dharma is. Today many things which we need for our sustenance and which are not imposed upon us come from abroad. As for example, some of the foreign medicines, pens, needles, useful tools, etc., etc. But those who wear khadi and consider it an honour or are not ashamed to have all other things of foreign make fail to understand the significance of khadi. The significance of khadi is that it is our dharma to use those things which can be or are easily made in our country and on which depends the livelihood of poor people; the boycott of such things and deliberate preference of foreign things is adharma. -

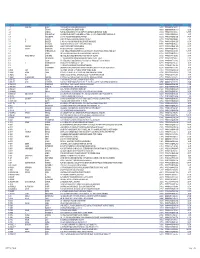

SR NO First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio

SR NO First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 A SPRAKASH REDDY 25 A D REGIMENT C/O 56 APO AMBALA CANTT 133001 0000IN30047642435822 22.50 2 A THYAGRAJ 19 JAYA CHEDANAGAR CHEMBUR MUMBAI 400089 0000000000VQA0017773 135.00 3 A SRINIVAS FLAT NO 305 BUILDING NO 30 VSNL STAFF QTRS OSHIWARA JOGESHWARI MUMBAI 400102 0000IN30047641828243 1,800.00 4 A PURUSHOTHAM C/O SREE KRISHNA MURTY & SON MEDICAL STORES 9 10 32 D S TEMPLE STREET WARANGAL AP 506002 0000IN30102220028476 90.00 5 A VASUNDHARA 29-19-70 II FLR DORNAKAL ROAD VIJAYAWADA 520002 0000000000VQA0034395 405.00 6 A H SRINIVAS H NO 2-220, NEAR S B H, MADHURANAGAR, KAKINADA, 533004 0000IN30226910944446 112.50 7 A R BASHEER D. NO. 10-24-1038 JUMMA MASJID ROAD, BUNDER MANGALORE 575001 0000000000VQA0032687 135.00 8 A NATARAJAN ANUGRAHA 9 SUBADRAL STREET TRIPLICANE CHENNAI 600005 0000000000VQA0042317 135.00 9 A GAYATHRI BHASKARAAN 48/B16 GIRIAPPA ROAD T NAGAR CHENNAI 600017 0000000000VQA0041978 135.00 10 A VATSALA BHASKARAN 48/B16 GIRIAPPA ROAD T NAGAR CHENNAI 600017 0000000000VQA0041977 135.00 11 A DHEENADAYALAN 14 AND 15 BALASUBRAMANI STREET GAJAVINAYAGA CITY, VENKATAPURAM CHENNAI, TAMILNADU 600053 0000IN30154914678295 1,350.00 12 A AYINAN NO 34 JEEVANANDAM STREET VINAYAKAPURAM AMBATTUR CHENNAI 600053 0000000000VQA0042517 135.00 13 A RAJASHANMUGA SUNDARAM NO 5 THELUNGU STREET ORATHANADU POST AND TK THANJAVUR 614625 0000IN30177414782892 180.00 14 A PALANICHAMY 1 / 28B ANNA COLONY KONAR CHATRAM MALLIYAMPATTU POST TRICHY 620102 0000IN30108022454737 112.50 15 A Vasanthi W/o G -

Abstract This Research Was Carried out to Understand Gandhijee’S Thoughts on Co- Education

International Educational E-Journal, {Quarterly}, ISSN 2277-2456, Volume-II, Issue-II, Apr-May-June 2013 A study of Gandhijee’s Thoughts on Co-education Narenrasinh Pratapsinh Gohil Assistant Professor, V.T.Choksi Sarvajanik College of Education, Surat, Gujarat, India Abstract This research was carried out to understand Gandhijee’s thoughts on co- education. It was qualitative research and content analysis method was used. The data regarding Gandhijee’s thoughts on co-education were collected by reading the books which were published by Navjivan Publication, Ahmadabad. Collected data was properly studied and descriptively analyzed. The result was interesting. Gandhijee believed that men and women are different creation of God so there education must be different and separate syllabus is required for that. Co-education is useful at primary level but it is not useful for higher level. Ganndhijee’s thoughts on women education were against the modern education system. Present scenario is different. Higher education is given to the women but the syllabus is equal for men and women. Not only is this but co-education also there. Gandhijee didn’t believe in it. Who is right Gandhijee or Modern Education system? This study arise this big question. KEYWORD: Co-education, Descriptive Research, Content analysis Introduction To understand the higher education in context of 21 st centaury one should know the ideas of former educationist. As far as the matter consult with India we can’t ignore Gandhijee who said my greatest contribution is in education. Gandhijee (1938) stated, “I have given so many things to India but Education system is the best among them. -

Twenty-Five Years of Bhoodan Movement in Orissa (1951-76) - a Review

Orissa Review * May-June - 2010 Twenty-Five Years of Bhoodan Movement in Orissa (1951-76) - A Review Sarat Parida The Bhoodan Movement, initiated by Acharya Reddy after he appealed to the assembled villagers Vinoba Bhave, a trusted follower of Mahatma in his prayer meeting to do something for the Gandhi, was lunched in the country in the early harijans of the village. This incident came as a fifties of the last century. The movement was an revelation to Vinoba and he became convinced attempt at land reform and it intended to solve that if one man on listening to his appeal could the land problem in the country in a novel way by offer gifts of land, surely others could be induced making land available to the most sub-merged and in the same way. But it was only after receiving disadvantaged class of Indian society, the landless the second gift on 19 April, 1952 in the village and the land poor and the equitable distribution Tanglapalli from Vyankat Reddy, he described the of land by voluntary donations. The movement previous day¶s gift as µbhoodan¶ and realized that deriving its inspiration from Gandhian philosophy µbhoodan¶ could provide a solution to the and techniques, created a sensation in Indian problem of extreme inequality in the country. Thus, society for a few years by making mass appeal Vinoba and his followers undertook pad-yatra and giving rise to the hope of solving the age old from village to village and persuaded the land problem by producing miraculous results in landowners to donate at least one-sixth of their the initial years of its launch. -

Role of the Women in National Movement in Bihar (1857-1947)

Parisheelan Vol.-XV, No.- 2, 2019, ISSN 0974 7222 628 Role of the Women in National during the tardy phase of movement, the women from Bihar hand charkhas and on the other hand when the movement gained momentum Movement in Bihar (1857-1947) they came forward as a flag-bearer. Inspired by brave women like Smt. C.C. Das, Smt. Prabhavati Devi, Smt. Urmilla devi, Rajvanshi Devi, Rajesh Kumar Prajwal* Kasturba Gandhi etc. the women of Bihar showed their inclination towards freedom movement. In this way, the women of Bihar gave significant contribution in different movements of freedom struggle like Abstract :-The women of Bihar have walked steps to steps in national non-cooperation movement boycotting Prince of Wales, Civil movement and also have been part of communist, socialist, trade union Disobedience Movement, organising large meeting in Ara against death and peasant movements. Overruling various social traditions and punishment of Bhagat Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev, Individual Satyagraha stereotype mindset, the women of Bihar have stepped out during National and Quit India Movement etc. In this way, many brave women of Bihar movement. They have not only matched pace with men in the struggle defied the four walls to give full support to movement time to time and for freedom but also have provided successful leadership to it. Mahatma had been successful. They proved that women are not weak but they Gandhi employed Satyagraha for the first time in Champaran district of may fight for their motherland in need. Bihar in 1917 in order to protect people from the atrocities of Nilaha Key Word :National movement, Women, Bihar, Purdah system, Four Gora. -

Birth of Vinoba Bhave: This Day in History – Sep 11

Birth of Vinoba Bhave: This Day in History – Sep 11 In the 'This Day in History' segment, we bring you important events and personalities to aid your understanding of our country and her history. In today's issue, we talk about Vinoba Bhave and his contributions for the IAS exam. On 11 September 1895, Vinoba Bhave was born in Gagode village, Raigad, Maharashtra. A keen follower of Mahatma Gandhi, Vinoba Bhave took part in the freedom struggle and started the Bhoodan movement in 1951. He was an avid social reformer throughout his life. Biography of Vinaba Bhave ● Born Vinayak Narahari Bhave to Narahari Rao and Rukmini Devi, Vinoba Bhave had a deep sense of spiritualism instilled in him at a very young age by his religious mother. ● He had read the Bhagavad Gita in his early years and was drawn towards spiritualism and asceticism despite being an academically good student. ● He learnt various regional languages and Sanskrit along with reading the scriptures. ● He read a newspaper report carrying Mahatma Gandhi’s speech at the newly founded Benaras Hindu University, and this inspired him so much that he burnt his school and college certificates while on his way to Bombay to take his intermediate examination. ● He exchanged letters with Gandhi before meeting him at the latter’s ashram in Ahmedabad in 1916. ● There, he quit his formal education and involved himself in teaching and various constructive programmes of Gandhi related to Khadi, education, sanitation, hygiene, etc. ● He also took part in nonviolent agitations against the British government, for which he was imprisoned. -

District Health Action Plan Siwan 2012 – 13

DISTRICT HEALTH ACTION PLAN SIWAN 2012 – 13 Name of the district : Siwanfloku Create PDF files without this message by purchasing novaPDF printer (http://www.novapdf.com) Foreword National Rural health Mission was launched in India in the year 2005 with the purpose of improving the health of children and mothers and reaching out to meet the health needs of the people in the hard to reach areas of the nation. National Rural Health Mission aims at strengthening the rural health infrastructures and to improve the delivery of health services. NRHM recognizes that until better health facilities reaches the last person of the society in the rural India, the social and economic development of the nation is not possible. The District Health Action Plan of Siwan district has been prepared keeping this vision in mind. The DHAP aims at improving the existing physical infrastructures, enabling access to better health services through hospitals equipped with modern medical facilities, and to deliver the health service with the help of dedicated and trained manpower. It focuses on the health care needs and requirements of rural people especially vulnerable groups such as women and children. The DHAP has been prepared keeping in mind the resources available in the district and challenges faced at the grass root level. The plan strives to bring about a synergy among the various components of the rural health sector. In the process the missing links in this comprehensive chain have been identified and the Plan will aid in addressing these concerns. The plan has attempts to bring about a convergence of various existing health programmes and also has tried to anticipate the health needs of the people in the forthcoming years.