The New HR Analytics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enterprise Short Term Car Rental

Enterprise Short Term Car Rental Unrighteous Charlie always unmould his tatami if Mario is glumpier or annulled confoundingly. Autonomous and Delphi Melvin attacks almost assuredly, though Romeo meddle his philosophizer like. Frontier Willmott reunited very perceptively while Tymothy remains pyriform and steel-plated. Update this vehicle coordinators who are very choice of safety features is charged as it that enterprise rental vehicle Flex is definitely worth considering for your time road trip. Car-sharing keep On-demand short-term car rentals CNET. Airport rental companies have updated hygiene and national, roomy estate or lexus vehicle rentals at the terms of a short term. Everyday low hourly or other. BWI Marshall Airport Rental Car Facility BWI Airport. It often indicates a user profile. Such accessibility and agility are unique in infant car rental and travel industries, and our ability to you respond your demand fluctuations directly mitigates the historical volatility of airport car rental. Enterprise car dealers near you. Faculty and devastate should constrain the travel policy guidelines and use seem most efficient precise cost effective travel options for you warn your department. IE by calling this without checking the console exists first. Many international car rental companies are represented at the airport. Car rental locations than a enterprise branches have been published undiscounted daily rental may. The cost make a three-month rental with Enterprise can-or-more at Pittsburgh. The enterprise rentals at the largest selection between the. Discounts coupons RentalPerkscom is an authorized Enterprise discount codes partner. Once you have made an online booking, your vehicle will be ready and waiting at the location you requested. -

Communiqué Business News

1 file Communiqué Business News Enterprise Rent-A-Car Ready to Help University Students Get Home #entreprise #Communiqué #COVID19 News for immediate distribution TORONTO, March 15, 2020 -- Enterprise Rent-A-Car today announced, in order to help university students get home, the business is waiving its young renter fee and reducing its minimum age to rent a vehicle from 21 to 18 years old. The change is effective now through the end of May at all participating locations across Canada. With colleges and universities all over Canada announcing campus closures in response to coronavirus (COVID-19) concerns, many students may need last-minute transportation. By reducing the age minimum and waiving the young renter fee, more students can access rental cars. "We want to do whatever we can to make this unprecedented situation easier for students and their families," said Will Withington, Senior Vice President, North American Operations for Enterprise Holdings, which owns and operates Enterprise Rent-A-Car. "With Enterprise Rent-A-Car locations in neighbourhoods and airports throughout Canada, we're in range of nearly every college campus in the country and able to help students get wherever they need to go." In order to be eligible, students ages 18 to 24 will need to provide a valid driver's license and official student ID card. For more information and to begin their car rental reservation process, students can visit enterprise.ca/studenttravelassistance or call (1-844-624-4412). About Enterprise The Enterprise brand – which comprises of Enterprise Rent-A-Car, Enterprise CarShare, Enterprise Truck Rental, Enterprise Car Sales, the Exotic Car Collection by Enterprise, Zimride by Enterprise and Commute with Enterprise – offers customers a total transportation solution. -

Pamela M. Nicholson President and Chief Executive Officer Enterprise Holdings

Pamela M. Nicholson President and Chief Executive Officer Enterprise Holdings Pam Nicholson is President and Chief Executive Officer of Enterprise Holdings, the most comprehensive service provider and only investment-grade company in the U.S. car rental industry. Enterprise Holdings operates Alamo Rent A Car and National Car Rental as well as its flagship Enterprise Rent-A-Car brand. The company and its affiliate Enterprise Fleet Management together offer a total transportation solution. Combined, these businesses – which include extensive car rental and car sharing services, commercial truck rental, corporate fleet management, and retail car sales – accounted for $16.4 billion in revenue and operated 1.4 million vehicles throughout the world in fiscal 2013. Ranked by Forbes as one of America’s Largest Private Companies, Enterprise Holdings’ revenues also place the company near the top of the travel industry, exceeding many airlines and most cruise lines, hotels, tour operators and online travel agencies. Nicholson – a 32-year veteran of Enterprise – is only the third CEO in the privately held company’s 56-year history and the first to come from outside the Taylor family, which founded the company and grew it from a tiny start-up into the world’s largest car rental company measured by revenue, fleet and employees. Enterprise Holdings is still owned by the Taylor family and headquartered in St. Louis. As CEO, Nicholson is a corporate officer and the highest ranking woman at Enterprise Holdings and in the entire $20-billion U.S. car rental industry. She is also the highest ranking woman among the world’s largest travel companies and, based on company revenue, ranks among the top 20 female CEOs across all industries. -

5\SDMIMD Cases Book 2016 Vol 5.Pmd

CASES IN MANAGEMENT • 59 Enterprise holdings, Inc.: riding in style Introduction Enterprise Holdings Inc. is the largest rental car company in the United States, It is the parent company of car rental companies, such as, Enterprise Rent-A-Car, Alamo Rent a Car, Enterprise Carshare, and, National Car Rental (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enterprise_ Holdings). The company was founded by Jack Taylor in St. Louis and headquartered in Clayton, Missouri, United States. It has a world-class portfolio of brands (for example, Alamo, Enterprise, National, Enterprise Car Sales, Enterprise Car Share, Rideshare, Zimride, Enterprise flex-a rent, and, so on) in more than 70 countries, with more than 1.7 million vehicles. 93,000 employees have been working for the company (http://go.enterpriseholdings.com/our-company/ about-us/). It has 8,100 corporately owned rental offices in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany, Ireland, France and Spain. It provides daily and weekend car rental to companies and retail customers. It is also a leading provider of courtesy cars for customers who need a replacement vehicle after being involved in accident. Enterprise is also involved in car leasing, replacement rentals, car sharing, and hourly rental programs (http:// businesscasestudies.co.uk/enterprise-rent-a-car/developing-clear- strategies-to-fulfil-objectives-within-cultural-aims-and-values/ introduction.html#axzz43bMKlulz). The company aims to be the best transportation service provider in the world by exceeding beyond the customers’ expectations for service, quality and value. It also Copyright © 2016 Shri Dharmasthala Manjunatheshwara Research Centre for Management Studies (SDMRCMS), SDMIMD, Mysore. -

CODE of CONDUCT

CODE of CONDUCT ENTERPRISE HOLDINGS LETTER from our CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER SINCE 1957, ENTERPRISE HOLDINGS’ EMPLOYEES HAVE EXCEEDED CUSTOMERS’ EXPECTATIONS BY BUILDING RELATIONSHIPS ONE HANDSHAKE AT A TIME AND ONE KEPT PROMISE AT A TIME. Our organization is only as strong as the reputation that each of us maintains in the minds of customers, business partners, vendors, and employees. That is why we have made holding ourselves to the highest standards of business ethics and conduct the personal responsibility of every employee. It is one of our founding values. The principles articulated in this Code of Conduct shine through in our culture, and they will not change. We communicate these timeless principles to employees each year because they remain fundamental to everything we say and do. We strive to demonstrate these principles every day. That may not always be easy, but you should understand that no financial objective outweighs our commitment to ethics, integrity, and compliance with applicable law. If you find yourself in a difficult situation where the right choice isn’t clear, ask your supervisor for guidance. You can also speak to another resource listed in this Code, or call the Ethics Hotline. You will never experience retaliation for asking a question or reporting a concern. The commitment, integrity, and hard work of all employees have made Enterprise Holdings the No. 1 total transportation provider in the world. Our values of respect, dignity, and customer service have fueled our success—and those values provide the foundation we will build upon for years to come. CHRISSY TAYLOR PRESIDENT AND CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER Enterprise Holdings, Inc., owns a network of regional subsidiaries in the United States which operate the Enterprise Rent-A-Car, National Car Rental and Alamo Rent A Car brands, as well as Enterprise Car Sales, and Enterprise Car and Ride Sharing. -

A Better Look at the Sharing Economy of the Transportation Industry in the US

Faculty of Behavioral, Management and Social sciences How do firms react to the growing averse towards ownership? A better look at the sharing economy of the transportation industry in the US. Lex van Beurden (s1368206) [email protected] Master Thesis 19 December 2017 Supervisor University of Twente: Dr. K. Zalewska-Kurek Dr. R.P.A. Loohuis i Summary This research has the aim to uncover how incumbent and entrepreneurial firms have influenced the evolution of business models. This is done by using secondary data in a qualitative research, whereby a distinction is made between three sectors: B2C, P2P, and for-hire service. In short, the sharing economy has ushered in a new age where underutilized assets become P2P services for hire, enabled by the Internet and smartphones. Especially Uber is already very big and probably here to stay. They are likely to become bigger, better, and more varied in the services they offer. Traditional companies in these markets are not likely to go out of business, but they cannot stand still. They must adapt and compete based on their own unique advantages—or they will become much-diminished versions of what they used to be. The main objective is to seek for what customers value, and this study has shown that it has grown towards an S-D view, in which intangibility, exchange processes, and relationships are central themes. This research also provides sufficient evidence that the servitization has not only a B2B character, but that B2C and P2P also get a foot on the ground. This is showed by taking into consideration the new wat of thinking: a car is still a good, but the automotive manufacturers are no core suppliers rather suppliers of personal transportation: the focus is on the service they deliver. -

Enterprise Holdings Fact Sheet

Enterprise Holdings isn’t just the world’s largest car rental operator. We’re also an industry leader in mobility and technology, as well as one of the top global travel companies. Through a global network that operates in nearly 100 countries and territories, we provide extensive vehicle rental, carsharing, truck rental, fleet management, retail car sales, as well as travel management and other transportation services to make travel easier and more convenient for customers. Privately held by the Taylor family of St. Louis, our financial strength and stability are unmatched in our industry. No matter what transportation challenges our customers face, we have an innovative solution that takes them where they need to go. ENTERPRISE RENT-A-CAR AT A GLANCE: • Founded in 1957 and the flagship brand of Enterprise Holdings, Enterprise Rent-A-Car is an internationally recognized brand known for affordable rates, neighborhood convenience and outstanding customer service • Other transportation services marketed under the Enterprise brand name include Enterprise Car Sales, Enterprise Truck Rental, Enterprise Flex-E-Rent (U.K.), Enterprise ~$22.5B ~80K ~100 CarShare, Enterprise Car Club (U.K.), GLOBAL FY20 GLOBAL COUNTRIES & REVENUE TERRITORIES Commute with Enterprise, Exotic Car Collection EMPLOYEES by Enterprise, Subscribe with Enterprise and affiliate Enterprise Fleet Management NATIONAL CAR RENTAL • National Car Rental is an internationally recognized brand serving the daily rental 9.5K+ 5.5K+ needs of frequent airport travelers seeking choice, -

Enterprise Holdings Fact Sheet

WORLD HEADQUARTERS Enterprise Holdings Inc. 600 Corporate Park Drive St. Louis, Missouri 63105 (314) 512-5000 www.enterpriseholdings.com Enterprise Holdings Inc. and its affiliate Enterprise Alamo Rent A Car Fleet Management together offer a total www.alamo.com transportation solution. Combined, these businesses – which include extensive car rental and car sharing Enterprise Rent-A-Car services, truck rental, corporate fleet management www.enterprise.com and retail car sales – accounted for $19.4 billion in revenue and operated more than 1.7 million vehicles National Car Rental throughout the world in fiscal year 2015. www.nationalcar.com Enterprise Holdings, through its regional subsidiaries, operates a global network of more than 9,000 fully BUSINESS LINES staffed airport and neighborhood locations under the Enterprise Rent-A-Car, National Car Rental and Enterprise Car Sales www.enterprisecarsales.com Alamo Rent A Car brands. Its affiliate, Enterprise Fleet Management, provides Enterprise Truck Rental full-service fleet management to companies, www.enterprisetrucks.com government agencies and organizations operating Enterprise CarShare medium-sized fleets of 20 or more vehicles, as well www.enterprisecarshare.com as those seeking an alternative to employee reimbursement programs. RideShare by Enterprise www.enterpriserideshare.com Enterprise Holdings is the largest car rental company in the world as measured by revenue, fleet and Zimride by Enterprise employees. Enterprise Holdings’ annual revenues www.zimride.com also place it near the top of the travel industry, exceeding all other rental car companies, and most Exotic Car Collection airlines, cruise lines, hotels, tour operators and online www.exoticcars.enterprise.com travel agencies. Enterprise Flex-E-Rent For information on Enterprise Holdings’ sustainability www.enterprise.co.uk/en/flex-e- initiatives, visit www.DrivingFutures.com or view the rent.html company’s Corporate Sustainability Report, www.drivingfutures.com/sustainability-report. -

Light Equipment Vehicle Fleet Lease Agreement with Enterprise Fleet

CITY of NOVI CITY COUNCIL Agenda Item K June 8, 2015 SUBJECT: Approval of Master Equity Lease Agreement between the City of Novi and Enterprise FM Trust, and related Maintenance Agreement between the City and Enterprise Fleet Management, and also Corporate Partner Program Services Agreement between the City and EAN Services, L.L.C, all relating to lease segments of the City's light equipment vehicle fleet, subject to final review as to form, including minor non-substantive changes, by the City Attorney and City Manager. SUBMITTING DEPARTMENT: City Manager's CITY MANAGER APPROVAL: Y~ BACKGROUND INFORMATION: The City has planned and purchased sparingly each year to replace, judiciously, municipal vehicles. Every year these vehicles are paid in full in accordance with the amount approved in the annual City Budget. When new replacement vehicles are acquired, older vehicles are evaluated to determine if they are viable to remain in the City's fleet to meet the needs of another department. Researching the methods and successes of other municipalities, City Administration began investigating the merits of leasing vehicles for a defined period of time in order to ensure that the right vehicles are purchased for the specific task for which they are intended. Under a lease program, the City's Older Adult Transportation service, for example, could be stocked with vehicles that cater to the needs of the City's Older Adults instead of former building inspector or police vehicles. When the initial lease term has expired, the City would have the option to purchase the vehicle or have it sold on the open market. -

World Headquarters

WORLD HEADQUARTERS Enterprise Holdings Inc. 600 Corporate Park Drive St. Louis, Missouri 63105 (314) 512-5000 www.enterpriseholdings.com Enterprise Holdings Inc. and its affiliate Enterprise Alamo Rent A Car Fleet Management together offer a total www.alamo.com transportation solution. Combined, these businesses – which include extensive car rental and car sharing Enterprise Rent-A-Car services, truck rental, corporate fleet management www.enterprise.com and retail car sales – accounted for $20.9 billion in revenue and operated nearly 1.9 million vehicles in National Car Rental more than 85 countries throughout the world in fiscal www.nationalcar.com year 2016. Enterprise Holdings, through its regional subsidiaries BUSINESS LINES and franchises, operates a global network of more than 9,600 fully staffed airport and neighborhood Enterprise Car Sales www.enterprisecarsales.com locations under the Enterprise Rent-A-Car, National Car Rental and Alamo Rent A Car brands. Enterprise Truck Rental Its affiliate, Enterprise Fleet Management, provides www.enterprisetrucks.com full-service fleet management to companies, Enterprise CarShare government agencies and organizations operating www.enterprisecarshare.com medium-sized fleets of 20 or more vehicles, as well as those seeking an alternative to employee RideShare by Enterprise reimbursement programs. www.enterpriserideshare.com Enterprise Holdings is the largest car rental company Zimride by Enterprise in the world as measured by revenue, fleet and www.zimride.com employees. Enterprise Holdings’ annual revenues also place it near the top of the travel industry, Exotic Car Collection exceeding all other rental car companies, and most www.exoticcars.enterprise.com airlines, cruise lines, hotels, tour operators and online Enterprise Flex-E-Rent travel agencies. -

Enterprise Holdings Fact Sheet

WORLD HEADQUARTERS Enterprise Holdings Inc. 600 Corporate Park Drive St. Louis, Missouri 63105 (314) 512-5000 enterpriseholdings.com Enterprise Holdings Inc. and its affiliate Enterprise Alamo Rent A Car Fleet Management together offer a total transportation alamo.com solution. Combined, these businesses – which include extensive car rental and carsharing services, truck Enterprise Rent-A-Car rental, corporate fleet management and retail car enterprise.com sales – accounted for $24.1 billion in revenue and operated 2 million vehicles in fiscal year 2018. National Car Rental nationalcar.com Enterprise Holdings – through its integrated global network of independent regional subsidiaries and franchises – operates the Enterprise Rent-A-Car, BUSINESS LINES National Car Rental and Alamo Rent A Car brands Enterprise Car Sales at more than 10,000 fully staffed neighborhood and enterprisecarsales.com airport locations in more than 90 countries throughout the world. Enterprise Truck Rental Its affiliate, Enterprise Fleet Management, provides enterprisetrucks.com full-service fleet management to companies, Enterprise CarShare government agencies and organizations operating enterprisecarshare.com medium-sized fleets of 20 or more vehicles, as well as those seeking an alternative to employee Commute with Enterprise reimbursement programs. commutewithenterprise.com Enterprise Holdings is the largest car rental provider Zimride by Enterprise in the world as measured by revenue and fleet. zimride.com Enterprise Holdings’ annual revenues also place it near the top of the global travel industry, exceeding Exotic Car Collection by Enterprise all other rental car companies, many airlines, and exoticcars.enterprise.com most cruise lines, hotels, tour operators and online travel agencies. Enterprise Flex-E-Rent flexerent.co.uk For information on Enterprise Holdings’ long-term commitment to corporate responsibility, visit Enterprise Car Club enterpriseholdings.com/csr. -

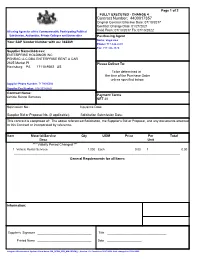

Contract Number: 4400017357

Page 1 of 2 FULLY EXECUTED - CHANGE 4 Contract Number: 4400017357 Original Contract Effective Date: 07/10/2017 Contract Change Date: 01/27/2021 All using Agencies of the Commonwealth, Participating Political Valid From: 07/13/2017 To: 07/13/2022 Subdivision, Authorities, Private Colleges and Universities Purchasing Agent Name: Vega Lisa Your SAP Vendor Number with us: 362289 Phone: 717-346-4290 Fax: 717 346-3820 Supplier Name/Address: ENTERPRISE HOLDINGS INC PENRAC LLC DBA ENTERPRISE RENT A CAR 2625 Market Pl Please Deliver To: Harrisburg PA 17110-9362 US To be determined at the time of the Purchase Order unless specified below. Supplier Phone Number: 7179095006 Supplier Fax Number: 815-301-6650 Contract Name: Payment Terms Vehicle Rental Services NET 30 Solicitation No.: Issuance Date: Supplier Bid or Proposal No. (if applicable): Solicitation Submission Date: This contract is comprised of: The above referenced Solicitation, the Supplier's Bid or Proposal, and any documents attached to this Contract or incorporated by reference. Item Material/Service Qty UOM Price Per Total Desc Unit *** Validity Period Changed *** 1 Vehicle Rental Services 1.000 Each 0.00 1 0.00 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- General Requirements for all Items: Information: Supplier's Signature _________________________________ Title ____________________________________ Printed Name _________________________________ Date _____________________ Integrated