A Critical Analysis of the Representation of Serial Murderers in America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

October 2012 Highlights Documentaries

OCTOBER 2012 HIGHLIGHTS ** Denotes programs with artwork available on Investigation Discovery’s Press Website All Times ET // All airdates are subject to change INVESTIGATION DISCOVERY PRESS CONTACTS: Jordyn Linsk Charlotte Bigford Publicist Publicist 240-662-2421, [email protected] 240-662-3125, [email protected] DOCUMENTARIES ID FILMS: TELLING AMY’S STORY ** TV-PG (V) One-Hour Documentary Premieres Monday, October 8 at 7 PM ET By laying bare one woman's story and the many opportunities to alter its outcome, this October, Investigation Discovery commemorates Domestic Violence Awareness Month in the hope of educating, empowering, and even saving lives. On November 8, 2001, Amy Homan McGee was killed by her abusive husband of four years while her children waited outside in the car. Hosted by actress and advocate Mariska Hargitay, and told by Detective Deirdri Fishel, TELLING AMY’S STORY follows the timeline of the tragic domestic violence homicide that occurred in central Pennsylvania. The victim’s parents and co-workers, law enforcement officers, and court personnel share their perspectives on what happened to Amy in the weeks, months, and years leading up to her death. ID FILMS: WERNER HERZOG'S INTO THE ABYSS: A TALE OF LIFE, A TALE OF DEATH ** TV-14 Feature-Length Documentary Makes Its World TV Premiere on Tuesday, October 23 at 8 PM ET Werner Herzog’s INTO THE ABYSS debuted in September 2011 to rave reviews and festival buzz from Telluride to Toronto. Exploring the intricate details and emotional aftermath of a triple homicide in Conroe, Texas, Herzog sought to better understand the impact of life in prison and the shattering effects of the death penalty. -

First-Run Smoking Presentations in U.S. Movies 1999-2006

First-Run Smoking Presentations in U.S. Movies 1999-2006 Jonathan R. Polansky Stanton Glantz, PhD CENTER FOR TOBAccO CONTROL RESEARCH AND EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN FRANCISCO SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94143 April 2007 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Smoking among American adults fell by half between 1950 and 2002, yet smoking on U.S. movie screens reached historic heights in 2002, topping levels observed a half century earlier.1 Tobacco’s comeback in movies has serious public health implications, because smoking on screen stimulates adolescents to start smoking,2,3 accounting for an estimated 52% of adolescent smoking initiation. Equally important, researchers have observed a dose-response relationship between teens’ exposure to on-screen smoking and smoking initiation: the greater teens’ exposure to smoking in movies, the more likely they are to start smoking. Conversely, if their exposure to smoking in movies were reduced, proportionately fewer teens would likely start smoking. To track smoking trends at the movies, previous analyses have studied the U.S. motion picture industry’s top-grossing films with the heaviest advertising support, deepest audience penetration, and highest box office earnings.4,5 This report is unique in examining the U.S. movie industry’s total output, and also in identifying smoking movies, tobacco incidents, and tobacco impressions with the companies that produced and/or distributed the films — and with their parent corporations, which claim responsibility for tobacco content choices. Examining Hollywood’s product line-up, before and after the public voted at the box office, sheds light on individual studios’ content decisions and industry-wide production patterns amenable to policy reform. -

Peer Reviewed Commentary Journal Article Citation

2018 - Peer Reviewed Commentary Journal Article Citation: Nathan Scudder, James Robertson, Sally F. Kelty, Simon J. Walsh & Dennis McNevin (2018) Crowdsourced and crowdfunded: the future of forensic DNA?, Australian Journal of Forensic Sciences, DOI: 10.1080/00450618.2018.1486456 Version: This is an Accepted Manuscript of a work that was published by Taylor & Francis in Australian Journal of Forensic Sciences on 5 July 2018 which has been published at https://doi.org/10.1080/00450618.2018.1486456 Changes resulting from the publishing process may not be reflected in this document. Crowdsourced and crowdfunded: The future of forensic DNA? Nathan Scudder a, c James Robertson a Sally F. Kelty b Simon J. Walsh c Dennis McNevin d a National Centre for Forensic Studies, Faculty of Science and Technology, University of Canberra, ACT 2617, Australia b Centre for Applied Psychology, Faculty of Health, University of Canberra, ACT 2617, Australia c Australian Federal Police, GPO Box 401, Canberra ACT 2601, Australia d Centre for Forensic Science, School of Mathematical and Physical Sciences, Faculty of Science, University of Technology Sydney, Broadway, NSW, 2007, Australia Corresponding author: [email protected] Word Count: 2,956 (with references) 1 Crowdsourced and crowdfunded: The future of forensic DNA? Forensic DNA analysis is dependent on comparing the known and the unknown. Expand the number of known profiles, and the likelihood of a successful match increases. Forensic use of DNA is moving towards comparing samples of unknown origin with publicly available genetic data, such as the records held by genetic genealogy providers. Use of forensic genetic genealogy has yielded a number of recent high-profile successes but has raised ethical and privacy concerns. -

Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment

Shirley Papers 48 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title Research Materials Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment Capital Punishment 152 1 Newspaper clippings, 1951-1988 2 Newspaper clippings, 1891-1938 3 Newspaper clippings, 1990-1993 4 Newspaper clippings, 1994 5 Newspaper clippings, 1995 6 Newspaper clippings, 1996 7 Newspaper clippings, 1997 153 1 Newspaper clippings, 1998 2 Newspaper clippings, 1999 3 Newspaper clippings, 2000 4 Newspaper clippings, 2001-2002 Crime Cases Arizona 154 1 Cochise County 2 Coconino County 3 Gila County 4 Graham County 5-7 Maricopa County 8 Mohave County 9 Navajo County 10 Pima County 11 Pinal County 12 Santa Cruz County 13 Yavapai County 14 Yuma County Arkansas 155 1 Arkansas County 2 Ashley County 3 Baxter County 4 Benton County 5 Boone County 6 Calhoun County 7 Carroll County 8 Clark County 9 Clay County 10 Cleveland County 11 Columbia County 12 Conway County 13 Craighead County 14 Crawford County 15 Crittendon County 16 Cross County 17 Dallas County 18 Faulkner County 19 Franklin County Shirley Papers 49 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title 20 Fulton County 21 Garland County 22 Grant County 23 Greene County 24 Hot Springs County 25 Howard County 26 Independence County 27 Izard County 28 Jackson County 29 Jefferson County 30 Johnson County 31 Lafayette County 32 Lincoln County 33 Little River County 34 Logan County 35 Lonoke County 36 Madison County 37 Marion County 156 1 Miller County 2 Mississippi County 3 Monroe County 4 Montgomery County -

They Have Names, Too: a Case Study on the First Five Victims of the Green River Killer: Examining the Construction of Society and Its Creation of Victim Availability

Seattle University ScholarWorks @ SeattleU Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Undergraduate Honors Theses Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies 2020 They Have Names, Too: A Case Study on the First Five Victims of the Green River Killer: Examining the Construction of Society and Its Creation of Victim Availability Natalie V. Castillo Seattle University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.seattleu.edu/wgst-theses Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Castillo, Natalie V., "They Have Names, Too: A Case Study on the First Five Victims of the Green River Killer: Examining the Construction of Society and Its Creation of Victim Availability" (2020). Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Undergraduate Honors Theses. 2. https://scholarworks.seattleu.edu/wgst-theses/2 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at ScholarWorks @ SeattleU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ SeattleU. They Have Names, Too: A Case Study on the First Five Victims of the Green River Killer: Examining the Construction of Society and Its Creation of Victim Availability Natalie V. Castillo Seattle University 13 June 2020 Bachelor of Arts in Criminal Justice with Departmental Honors Bachelor of Arts in Women and Gender Studies with Departmental Honors Castillo: FIRST FIVE VICTIMS OF THE GREEN RIVER KILLER 2 Table of Contents I Acknowledgments -

Teen Stabbing Questions Still Unanswered What Motivated 14-Year-Old Boy to Attack Family?

Save $86.25 with coupons in today’s paper Penn State holds The Kirby at 30 off late Honoring the Center’s charge rich history and its to beat Temple impact on the region SPORTS • 1C SPECIAL SECTION Sunday, September 18, 2016 BREAKING NEWS AT TIMESLEADER.COM '365/=[+<</M /88=C6@+83+sǍL Teen stabbing questions still unanswered What motivated 14-year-old boy to attack family? By Bill O’Boyle Sinoracki in the chest, causing Sinoracki’s wife, Bobbi Jo, 36, ,9,9C6/Ľ>37/=6/+./<L-97 his death. and the couple’s 17-year-old Investigators say Hocken- daughter. KINGSTON TWP. — Specu- berry, 14, of 145 S. Lehigh A preliminary hearing lation has been rampant since St. — located adjacent to the for Hockenberry, originally last Sunday when a 14-year-old Sinoracki home — entered 7 scheduled for Sept. 22, has boy entered his neighbors’ Orchard St. and stabbed three been continued at the request house in the middle of the day members of the Sinoracki fam- of his attorney, Frank Nocito. and stabbed three people, kill- According to the office of ing one. ily. Hockenberry is charged Magisterial District Justice Everyone connected to the James Tupper and Kingston case and the general public with homicide, aggravated assault, simple assault, reck- Township Police Chief Michael have been wondering what Moravec, the hearing will be lessly endangering another Photo courtesy of GoFundMe could have motivated the held at 9:30 a.m. Nov. 7 at person and burglary in connec- In this photo taken from the GoFundMe account page set up for the Sinoracki accused, Zachary Hocken- Tupper’s office, 11 Carverton family, David Sinoracki is shown with his wife, Bobbi Jo, and their three children, berry, to walk into a home on tion with the death of David Megan 17; Madison, 14; and David Jr., 11. -

Spotted.Yankton.Net...Upload & Share Your Photos For

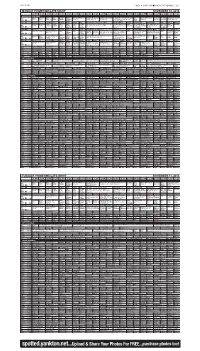

PAGE 10B PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 7, 2014 MONDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT NOVEMBER 10, 2014 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS Arthur Å Arthur Å Wild Wild Martha Nightly PBS NewsHour (N) (In Antiques Roadshow Antiques Roadshow Ice Warriors -- USA Sled Hockey BBC Charlie Rose (N) (In Tavis Smi- The Mind Antiques Roadshow PBS (DVS) (DVS) Kratts Å Kratts Å Speaks Business Stereo) Å “Miami Beach” Å “Madison” Å The U.S. sled hockey team. (In World Stereo) Å ley (N) Å of a Chef “Miami Beach” Å KUSD ^ 8 ^ Report Stereo) Å (DVS) News Å KTIV $ 4 $ Queen Latifah Ellen DeGeneres News 4 News News 4 Ent The Voice The artists perform. (N) Å The Blacklist (N) News 4 Tonight Show Seth Meyers Daly News 4 Extra (N) Hot Bench Hot Bench Judge Judge KDLT NBC KDLT The Big The Voice “The Live Playoffs, Night 1” The art- The Blacklist Red and KDLT The Tonight Show Late Night With Seth Last Call KDLT (Off Air) NBC (N) Å (N) Å Judy (N) Judy (N) News Nightly News Bang ists perform. (N) (In Stereo Live) Å Berlin head to Moscow. News Å Starring Jimmy Fallon Meyers (N) (In Ste- With Car- News Å KDLT % 5 % Å Å (N) Å News (N) (N) Å Theory (N) Å (In Stereo) Å reo) Å son Daly KCAU ) 6 ) Dr. -

October 2011

OctOber 2011 7:00 PM ET/4:00 PM PT 3:15 PM ET/12:15 PM PT 1:00 PM ET/10:00 AM PT 6:00 PM CT/5:00 PM MT 2:15 PM CT/1:15 PM MT 12:00 PM CT/11:00 AM MT The Wild Bunch - In Retro/Na- Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves Spaceballs tional Film Registry 5:45 PM ET/2:45 PM PT 2:45 PM ET/11:45 AM PT SATURDAY, OCTOBER 1 9:30 PM ET/6:30 PM PT 4:45 PM CT/3:45 PM MT 1:45 PM CT/12:45 PM MT 12:00 AM ET/9:00 PM PT 8:30 PM CT/7:30 PM MT Unforgiven - National Film Regis- Gremlins - Spotlight Feature 11:00 PM CT/10:00 PM MT Unforgiven - National Film Regis- try/Spotlight Feature 4:35 PM ET/1:35 PM PT The Country Bears - KIDS try/Spotlight Feature 8:00 PM ET/5:00 PM PT 3:35 PM CT/2:35 PM MT FIRST!/kidScene “Friday Nights” 11:45 PM ET/8:45 PM PT 7:00 PM CT/6:00 PM MT Gremlins 2: The New Batch 1:30 AM ET/10:30 PM PT 10:45 PM CT/9:45 PM MT A Face in the Crowd - In Retro/Na- 6:30 PM ET/3:30 PM PT 12:30 AM CT/11:30 PM MT The Wild Bunch - In Retro/Na- tional Film Registry 5:30 PM CT/4:30 PM MT White Squall tional Film Registry 10:15 PM ET/7:15 PM PT The Lost Boys 3:45 AM ET/12:45 AM PT 9:15 PM CT/8:15 PM MT 8:15 PM ET/5:15 PM PT 2:45 AM CT/1:45 AM MT SUNDAY, OCTOBER 2 Papillon - In Retro 7:15 PM CT/6:15 PM MT Everybody’s All American 2:15 AM ET/11:15 PM PT Beetlejuice 6:00 AM ET/3:00 AM PT 1:15 AM CT/12:15 AM MT MONDAY, OCTOBER 3 10:00 PM ET/7:00 PM PT 5:00 AM CT/4:00 AM MT Unforgiven - National Film Regis- 1:00 AM ET/10:00 PM PT 9:00 PM CT/8:00 PM MT Zula Patrol: Animal Adventures in try/Spotlight Feature 12:00 AM CT/11:00 PM MT Big Fish Space 4:30 AM ET/1:30 AM PT -

Societies for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals

State of New Jersey Commission of Investigation SOCIETIES FOR THE PREVENTION OF CRUELTY TO ANIMALS December 2000 State of New Jersey Commission of Investigation SOCIETIES FOR THE PREVENTION OF CRUELTY TO ANIMALS The Report is available on the Commission’s Web Site at www.state.nj.us/sci TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................ 1 HISTORY OF THE SPCAs ....................................................................................... 3 AUTHORITY OF THE SPCAs IN NEW JERSEY ................................................. 5 Arrest Powers .............................................................................................. 7 Search and Seizure Powers ......................................................................... 8 Power to Carry Weapons ............................................................................ 9 Red Lights and Sirens ................................................................................. 10 A Question of Effectiveness ............................................................................. 13 Recordkeeping ............................................................................................ 15 PROFILE OF THE COUNTY SPCAs ..................................................................... 17 Overview of the County Societies .................................................................... 18 The County Societies ....................................................................................... -

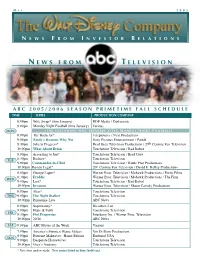

N E W S F R O M T E L E V I S I O N

M A Y 2 0 0 5 N E W S F R O M I N V E S T O R R E L A T I O N S N E W S F R O M T E L E V I S I O N A B C 2 0 0 5 / 2 0 0 6 S E A S O N P R I M E T I M E F A L L S C H E D U L E TIME SERIES PRODUCTION COMPANY 8:00pm Wife Swap* (thru January) RDF Media / Diplomatic 9:00pm Monday Night Football (thru January) Various MON ( T H E F O L L O W I N G W I L L P R E M I E R E A F T E R M O N D A Y N I G H T F O O T B A L L ) 8:00pm The Bachelor* Telepictures / Next Productions 9:00pm Emily’s Reasons Why Not Sony Pictures Entertainment / Pariah 9:30pm Jake in Progress* Brad Grey Television Productions / 20th Century Fox Television 10:00pm What About Brian Touchstone Television / Bad Robot 8:00pm According to Jim* Touchstone Television / Brad Grey 8:30pm Rodney* Touchstone Television TUE 9:00pm Commander-in-Chief Touchstone Television / Battle Plan Productions 10:00pm Boston Legal* 20th Century Fox Television / David E. Kelley Productions 8:00pm George Lopez* Warner Bros. Television / Mohawk Productions / Fortis Films 8:30pm Freddie Warner Bros. Television / Mohawk Productions / The Firm WED 9:00pm Lost* Touchstone Television / Bad Robot 10:00pm Invasion Warner Bros. -

The Expressive/Transformative Process of Violence Lee Mellor A

I Kill, Therefore I Am: The Expressive/Transformative Process of Violence Lee Mellor A Thesis In the Individualized Program Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Individualized Program) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada July 2018 ©Lee Mellor, 2018 !"#!"$%&'()#&*+$,&-.( ,!/""0("1(2$'%)'-+(,-)%&+,! This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Lee Mellor Entitled: I Kill, Therefore I Am: The Expressive Transformative Theory of Violence and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Individualized program (INDI)) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: "#$%&! '&(!"#$&)*+!,*%++! !-./*&0$)!-.$1%0*&! '&(!2$&%0$!34&45#%0+6%! !-./*&0$)!/4! 7&48&$1! '&(!9&*8!:%*)+*0! !-.$1%0*&! '&(!-&%5!;%56*<! !-.$1%0*&! '&(!=1<!3>%??*0! -.$1%0*&! !'&(!@%A*6!@*06$/*+#! B#*+%+!3CD*&A%+4&! '&(!E*$0F,45#!G$C&*05*! =DD&4A*H!I<! '&(!,$5#*)!J*&8*&K(9&$HC$/*!7&48&$1!'%&*5/4&! !'*5*1I*&!LK!MNOP! '&(!7$C)$!Q44HF=H$1+K!'*$0! !35#44)!4?!9&$HC$/*!3/CH%*+ Abstract I Kill, Therefore I Am: The Expressive/Transformative Process of Violence Lee Mellor, Ph.D. Concordia University, 2018 Before the late-Industrial age, a minority of murderers posed their victims’ corpses to convey a message. With the rise of mass media, such offenders also began sending verbal communications to journalists and the authorities. Unsurprisingly, the 21st century has seen alienated killers promote their violent actions and homicidal identities through online communications: from VLOGs to manifestos, even videos depicting murder and corpse mutilation. -

QX London Gay History

QX 596 MASTER PT.1 24/7/06 12:07 pm Page 10 qx FEATURE Eros On Piccadilly - so named after the Greek god of love because it was notoriously surrounded by hookers Soho Square in 1816 Starting this week, QX traces the history of London’s gay ghettos - North, South, East, West and Central. This week... WESTWhat’s made Central London such a magnetEND for gay men for 300 years?BOYS HAYDON BRIDGE reveals all… IF you’re not doing anything one Sunday, you Lane, Holborn, was raided in 1726. (Although www.pinkuk.com and a recent posting reads, can take a tour of historic gay Soho courtesy of this area was swept away long ago, it’s now “I’m a Special for the Royal Parks Unit for the Kairos. But it’s a bit of a cheat. Although today occupied by the London School of Economics, Metropolitan Police. We only visit the cruising it’s camper than Jordan’s and Cheryl Tweedy’s which hosts the gay Latino club Exilio). area to deter the criminals. If you get robbed, weddings put together, Soho has been gay for Prosecutions, and indeed executions, of gay please report it. We will be discreet and you only twenty years. The surrounding vicinity, men did little to deter others. In A View of will be treated sensitively.” however, is another matter. British gay life as Society and Manners in High and Low Life Historian Matt Cook says that it was the con- we know it began in London’s West End 300 (1781), writer George Parker deplored the struction of the railways, from 1837 to 1876, years ago, and virtually every significant event men “who signal to each other in St James’ that brought about the next advance in gay in British gay history ever since has occurred Park, and then retire to satisfy a passion too society.