CBD Fifth National Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Community Integrated Management Plan Palauli East, Savaii

Community Integrated Management Plan Palauli East, Savaii Implementation Guidelines 2018 COMMUNITY INTEGRATED MANAGEMENT PLAN IMPLEMENTATION GUIDELINES Foreword It is with great pleasure that I present the new Community Integrated Management (CIM) Plans, formerly known as Coastal Infrastructure Management (CIM) Plans. The revised CIM Plans recognizes the change in approach since the first set of fifteen CIM Plans were developed from 2002-2003 under the World Bank funded Infrastructure Asset Management Project (IAMP) , and from 2004-2007 for the remaining 26 districts, under the Samoa Infrastructure Asset Management (SIAM) Project. With a broader geographic scope well beyond the coastal environment, the revised CIM Plans now cover all areas from the ridge-to-reef, and includes the thematic areas of not only infrastructure, but also the environment and biological resources, as well as livelihood sources and governance. The CIM Strategy, from which the CIM Plans were derived from, was revised in August 2015 to reflect the new expanded approach and it emphasizes the whole of government approach for planning and implementation, taking into consideration an integrated ecosystem based adaptation approach and the ridge to reef concept. The timeframe for implementation and review has also expanded from five years to ten years as most of the solutions proposed in the CIM Plan may take several years to realize. The CIM Plan is envisaged as the blueprint for climate change interventions across all development sectors – reflecting the programmatic approach to climate change adaptation taken by the Government of Samoa. The proposed interventions outlined in the CIM Plans are also linked to the Strategy for the Development of Samoa 2016/17 – 2019/20 and the relevant ministry sector plans. -

Faleata East - Upolu

Community Integrated Management Plan Faleata East - Upolu Implementation Guidelines 2018 COMMUNITY INTEGRATED MANAGEMENT PLAN IMPLEMENTATION GUIDELINES Foreword It is with great pleasure that I present the new Community Integrated Management (CIM) Plans, formerly known as Coastal Infrastructure Management (CIM) Plans. The revised CIM Plans recognizes the change in approach since the first set of fifteen CIM Plans were developed from 2002-2003 under the World Bank funded Infrastructure Asset Management Project (IAMP) , and from 2004-2007 for the remaining 26 districts, under the Samoa Infrastructure Asset Management (SIAM) Project. With a broader geographic scope well beyond the coastal environment, the revised CIM Plans now cover all areas from the ridge-to-reef, and includes the thematic areas of not only infrastructure, but also the environment and biological resources, as well as livelihood sources and governance. The CIM Strategy, from which the CIM Plans were derived from, was revised in August 2015 to reflect the new expanded approach and it emphasizes the whole of government approach for planning and implementation, taking into consideration an integrated ecosystem based adaptation approach and the ridge to reef concept. The timeframe for implementation and review has also expanded from five years to ten years as most of the solutions proposed in the CIM Plan may take several years to realize. The CIM Plans is envisaged as the blueprint for climate change interventions across all development sectors – reflecting the programmatic approach to climate resilience adaptation taken by the Government of Samoa. The proposed interventions outlined in the CIM Plans are also linked to the Strategy for the Development of Samoa 2016/17 – 2019/20 and the relevant ministry sector plans. -

The Archaeology of Lapita Dispersal in Oceania

The archaeology of Lapita dispersal in Oceania pers from the Fourth Lapita Conference, June 2000, Canberra, Australia / Terra Australis reports the results of archaeological and related research within the south and east of Asia, though mainly Australia, New Guinea and Island Melanesia — lands that remained terra australis incognita to generations of prehistorians. Its subject is the settlement of the diverse environments in this isolated quarter of the globe by peoples who have maintained their discrete and traditional ways of life into the recent recorded or remembered past and at times into the observable present. Since the beginning of the series, the basic colour on the spine and cover has distinguished the regional distribution of topics, as follows: ochre for Australia, green for New Guinea, red for Southeast Asia and blue for the Pacific islands. From 2001, issues with a gold spine will include conference proceedings, edited papers, and monographs which in topic or desired format do not fit easily within the original arrangements. All volumes are numbered within the same series. List of volumes in Terra Australis Volume 1: Burrill Lake and Currarong: coastal sites in southern New South Wales. R.J. Lampert (1971) Volume 2: Ol Tumbuna: archaeological excavations in the eastern central Highlands, Papua New Guinea. J.P. White (1972) Volume 3: New Guinea Stone Age Trade: the geography and ecology of traffic in the interior. I. Hughes (1977) Volume 4: Recent Prehistory in Southeast Papua. B. Egloff (1979) Volume 5: The Great Kartan Mystery. R. Lampert (1981) Volume 6: Early Man in North Queensland: art and archeaology in the Laura area. -

Enhancing Safety, Security and Sustainability of Apia Port: Due

Due Diligence Report Project Number: 47358-002 May 2019 SAM: Enhancing Safety, Security and Sustainability of Apia Port Project (Grant xxxx) Prepared by the Samoa Ports Authority for the Asian Development Bank. This due diligence report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgements as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Enhancing Safety, Security and Sustainability of Apia Port – Social and Poverty Assessment Report CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 4 April 2016) Tala – Samoan Tala (SAT) = $1.00 = ABBREVIATIONS ADB - Asian Development Bank AUA - Apia Urban Area DDR - Due Diligence Report EA - Executing Agency EMP - Environmental Management Plan EPA - Environmental Protection Agency GOS - Government of the Samoa GRM - Grievance Redress Mechanism HIES - Household Income and Expenditures Survey IA - Implementing Agency IP - Indigenous People IR - Involuntary Resettlement MNRE - Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment MOF - Ministry of Finance MOR - Ministry of Revenue PIC - Pacific Island Countries PUMA - Planning and Urban Management Authority RP - Resettlement Plan SPA - Samoa Ports Authority -

O Tiafau O Le Malae O Le Fa'autugatagi a Samoa

O TIAFAU O LE MALAE O LE FA’AUTUGATAGI A SAMOA: A STUDY OF THE IMPACT OF THE LAND AND TITLES COURT’S DECISIONS OVER CUSTOMARY LAND AND FAMILY TITLES by Telea Kamu Tapuai Potogi A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Copyright © 2014 by Telea Kamu Tapuai Potogi School of Social Sciences Faculty of Arts, Law & Education The University of the South Pacific August 2014 DECLARATION I, Telea Kamu Tapuai Potogi, declare that this thesis is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge, it contains no material previously published, or substantially overlapping with material submitted for the award of any other degree at any institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the text. Signature……………………………………………..Date…………………………….. Name …………………………………………………………………………………... Student ID No. ………………………………………………………………………… The research in this thesis was performed under my supervision and to my knowledge is the sole work of Mr. Telea Kamu Tapuai Potogi. Signature……………………………………………..Date…………………………….. Name …………………………………………………………………………………... Designation ……….…………………………………………………………………… Upu Tomua Le Atua Silisili ese, fa’afetai ua e apelepelea i matou i ou aao alofa, ua le afea i matou e se atua folau o le ala. O le fa’afetai o le fiafia aua ua gase le tausaga, ua mou atu fo’i peau lagavale ma atua folau sa lamatia le faigamalaga. O lenei ua tini pao le uto pei o le faiva i vai. Mua ia mua o ma fa’asao i le Atua o le Mataisau o le poto ma le atamai. O Lona agalelei, o le alofa le fa’atuaoia ma le pule fa’asoasoa ua mafai ai ona taulau o lenei fa’amoemoe. -

51268-001: Central Cross Island Road Upgrading Project

DRAFT Resettlement Plan March 2020 SAM: Central Cross Island Road Upgrading Project (CCIRUP) Prepared by the Land Transport Authority of Samoa for the Asian Development Bank. i CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 02 September 2019) Currency unit – Samoan Tala (WST) WST1.00 = $ 0.37 $1.00 = WST 2.69 ABBREVIATIONS AP – affected persons AoG – Assemblies of God CCCS – Congregational Church of Samoa CCIR – Central Cross Island Road CCIRUP – Central Cross Island Road Upgrading Project (the Project) COEP – codes of environmental practice ERAP – Enhanced Road Access Project ESIA – environmental and social impact assessment GCLS - Grievance Complaint Logging System LDS – Latter Day Saints LTA – Land Transport Authority MNRE – Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment MOF – Ministry of Finance MWCSD – Ministry of Women, Community and Social Development OHS – occupational health and safety PMU – project management unit PUMA – Planning and Urban Management Division of MWTI RC – roman catholic RP – resettlement plan TCE – Tropical Cyclone Evan WST – Samoan Tala WEIGHTS AND MEASURES km (kilometer) – length relevant to road m (meter) – Length or width relevant to road vpd (vehicles per day) – traffic volume NOTES In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. This resettlement plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of the Asian Development Bank (ADB)'s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of the ADB website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the ADB does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. -

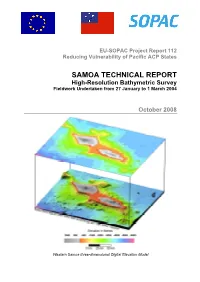

High-Resolution Bathymetric Survey of Samoa

EU-SOPAC Project Report 112 Reducing Vulnerability of Pacific ACP States SAMOA TECHNICAL REPORT High-Resolution Bathymetric Survey Fieldwork Undertaken from 27 January to 1 March 2004 October 2008 Western Samoa three-dimensional Digital Elevation Model Prepared by: Jens Krüger and Salesh Kumar SOPAC Secretariat May 2008 PACIFIC ISLANDS APPLIED GEOSCIENCE COMMISSION c/o SOPAC Secretariat Private Mail Bag GPO, Suva FIJI ISLANDS http://www.sopac.org Phone: +679 338 1377 Fax: +679 337 0040 www.sopac.org [email protected] Important Notice This report has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Community; however, the views expressed herein must never be taken to reflect the official opinion of the European Community. Samoa: High-Resolution Bathymetry EU EDF-SOPAC Reducing Vulnerability of Pacific ACP States – iii TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... 1 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 2 1.1 Background ................................................................................................................ 2 1.2 Geographic Situation .................................................................................................. 2 1.3 Geological Setting ...................................................................................................... 3 1.4 Previous Bathymetry Compilations............................................................................ -

Savai'i Volcano

A Visitor’s Field Guide to Savai’i – Touring Savai’i with a Geologist A Visitor's Field Guide to Savai’i Touring Savai'i with a Geologist Warren Jopling Page 1 A Visitor’s Field Guide to Savai’i – Touring Savai’i with a Geologist ABOUT THE AUTHOR AND THIS ARTICLE Tuapou Warren Jopling is an Australian geologist who retired to Savai'i to grow coffee after a career in oil exploration in Australia, Canada, Brazil and Indonesia. Travels through Central America, the Andes and Iceland followed by 17 years in Indonesia gave him a good understanding of volcanology, a boon to later educational tourism when explaining Savai'i to overseas visitors and student groups. His 2014 report on Samoa's Geological History was published in booklet form by the Samoa Tourism Authority as a Visitor's Guide - a guide summarising the main geological events that built the islands but with little coverage of individual natural attractions. This present article is an abridgement of the 2014 report and focuses on Savai'i. It is in three sections; an explanation of plate movement and hotspot activity for visitors unfamiliar with plate tectonics; a brief summary of Savai'i's geological history then an island tour with some geologic input when describing the main sites. It is for nature lovers who would appreciate some background to sightseeing. Page 1 A Visitor’s Field Guide to Savai’i – Touring Savai’i with a Geologist The Pacific Plate, The Samoan Hotspot, The Samoan Archipelago The Pacific Plate, the largest of the Earth's 16 major plates, is born along the East Pacific Rise. -

CURRICULUM VITAE (September 2011)

CURRICULUM VITAE (September 2011) David William Steadman Present Positions and Address: Curator of Ornithology; Associate Director for Collections and Research Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida, P. O. Box 117800, Gainesville, FL 32611. Telephone (352) 273-1969; Fax (352) 846-0287; E-mail, [email protected] Primary Research Interests: Ornithology, zooarchaeology, and vertebrate paleontology of tropical and subtropical regions. Extinction, systematics, and historic biogeography of birds on Caribbean and Pacific islands. Paleontology, biogeography, evolution, and community ecology of New World landbirds. Education: Ph.D. Geosciences, University of Arizona, 1982 M.S. Zoology, University of Florida, 1975 B.S. Biology, Edinboro State College, 1973 Recent Employment History: August 2001 – June 2004, August 2007 – present: Assistant/Associate Director for Collections and Research, Florida Museum of Natural History March 2000 – February 2003: University of Florida Research Foundation Professor August 1995 – present: Assistant/Associate/Full Curator of Ornithology, Florida Museum of Natural History February 1985 – July 1995: Associate and Senior Scientist (Zoology), and Curator of Vertebrates, New York State Museum Research Grants: August 2011 (ongoing) Collaborative Research: Long-term Dynamics and Resilience of Terrrestrial Plant and Animal Communities in the Bahamas. National Science Foundation (J. Franklin, DWS, P.L. Fall; total award $414,000; UF portion $164,573). August 2011 (ongoing) U.S.-Peru Planning Visit: Planning a Collaborative Program of Vertebrate Paleontology in Northwestern Peru. $21,296. National Science Foundation. November 2009 (ongoing) Logistical and Intellectual Foundation for Teaching Field Courses in the Bahamas and Turks & Caicos Islands. $22,168. Faculty Enhancement Opportunity Award, Provost’s Office, University of Florida. -

Stevensoniana; an Anecdotal Life and Appreciation of Robert Louis Stevenson, Ed. from the Writings of J.M. Barrie, S.R. Crocket

——; — ! 92 STEVENSONIANA VIII ISLAND DAYS TO TUSITALA IN VAILIMA^ Clearest voice in Britain's chorus, Tusitala Years ago, years four-and-twenty. Grey the cloudland drifted o'er us, When these ears first heard you talking, When these eyes first saw you smiling. Years of famine, years of plenty, Years of beckoning and beguiling. Years of yielding, shifting, baulking, ' When the good ship Clansman ' bore us Round the spits of Tobermory, Glens of Voulin like a vision. Crags of Knoidart, huge and hoary, We had laughed in light derision. Had they told us, told the daring Tusitala, What the years' pale hands were bearing, Years in stately dim division. II Now the skies are pure above you, Tusitala; Feather'd trees bow down to love you 1 This poem, addressed to Robert Louis Stevenson, reached him at Vailima three days before his death. It was the last piece of verse read by Stevenson, and it is the subject of the last letter he wrote on the last day of his life. The poem was read by Mr. Lloyd Osbourne at the funeral. It is here printed, by kind permission of the author, from Mr. Edmund Gosse's ' In Russet and Silver,' 1894, of which it was the dedication. After the Photo by] [./. Davis, Apia, Samoa STEVENSON AT VAILIMA [To face page i>'l ! ——— ! ISLAND DAYS 93 Perfum'd winds from shining waters Stir the sanguine-leav'd hibiscus That your kingdom's dusk-ey'd daughters Weave about their shining tresses ; Dew-fed guavas drop their viscous Honey at the sun's caresses, Where eternal summer blesses Your ethereal musky highlands ; Ah ! but does your heart remember, Tusitala, Westward in our Scotch September, Blue against the pale sun's ember, That low rim of faint long islands. -

Samoa Socio-Economic Atlas 2011

SAMOA SOCIO-ECONOMIC ATLAS 2011 Copyright (c) Samoa Bureau of Statistics (SBS) 2011 CONTACTS Telephone: (685) 62000/21373 Samoa Socio Economic ATLAS 2011 Facsimile: (685) 24675 Email: [email protected] by Website: www.sbs.gov.ws Postal Address: Samoa Bureau of Statistics The Census-Surveys and Demography Division of Samoa Bureau of Statistics (SBS) PO BOX 1151 Apia Samoa National University of Samoa Library CIP entry Samoa socio economic ATLAS 2011 / by The Census-Surveys and Demography Division of Samoa Bureau of Statistics (SBS). -- Apia, Samoa : Samoa Bureau of Statistics, Government of Samoa, 2011. 76 p. : ill. ; 29 cm. Disclaimer: This publication is a product of the Division of Census-Surveys & Demography, ISBN 978 982 9003 66 9 Samoa Bureau of Statistics. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions 1. Census districts – Samoa – maps. 2. Election districts – Samoa – expressed in this volume do not necessarily reflect the views of any funding or census. 3. Election districts – Samoa – statistics. 4. Samoa – census. technical agencies involved in the census. The boundaries and other information I. Census-Surveys and Demography Division of SBS. shown on the maps are only imaginary census boundaries but do not imply any legal status of traditional village and district boundaries. Sam 912.9614 Sam DDC 22. Published by The Samoa Bureau of Statistics, Govt. of Samoa, Apia, Samoa, 2015. Overview Map SAMOA 1 Table of Contents Map 3.4: Tertiary level qualification (Post-secondary certificate, diploma, Overview Map ................................................................................................... 1 degree/higher) by district, 2011 ................................................................... 26 Introduction ...................................................................................................... 3 Map 3.5: Population 15 years and over with knowledge in traditional tattooing by district, 2011 ........................................................................... -

Leading the Recovery of Two of Samoa's Most Threatened Bird

LEADING THE RECOVERY OF TWO OF SAMOA’S MOST THREATENED BIRD SPECIES the tooth-billed pigeon (Manumea) and the mao (Ma’oma’o) through ecological research to identify current threats BIODI VERSITY CO NSERVATION LESSONS LEARNED TECHNICAL SERIES 25 BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION LESSONS LEARNED TECHNICAL SERIES Leading the recovery of two of Samoa’s most threatened bird species, the tooth-billed pigeon (Manumea) and the mao (Ma’oma’o) 25 through ecological research to identify current threats Biodiversity Conservation Lessons Learned Technical Series is published by: Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) and Conservation International Pacific Islands and Oceans Program (CI-Pacific) PO Box 2035, Apia, Samoa T: + 685 21593 E: [email protected] W: www.conservation.org The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan, the MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank. A fundamental goal is to ensure civil society is engaged in biodiversity conservation. Conservation International Pacific Islands and Oceans Program. 2013. Biodiversity Conservation Lessons Learned Technical Series 25: Leading the recovery of two of Samoa’s most threatened bird species, the tooth-billed pigeon (Manumea) and the mao (Ma’oma’o) through ecological research to identify current threats. Conservation International, Apia, Samoa Authors: David Butler, Rebecca Stirnemann Design/Production: Joanne Aitken, The Little Design Company, www.thelittledesigncompany.com Cover Photograph: © Rebecca Stirnemann Series Editor: Leilani Duffy, Conservation International Pacific Islands and Oceans Program Conservation International is a private, non-profit organization exempt from federal income tax under section 501c(3) of the Internal Revenue Code.