Haltwhistle : an Archaeological Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Map for Day out One Hadrian's Wall Classic

Welcome to Hadian’s Wall Country a UNESCO Arriva & Stagecoach KEY Map for Day Out One World Heritage Site. Truly immerse yourself in Newcastle - Hexham - Carlisle www.arrivabus.co.uk/north-east A Runs Daily the history and heritage of the area by exploring 685 Hadrian’s Wall Classic Tickets and Passes National Trail (See overleaf) by bus and on foot. Plus, spending just one day Arriva Cuddy’s Crags Newcastle - Corbridge - Hexham www.arrivabus.co.uk/north-east Alternative - Roman Traveller’s Guide without your car can help to look after this area of X85 Runs Monday - Friday Military Way (Nov-Mar) national heritage. Hotbank Crags 3 AD122 Rover Tickets The Sill Walk In this guide to estbound These tickets offer This traveller’s guide is designed to help you leave Milecastle 37 Housesteads eet W unlimited travel on Parking est End een Hadrian’s Wall uns r the AD122 service. Roman Fort the confines of your car behind and truly “walk G ee T ont Str ough , Hexham Road Approx Refreshments in the footsteps of the Romans”. So, find your , Lion and Lamb journey times Crag Lough independent spirit and let the journey become part ockley don Mill, Bowes Hotel eenhead, Bypass arwick Bridge Eldon SquaLemingtonre Thr Road EndsHeddon, ThHorsler y Ovington Corbridge,Road EndHexham Angel InnHaydon Bridge,Bar W Melkridge,Haltwhistle, The Gr MarketBrampton, Place W Fr Scotby Carlisle Adult Child Concession Family Roman Site Milecastle 38 Country Both 685 and X85 of your adventure. hr Sycamore 685 only 1 Day Ticket £12.50 £6.50 £9.50 £26.00 Haydon t 16 23 27 -

Tyne Estuary Partnership Report FINAL3

Tyne Estuary Partnership Feasibility Study Date GWK, Hull and EA logos CONTENTS CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... 2 PART 1: INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 6 Structure of the Report ...................................................................................................... 6 Background ....................................................................................................................... 7 Vision .............................................................................................................................. 11 Aims and Objectives ........................................................................................................ 11 The Partnership ............................................................................................................... 13 Methodology .................................................................................................................... 14 PART 2: STRATEGIC CONTEXT ....................................................................................... 18 Understanding the River .................................................................................................. 18 Landscape Character ...................................................................................................... 19 Landscape History .......................................................................................................... -

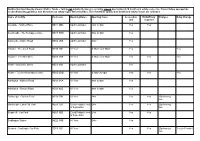

Public Toilet Map NCC Website

Northumberland County Council Public Tolets - Toilets not detailed below are currently closed due to Covid-19 health and safety concerns. Please follow appropriate social distancing guidance and directions on safety signs at the facilities. This list will be updated as health and safety issues are reviewed. Name of facility Postcode Opening Dates Opening times Accessible RADAR key Charges Baby Change unit required Allendale - Market Place NE47 9BD April to October 7am to 4pm Yes Yes Allenheads - The Heritage Centre NE47 9HN April to October 7am to 4pm Yes Alnmouth - Marine Road NE66 2RZ April to October 24hr Yes Alnwick - Greenwell Road NE66 1SF All Year 6:30am to 6:30pm Yes Yes Alnwick - The Shambles NE66 1SS All Year 6:30am to 6:30pm Yes Yes Yes Amble - Broomhill Street NE65 0AN April to October Yes Amble - Tourist Information Centre NE65 0DQ All Year 6:30am to 6pm Yes Yes Yes Ashington - Milburn Road NE63 0NA All Year 8am to 4pm Yes Ashington - Station Road NE63 9UZ All Year 8am to 4pm Yes Bamburgh - Church Street NE69 7BN All Year 24hr Yes Yes 20p honesty box Bamburgh - Links Car Park NE69 7DF Good Friday to end 24hr Yes Yes 20p honesty of September box Beadnell - Car Park NE67 5EE Good Friday to end 24hr Yes Yes of September Bedlington Station NE22 5HB All Year 24hr Yes Berwick - Castlegate Car Park TD15 1JS All Year Yes Yes 20p honesty Yes (in Female) box Northumberland County Council Public Tolets - Toilets not detailed below are currently closed due to Covid-19 health and safety concerns. -

Trains Tyne Valley Line

From 15th May to 2nd October 2016 Newcastle - Hexham - Carlisle Northern Mondays to Fridays Gc¶ Hp Mb Mb Mb Mb Gc¶ Mb Sunderland dep … … 0730 0755 0830 … 0930 … … 1030 1130 … 1230 … 1330 Newcastle dep 0625 0646 0753 0824 0854 0924 0954 1024 1054 1122 1154 1222 1254 1323 1354 Dunston 0758 0859 Metrocentre 0634 0654 0802 0832 0903 0932 1002 1033 1102 1132 1202 1232 1302 1333 1402 Blaydon 0639 | 0806 | 1006 | | 1206 | | 1406 Wylam 0645 0812 0840 0911 1012 1110 1212 1310 1412 Prudhoe 0649 0704 0817 0844 0915 0942 1017 1043 1114 1142 1217 1242 1314 1344 1417 Stocksfield 0654 | 0821 0849 0920 | 1021 | 1119 | 1221 | 1319 | 1421 Riding Mill 0658 | 0826 | 0924 | 1026 | 1123 | 1226 | 1323 | 1426 Corbridge 0702 0830 0928 1030 1127 1230 1327 1430 Hexham arr 0710 0717 0838 0858 0937 0955 1038 1055 1137 1155 1238 1255 1337 1356 1438 Hexham dep … 0717 … 0858 … 0955 … 1055 … 1155 … 1255 … 1357 … Haydon Bridge … 0726 … 0907 … | … 1104 … | … 1304 … | … Bardon Mill … 0733 … 0914 … … 1111 … … 1311 … … Haltwhistle … 0740 … 0921 … 1014 … 1118 … 1214 … 1318 … 1416 … Brampton … 0755 … 0936 … | … 1133 … | … 1333 … | … Wetheral … 0804 … 0946 … … 1142 … … 1342 … … Carlisle arr … 0815 … 0957 … 1046 … 1157 … 1247 … 1354 … 1448 … Mb Mb Wv Mb Gc¶ Mb Ct Mb Sunderland dep … 1430 … 1531 … 1630 … … 1730 … 1843 1929 2039 2211 Newcastle dep 1424 1454 1524 1554 1622 1654 1716 1724 1754 1824 1925 2016 2118 2235 Dunston 1829 Metrocentre 1432 1502 1532 1602 1632 1702 1724 1732 1802 1833 1934 2024 2126 2243 Blaydon | | 1606 -

Sunderland - Newcastle - Hexham - Carlisle Sundays

Sunderland - Newcastle - Hexham - Carlisle Sundays Middlesbrough d - - 0832 - - 0931 - - 1031 - Hartlepool d - - 0903 - - 1001 - - 1101 - Horden d - - 0914 - - 1012 - - 1112 - Sunderland d - - 0932 - - 1030 - - 1130 - Newcastle a - - 0951 - - 1050 - - 1150 - d 0845 0930 0955 1016 1035 1055 1115 1133 1155 1215 Dunston - 0935 - 1021 - - 1121 - - 1220 MetroCentre a 0852 0939 1002 1025 1043 1102 1124 1141 1202 1224 d 0853 - 1003 - - 1103 - - 1203 - Blaydon 0857 - 1007 - - - - - 1207 - Wylam 0903 - 1013 - - 1111 - - 1213 - Prudhoe 0908 - 1017 - - 1115 - - 1218 - Stocksfield 0912 - 1022 - - 1120 - - 1222 - Riding Mill 0917 - 1026 - - 1124 - - 1227 - Corbridge 0921 - 1030 - - 1128 - - 1231 - Hexham a 0927 - 1036 - - 1134 - - 1237 - d 0927 - 1037 - - 1135 - - 1237 - Haydon Bridge 0937 - 1046 - - 1144 - - - - Bardon Mill 0943 - 1052 - - 1150 - - - - Haltwhistle 0950 - 1100 - - 1158 - - 1256 - Brampton 1005 - 1115 - - - - - 1311 - Wetheral 1014 - 1124 - - - - - 1320 - Carlisle a 1024 - 1134 - - 1232 - - 1330 - Middlesbrough d - 1131 - - 1230 - - 1331 - - Hartlepool d - 1201 - - 1300 - - 1401 - - Horden d - 1212 - - 1311 - - 1412 - - Sunderland d - 1230 - - 1329 - - 1430 - - Newcastle a - 1250 - - 1349 - - 1450 - - d 1235 1255 1315 1333 1355 1415 1428 1455 1515 1535 Dunston - - 1321 - - 1420 - - 1521 - MetroCentre a 1243 1302 1324 1341 1402 1424 1436 1502 1524 1543 d - 1303 - - 1403 - - 1503 - - Blaydon - - - - 1407 - - - - - Wylam - 1311 - - 1413 - - 1511 - - Prudhoe - 1315 - - 1418 - - 1515 - - Stocksfield - 1320 - - 1422 - - 1520 - - Riding Mill -

Der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr

26 . 3 . 84 Amtsblatt der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr . L 82 / 67 RICHTLINIE DES RATES vom 28 . Februar 1984 betreffend das Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten landwirtschaftlichen Gebiete im Sinne der Richtlinie 75 /268 / EWG ( Vereinigtes Königreich ) ( 84 / 169 / EWG ) DER RAT DER EUROPAISCHEN GEMEINSCHAFTEN — Folgende Indexzahlen über schwach ertragsfähige Böden gemäß Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe a ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden bei der Bestimmung gestützt auf den Vertrag zur Gründung der Euro jeder der betreffenden Zonen zugrunde gelegt : über päischen Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft , 70 % liegender Anteil des Grünlandes an der landwirt schaftlichen Nutzfläche , Besatzdichte unter 1 Groß vieheinheit ( GVE ) je Hektar Futterfläche und nicht über gestützt auf die Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG des Rates vom 65 % des nationalen Durchschnitts liegende Pachten . 28 . April 1975 über die Landwirtschaft in Berggebieten und in bestimmten benachteiligten Gebieten ( J ), zuletzt geändert durch die Richtlinie 82 / 786 / EWG ( 2 ), insbe Die deutlich hinter dem Durchschnitt zurückbleibenden sondere auf Artikel 2 Absatz 2 , Wirtschaftsergebnisse der Betriebe im Sinne von Arti kel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe b ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden durch die Tatsache belegt , daß das auf Vorschlag der Kommission , Arbeitseinkommen 80 % des nationalen Durchschnitts nicht übersteigt . nach Stellungnahme des Europäischen Parlaments ( 3 ), Zur Feststellung der in Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe c ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG genannten geringen Bevöl in Erwägung nachstehender Gründe : kerungsdichte wurde die Tatsache zugrunde gelegt, daß die Bevölkerungsdichte unter Ausschluß der Bevölke In der Richtlinie 75 / 276 / EWG ( 4 ) werden die Gebiete rung von Städten und Industriegebieten nicht über 55 Einwohner je qkm liegt ; die entsprechenden Durch des Vereinigten Königreichs bezeichnet , die in dem schnittszahlen für das Vereinigte Königreich und die Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten Gebiete Gemeinschaft liegen bei 229 beziehungsweise 163 . -

Archaeology in Northumberland Friends

100 95 75 Archaeology 25 5 in 0 Northumberland 100 95 75 25 5 0 Volume 20 Contents 100 100 Foreword............................................... 1 95 Breaking News.......................................... 1 95 Archaeology in Northumberland Friends . 2 75 What is a QR code?...................................... 2 75 Twizel Bridge: Flodden 1513.com............................ 3 The RAMP Project: Rock Art goes Mobile . 4 25 Heiferlaw, Alnwick: Zero Station............................. 6 25 Northumberland Coast AONB Lime Kiln Survey. 8 5 Ecology and the Heritage Asset: Bats in the Belfry . 11 5 0 Surveying Steel Rigg.....................................12 0 Marygate, Berwick-upon-Tweed: Kilns, Sewerage and Gardening . 14 Debdon, Rothbury: Cairnfield...............................16 Northumberland’s Drove Roads.............................17 Barmoor Castle .........................................18 Excavations at High Rochester: Bremenium Roman Fort . 20 1 Ford Parish: a New Saxon Cemetery ........................22 Duddo Stones ..........................................24 Flodden 1513: Excavations at Flodden Hill . 26 Berwick-upon-Tweed: New Homes for CAAG . 28 Remapping Hadrian’s Wall ................................29 What is an Ecomuseum?..................................30 Frankham Farm, Newbrough: building survey record . 32 Spittal Point: Berwick-upon-Tweed’s Military and Industrial Past . 34 Portable Antiquities in Northumberland 2010 . 36 Berwick-upon-Tweed: Year 1 Historic Area Improvement Scheme. 38 Dues Hill Farm: flint finds..................................39 -

Northumberland National Park Geodiversity Audit and Action Plan Location Map for the District Described in This Book

Northumberland National Park Geodiversity Audit and Action Plan Location map for the district described in this book AA68 68 Duns A6105 Tweed Berwick R A6112 upon Tweed A697 Lauder A1 Northumberland Coast A698 Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Holy SCOTLAND ColdstreamColdstream Island Farne B6525 Islands A6089 Galashiels Kelso BamburghBa MelrMelroseose MillfieldMilfield Seahouses Kirk A699 B6351 Selkirk A68 YYetholmetholm B6348 A698 Wooler B6401 R Teviot JedburghJedburgh Craster A1 A68 A698 Ingram A697 R Aln A7 Hawick Northumberland NP Alnwick A6088 Alnmouth A1068 Carter Bar Alwinton t Amble ue A68 q Rothbury o C B6357 NP National R B6341 A1068 Kielder OtterburOtterburnn A1 Elsdon Kielder KielderBorder Reservoir Park ForForestWaterest Falstone Ashington Parkand FtForest Kirkwhelpington MorpethMth Park Bellingham R Wansbeck Blyth B6320 A696 Bedlington A68 A193 A1 Newcastle International Airport Ponteland A19 B6318 ChollerforChollerfordd Pennine Way A6079 B6318 NEWCASTLE Once Housesteads B6318 Gilsland Walltown BrewedBrewed Haydon A69 UPON TYNE Birdoswald NP Vindolanda Bridge A69 Wallsend Haltwhistle Corbridge Wylam Ryton yne R TTyne Brampton Hexham A695 A695 Prudhoe Gateshead A1 AA689689 A194(M) A69 A686 Washington Allendale Derwent A692 A6076 TTownown A693 A1(M) A689 ReservoirReservoir Stanley A694 Consett ChesterChester-- le-Streetle-Street Alston B6278 Lanchester Key A68 A6 Allenheads ear District boundary ■■■■■■ Course of Hadrian’s Wall and National Trail N Durham R WWear NP National Park Centre Pennine Way National Trail B6302 North Pennines Stanhope A167 A1(M) A690 National boundaryA686 Otterburn Training Area ArAreaea of 0 8 kilometres Outstanding A689 Tow Law 0 5 miles Natural Beauty Spennymoor A688 CrookCrook M6 Penrith This product includes mapping data licensed from Ordnance Survey © Crown copyright and/or database right 2007. -

Walk to Wellbeing 2011

PleaSe nOte: Walk to Wellbeing What is it ? a walk to wellbeing is: • the walks and shared transport are A programme of 19 walks specially • free free selected by experienced health walk • sociable & fun • each walk has details about the leaders to introduce you to the superb • something most people can easily do terrain to help you decide how landscape that makes Northumberland • situated in some of the most suitable it is for you. the full route National Park so special. inspirational and tranquil landscape in Walk to Wellbeing 2011 England can be viewed on Walk4life Is it for me? Get out and get healthy in northumberland national Park website If you already join health walks and would • Refreshments are not provided as like to try walking a bit further in beautiful Some useful websites: part of the walk. countryside - Yes! To find out the latest news from • Meeting points along Hadrian’s Wall If you’ve never been on a health walk but Northumberland National Park: can be easily reached using the would like to try walking in a group, with a www.northumberlandnationalpark.org.uk leader who has chosen a route of around Hadrian’s Wall Bus (free with an For more information on your local over 60 pass) 4 miles which is not too challenging and full of interest -Yes! Walking For Health • Please wear clothing and footwear group:www.wfh.naturalengland.org.uk (preferably boots with a good grip) Regular walking can: For more information on West Tynedale appropriate for changeable weather • help weight management Healthy Life Scheme and other healthy and possible muddy conditions. -

2 Heather View, Plenmeller, Haltwhistle Ne49 0Hp

2 HEATHER VIEW, PLENMELLER, HALTWHISTLE NE49 0HP £575 per month, Unfurnished + £200 inc VAT tenancy paperwork and inventory fee other charges apply*. Rural location • 2 Reception rooms • 2 Bedrooms • Parking • Garden EPC Rating = E Council Tax = C A pretty, two bedroomed house set in a terrace of four, with views over open countryside. The property is located just off the A69 giving easy access to Carlisle, Hexham and Newcastle. Entrance Hallway with stairs to first floor, doors off to: Living Room – 4.2m x 4.2m A bright and spacious room with open fireplace and radiator. Window to the front of the property overlooking the garden. Dining Room/ Reception Two – 3.8m x 4.2m Solid fuel rayburn, double height built in cupboard, radiator and window to the rear. Passageway through to kitchen with understairs cupboard. Kitchen – 4.15m x 3.0m Shaker style units with rolltop work surface housing single sink and drainer. Space for electric cooker and under unit fridge. Plumbing for washing machine. Vinyl flooring, radiator and door to rear yard. Dual aspect windows. First Floor Bathroom – 3.4m x 3.1m Spacious bathroom with open shower/ wet area housing electric shower, bath, sink with mirror over, airing cupboard. Extractor fan. Separate WC Low level WC, window and vinyl flooring. Bedroom One – 3.3m x 4.5m Double room with built in cupboard and radiator. Bedroom Two – 5.4m x 4.2m Double room with two windows to the front of the property, radiator. Outside Front garden with path, mainly laid to lawn with plants and shrubs. -

English/French

World Heritage 36 COM WHC-12/36.COM/8D Paris, 1 June 2012 Original: English/French UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION CONVENTION CONCERNING THE PROTECTION OF THE WORLD CULTURAL AND NATURAL HERITAGE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE Thirty-sixth Session Saint Petersburg, Russian Federation 24 June – 6 July 2012 Item 8 of the Provisional Agenda: Establishment of the World Heritage List and of the List of World Heritage in Danger 8D: Clarifications of property boundaries and areas by States Parties in response to the Retrospective Inventory SUMMARY This document refers to the results of the Retrospective Inventory of nomination files of properties inscribed on the World Heritage List in the period 1978 - 1998. To date, seventy States Parties have responded to the letters sent following the review of the individual files, in order to clarify the original intention of their nominations (or to submit appropriate cartographic documentation) for two hundred fifty-three World Heritage properties. This document presents fifty-five boundary clarifications received from twenty-five States Parties, as an answer to the Retrospective Inventory. Draft Decision: 36 COM 8D, see Point IV I. The Retrospective Inventory 1. The Retrospective Inventory, an in-depth examination of the Nomination dossiers available at the World Heritage Centre, ICOMOS and IUCN, was initiated in 2004, in parallel with the launching of the Periodic Reporting exercise in Europe, involving European properties inscribed on the World Heritage List in the period 1978 - 1998. The same year, the Retrospective Inventory was endorsed by the World Heritage Committee at its 7th extraordinary session (UNESCO, 2004; see Decision 7 EXT.COM 7.1). -

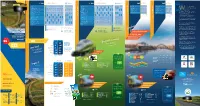

AD12-Timetable-20210412-11Be0e97.Pdf

SUMMER & AUTUMN WINTER SUMMER & AUTUMN WINTER ALL YEAR ALL YEAR AD122 every day of the week weekends AD122 every day of the week weekends 185 Mon to Sat 185 Mon to Sat X122 X122 185 185 185 185 185 185 Hexham bus station stand D 0835 0910 1010 1110 1210 1310 1410 1510 1610 1710 0910 1110 1410 1610 Milecastle Inn bus stop 0958 1048 1158 1248 1358 1448 1558 1648 1758 0958 1158 1448 1648 Haltwhistle railway station 0950 1130 1510 Birdoswald Roman fort car park 1022 1200 1545 elcome to route AD122 - the Hexham railway station 0913 1013 1113 1213 1313 1413 1513 1613 1713 0913 1113 1413 1613 Walltown Roman Army Museum 1054 1254 1454 1654 1804 1454 1654 Haltwhistle Market Place 0952 1132 1512 Gilsland Bridge hotel 1028 1206 1551 Hadrian’s Wall country bus, it’s the Chesters Roman fort main entrance 0925 1025 1125 1225 1325 1425 1525 1625 1725 0925 1125 1425 1625 Greenhead hotel q 1058 q 1258 q 1458 q 1658 1808 q q 1458 1658 Haltwhistle Park Road 0954 1134 1514 Greenhead hotel 1037 1215 1600 best way of getting out and about Housesteads Roman fort bus turning circle 0939 1039 1139 1239 1339 1439 1539 1639 1739 0939 1139 1439 1639 Herding Hill Farm campsite 0959 1159 1359 1559 0959 1159 Walltown Roman Army Museum 1002 1142 1522 Walltown Roman Army Museum 1041 1219 1604 across the region. The Sill National Landscape Discovery Centre 0944 1044 1144 1244 1344 1444 1544 1644 1744 0944 1144 1444 1644 Haltwhistle Market Place 0904 1004 q 1204 q 1404 q 1604 q q 1004 1204 q q Greenhead hotel 1006 1146 1526 Haltwhistle Park Road 1049 1227 1612 Hexham Vindolanda