The Statutes of Iona: Text and Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Paleolithic and Mesolithic Occupation of the Isle of Jura, Argyll

John MERCER, Edinburgh THE PALAEOLITHIC AND MESOLITHIC OCCUPATION OF THE ISLE OF JURA, ARGYLL, SCOTLAND The occupation sequence about to be described has been built up from a dozen sites concentrated in N-Jura (Mercer, 1968-79).It is based on local land-sea relationships, site stratification, pollen analysis, drifted-pumice dating and radiocarbon assay.The paper 1 will begin with a discussion of the inter-linked shorelines and climate, then give an impression of the main sites and, finally, describe and compare the stone implement typology. Late Glacial habitat 2017 Jura is a vast island (fig.1) some 80 km (50 m) long.It rises to about 780 m (2500ft) Biblioteca, in the south and 470 m (1500 ft)in the north. Several recent papers have shown that W-Scotland was suitable for human habita ULPGC. tion from 11,000 or 10,500 BC. Kirk and Godwin (1963) described an organic level por at Loch Drama (Ross and Cromarty) which, with a C14 date of 12,810 ± 155 be (Q-457), had not since been overlaid by ice, although in a through valley.Kirk com realizada mented: "In view of its location on the exposed, north-west Atlantic rim of Scotland one would except ...an onset of milder oceanic conditions at an earlier date than localities in the English Lowlands or the North European Plain." He concluded his Digitalización contribution: " ... it would appear that in Northern Scotland the process of degla ciation was not unlike that established for Scandinavia, namely an early and rapid autores. los melt of the ice in western fjords and a longer survival in uplands east of the Atlantic watershed.The significance of such a possibility for plant, animal and human coloni sation needs no stressing." documento, Del Coope (summarised in Pennington, 1974), working on beetle remains, noted that © early in Zone I (12,380-10,000 BC) there was a rapid rise in temperature, from less than 10° C as a July average to almost 17° C, though winters may have remained cold. -

2020 Cruise Directory Directory 2020 Cruise 2020 Cruise Directory M 18 C B Y 80 −−−−−−−−−−−−−−− 17 −−−−−−−−−−−−−−−

2020 MAIN Cover Artwork.qxp_Layout 1 07/03/2019 16:16 Page 1 2020 Hebridean Princess Cruise Calendar SPRING page CONTENTS March 2nd A Taste of the Lower Clyde 4 nights 22 European River Cruises on board MS Royal Crown 6th Firth of Clyde Explorer 4 nights 24 10th Historic Houses and Castles of the Clyde 7 nights 26 The Hebridean difference 3 Private charters 17 17th Inlets and Islands of Argyll 7 nights 28 24th Highland and Island Discovery 7 nights 30 Genuinely fully-inclusive cruising 4-5 Belmond Royal Scotsman 17 31st Flavours of the Hebrides 7 nights 32 Discovering more with Scottish islands A-Z 18-21 Hebridean’s exceptional crew 6-7 April 7th Easter Explorer 7 nights 34 Cruise itineraries 22-97 Life on board 8-9 14th Springtime Surprise 7 nights 36 Cabins 98-107 21st Idyllic Outer Isles 7 nights 38 Dining and cuisine 10-11 28th Footloose through the Inner Sound 7 nights 40 Smooth start to your cruise 108-109 2020 Cruise DireCTOrY Going ashore 12-13 On board A-Z 111 May 5th Glorious Gardens of the West Coast 7 nights 42 Themed cruises 14 12th Western Isles Panorama 7 nights 44 Highlands and islands of scotland What you need to know 112 Enriching guest speakers 15 19th St Kilda and the Outer Isles 7 nights 46 Orkney, Northern ireland, isle of Man and Norway Cabin facilities 113 26th Western Isles Wildlife 7 nights 48 Knowledgeable guides 15 Deck plans 114 SuMMER Partnerships 16 June 2nd St Kilda & Scotland’s Remote Archipelagos 7 nights 50 9th Heart of the Hebrides 7 nights 52 16th Footloose to the Outer Isles 7 nights 54 HEBRIDEAN -

THE MYTHOLOGY, TRADITIONS and HISTORY of Macdhubhsith

THE MYTHOLOGY, TRADITIONS and HISTORY OF MacDHUBHSITH ― MacDUFFIE CLAN (McAfie, McDuffie, MacFie, MacPhee, Duffy, etc.) VOLUME 2 THE LANDS OF OUR FATHERS PART 2 Earle Douglas MacPhee (1894 - 1982) M.M., M.A., M.Educ., LL.D., D.U.C., D.C.L. Emeritus Dean University of British Columbia This 2009 electronic edition Volume 2 is a scan of the 1975 Volume VII. Dr. MacPhee created Volume VII when he added supplemental data and errata to the original 1792 Volume II. This electronic edition has been amended for the errata noted by Dr. MacPhee. - i - THE LIVES OF OUR FATHERS PREFACE TO VOLUME II In Volume I the author has established the surnames of most of our Clan and has proposed the sources of the peculiar name by which our Gaelic compatriots defined us. In this examination we have examined alternate progenitors of the family. Any reader of Scottish history realizes that Highlanders like to move and like to set up small groups of people in which they can become heads of families or chieftains. This was true in Colonsay and there were almost a dozen areas in Scotland where the clansman and his children regard one of these as 'home'. The writer has tried to define the nature of these homes, and to study their growth. It will take some years to organize comparative material and we have indicated in Chapter III the areas which should require research. In Chapter IV the writer has prepared a list of possible chiefs of the clan over a thousand years. The books on our Clan give very little information on these chiefs but the writer has recorded some probable comments on his chiefship. -

Etymology of the Principal Gaelic National Names

^^t^Jf/-^ '^^ OUTLINES GAELIC ETYMOLOGY BY THE LATE ALEXANDER MACBAIN, M.A., LL.D. ENEAS MACKAY, Stirwng f ETYMOLOGY OF THK PRINCIPAL GAELIC NATIONAL NAMES PERSONAL NAMES AND SURNAMES |'( I WHICH IS ADDED A DISQUISITION ON PTOLEMY'S GEOGRAPHY OF SCOTLAND B V THE LATE ALEXANDER MACBAIN, M.A., LL.D. ENEAS MACKAY, STIRLING 1911 PRINTKD AT THE " NORTHERN OHRONIOLB " OFFICE, INYBRNESS PREFACE The following Etymology of the Principal Gaelic ISTational Names, Personal Names, and Surnames was originally, and still is, part of the Gaelic EtymologicaJ Dictionary by the late Dr MacBain. The Disquisition on Ptolemy's Geography of Scotland first appeared in the Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness, and, later, as a pamphlet. The Publisher feels sure that the issue of these Treatises in their present foim will confer a boon on those who cannot have access to them as originally published. They contain a great deal of information on subjects which have for long years interested Gaelic students and the Gaelic public, although they have not always properly understood them. Indeed, hereto- fore they have been much obscured by fanciful fallacies, which Dr MacBain's study and exposition will go a long way to dispel. ETYMOLOGY OF THE PRINCIPAI, GAELIC NATIONAL NAMES PERSONAL NAMES AND SURNAMES ; NATIONAL NAMES Albion, Great Britain in the Greek writers, Gr. "AXfSiov, AX^iotv, Ptolemy's AXovlwv, Lat. Albion (Pliny), G. Alba, g. Albainn, * Scotland, Ir., E. Ir. Alba, Alban, W. Alban : Albion- (Stokes), " " white-land ; Lat. albus, white ; Gr. dA</)os, white leprosy, white (Hes.) ; 0. H. G. albiz, swan. -

Clan Donald Lands Trust

Clan Donald Lands Trust: The First Steps A recollection from the Right Honourable Godfrey James Macdonald of Macdonald, 8th Lord Macdonald and 34th High Chief of Clan Donald, March 2019 Introduction It is now nearly fifty years since our Clan embarked on the latest chapter of our great history, namely the establishment of the Clan Donald Lands Trust. What we created then was without precedent - a Clan owning its own lands, administered by a board of Trustees from all parts of the English speaking world, for the benefit of all clansmen worldwide. This was a truly gargantuan undertaking, and as there are now only two of the original Trustees still alive, Clanranald and myself, I think that it is important to place on record those exciting, nail-biting, terrifying and sometimes desperate early days that have enabled the Clan Donald Lands Trust to become a reality. Background Following the death of my father in November 1970 and the inevitable sale of the Macdonald Estates to cover two lots of Death Duties and other inherited honourable debts some dating back to 1812, I was approached by Donald J Macdonald of Castleton, then President of the Clan Donald Society of Edinburgh. It had always been his dream that the Clan should acquire a small piece of the original Kingdom of the Isles, and that it should be held in perpetuity for all clansmen, while also concentrating on the historical and educational aspects associated with the Lordship of the Isles. The family were under enormous pressure to conclude a sale of the estate by the end of July 1971, so the Clan had less than six months to raise sufficient funds to enable it to make a meaningful offer for the estate. -

The Norse Influence on Celtic Scotland Published by James Maclehose and Sons, Glasgow

i^ttiin •••7 * tuwn 1 1 ,1 vir tiiTiv^Vv5*^M òlo^l^!^^ '^- - /f^K$ , yt A"-^^^^- /^AO. "-'no.-' iiuUcotettt>tnc -DOcholiiunc THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND PUBLISHED BY JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS, GLASGOW, inblishcre to the anibersitg. MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD., LONDON. New York, • • The Macmillan Co. Toronto, • - • The Mactnillan Co. of Canada. London, • . - Simpkin, Hamilton and Co. Cambridse, • Bowes and Bowes. Edinburgh, • • Douglas and Foults. Sydney, • • Angus and Robertson. THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND BY GEORGE HENDERSON M.A. (Edin.), B.Litt. (Jesus Coll., Oxon.), Ph.D. (Vienna) KELLY-MACCALLUM LECTURER IN CELTIC, UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW EXAMINER IN SCOTTISH GADHELIC, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON GLASGOW JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS PUBLISHERS TO THE UNIVERSITY I9IO Is buaine focal no toic an t-saoghail. A word is 7nore lasting than the world's wealth. ' ' Gadhelic Proverb. Lochlannaich is ànnuinn iad. Norsemen and heroes they. ' Book of the Dean of Lismore. Lochlannaich thi'eun Toiseach bhiir sgéil Sliochd solta ofrettmh Mhamiis. Of Norsemen bold Of doughty mould Your line of oldfrom Magnus. '' AIairi inghean Alasdair Ruaidh. PREFACE Since ever dwellers on the Continent were first able to navigate the ocean, the isles of Great Britain and Ireland must have been objects which excited their supreme interest. To this we owe in part the com- ing of our own early ancestors to these isles. But while we have histories which inform us of the several historic invasions, they all seem to me to belittle far too much the influence of the Norse Invasions in particular. This error I would fain correct, so far as regards Celtic Scotland. -

Sport & Activity Directory Uist 2019

Uist’s Sport & Activity Directory *DRAFT COPY* 2 Foreword 2 Welcome to the Sport & Activity Directory for Uist! This booklet was produced by NHS Western Isles and supported by the sports division of Comhairle nan Eilean Siar and wider organisations. The purpose of creating this directory is to enable you to find sports and activities and other useful organisations in Uist which promote sport and leisure. We intend to continue to update the directory, so please let us know of any additions, mistakes or changes. To our knowledge the details listed are correct at the time of printing. The most up to date version will be found online at: www.promotionswi.scot.nhs.uk To be added to the directory or to update any details contact: : Alison MacDonald Senior Health Promotion Officer NHS Western Isles 42 Winfield Way, Balivanich Isle of Benbecula HS7 5LH Tel No: 01870 602588 Email: [email protected] . 2 2 CONTENTS 3 Tai Chi 7 Page Uist Riding Club 7 Foreword 2 Uist Volleyball Club 8 Western Isles Sports Organisations Walk Football (40+) 8 Uist & Barra Sports Council 4 W.I. Company 1 Highland Cadets 8 Uist & Barra Sports Hub 4 Yoga for Life 8 Zumba Uibhist 8 Western Isles Island Games Association 4 Other Contacts Uist & Barra Sports Council Members Ceolas Button and Bow Club 8 Askernish Golf Course 5 Cluich @ CKC 8 Benbecula Clay Pigeon Club 5 Coisir Ghaidhlig Uibhist 8 Benbecula Golf Club 5 Sgioba Drama Uibhist 8 Benbecula Runs 5 Traditional Spinning 8 Berneray Coastal Rowing 5 Taigh Chearsabhagh Art Classes 8 Berneray Community Association -

The Arms of the Scottish Bishoprics

UC-NRLF B 2 7=13 fi57 BERKELEY LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORN'A \o Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2008 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/armsofscottishbiOOIyonrich /be R K E L E Y LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORN'A h THE ARMS OF THE SCOTTISH BISHOPRICS. THE ARMS OF THE SCOTTISH BISHOPRICS BY Rev. W. T. LYON. M.A.. F.S.A. (Scot] WITH A FOREWORD BY The Most Revd. W. J. F. ROBBERDS, D.D.. Bishop of Brechin, and Primus of the Episcopal Church in Scotland. ILLUSTRATED BY A. C. CROLL MURRAY. Selkirk : The Scottish Chronicle" Offices. 1917. Co — V. PREFACE. The following chapters appeared in the pages of " The Scottish Chronicle " in 1915 and 1916, and it is owing to the courtesy of the Proprietor and Editor that they are now republished in book form. Their original publication in the pages of a Church newspaper will explain something of the lines on which the book is fashioned. The articles were written to explain and to describe the origin and de\elopment of the Armorial Bearings of the ancient Dioceses of Scotland. These Coats of arms are, and have been more or less con- tinuously, used by the Scottish Episcopal Church since they came into use in the middle of the 17th century, though whether the disestablished Church has a right to their use or not is a vexed question. Fox-Davies holds that the Church of Ireland and the Episcopal Chuich in Scotland lost their diocesan Coats of Arms on disestablishment, and that the Welsh Church will suffer the same loss when the Disestablishment Act comes into operation ( Public Arms). -

Ross of Mull & Iona Community Plan

Ross of Mull & Iona Community Plan 2011 In 2010 the Ross of Mull (including Pennyghael and Tiroran) and Iona were identified by Highlands and Islands Enterprise as being an area which could receive support through their Growth at the Edge (GatE) programme. This involved supporting an anchor organisation, in this case Mull and Iona Community Trust, to facilitate community growth through the employment of a Local Development Officer and the creation of a Community Plan based on consultation with the local community and a socio-economic analysis. The project is funded by Highlands and Islands Enterprise & LEADER. The document will always be open to suggestions and changes from the community and should not be regarded as being inflexible. Pennyghael village, A. MacCallum 2 Contents Introduction 4 How the plan was created 5 Our vision 6 Our Outcomes 6 Section 1 Population 7 Section 2 Physical Infrastructure 8 Section 3 Business, Employment & Economy 11 Section 4 Culture and Heritage 14 Section 5 Community Facilities & Social Infrastructure 16 How does the plan fit with European, national and local priorities 18 Timeline 20 Kilvickeon Beach 3 Introduction “It is a beautiful place to be brought up and you get to know everyone really well.” Oban High School Pupil About the plan In creating this plan, we aim to define our scope of activities over the next 5-10 years and give you an insight into how wide our ambitions are to be a sustainable community and where we, as a community, intend to go. The plan is an opportunity for our communities to control our development and implement projects, which will be of direct benefit to the Ross of Mull and Iona. -

The Clan Macneil

THE CLAN MACNEIL CLANN NIALL OF SCOTLAND By THE MACNEIL OF BARRA Chief of the Clan Fellow of the Society of .Antiquarie1 of Scotland With an Introduction by THE DUKE OF ARGYLL Chief of Clan Campbell New York THE CALEDONIAN PUBLISHING COMPANY MCMXXIII Copyright, 1923, by THE CALEDONIAN PUBLISHING COMPANY Entered at Stationers~ Hall, London, England .All rights reser:ved Printed by The Chauncey Holt Compan}'. New York, U. 5. A. From Painting by Dr. E, F. Coriu, Paris K.1s11\1 UL CASTLE} IsLE OF BAH HA PREFACE AVING a Highlander's pride of race, it was perhaps natural that I should have been deeply H interested, as a lad, in the stirring tales and quaint legends of our ancient Clan. With maturity came the desire for dependable records of its history, and I was disappointed at finding only incomplete accounts, here and there in published works, which were at the same time often contradictory. My succession to the Chiefship, besides bringing greetings from clansmen in many lands, also brought forth their expressions of the opinion that a complete history would be most desirable, coupled with the sug gestion that, as I had considerable data on hand, I com pile it. I felt some diffidence in undertaking to write about my own family, but, believing that under these conditions it would serve a worthy purpose, I commenced this work which was interrupted by the chaos of the Great War and by my own military service. In all cases where the original sources of information exist I have consulted them, so that I believe the book is quite accurate. -

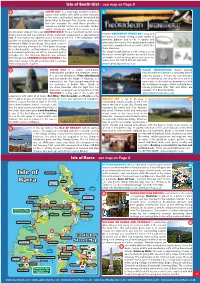

Isle of Barra - See Map on Page 8

Isle of South Uist - see map on Page 8 65 SOUTH UIST is a stunningly beautiful island of 68 crystal clear waters with white powder beaches to the west, and heather uplands dominated by Beinn Mhor to the east. The 20 miles of machair that runs alongside the sand dunes provides a marvellous habitat for the rare corncrake. Golden eagles, red grouse and red deer can be seen on the mountain slopes to the east. LOCHBOISDALE, once a major herring port, is the main settlement and ferry terminal on the island with a population of approximately Visit the HEBRIDEAN JEWELLERY shop and 300. A new marina has opened, and is located at the end of the breakwater with workshop at Iochdar, selling a wide variety of facilities for visiting yachts. Also newly opened Visitor jewellery, giftware and books of quality and Information Offi ce in the village. The island is one of good value for money. This quality hand crafted the last surviving strongholds of the Gaelic language jewellery is manufactured on South Uist in the in Scotland and the crofting industries of peat cutting Outer Hebrides. and seaweed gathering are still an important part of The shop in South Uist has a coffee shop close by everyday life. The Kildonan Museum has artefacts the beach, where light snacks are served. If you from this period. ASKERNISH GOLF COURSE is the are unable to visit our shop, please visit us on our oldest golf course in the Western Isles and is a unique online store. Tel: 01870 610288. HS8 5QX. -

Is There Any Correlation Between the Etymology of Manx Family Names and Their Male Line Genetic Origins? Introduction Background

Is there any correlation between the etymology of Manx family names and their male line genetic origins? Introduction When the Manx Y-DNA study1 was initiated in 2010 three main objectives were set:- • Use Y-DNA testing to identify the earlier genetic origins of the ca 135 indigenous Manx male line families and any genetic connections between them. • To identify the timescales in which the early populations of the Isle of Man arrived on the Island. • To see if there is any connection between the etymology2 of the surviving indigenous Manx family names and their male line genetic origins. The first two of these objectives have been largely met3 and the analysis contained within this paper now addresses the third and final objective by attempting to establish whether there is any visible correlation between the perceived (documented) origin of a Manx family name and the real genetic origins of the male family line bearing that name as identified within the Manx Y-DNA Study. Background Those people who claim Manx ancestry take great pride in their history and origins. The closeness of a stable population living on a small Island together has meant over the centuries that different families have mingled closely with each other and hence possess a consciousness and knowledge of the history of their own particular family on the Island, to a degree not usually seen, for example, in larger and wider communities as in England and elsewhere. The succession of incoming settlers and invaders over the centuries to the Isle of Man has left an indelible legacy on the Island in terms of the inherited customs, place and family names, genetics and physical traces etc.