Let's Pretend

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lev Vygotsky Area of Research

Lev Vygotsky Area of Research ● Vygotsky's first big research project was in 1925 ● Vygotsky's theories stress the fundamental role of social interaction in the development of cognition Vygotsky, 1978, as he believed strongly that community plays a central role in the process of "making meaning." ● Unlike Piaget's notion that children’s development must necessarily precede their learning, Vygotsky argued, "learning is a necessary and universal aspect of the process of developing culturally organized.” Process of Research ● Started teaching at various institutions ● First big research project was in 1925 with his Psychology of Art ● Pursued a career as a psychologist working with Alexander Luria and Alexei Leontiev ● Began the Vygotskian approach to psychology with Alexander Luria and Alexei Leontiev ● His works were revealed after the Cold War ended ● Wrote several articles and books on the subject of his theories and psychology -Thought and Language(1934) ● His research in how children solve their problems that surpassed their level of development led Vygotsky to create the Zone of Proximal Development theory Age of Children Researched ● Crisis of the newborn. ● Infancy (two months to one year). ● Crisis at age one. ● Early childhood (one to three years). ● Crisis at age three. ● Preschool age (three to seven years). ● Crisis at age seven. ● School age (eight to twelve years). ● Crisis at age thirteen. ● Age of puberty (fourteen to eighteen years). ● Crisis at age seventeen. Research Findings ● Private speech: Where children speak themselves to plan or guide their own behavior this is most common among pre schoolers. ● Sociocultural (ZPD) Zone of proximal development Vygotsky believed For example a child accomplishes a task he/she cannot do alone by a more skilled person. -

How Much of a Loss Is the Loss of Self? Undersanding

This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution and sharing with colleagues. Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party websites are prohibited. In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or institutional repository. Authors requiring further information regarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies are encouraged to visit: http://www.elsevier.com/copyright Author's personal copy New Ideas in Psychology 29 (2011) 98–105 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect New Ideas in Psychology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/newideapsych How much of a loss is the loss of self? Understanding Vygotsky from a social therapeutic perspective and vice versaq Lois Holzman* East Side Institute for Group and Short Term Psychotherapy, 920 Broadway, New York NY 10010, United States abstract Keywords: Using the example of Fred Newman’s social therapy, a methodology that works with the Marx human capability of growing as social units, the contemporary self is explored as an Vygotsky impediment to human development and learning. Following Karl Marx in political Wittgenstein philosophy and Lev Vygotsky in child psychology, it is the group/the collective/the mass Self that engages in developmental activity. In losing the self, we gain the opportunity to create Psychotherapy Social therapy collectivity and in that process come to sense the social-relational-collective quality of creativity and development. -

The Transition from Studying Philosophy to Doing Philosophy

Teaching Philosophy 34:3, September 2011 241 The Transition from Studying Philosophy to Doing Philosophy JOHN RUDISILL The College of Wooster Abstract: In this paper I articulate a minimal conception of the idea of doing philosophy that informs a curriculum and pedagogy for producing students who are capable of engaging in philosophical activity and not just competent with a specific domain of knowledge. The paper then relates, by way of back- ground, the departmental assessment practices that have played a vital role in the development of my department’s current curriculum and in particular in the design of a junior-year seminar in philosophical research required of all majors. After a brief survey of the learning theory literature that has informed its design, I share the content of this junior-year seminar. In the paper’s conclusion I provide some initial data that indicates our approach to curriculum and pedagogy has had a positive impact on student achievement with respect to reaching the learning goals associated with “doing” as opposed to “merely studying” philosophy. 1. Introduction Capstone projects are common among liberal arts colleges and fre- quently carry an expectation that the final product demonstrates the student’s achievement of becoming a budding biologist, historian, sociologist, philosopher and so on. Even without a formal capstone requirement, I would hope that my philosophy students could—as they finish their undergraduate studies—demonstrate such an achievement. This is because the full set of benefits made available by an education in philosophy includes but extends well beyond knowledge of the history of philosophy and mastery of a philosophical lexicon. -

The Points of Viewing Theory for Engaged Learning with Digital Media

The Points of Viewing Theory for Engaged Learning with Digital Media Ricki Goldman New York University John Black Columbia University John W. Maxwell Simon Fraser University Jan J. L. Plass New York University Mark J. Keitges University of Illinois, Urbana Champaign - 1 - Introduction Theories are dangerous things. All the same we must risk making one this afternoon since we are going to discuss modern tendencies. Directly we speak of tendencies or movements we commit to, the belief that there is some force, influence, outer pressure that is strong enough to stamp itself upon a whole group of different writers so that all their writing has a certain common likeness. — Virginia Woolff, The Leaning Tower, lecture delivered to the Workers' Educational Association, Brighton (May 1940). With full acknowledgement of the warning from the 1940 lecture by Virginia Woolf, this chapter begins by presenting a theory of mind, knowing only too well, that “a whole group of different” learning theorists cannot find adequate coverage under one umbrella. Nor should they. However, there is a movement occurring, a form of social activism created by the affordances of social media, an infrastructure that was built incrementally during two to three decades of hard scholarly research that brought us to this historic time and place. To honor the convergence of theories and technologies, this paper proposes the Points of Viewing Theory to provide researchers, teachers, and the public with an opportunity to discuss and perhaps change the epistemology of education from its formal structures to more do-it-yourself learning environments that dig deeper and better into content knowledge. -

Developmental Psychology: Incorporating Piaget's and Vygotsky's Theories in Classrooms

Journal of Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives in Education Vol. 1, No. 1 (May 2008) 59 - 67 Developmental Psychology: Incorporating Piaget’s and Vygotsky’s Theories in Classrooms Barbara Blake and Tambra Pope In today’s society, there is disagreement of their students’ cognitive development, which will among researchers and educators as to the role of lead to the needs of the whole child being satisfied. developmental psychology and its application in the Cognitive psychology is a branch of psychology elementary classrooms. It is widely accepted in the that focuses on studies mental processes, which educational field that children must go through the include how people think, perceive, remember, and process of learning to think and thinking to learn. learn. Its core focus is on how people acquire, Therefore, teachers, who can incorporate the process, and store information. It is advantageous theories of Piaget and Vygotsky into their teaching for teachers to understand cognitive psychology strategies, will be better able to increase student because it can help them improve their teaching and achievement. student learning. Teachers become more cognizant Developmental Psychology, the study of to how people process, learn, and remember age-related changes in behavior, examines the information, which helps them plan more effective psychological processes of development, which lessons and create positive learning environments means it describes the sequence of biological, for their students. By using appropriate cognitive, and socio-emotional changes that humans developmental instructional techniques, teachers undergo as they grow older. It describes the growth have been able to increase the test scores of children of humans, which consists of physical, emotional, in public schools (Black & Green, 2005). -

The Historic Importance of LS Vygotsky's “The Psychology of Art

International Journal of Psychological Research ISSN: 2011-2084 [email protected] Universidad de San Buenaventura Colombia Khinkanina, Alla The Historic Importance of L. S. Vygotsky’s “The Psychology of Art” and Some Problems of Modern Psychological and Pedagogical Field International Journal of Psychological Research, vol. 7, núm. 2, 2014, pp. 85-91 Universidad de San Buenaventura Medellín, Colombia Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=299032684009 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative INT.J.PSYCHOL.RES. 2014; 7 (2): 85-91 The Historic Importance of L. S. Vygotsky’s “The Psychology of Art” and Some Problems of Modern Psychological and Pedagogical Field La importancia histórica de L. S. Vygotsky: “La Psicología del arte” y algunos problemas de la Psicología y Pedagogía Moderna. R e f l e c t i o n a Alla Khinkanina * a Department of Psychology, Volga State University of Technology, Yoshkar-Ola, Russia. Article History ARTICLE INFO Received: 20-05-2014 Revised: 10-08-2014 Accepted: 04-09-2014 ABSTRACT Key words: The article deals with the importance of L. S. Vygotsky‟s paper “The Psychology Cultural-historical of Art” in the present time. The shortage of ideal values is the reality of this time that in a psychology, game, certain way arises the issues of children and young people‟s cultural evolution. Cultural psychological- and historic theory of L. -

Lev Vygotsky's Cultural-Historical Theory of Development and T

Articles Papeles del Psicólogo / Psychologist Papers , 2018. Vol. 39(2), pp. 150-154 https://doi.org/10.23923/pap.psicol2018.2862 http://www.papelesdelpsicologo.es http:// www.psychologistpapers.com LEV VYGOTSKY’S CULTURAL-HISTORICAL THEORY OF DEVELOPMENT AND THE PROBLEM OF MENTAL TOOLS Nikolay Veraksa 1 and Aleksander Veraksa 2 1Russian Academy of Education (Moscow, Russia). 2Faculty of Psychology, Lomonosov Moscow State University (Moscow, Russia) El artículo pretende describir los enfoques para comprender las formas de mediación utilizadas en programas educacionales para niños preescolares, como una de las principales líneas de aplicación psicológica en Rusia. En gran medida, se basan en el enfoque cultural-histórico, desarrollado por Lev Vygotskyt y sus seguidores. Se muestra cómo se desarrolló y se aplica actualmente la idea de utilizar herramientas mentales en la educación preescolar. De acuerdo con la teoría cultural-histórica, el ejemplo es una de las herramientas culturales, cuyo dominio por el niño tiene lugar en la zona de desarrollo próximo. Otra herramienta cultural es el signo, y especialmente la palabra. Los seguidores de Vigotsky elaboraron tales herramientas como modelos visuales, esquemas, y símbolos. La aplicación de los programas educacionales de herramientas mentales se analizaron en diferentes esferas (desarrollo del lenguaje, desarrollo cognitivo, y desarrollo volitivo), como ejemplos de los programas educacionales más extendidos en Rusia. Palabras clave: Herramientas mentales, Herramientas culturales, Zona de desarrollo próximo, Mediación, Iniciativa infantil. The article is aimed at describing approaches towards understanding of mediation forms used in educational programs for preschool children as one of the major lines of psychology implementation in Russia. To a large extent, they are based on the cultural-historical approach, developed by Lev Vygotsky and his followers. -

Undecidable Emotions (What Is Social Therapy? and How Is It Revolutionary?)

Undecidable Emotions (What is Social Therapy? And How is it Revolutionary?) Fred Newman Mathematical Meanderings Social therapy, as I understand it, is done (performed) with groups of people (2). Hence, a most basic (theoretic) question, so far as I can tell, is: what is a group? My answer(s) to this question (fundamental to my understanding of psychology and therapy) derive more from my studies of set theory and foundations of logic and mathematics (which I have studied modestly) than from anthropology or sociology (which I have not studied seriously at all). What is a group? Is a group totally definable in terms of the elements which make it up or does the group have an independent existence in itself? Philosophers (including philosophically inclined logicians and mathematicians) have been asking such questions for centuries. No less a 20th century giant than Kurt Gôdel insisted that his monumental proof of undecidability rested on his Platonistic (philosophically realistic) view of mathematical logical concepts (including, most fundamentally, groups or sets) (3). The view that groups were nothing more than "the sum of their parts" -- nominalism -- dominated early twentieth century positivistic thinking. Ironically, Gôdel's 1930s proof, while a conceptual philosophical rejection of positivism, led to mathematical-logical discoveries which in turn formulated technological discoveries in cybernetics and computer theory and practice which, to some extent, advanced the general modernist belief in a kind of soft positivism. Only in the last twenty or thirty years of the 20th century did postmodernism (typically unselfconsciously) begin to take seriously the foundational implications of Gôdel's discovery. -

Lev Vygotsky: Philologist and Defectologist, a Sociointellectual Biography1

Lev Vygotsky: Philologist and Defectologist, A Sociointellectual Biography1 ANTON YASNITSKY York University Among the pioneers of psychology, Lev Vygotsky (1896-1934) may be the best known of those who are least understood. This is not just a problem of historical scholarship: The misunderstanding of Vygotsky started with his own students and collaborators—during his lifetime—and continued after his death. It is, in other words, integrated into the litera ture. And that literature, as a result, appears fractured and inconsistent. Indeed, the larg est and the best intellectual biography of Vygotsky is titled Understanding Vygotsky: A Quest for Synthesis (van der Veer & Valsiner, 1991). Yet even this excellent book is far from providing a full and complete story. The dis covery of the real Vygotsky is still to come. Figure 7.1 Lev Vygotsky, 1925. There are many reasons for systematic misunderstanding—even misrepresenta tion. Among them we can include Vygotsky's changes in theoretical outlook; his premature death at the age of 37, when he was in the middle of the most prolific period of his career; the lack of public access to manuscripts and documents in the Vygotsky archives; problems of posthumous editing; and the censorship of his works published in the Soviet Union, the effects of which were in turn multiplied 109 rui i wn YAsni i br\Y LEV VYGOTSKY 111 by mistakes that accumulated in Western translations (Yasnitsky, 2010; van der conferences" to coordinate their research. This network was instrumental in the Veer & Yasnitsky, in press). These confusions, and many others, have resulted in an development and dissemination of Vygotskian thought during his lifetime, although image of Vygotsky that can be described charitably as having been constructed by especially after his death, both in the Soviet Union and internationally. -

LOIS HOLZMAN East Side Institute for Group and Short Term

LOIS HOLZMAN East Side Institute for Group and Short Term Psychotherapy 920 Broadway, 14th floor, New York NY 10010 212.941.8906 (phone) 212.941.0511 (fax) [email protected] www.loisholzman.net and www.eastsideinstitute.org EDUCATION Ph.D. in Developmental Psychology Columbia University, 1977 Graduate Study in Linguistics Columbia University and Brown University, 1968-1970 Bachelor of Arts, English Rhode Island College, 1967 RESEARCH AND TEACHING EXPERIENCE Director, 2001-present East Side Institute for Group and Short Term Psychotherapy, New York NY (Director of Research & Educational Programs, 1989-2001) Initiated Research Projects & Gatherings • 2008, International Conference—Performing the World 2008 • 2007, International Conference—Performing the World 4: The Performance of Community and the Community of Performance • 2005, International Conference—Performing the World 3: The Performance of Creativity and the Creativity of Performance • 2005, Conference: Vygotsky at Work and Play in Educational, Therapeutic and Organizational Setttings • 2003, International Conference—Performing the World 2: The Second International Conference Exploring the Potential of Performance for Personal, Organizational and Social-Cultural Change. • 2002, Young People Learn by Studying Themselves: The All Stars Talent Show in Action (Youth participatory study of youth development-supplemental education program). Funded by The Virginia Wellington Cabot Foundation. • 2002, Weekend Retreat for Medical Professionals: A Dialogue on Changing the Culture of Healthcare. • 2001, International Conference—Performing the World: Communication, Improvisation and Societal Practice • 2001, Weekend Retreat for Sex Education/Teen Pregnancy Prevention Professionals. Funded by Cabot Family Charitable Trust. • 2000, Growing Up Performed (Performance-based outside-of-school program to promote the social and emotional development of young people who have experienced abuse in their lives). -

When Confucianism Meets Vygotskian Practices : an Ethnography of Teaching and Learning EFL in a Korean University

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2004 Globalization of English teaching practices : when Confucianism meets Vygotskian practices : an ethnography of teaching and learning EFL in a Korean university. Sun Joo Huh University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Huh, Sun Joo, "Globalization of English teaching practices : when Confucianism meets Vygotskian practices : an ethnography of teaching and learning EFL in a Korean university." (2004). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 5686. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/5686 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GLOBALIZATION OF ENGLISH TEACHING PRACTICES: WHEN CONFUCIANISM MEETS VYGOTSKIAN PRACTICES - AN ETHNOGRAPHY OF TEACHING AND LEARNING EFL IN A KOREAN UNIVERSITY A Dissertation Presented by SUN JOO HUH Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION May 2004 School of Education © Copyright by Sun Joo Huh 2004 All Rights Reserved GLOBALIZATION OF ENGLISH TEACHING PRACTICES: WHEN CONFUCIANISM MEETS VYGOTSKIAN PRACTTICES-AN ETHNOGRAPHY OF TEACHING AND LEARNING EFL IN A KOREAN UNIVERISTY A Dissertation Presented by SUN JOO HUH Approved as to style and content by: Theresa Austin, Chair ja—~£= Margaret Gebhatfi Member Jo^rater, Member DEDICATION I dedicate this dissertation to my beloved son, Vincent Doe Hyun Kim, hoping that someday he would understand the complexities of life and inevitable sacrifices we are forced to make. -

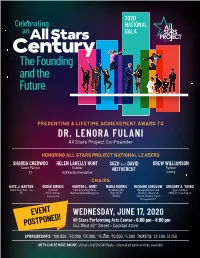

Century the Founding and the Future

2020 Celebrating NATIONAL an GALA All Stars Century The Founding and the Future PRESENTING A LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARD TO DR. LENORA FULANI All Stars Project Co-Founder HONORING ALL STARS PROJECT NATIONAL LEADERS SHARDA CHERWOO HELEN LAKELLY HUNT SUZU and DAVID DREW WILLIAMSON Senior Partner Founder NEITHERCUT Partner EY HLH Family Foundation Cooley CHAIRS KATE J. BARTON DEREK DIRISIO HUNTER L. HUNT MARIA MORRIS RICHARD SOKOLOW GREGORY A. TOSKO Global Vice Chair - Tax President Chief Executive Officer Board Director Managing Director and Vice Chairman EY PSEG Services Hunt Consolidated Energy, LLC Retired EVP Director of Research CBRE Tri-State Region Corporation MetLife Davidson Kempner Capital Management, LP EVENT WEDNESDAY, JUNE 17, 2020 All Stars Performing Arts Center • 6:00 pm - 8:00 pm POSTPONED! 543 West 42nd Street • Cocktail Attire SPONSORSHIPS: $100,000, $50,000, $25,000, $15,000, $10,000, $5,000 TICKETS: $2,500, $1,250 GIFTS CAN BE MADE ONLINE: allstars.org/2020ASPgala • Journal ad sponsorships available Celebrating anAll Stars Century The Founding 2020 NATIONAL and the Future GALA A message from our CEO GABRIELLE L. KURLANDER CELEBRATING AN ALL STARS CENTURY THE FOUNDING AND THE FUTURE “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world: indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.” – Margaret Mead The All Stars Project has always been visionary about creating community and connecting young people who are growing up poor to the mainstream of American life. As we look ahead, I am proud to say that 50 years of painstaking and intentional organizing has brought forth a powerful new movement for human development, focused on youth and committed to engaging poverty across our country in dynamic new ways.