WHERE the PANDEMIC HAS LED US Teesta Setalvad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sovereignty and Social Change in the Wake of India's Recent Sodomy Cases

Alabama Law Scholarly Commons Articles Faculty Scholarship 2017 Sovereignty and Social Change in the Wake of India's Recent Sodomy Cases Deepa Das Acevedo University of Alabama - School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.ua.edu/fac_articles Recommended Citation Deepa Das Acevedo, Sovereignty and Social Change in the Wake of India's Recent Sodomy Cases, 40 B. C. Int'l & Comp. L. Rev. 1 (2017). Available at: https://scholarship.law.ua.edu/fac_articles/450 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Alabama Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of Alabama Law Scholarly Commons. SOVEREIGNTY AND SOCIAL CHANGE IN THE WAKE OF INDIA'S RECENT SODOMY CASES DEEPA DAS ACEVEDO* Abstract: American constitutional law scholars have long questioned whether courts can truly drive social reform, and this uncertainty remains even in the wake of recent landmark decisions affecting the LGBT community. In contrast, court watchers in India-spurred by developments in a special type of legal ac- tion developed in the late 1970s known as public interest litigation (PIL)-have only recently begun to question the judiciary's ability to promote progressive social change. Indian scholarship on this point has veered between despair that PIL cases no longer reliably produce good outcomes for India's most disadvan- taged and optimism that public interest litigation can be returned to its glory days of heroic judicial intervention. Perhaps no pair of cases so nicely captures this dichotomy as the 2009 decision in Naz Foundation v. -

An Interview with Teesta Setalvad

Jindal Global Law Review https://doi.org/10.1007/s41020-020-00116-3 ARTICLE Proto‑fascism and State impunity in Majoritarian India: An Interview with Teesta Setalvad Oishik Sircar1 © O.P. Jindal Global University (JGU) 2020 Abstract This interview with Teesta Setalvad was conducted in the wake of the February 2020 anti-Muslim violence in North East Delhi. Drawing on her vast experience as a human rights activist, journalist, and peace educator, Setalvad’s responses map the continuum — across years, anti-minority pogroms and ruling parties with divergent ideologies — of the cultures of hate, and the practices of state repression and impu- nity in a proto-fascist India. Setalvad ofers an interrogation of the ideology of the Hindu right, delves into the historical trajectories of the rise of the Rashtriya Sway- amsevak Sangh (RSS) and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). She also charts the repeating patterns of police and media complicity in fomenting anti-minority hate and critically analyses the contradictory role of the criminal law and the Constitu- tion of India in both enabling and resisting communal violence. In conclusion, she ofers hopeful strategies for keeping alive the promise of secularism. Keywords State impunity · Hindutva · Gujarat 2002 · Pogrom · Genocide 1 Introduction The cover of Teesta Setalvad’s memoir — Foot Soldier of the Constitution — features a photograph of her looking directly into the eyes of the reader.1 Her face is partly lit and lightly silhouetted, her eyes simultaneously conveying an invitation and a provocation. One might use words like determination, courage and fortitude to describe the expres- sion on her face — as the blurb on the back cover of the book does. -

Public Interest Litigation and Political Society in Post-Emergency India

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Columbia University Academic Commons Competing Populisms: Public Interest Litigation and Political Society in Post-Emergency India Anuj Bhuwania Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2013 © 2013 Anuj Bhuwania All rights reserved ABSTRACT Competing Populisms: Public Interest Litigation and Political Society in Post-Emergency India Anuj Bhuwania This dissertation studies the politics of ‘Public Interest Litigation’ (PIL) in contemporary India. PIL is a unique jurisdiction initiated by the Indian Supreme Court in the aftermath of the Emergency of 1975-1977. Why did the Court’s response to the crisis of the Emergency period have to take the form of PIL? I locate the history of PIL in India’s postcolonial predicament, arguing that a Constitutional framework that mandated a statist agenda of social transformation provided the conditions of possibility for PIL to emerge. The post-Emergency era was the heyday of a new form of everyday politics that Partha Chatterjee has called ‘political society’. I argue that PIL in its initial phase emerged as its judicial counterpart, and was even characterized as ‘judicial populism’. However, PIL in its 21 st century avatar has emerged as a bulwark against the operations of political society, often used as a powerful weapon against the same subaltern classes whose interests were so loudly championed by the initial cases of PIL. In the last decade, for instance, PIL has enabled the Indian appellate courts to function as a slum demolition machine, and a most effective one at that – even more successful than the Emergency regime. -

Compounding Injustice: India

INDIA 350 Fifth Ave 34 th Floor New York, N.Y. 10118-3299 http://www.hrw.org (212) 290-4700 Vol. 15, No. 3 (C) – July 2003 Afsara, a Muslim woman in her forties, clutches a photo of family members killed in the February-March 2002 communal violence in Gujarat. Five of her close family members were murdered, including her daughter. Afsara’s two remaining children survived but suffered serious burn injuries. Afsara filed a complaint with the police but believes that the police released those that she identified, along with many others. Like thousands of others in Gujarat she has little faith in getting justice and has few resources with which to rebuild her life. ©2003 Smita Narula/Human Rights Watch COMPOUNDING INJUSTICE: THE GOVERNMENT’S FAILURE TO REDRESS MASSACRES IN GUJARAT 1630 Connecticut Ave, N.W., Suite 500 2nd Floor, 2-12 Pentonville Road 15 Rue Van Campenhout Washington, DC 20009 London N1 9HF, UK 1000 Brussels, Belgium TEL (202) 612-4321 TEL: (44 20) 7713 1995 TEL (32 2) 732-2009 FAX (202) 612-4333 FAX: (44 20) 7713 1800 FAX (32 2) 732-0471 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] July 2003 Vol. 15, No. 3 (C) COMPOUNDING INJUSTICE: The Government's Failure to Redress Massacres in Gujarat Table of Contents I. Summary............................................................................................................................................................. 4 Impunity for Attacks Against Muslims............................................................................................................... -

2018, Four Senior Most Judges of the Supreme Court, Namely Justice

Rebellion in the Supreme Court By N.T.Ravindranath, dated 12-03-2018 On January 12th, 2018, four senior most judges of the Supreme Court, namely justice Chelameshwar, Ranjan Gogoi, Joseph Kurian and Madan Lokur stunned the people of India by openly revolting against the Chief Justice of India and conducting a press conference in Delhi accusing CJI Deepak Mishra of selective allocation of important cases for hearing to junior judges in an improper and inappropriate manner. Allocation of cases to different benches is the sole prerogative of the Chief Justice of India. Many important cases have been allocated to junior judges in the past and there is nothing unusual or unfair about it. The four dissident judges claim that all judges are equals and that the chief justice is only the first among the equals. On the other hand, contradicting their own assertion, they refuse to treat their own junior judges as their equals. Thus, their allegations against the chief justice Deepak Mishra can be seen as baseless and without any merit. Hence, the open mutiny staged by the four rebel judges is highly condemnable. This episode has not cast any shadow of doubt on the reputation and credibility of CJI Deepak Mishra. On the contrary, it is the four rebel judges who now stand exposed as crooks by their open expression of frustration and anger over non-allocation of certain cases of their interest to them. Their open revolt has only helped to expose their undue interest in getting certain cases allocated to them for their own vested interests which has raised questions about the impartiality and credibility of the Supreme Court. -

Breathing Life Into the Constitution

Breathing Life into the Constitution Human Rights Lawyering In India Arvind Narrain | Saumya Uma Alternative Law Forum Bengaluru Breathing Life into the Constitution Human Rights Lawyering In India Arvind Narrain | Saumya Uma Alternative Law Forum Bengaluru Breathing Life into the Constitution Human Rights Lawyering in India Arvind Narrain | Saumya Uma Edition: January 2017 Published by: Alternative Law Forum 122/4 Infantry Road, Bengaluru - 560001. Karnataka, India. Design by: Vinay C About the Authors: Arvind Narrain is a founding member of the Alternative Law Forum in Bangalore, a collective of lawyers who work on a critical practise of law. He has worked on human rights issues including mass crimes, communal conflict, LGBT rights and human rights history. Saumya Uma has 22 years’ experience as a lawyer, law researcher, writer, campaigner, trainer and activist on gender, law and human rights. Cover page images copied from multiple news articles. All copyrights acknowledged. Any part of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted as necessary. The authors only assert the right to be identified wtih the reproduced version. “I am not a religious person but the only sin I believe in is the sin of cynicism.” Parvez Imroz, Jammu and Kashmir Civil Society Coalition (JKCSS), on being told that nothing would change with respect to the human rights situation in Kashmir Dedication This book is dedicated to remembering the courageous work of human rights lawyers, Jalil Andrabi (1954-1996), Shahid Azmi (1977-2010), K. Balagopal (1952-2009), K.G. Kannabiran (1929-2010), Gobinda Mukhoty (1927-1995), T. Purushotham – (killed in 2000), Japa Lakshma Reddy (killed in 1992), P.A. -

Open Letter Against Sec 377 by Amartya Sen, Vikram Seth and Others, 2006

Open Letters Against Sec 377 These two open letters bring together the voices of many of the most eminent and respected Indians, collectively saying that on the grounds of fundamental human rights Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, a British-era law that criminalizes same-sex love between adults, should be struck down immediately. The eminent signatories to these letters are asking our government, our courts, and the people of this country to join their voices against this archaic and oppressive law, and to put India in line with other progressive countries that are striving to realize the foundational goal of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights that “All persons are born free and equal in dignity and rights.” They have come together to defend the rights and freedom not just of sexual minorities in India but to uphold the dignity and vigour of Indian democracy itself. Navigating Through This Press Kit This kit contains, in order, i. A statement by Amartya Sen, Nobel Laureate ii. The text of the main Open Letter iii. The list of Signatories iv. Sexual minorities in India - Frequently Asked Questions and Clarifications v. A summary of laws concerning the rights and situation of sexual minorities globally vi. Contact Information for further information/interviews Strictly embargoed until 16th September 2006 Not for distribution or publication without prior permission of the main signatories. All legal rights reserved worldwide. 1 In Support Cambridge 20 August 2006 A Statement in Support of the Open Letter by Vikram Seth and Others I have read with much interest and agreement the open letter of Vikram Seth and others on the need to overturn section 377 of the Indian Penal Code. -

India: Provide Full Protection to Human Rights Defender Teesta Setalvad

India: Provide full protection to human rights defender Teesta Setalvad (Bangkok, 24 July 2015) - The Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (FORUM-ASIA) strongly urges the Government of India and the Indian judiciary to drop all charges against the social activist Teesta Setalvad and to provide her the full protection she has a right to under national and international law. Teesta, who is accused of violating the Foreign Contribution Regulation Act (FCRA), is a well-known human rights defender who has worked tirelessly seeking justice for the victims of the 2002 Gulbarg Society Massacre in Gujarat. FORUM-ASIA strongly condemns the earlier decision today by the Mumbai Special Court not to grant Teesta anticipatory bail, and applauds that she was still granted bail later today by the Bombay High Court. “The Indian judiciary’s failure to reject the spurious charges against Teesta, demonstrates a worrying trend of the criminalisation of human rights defenders, which stifles their dissent,” comments Evelyn Balais- Serrano, Executive Director of FORUM-ASIA, “The rights of all human rights defenders should be protected at all times, and the judiciary must take measures to ensure that this is fulfilled.” On 8 July 2015, the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) filed a case against both Teesta and the NGO Citizens for Justice and Peace under sections 35, 37 of the Penal Code and sections 3, 11 and 19 of the Foreign Contribution Regulation Act (FCRA) based on alleged violations of the FCRA. Despite Teesta’s cooperation with the investigation, the CBI raided the office of Citizens for Justice and Peace and the residence of Teesta and Javed on 14 July 2015. -

Table of Contents

iv Table of Contents Foreword ........................................................................................................ i Mani Shekhar Singh Editorial ......................................................................................................... ii Dikshit Bhagabati, Malini Chidambaram, Neeta Stephen A Lexicon of Law and Listening ..................................................................... 2 James Parker The Dreaming, Never to be Lost .................................................................. 24 Upendra Baxi Indian Necropolitics and Weaponizing Covid-19 in Kashmir ...................... 78 Ather Zia Hopeful Rantings of a Dalit-Queer Person ................................................... 91 Dhiren Borisa Queerings .................................................................................................... 97 Oishik Sircar Writing Against the Violence of History ..................................................... 103 Shals Mahajan The Ineffable Somethingness of Love and Revolution ................................. 108 Rahul Rao “But No One Gets Used to Living Here” ..................................................... 113 Jordy Rosenberg The Ministry for the Unconsoled ................................................................ 123 Arundhati Roy Seasons of Life and Seasons of Law .............................................................. 129 Dolly Kikon Pandemic Diary in Three Parts.................................................................... 140 Vasuki Nesiah Where -

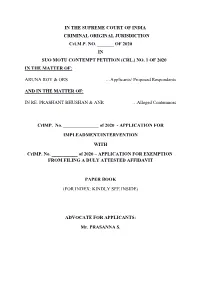

Of 2020 in Suo Motu Contempt Petition (Crl.) No

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CRIMINAL ORIGINAL JURISDICTION Crl.M.P. NO. _______ OF 2020 IN SUO MOTU CONTEMPT PETITION (CRL.) NO. 1 OF 2020 IN THE MATTER OF: ARUNA ROY & ORS …Applicants/ Proposed Respondents AND IN THE MATTER OF: IN RE. PRASHANT BHUSHAN & ANR …Alleged Contemnors CrlMP. No. _______________ of 2020 - APPLICATION FOR IMPLEADMENT/INTERVENTION WITH CrlMP. No. ___________ of 2020 – APPLICATION FOR EXEMPTION FROM FILING A DULY ATTESTED AFFIDAVIT PAPER BOOK (FOR INDEX: KINDLY SEE INSIDE) ADVOCATE FOR APPLICANTS: Mr. PRASANNA S. S.No Particulars Page Nos. 1. I.A. No. _____ of 2020 1 - 29 Application for Impleadment/Intervention along with Affidavit 2. ANNEXURE-A-1 30 -31 The order of this Hon’ble Court dated 22.07.2020, issuing notice on the Suo Motu Contempt proceedings to the Attorney General for India and to the Alleged Contemnor Mr. Prashant Bhushan 3. ANNEXURE-A-2 32 - 33 A true copy of the tweet dated 28.06.2020 by twitter handle @SaketGokhale 4. ANNEXURE-A-3 34 - 37 A true copy of the Statement dt. 27.07.2020 5. ANNEXURE-A-4 38 - 41 A true copy of the article dated 30.07.2020 as it appeared on barandbench.com 6. ANNEXURE-A-5 42 - 46 A true copy of the article dated 27.07.2020 published in The Hindu written by Justice A.P. Shah, former Chief Justice of the Delhi High Court 7. ANNEXURE-A-6 A true copy of the article dated 27.07.2020 published in The 47 – 51 Hindu written by Mr. -

A Case Study of the Naz Foundation's Campaign to Decriminalize Homosexuality in India Preston G

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Capstone Collection SIT Graduate Institute Winter 12-4-2017 Lessons for Legalizing Love: A Case Study of the Naz Foundation's Campaign to Decriminalize Homosexuality in India Preston G. Johnson SIT Graduate Institute Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/capstones Part of the Civic and Community Engagement Commons, Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Criminal Law Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, History of Gender Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, Law and Gender Commons, Law and Society Commons, Legislation Commons, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, Litigation Commons, Policy Design, Analysis, and Evaluation Commons, Political Science Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, Sexuality and the Law Commons, Social Policy Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, and the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Preston G., "Lessons for Legalizing Love: A Case Study of the Naz Foundation's Campaign to Decriminalize Homosexuality in India" (2017). Capstone Collection. 3063. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/capstones/3063 This Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Graduate Institute at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capstone Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -

Challenges & Opportunities: the Advancement of Human Rights in India Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission June 7, 2016 Testim

Challenges & Opportunities: The Advancement of Human Rights in India Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission June 7, 2016 Testimony by John Sifton, Asia Policy Director, Human Rights Watch Mr. Chairman and members of the committee, Thank you for inviting me to testify today in this well-timed hearing. It was fitting and proper to hold a hearing today to coincide with the arrival in Washington of India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, and on the eve of his historic address to a joint session of Congress. Doing so sends a clear message that while the United States values its improving relationship with India, it remains concerned with India’s human rights record. The Indian government, of course, should be raising its own concerns with the record of the United States on human rights and, speaking as a representative of Human Rights Watch, an international nongovernmental organization that works on over 90 countries worldwide, we encourage Prime Minister Modi to do so. Among the topics he should raise with President Barack Obama are excessive and abusive National Security Agency surveillance practices, discriminatory and excessive use of lethal force by local police, and immigration and asylum practices that violate US obligations under international law. And just as India should be raising its rights concerns with the United States, the US has an important role to play by raising its concerns with India. It is a false claim, made by some in India and the United States, that because India is a democracy and an ally, the United States should remain silent about India’s record.