Virginia Key Beach Park Special Resource Study Report to Congress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

20 Adopted Budget and Multi‐Year Capital Plan Parks, Recreation and Open Spaces FY 2019‐20 Ad

FY 2019 ‐ 20 Adopted Budget and Multi‐Year Capital Plan Parks, Recreation and Open Spaces The Parks, Recreation and Open Spaces (PROS) Department builds, operates, manages and maintains one of the largest and most diverse park systems in the country consisting of over 270 parks and over 13,800 acres of passive and active park lands and natural areas that serve as the front line for resiliency and improved health solutions. The Department’s five strategic objectives and priority areas include fiscal sustainability, placemaking/design excellence, health and fitness, conservation and stewardship and performance excellence. The Department provides opportunities for health, happiness and prosperity for residents and visitors of Miami‐Dade County through the Parks & Open Spaces Master Plan, consisting of a connected system of parks, public spaces, natural and historic resources, greenways, blue‐ways and complete streets, guided by principles of access, equity, beauty, sustainability and multiple benefits. The Department operates as both a countywide park system serving 2.8 million residents and as a local parks department for the unincorporated area serving approximately 1.2 million residents. The Department acquires, plans, designs, constructs, maintains, programs and operates County parks and recreational facilities; provides summer camps, afterschool and weekend programs for youth; manages 44 competitive youth sports program partners; provides programs for active adults, the elderly and people with disabilities; and provides unique experiences at Zoo Miami and seven Heritage Parks: Crandon, Deering Estate, Fruit and Spice, Greynolds, Haulover, Homestead Bayfront and Matheson Hammock Park. Additionally, PROS provides various community recreational opportunities including campgrounds, 17 miles of beaches, 304 ballfields, tennis, volleyball, and basketball courts, an equestrian center, picnic shelters, playgrounds, fitness zones, swimming pools, recreation centers, sports complexes, a gun range and walking and bicycle trails. -

Miami Marine Stadium Boat Ramp

Project Name: Miami Marine Stadium Boat Ramp Permittee/Authorized Entity: City of Miami c/o Daniel Rotenberg, Director DREAM 444 SW 2nd Avenue Miami, Florida 33130 Email: [email protected] Authorized Agent: TYLIN International c/o Sara Gutekunst Email: [email protected] Environmental Resource Permit - Granted State-owned Submerged Lands Authorization – Not Applicable U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Authorization –Separate Corps Authorization Required Permit No.: 13-306513-011-EI Permit Issuance Date: November 28, 2018 Permit Construction Phase Expiration Date: November 28, 2023 Environmental Resource Permit Permit No.: 13-306513-011-EI PROJECT LOCATION The activities authorized by this Permit are located within Biscayne Bay, within the Biscayne Bay Aquatic Preserve, Outstanding Florida Waters, Class III Waters, adjacent to 3501 Rickenbacker Causeway, Miami, (Section 17, Township 54 South, Range 42 East), in Miami-Dade County (Latitude N 25° 44’ 34.35”, Longitude W 80° 10’ 10.43”). Offsite mitigation will occur at various locations within Biscayne Bay Aquatic Preserve. PROJECT DESCRIPTION This permit authorizes the installation of two fixed/floating dock finger piers totaling 1,481 sq. ft, installation of a 60 ft. by 86 ft. (5,160 sq. ft.) boat ramp, and 218 ln. ft. of riprap that extends 6 ft. waterward of MHWL. A portion of the boat ramp is located within the footprint of a previously existing non-functional boat ramp and will be expanded from the historic location. This permit authorizes 4,211 ft² of work in surface waters. The bottom substrate consists of a sandy, silty muck bottom layer with scattered shell and rock along with submerged aquatic vegetation, including seagrass and macroalgae. -

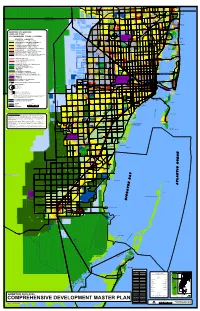

Comprehensive Development Master Plan (CDMP) and Are NAPPER CREEK EXT Delineated in the Adopted Text

E E E A I E E E E E V 1 E V X D 5 V V V V I I V A Y V A 9 A S A A A D E R A 7 I A W 7 2 U 7 7 2 K 7 O 3 7 H W 7 4 5 6 P E W L 7 E 9 W T W N F V W E V 7 W N W N W A W N V 2 A N N 5 N N 7 A 7 S 7 0 1 7 I U 1 1 8 W S DAIRY RD GOLDEN BEACH W SNAKE CREEK CANAL IVE W N N N NW 202 ST AVENTURA BROWARD COUNTY MAN C LEH SWY OMPIAA-MLOI- C K A MIAMI-DADE COUNTY DAWDEES T CAOIRUPNOTYR T NW 186 ST MIAMI GARDENS SUNNY ISLES BEACH E K P T ST W A NE 167 NORTH MIAMI BEACH D NW 170 ST O I NE 163 ST K R SR 826 EXT E E E O OLETA RIVER E V C L V STATE PARK A A H F 0 O 2 1 B 1 ADOPTED 2015 AND 2025 E E E T E N R X N D E LAND USE PLAN * NW 154 ST 9 R Y FIU/BUENA MIAMI LAKES S W VISTA H 1 FOR MIAMI-DADE COUNTY, FLORIDA OPA-LOCKA E AIRPORT I S HAULOVER X U I PARK D RESIDENTIAL COMMUNITIES NW 138 ST OPA-LOCKA W ESTATE DENSITY (EDR) 1-2.5 DU/AC G ESTATE DENSITY W/ ONE DENSITY INCREASE (DI-1) R NORTH MIAMI BAL HARBOUR A T BR LOW DENSITY (LDR) 2.5-6 DU/AC IG OAD N BAY HARBOR ISLANDS HIALEAH GARDENS Y CSW LOW DENSITY W/ ONE DENSITY INCREASE (DI-1) Y AMELIA EARHART PKY E PARK E V E E BISCAYNE PARK E V LOW-MEDIUM DENSITY (LMDR) 6-13 DU/AC V A V V V A D I A A A SURFSIDE MDOC A V 7 M LOW-MEDIUM DENSITY W/ ONE DENSITY INCREASE (DI-1) 2 L 2 7 NORTH 2 1 A B INDIAN CREEK VILLAGE I 2 E E W W E E M W V MEDIUM DENSITY (MDR) 13-25 DU/AC N N N W N V N A N Y NW 106 ST N A 6 MEDIUM DENSITY W/ ONE DENSITY INCREASE (DI-1) A HIALEAH C S E IS N MEDIUM-HIGH DENSITY (MHDR) 25-60 DU/AC N B I MEDLEY L L HIGH DENSITY (HDR) 60-125 DU/AC OR MORE/GROSS AC E MIAMI SHORES O V E C A TWO DENSITY -

Front Desk Concierge Book Table of Contents

FRONT DESK CONCIERGE BOOK TABLE OF CONTENTS I II III HISTORY MUSEUMS DESTINATION 1.1 Miami Beach 2.1 Bass Museum of Art ENTERTAINMENT 1.2 Founding Fathers 2.2 The Wolfsonian 3.1 Miami Metro Zoo 1.3 The Leslie Hotels 2.3 World Erotic Art Museum (WEAM) 3.2 Miami Children’s Museum 1.4 The Nassau Suite Hotel 2.4 Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM) 3.3 Jungle Island 1.5 The Shepley Hotel 2.5 Miami Science Museum 3.4 Rapids Water Park 2.6 Vizcaya Museum & Gardens 3.5 Miami Sea Aquarium 2.7 Frost Art Museum 3.6 Lion Country Safari 2.8 Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) 3.7 Seminole Tribe of Florida 2.9 Lowe Art Museum 3.8 Monkey Jungle 2.10 Flagler Museum 3.9 Venetian Pool 3.10 Everglades Alligator Farm TABLE OF CONTENTS IV V VI VII VIII IX SHOPPING MALLS MOVIE THEATERS PERFORMING CASINO & GAMING SPORTS ACTIVITIES SPORTING EVENTS 4.1 The Shops at Fifth & Alton 5.1 Regal South Beach VENUES 7.1 Magic City Casino 8.1 Tennis 4.2 Lincoln Road Mall 5.2 Miami Beach Cinematheque (Indep.) 7.2 Seminole Hard Rock Casino 8.2 Lap/Swimming Pool 6.1 New World Symphony 9.1 Sunlife Stadium 5.3 O Cinema Miami Beach (Indep.) 7.3 Gulfstream Park Casino 8.3 Basketball 4.3 Bal Harbour Shops 9.2 American Airlines Arena 6.2 The Fillmore Miami Beach 7.4 Hialeah Park Race Track 8.4 Golf 9.3 Marlins Park 6.3 Adrienne Arscht Center 8.5 Biking 9.4 Ice Hockey 6.4 American Airlines Arena 8.6 Rowing 9.5 Crandon Park Tennis Center 6.5 Gusman Center 8.7 Sailing 6.6 Broward Center 8.8 Kayaking 6.7 Hard Rock Live 8.9 Paddleboarding 6.8 BB&T Center 8.10 Snorkeling 8.11 Scuba Diving 8.12 -

Legacy Cove Booklet

The Village Collection at the Grove Unit 1 Unit 2 Unit 3 Unit 4 Ground Floor Total Area 740 738 738 740 reinventED Second Floor Total Area 812 787 787 797 Third Floor Total Area 944 918 918 929 luxury Fourth Floor Total Area 70 70 70 70 Legacy Cove reimagines the Rooftop Terrace 740 730 730 730 Unit Totals town home by boasting Total Area 2,566 2,513 2,513 2,536 contemporary uptown design Total Area w/ Terrace 3,236 3,173 3,173 3,196 on a tranquil street in the coveted neighborhood of Coconut Grove. The Grove offers its inhabitants an UP UP UP UP abundance of dining, night- FOYER FOYER FOYER FOYER life, shopping, art and CAR PORT CAR PORT CAR PORT CAR PORT culture. The residences are 19’-0” x 18’-0” 19’-0” x 18’-0” 19’-0” x 18’-0” 19’-0” x 18’-0” COVERED COVERED COVERED COVERED walking distance from the ENTRY ENTRY ENTRY ENTRY shops and restaurants at Coco Walk, Dinner Key marina, and Peacock Park. GROUND FLOOR Additionally, their convenient location means you’re only a DN DN DN DN GREAT ROOM GREAT ROOM GREAT ROOM GREAT ROOM short drive from Downtown 25’-4” x 16’-10” 25’-4” x 16’-10” 25’-4” x 16’-10” 25’-4” x 16’-10” Miami, Midtown, the beach- es, Kendall, Dadeland and the UP UP UP UP POWDER POWDER POWDER POWDER rest of Miami. ROOM W/D ROOM W/D ROOM W/D ROOM W/D DINING ROOM DINING ROOM DINING ROOM DINING ROOM KITCHEN KITCHEN KITCHEN KITCHEN 13’-4” x 11’-0” 13’-4” x 11’-0” 13’-4” x 11’-0” 13’-4” x 11’-0” Each one of its four dwellings 12’-0” x 11’-9” 12’-0” x 11’-9” 12’-0” x 11’-9” 12’-0” x 11’-9” consist of 3 bedrooms, 2 ½ SECOND FLOOR bathrooms, great room, CLOSET CLOSET CLOSET CLOSET dining room, two-car covered BEDROOM #2 BEDROOM #3 BEDROOM #2 BEDROOM #3 BEDROOM #2 BEDROOM #3 BEDROOM #2 BEDROOM #3 parking, covered entry and a 12’-6” x 11’-0” 10’-6” x 10’-0” 12’-6” x 11’-0” 10’-6” x 10’-0” 12’-6” x 11’-0” 10’-6” x 10’-0” 12’-6” x 11’-0” 10’-6” x 10’-0” CLOSET CLOSET CLOSET CLOSET spacious rooftop terrace for BATH #2 BATH #2 BATH #2 BATH #2 entertaining under the hues UP UP UP UP DN MASTER DN MASTER DN MASTER DN MASTER of a South Florida sunset. -

Countermeasures for Pedestrian and Bicycle High Crash Locations

June 2016 APPENDIX A PRESENTATIONS Local Action Team for Safer People, Safer Streets 6/1/2016 Study Goals • Develop multi-disciplinary strategies to reduce traffic crashes involving pedestrians and bicyclists. • Develop an on-going process for continuing safety monitoring, analysis and improvement. 1 6/1/2016 Miami-Dade’s Traffic Safety Problem • Florida’s pedestrian and bicycle fatality rates are among the highest in the US. • Miami-Dade County has the highest number of pedestrian and bicycle crashes in Florida. Source: DHSMV Pedestrian Crashes 2 6/1/2016 Pedestrian Crashes (2008-2013) Year Crashes 2008 1,307 2009 1,301 2010 1,207 2011 962 2012 1,089 2013 1,162 Total 7,028 2008-2013 • Pedestrian crashes declined each year between 2008 and 2011 but have increased in 2012 and 2013. Pedestrian Crash Density 3 6/1/2016 High Pedestrian Crash Locations Example: Miami Juvenile pedestrians (18%) 4 6/1/2016 Fatal Pedestrian Crashes (2008-2013) Year Fatal Crashes 2008 64 2009 65 2010 75 2011 68 2012 47 2013 68 2008-2013 Total 388 On average, 1 in 18 crashes involving a pedestrian resulted in a fatality. 5 6/1/2016 Elderly pedestrians (33%) Lighting Condition Labels: Number of Crashes (Percentage) 6 6/1/2016 Impairment Labels: Number of Crashes (Percentage) Speed Limit vs. Pedestrian Injury Severity 1 0.8 Fatal n o i Incapacitating t 0.6 r o p injury o r P y Non-incapacitating t i r e injury v 0.4 e S No injury 0.2 The risk of a pedestrian crash being a fatal crash is three times greater 0 on 45 mph roads in comparison to 25 30 35 40 45 50 or higher 30 mph roads. -

Virginia Key Beach County Park

South Florida Geological Site Guide series Department of Earth Sciences Florida International University, University Park, SW 8th Street & 107 Avenue, Miami, FL 33199 www.fiu.edu/~geology No. 03 VIRGINIA KEY BEACH COUNTY PARK (v.1.0, 5-06) Prepared by Grenville Draper Department of Earth Sciences Location and access Take the Rickenbacker Causeway as if going to the beaches on Key Biscayne. Just after passing the Seaquarium (and just before the bridge to Key Biscayne), turn left on the road that leads to the water treatment plant and the parking area for Virginia Key beach. (Unless you have made prior arrangements, you will have to pay the entrance fee to the park). Continue until the fork in the road, then turn right into the parking area. What there is to see Aspects of beach dynamics and erosion. Backround Like Miami Beach and Key Biscayne, Virginia Key is a sedimentary barrier island. Virginia Key and Key Biscayne are parts of the barrier island system which stretches along most of the coast of southeastern Florida. About 20,000 years ago, a glacial period ended and the climate began to warm. During the glacial period, sea level had been as much as 100m. (300 ft.) below present sea level. As the climate warmed, sea level started to rise to its present level. It is from this period that the barrier islands of Miami Beach, Virginia Key, and Key Biscayne began to be formed. Sediments were carried by longshore currents, and consisted of a mixture of carbonate (shell fragments, coral fragments, etc.) and quartz sand. -

Jim Crow at the Beach: an Oral and Archival History of the Segregated Past at Homestead Bayfront Park

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Biscayne National Park Jim Crow at the Beach: An Oral and Archival History of the Segregated Past at Homestead Bayfront Park. ON THE COVER Biscayne National Park’s Visitor Center harbor, former site of the “Black Beach” at the once-segregated Homestead Bayfront Park. Photo by Biscayne National Park Jim Crow at the Beach: An Oral and Archival History of the Segregated Past at Homestead Bayfront Park. BISC Acc. 413. Iyshia Lowman, University of South Florida National Park Service Biscayne National Park 9700 SW 328th St. Homestead, FL 33033 December, 2012 U.S. Department of the InteriorNational Park Service Biscayne National Park Homestead, FL Contents Figures............................................................................................................................................ iii Acknowledgments.......................................................................................................................... iv Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 A Period in Time ............................................................................................................................. 1 The Long Road to Segregation ....................................................................................................... 4 At the Swimming Hole .................................................................................................................. -

On the Move... Miami-Dade County's Pocket

Guide Cover 2013_English_Final.pdf 1 10/3/2013 11:24:14 AM 111 NW First Street, Suite 920 Miami, FL 33128 tel: (305) 375-4507 fax: (305) 347-4950 www.miamidade.gov/mpo C M On the Y CM MY Move... CY CMY K Miami-Dade County’s Pocket Guide to Transportation Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) 4th Edition Table of Contents Highway Information Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) p. 1 FDOT’s Turnpike Enterprise p. 2 Florida Highway Patrol p. 2 95 Express Lanes p. 3 Miami-Dade Expressway Authority (MDX) p. 4 SunPass® p. 5 511-SmarTraveler p. 5 Road Rangers p. 5 SunGuide® Transportation Management Center p. 6 Miami-Dade Public Works and Waste p. 7 Management Department Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) p. 8 Driving and Traffic Regulations p. 8 Three Steps for New Florida Residents p. 9 Drivers License: Know Before You Go p. 9 Vehicle Registration p. 10 Locations and Hours of Local DMV Offices p. 10-11 Transit Information Miami-Dade Transit (MDT) p. 12 Metrobus, Metrorail, Metromover p. 12 Fares p. 13 EASY Card p. 13 Discount EASY Cards p. 14-15 Obtaining EASY Card or EASY Ticket p. 15 Transfers p. 16-17 Park and Ride Lots p. 17-18 Limited Stop Route/Express Buses p. 18-19 Special Transportation Services (STS) p. 20 Special Event Shuttles p. 21 Tax-Free Transit Benefits p. 21 I Transit Information (Continued) South Florida Regional Transportation Authority p. 22 (SFRTA) / TriRail Amtrak p. 23 Greyhound p. 23 Fare & Schedule Information p. 24 Local Stations p. -

Downtown's Major Events

Downtown’s Major Events – By Month January: Miami Cruise Month | www.miamiandbeaches.com Take advantage of exciting program features and enticing special offers all month long including Pre-cruise Miami hotel stays, attraction visits, pre- and post-cruise heritage tours and much more. Miami Marathon | January 29, 2017 | www.themiamimarathon.com Every year over 25,000 runners take to the streets of Miami for the Miami Marathon and Half Marathon (previously the ING Miami Marathon.) The Miami Marathon & Half Marathon takes you through the streets of Miami starting in the downtown area, to the scenic beaches, through the art district and back around to our lovely bay area. (Estimated 2018 Date – 1/28/18) February: Miami Romance Month | www.miamiromancemonth.com Greater Miami and the Beaches - the perfect place to spark a new romance, rekindle an old flame or tie the knot. During Miami Romance Month take advantage of special offers from shopping to dining to couples getaways, events and more. Miami International Map Fair at HistoryMiami | February 3-5, 2017 | www.historymiami.org This annual event showcases antique maps, rare books, panoramas and atlases from around the world. Peruse and purchase antique maps from some of the finest map dealers in the world and discover the history and future of cartography with dynamic speakers. (Estimated 2018 Date – 2/2-4/18) Miami International Boat Show | February 16-20, 2017 | www.miamiboatshow.com See what’s new at the Greatest Boat Show in the World! Florida's largest annual event spans two locations—the Miami Marine Stadium Park & Basin on Virginia Key and Strictly Sail® at Miamarina at Bayside—and features more than 3,000 boats and 2,000 exhibitors from all over the globe. -

N O W L a U N C H I N

BOAT SHOW INSIDER By Kim Kavin NOW LAUNCHING: MIAMI 2.0 athy rick-joule looked at the letter. She blinked. Again. She’d spent two decades managing the Miami International Boat Show for the National Marine Manufacturers Association, and she’d heard rumblings about the city wanting to renovate the nearly 60-year-old Miami Beach Convention Center. The boat Cshow had been held there since 1969. It had endured the renovation in the 1980s. “We thought this would be very similar,” she says. Until she received that letter. “It said, ‘Just letting you know, we’ll be reaching out to talk about the renovation — and oh, by the Virginia Key will be the new home of the Progressive Insurance Miami International Boat Show for 2016. 64 YACHTING FEBRUARY 2016 BOAT SHOW INSIDER Miami 2.0 BISCAYNE BAY 3. YACHTS MIAMI BEACH On Collins Avenue 41st - 54th streets 4. SUPERYACHT MIAMI building 2. a new marina STRICTLY Pennsylvania-based SAIL Bellingham Marine is building SOUTH BEACH the all-new, tempo- rary marina that will host the Progressive way, there’s a list of shows that will be protected While the new show will be about the same size Insurance Miami during construction,’” she says. “And the boat show as the convention-center version — about a million International Boat Show at Virginia Key. wasn’t on this list.” square feet — a greater amount of the space will be Special attention The $500 million renovation would not be done in-water displays. Around 440 boats will be in the is being paid to the until 2018. -

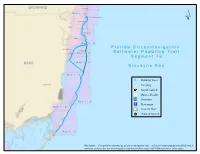

Segment 16 Map Book

Hollywood BROWARD Hallandale M aa p 44 -- B North Miami Beach North Miami Hialeah Miami Beach Miami M aa p 44 -- B South Miami F ll o r ii d a C ii r c u m n a v ii g a tt ii o n Key Biscayne Coral Gables M aa p 33 -- B S a ll tt w a tt e r P a d d ll ii n g T r a ii ll S e g m e n tt 1 6 DADE M aa p 33 -- A B ii s c a y n e B a y M aa p 22 -- B Drinking Water Homestead Camping Kayak Launch Shower Facility Restroom M aa p 22 -- A Restaurant M aa p 11 -- B Grocery Store Point of Interest M aa p 11 -- A Disclaimer: This guide is intended as an aid to navigation only. A Gobal Positioning System (GPS) unit is required, and persons are encouraged to supplement these maps with NOAA charts or other maps. Segment 16: Biscayne Bay Little Pumpkin Creek Map 1 B Pumpkin Key Card Point Little Angelfish Creek C A Snapper Point R Card Sound D 12 S O 6 U 3 N 6 6 18 D R Dispatch Creek D 12 Biscayne Bay Aquatic Preserve 3 ´ Ocean Reef Harbor 12 Wednesday Point 12 Card Point Cut 12 Card Bank 12 5 18 0 9 6 3 R C New Mahogany Hammock State Botanical Site 12 6 Cormorant Point Crocodile Lake CR- 905A 12 6 Key Largo Hammock Botanical State Park Mosquito Creek Crocodile Lake National Wildlife Refuge Dynamite Docks 3 6 18 6 North Key Largo 12 30 Steamboat Creek John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park Carysfort Yacht Harbor 18 12 D R D 3 N U O S 12 D R A 12 C 18 Basin Hills Elizabeth, Point 3 12 12 12 0 0.5 1 2 Miles 3 6 12 12 3 12 6 12 Segment 16: Biscayne Bay 3 6 Map 1 A 12 12 3 6 ´ Thursday Point Largo Point 6 Mary, Point 12 D R 6 D N U 3 O S D R S A R C John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park 5 18 3 12 B Garden Cove Campsite Snake Point Garden Cove Upper Sound Point 6 Sexton Cove 18 Rattlesnake Key Stellrecht Point Key Largo 3 Sound Point T A Y L 12 O 3 R 18 D Whitmore Bight Y R W H S A 18 E S Anglers Park R 18 E V O Willie, Point Largo Sound N: 25.1248 | W: -80.4042 op t[ D A I* R A John Pennekamp State Park A M 12 B N: 25.1730 | W: -80.3654 t[ O L 0 Radabo0b.