Sharing Information to Strengthen Rural Communities: Lessons Learned from BC Projects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Definitions of Rural

Rural and Small Town Canada Analysis Bulletin Catalogue no. 21-006-XIE Vol. 3, No. 3 (November 2001) DEFINITIONS OF RURAL Valerie du Plessis, Roland Beshiri and Ray D. Bollman, Statistics Canada and Heather Clemenson, Rural Secretariat, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada HIGHLIGHTS ¨ Several alternative definitions of “rural” are available for national level policy analysis in Canada. ¨ For each rural issue, analysts should consider whether it is a local, community or regional issue. This will influence the type of territorial unit upon which to focus the analysis and the appropriate definition to use. ¨ Different definitions generate a different number of “rural” people. ¨ Even if the number of “rural” people is the same, different people will be classified as “rural” within each definition. ¨ Though the characteristics of “rural” people are different for each definition of “rural”, in general, each definition provides a similar analytical conclusion. Our recommendation We strongly suggest that the appropriate definition should be determined by the question being addressed; however, if we were to recommend one definition as a starting point or benchmark for understanding Canada’s rural population, it would be the “rural and small town” definition. This is the population living in towns and municipalities outside the commuting zone of larger urban centres (i.e. outside the commuting zone of centres with population of 10,000 or more). Rural and Small Town Canada Analysis Bulletin, Vol. 3, No. 3 Rural and Small Town Canada Analysis Bulletin ISSN 1481-0964 Editor: Ray D. Bollman ([email protected]) Tel.: (613) 951-3747 Fax: (613) 951-3868 Published in collaboration with The Rural Secretariat, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. -

Plan Employers

Plan Employers 18th Street Community Care Society 211 British Columbia Services Society 28th Avenue Homes Ltd 4347 Investments Ltd. dba Point Grey Private Hospital 484017 BC Ltd (dba Kimbelee Place) 577681 BC Ltd. dba Lakeshore Care Centre A Abilities Community Services Acacia Ty Mawr Holdings Ltd Access Human Resources Inc Active Care Youth and Adult Services Ltd Active Support Against Poverty Housing Society Active Support Against Poverty Society Age Care Investment (BC) Ltd AIDS Vancouver Society AiMHi—Prince George Association for Community Living Alberni Community and Women’s Services Society Alberni-Clayoquot Continuing Care Society Alberni-Clayoquot Regional District Alouette Addiction Services Society Amata Transition House Society Ambulance Paramedics of British Columbia CUPE Local 873 Ann Davis Transition Society Archway Community Services Society Archway Society for Domestic Peace Arcus Community Resources Ltd Updated September 30, 2021 Plan Employers Argyll Lodge Ltd Armstrong/ Spallumcheen Parks & Recreation Arrow and Slocan Lakes Community Services Arrowsmith Health Care 2011 Society Art Gallery of Greater Victoria Arvand Investment Corporation (Britannia Lodge) ASK Wellness Society Association of Neighbourhood Houses of British Columbia AVI Health & Community Services Society Avonlea Care Centre Ltd AWAC—An Association Advocating for Women and Children AXIS Family Resources Ltd AXR Operating (BC) LP Azimuth Health Program Management Ltd (Barberry Lodge) B BC Council for Families BC Family Hearing Resource Society BC Institute -

Zone 12 - Northern Interior and Prince George

AFFORDABLE HOUSING Choices for Seniors and Adults with Disabilities Zone 12 - Northern Interior and Prince George The Housing Listings is a resource directory of affordable housing in British Columbia and divides British Columbia into 12 zones. Zone 12 identifies affordable housing in the Northern Interior and Prince George. The attached listings are divided into two sections. Section #1: Apply to The Housing Registry Section 1 - Lists developments that The Housing Registry accepts applications for. These developments are either managed by BC Housing, Non-Profit societies, or Co- Operatives. To apply for these developments, please complete an application form which is available from any BC Housing office, or download the form from www.bchousing.org/housing- assistance/rental-housing/subsidized-housing. Section #2: Apply directly to Non-Profit Societies and Housing Co-ops Section 2 - Lists developments managed by non-profit societies or co-operatives which maintain and fill vacancies from their own applicant lists. To apply for these developments, please contact the society or co-op using the information provided under "To Apply". Please note, some non-profits and co-ops close their applicant list if they reach a maximum number of applicants. In order to increase your chances of obtaining housing it is recommended that you apply for several locations at once. Housing for Seniors and Adults with Disabilities, Zone 12 - Northern Interior and Prince George August 2020 AFFORDABLE HOUSING SectionSection 1:1: ApplyApply toto TheThe HousingHousing RegistryRegistry forfor developmentsdevelopments inin thisthis section.section. Apply by calling 250-562-9251 or, from outside Prince George, 1-800-667-1235. -

Points of Service

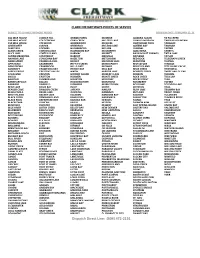

CLARK FREIGHTWAYS POINTS OF SERVICE SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE REVISION DATE: FEBRUARY 12, 21 100 MILE HOUSE COBBLE HILL GRAND FORKS MCBRIDE QUADRA ISLAND TA TA CREEK 108 MILE HOUSE COLDSTREAM GRAY CREEK MCLEESE LAKE QUALICUM BEACH TABOUR MOUNTAIN 150 MILE HOUSE COLWOOD GREENWOOD MCGUIRE QUATHIASKI COVE TADANAC AINSWORTH COMOX GRINDROD MCLEOD LAKE QUEENS BAY TAGHUM ALERT BAY COOMBS HAGENSBORG MCLURE QUESNEL TAPPEN ALEXIS CREEK CORDOVA BAY HALFMOON BAY MCMURPHY QUILCHENA TARRY'S ALICE LAKE CORTES ISLAND HARMAC MERRITT RADIUM HOT SPRINGS TATLA LAKE ALPINE MEADOWS COURTENAY HARROP MERVILLE RAYLEIGH TAYLOR ANAHIM LAKE COWICHAN BAY HAZELTON METCHOSIN RED ROCK TELEGRAPH CREEK ANGELMONT CRAIGELLA CHIE HEDLEY MEZIADIN LAKE REDSTONE TELKWA APPLEDALE CRANBERRY HEFFLEY CREEK MIDDLEPOINT REVELSTOKE TERRACE ARMSTRONG CRANBROOK HELLS GATE MIDWAY RIDLEY ISLAND TETE JAUNE CACHE ASHCROFT CRAWFORD BAY HERIOT BAY MILL BAY RISKE CREEK THORNHILL ASPEN GROVE CRESCENT VALLEY HIXON MIRROR LAKE ROBERTS CREEK THREE VALLEY GAP ATHALMER CRESTON HORNBY ISLAND MOBERLY LAKE ROBSON THRUMS AVOLA CROFTON HOSMER MONTE CREEK ROCK CREEK TILLICUM BALFOUR CUMBERLAND HOUSTON MONTNEY ROCKY POINT TLELL BARNHARTVALE DALLAS HUDSONS HOPE MONTROSE ROSEBERRY TOFINO BARRIERE DARFIELD IVERMERE MORICETOWN ROSSLAND TOTOGGA LAKE BEAR LAKE DAVIS BAY ISKUT MOYIE ROYSTON TRAIL BEAVER COVE DAWSON CREEK JAFFARY NAKUSP RUBY LAKE TRIUMPH BAY BELLA COOLA DEASE LAKE JUSKATLA NANAIMO RUTLAND TROUT CREEK BIRCH ISLAND DECKER LAKE KALEDEN NANOOSE BAY SAANICH TULAMEEN BLACK CREEK DENMAN ISLAND -

West Kootenay Women's Association/ 420 Mill Street

WEST KOOTENAY WOMEN'S ASSOCIATION/ 420 MILL STREET. NELSON. B.C. VIL 4R9 (250)352-9916 • FAX* (250) 352-7100 March 3, 1999 The Honourable Penny Priddy Minister of Health Room 133, Parliament Buildings Victoria, British Columbia V8V 1X4 Fax:(250)387-3696 Dear Minister Priddy: We at the Nelson and District Women's Centre / West Kootenay Women's Association are very concerned about the pending termination of funding for ANKORS' Needle Exchange and Client Services programs. Both of these services are considered essential in urban areas and have been extremely successful here, exceeding all initial projections. Both operate at a fraction of the cost of their urban counterparts - yet both are slated to shut down at the end of March, 1999. Does the Ministry of Health consider that Needle Exchange and Client Services are less essential for people in rural areas who risk contracting, or are living with, HIV? ANKORS provides the only comprehensive HIV and AIDS education, prevention, care, treatment referral and support services for the West Kootenay - Boundary region. Such programs are available through a variety of agencies in urban areas and we would like your assurance that these vital services will be sustained in our rural communities as well. We urge your Ministry to recognize that HIV and AIDS are not only an urban concern. Provide funding for ANKORS to continue these two important programs. Rural health care matters! Thank you for your prompt attention to this urgent concern. Sincerely, Karen Newmoon Rhonda Schmidt Coordinator Chair Nelson & District Women's Centre West Kootenay Women's Association Cc: Ms. -

Pages 16 & 17 Kaslo City Hall National Historic Site Re-Opens

August 9, 2018 The Valley Voice 1 CHRISTINA HARDER Your Local Real Estate Professional Volume 27, Number 16 August 9, 2018 Delivered to every home between Edgewood, Kaslo & South Slocan. Office 250-226-7007 Published bi-weekly. Cell 250-777-3888 Your independently owned regional community newspaper serving the Arrow Lakes, Slocan & North Kootenay Lake Valleys Kaslo City Hall National Historic Site re-opens by Jan McMurray The stone work around the foundation CAO Neil Smith points out Also, it will be one of the properties Canada, BC Heritage Legacy Fund, Kaslo’s 1898 City Hall building was repointed, the wood siding boards that the offices have also been to benefit from the sewer collection Community Works Funds and other re-opened July 23 after being closed were refurbished or replaced, the modernized for the 21st century, with system expansion. programs. for restoration and renovations for circular entrance stairway and the telecommunications fibre broadband The Village accessed considerable Kaslo City Hall is one of only almost nine years. The makeover was south side stairway were rebuilt, and and VOIP services telephone made funding support for the project three municipal buildings in BC that well worth the wait – this National a wheelchair ramp was added. possible by the Kaslo infoNet Society. from Columbia Basin Trust, Parks are National Historic Sites. Historic Site is looking very good indeed. “It’s a happy coincidence that 2018 is both the community’s 125th anniversary and a new chapter in the life of City Hall,” said Chief Administrative Officer Neil Smith. The “happy coincidence” doesn’t stop at the year, though. -

The Valley Voice Is 100% Locally Owned and Operated Corky Says

April 8, 2009 The Valley Voice 1 Volume 18, Number 7 April 8, 2009 Delivered to every home between Edgewood, Kaslo & South Slocan. Published bi-weekly. “Your independently owned regional community newspaper serving the Arrow Lakes, Slocan & North Kootenay Lake Valleys.” Corky says farewell as our MLA at ‘Celebrating Corky’ roast and toast event by Jan McMurray yellow fisherman’s rain hat, Luscombe She announced that she and her husband said. “Leadership is what you choose to me. When we got creamed, we got a MLA Corky Evans was roasted and toasted Corky with a healthy dose of Ed had decided to give him a retirement represent your values.” resurrection team together. I ask you to toasted on April 4 at Mary Hall, the same Screech. gift of a truckload of manure – “the In closing, Corky said, “You pass it on, keep it going, because the rest venue where he was first nominated Bill Lynch, Corky’s first campaign best darn bull shit you’ll ever get,” she invented me and then you supported of the world needs it.” as the NDP candidate for our riding in manager, described Corky as “a deeply chided. 1986. Corky is retiring on May 12 to moral human being who did politics Then it was Corky. This speech was the life of a farmer and beekeeper on that way.” probably one of the most emotional of his property in Winlaw. Karen Hamling, Mayor of Nakusp, his life. “There’s a sign outside that says The evening started off with an said that the three years Corky spent ‘Celebrate Corky,’” he began. -

Education, Place, and the Sustainability of Rural Communities

Journal ofResearch in Rural Education, Winter, 1998, Vol. 14, No.3, 131-141 E(Qlu.n(c21~fi~rm9 JIDll21(C<e92lrm(Ql ~Ihl<e §u.n§mfirm21bfillfi~y ~f JRu.nJr21ll <C~mmu.nrmfi1fi<e§ firm §21§lk21~(CIhl<ew21rm Terry Wotherspoon University ofSaskatchewan Schools which have long been cornerstones ofsustainability for rural communities are in danger ofdisappearing in many areas that rely on agriculture as the primary industry. Many forecasters project the demise ofrural schooling and the communities the schools serve amidst global pressures to concentrate and centralize economic production, jobs, and services. Other commentators argue that rural schools can playa vital role infostering a sense ofplace that is critical to the development ofmeaningful social, economic, and cultural opportunities in uniquely situated communities. This paper examines the perceptions about schooling's contributions to community sustainability held by southwestern Saskatchewan residents. In the face ofpressures to close and consolidate many community schools, area residents place a high value on the maintenance ofextensive local educational services, are generally satisfied with the services available to them, and contribute actively to support schooling. However, schools offer credentials and content that serve urban centres more than local communities. If schools are to remain vital to rural community sustainability, educators, policymakers, and community members must offer strategies that link education with the development ofeconomic diversification, meaning ful jobs, and supportive community infrastructures. Introduction tion and the introduction of advanced communications tech nologies have made these regions less isolated than once The phenomena of education, work, and community was the case. On the other hand, increasing concentrations sustainability traditionally act in a complementary man of resources and services in metropolitan regions have posed ner. -

BC HYDRO with All New Gi,Tech Design Is Herd MOLSOHCANADIAN MCALPINE& CO

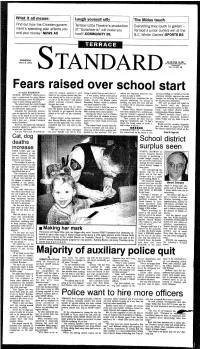

What it all means: Laugh yourself silly The Midas touch Find out how the Chretien govern- Terrace Little Theatre's production Everything they touch is golden - ment's spending plan affects you of "Suitehearts" will make you Terrace's junior curlers win at the and your money.kNEW$ A5 howI!\COMMUNITY B1 B.C. Winter Games\SPORTS !]5 WEDNESDAY March 8, 2000 $1.00 PLUS 7¢ GST mm m m ($1.10 plus 8¢ GST outside of the T, N DA o11 Jl__J VOL.'--'- 12 NO. Fears raised over school start By ALEX HAMILTON cause the ministry approval is still trying to track it but we can't find it." school was originally slated for com- on hold, pending on whether or not the SCHOOL DISTRICT administrators based on the original motion that [the A new school, which could cost as pletion as early as 2003. education minister approves the new hope a replacement for aging Skeena new school] will be built on the Skee- much as $11.6-million, is needed to Administrators completed the pa- location for building the replacement Junior Secondary won't be delayed be- na site or on the bench," said school replace 45-year old Skeena Junior perwork explaining the change in for Skeena Junior Secondary. cause of some missing paperwork. district secretary treasurer Marcel Secondary School, which is rundown building site plans last week and had "We can't go ahead and build on The school board last April chan~ed Georges last week. and needs extensive work. it rushed off to education minister its mind on where it wanted to build the bench until the Skeena "Regrettably there was no letter Trustees voted to build the new re- Penny Priddy. -

Municipalities in Alberta Types of Municipalities and Other Local Authorities

Learn About Municipal Government Municipalities in Alberta Types of municipalities and other local authorities Towns Types of Municipal Governments A town can be formed with a minimum population of in Alberta 1,000 people and may exceed 10,000 people unless a request to change to city status is made. Under Alberta is governed through three general types of the MGA, a town is governed by a seven-member municipalities: urban, rural and specialized. Urban council. However, a local bylaw can change the municipalities are summer villages, villages, towns, number of council members to be higher or lower, as and cities. Rural municipalities include counties and long as that number is no lower than three and municipal districts. Specialized municipalities can remains at an odd number. The chief elected official include both rural and urban communities. for a town is the mayor. Key Terms Villages Mayor: the title given to the person elected as the head or chair of the municipal council. Also called A village may be formed in an area where the the chief elected official. Generally used in urban majority of buildings are on parcels of land smaller municipalities, but is used by some rural than 1,850 square meters and there is a population municipalities. of at least 300 people. A village may apply for town Reeve: the title given to the person elected as the status when the population reaches 1,000; it does head or chair of the municipal council. Also called not lose its village status if the population declines the chief elected official. -

Order in Council 1371/1994

PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA ORDER OF THE LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR IN COUNCIL Order in Council No. 1371 , Approved and Ordered CV 171994 Lieutenant Governor Executive Council Chambers, Victoria On the recommendation of the undersigned, the Lieutenant Governor, by and with the advice and consent of the Executive Council, orders that I. Where a minister named in column 2 of the attached Schedule is (a) unable through illness to perform the duties of his or her office named in Column 1, (b) absent from the capital, or (c) unable by reason of section 9.1 of the Members' Conflict of Interest Act to perform some or all of the duties of his or her ()Lice, the minister named opposite that office in Column 3 is aptminted- acting minister. 2. Where the acting minister is also unable through illness, absence from the capital or by reason of section 9.1 of the Members' Conflict of Interest Act to perform the duties, the minister named opposite in Column 4 is appointed acting minister. 3. Appointments of acting ministers made by Order in Council 1499/93 are rescinded. 21 Presiding Member of the Executive Council ( Thts port is for atinunt tiranve purpose! only and in not port of the Order I Authority under which Order is made: Act and section:- Constitution Act, sections 10 to 14 Other (specify):- Members' Conflict of Interest, section 9.1 (2) c.,1C H-99 v November 3, 1994 a .9i i' )-11.99- 23v2., /93/88/aaa u0 • (1---1 n;ot Schedule 1 Column 1 Column 2 Column 3 Column 4 Ministry Minister First Acting Minister Second Acting Minister Premier Michael Harcourt Elizabeth Cull Andrew Pester Aboriginal Affairs John Cashore Andrew Petter Moe Sihota Agriculture. -

Rural and Small Town Canada Analysis Bulletin Catalogue No

Rural and Small Town Canada Analysis Bulletin Catalogue no. 21-006-X Vol. 8, No. 3 (January 2010) Standing Firm: Rural Business Enterprises in Canada Neil Rothwell, Statistics Canada Highlights • In 2007, rural and small town Canada had slightly more firms per capita compared to Canada’s larger urban centres. • In 2007, rural and small town Canada had a higher share of firms with 1 to 4 employees compared to Canada as a whole. • Rural and small town Canada may have relatively more firms and a higher share of firms with 1 to 4 employees due to the dispersed nature and smaller size of its communities. This pattern tends to encourage the establishment of more but smaller firms. • Communities in weak metropolitan influenced zones (Weak MIZ) appear to be classified as weakly influenced by larger urban centres because they often serve as regional service centres. Among the MIZs, Weak MIZ has relatively more producer service firms (albeit still well under the Canadian average) and more firms with over 200 employees (again, still well under the Canadian average). Introduction Within Canada, the economic vitality of those employment (Sorensen and de Peuter, 2005). areas outside of major urban areas is of increasing However, outside of the oil and gas sector, it is concern. Without the large population bases that precisely these areas of employment that have drive service sector employment, these areas have been particularly subject to global competition tended to rely more on resource oriented primary and have come under increasing pressure in recent industry, manufacturing and producer services times. The drive to become more efficient and Rural and Small Town Canada Analysis Bulletin, Vol.