The Earthwork Remains of Enclosure in the New Forest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Consultation Statement New Forest National Park Local Plan 2016

Consultation Statement New Forest National Park Local Plan 2016 - 2036 May 2018 1. Introduction 1.1 The New Forest National Park Authority is undertaking a review of the local planning policies covering the National Park – currently contained within the Core Strategy & Development Management Policies DPD (adopted December 2010). This review is in response to changes in national policy and the experiences of applying the adopted planning policies for the past 7 years. The review will result in the production of a revised Local Plan covering the whole of the National Park. 1.2 The revised Local Plan will form a key part of the statutory ‘development plan’ for the National Park and will ultimately guide decisions on planning applications submitted within the Park. The Local Plan will set out how the planning system can contribute towards the vision for the New Forest National Park in 2036 and will include detailed planning policies and allocations that seek to deliver the two statutory National Park purposes and related socio-economic duty. 1.3 This Statement is a record of the consultation undertaken during the Local Plan- making process which started in 2015. As required by Regulation 22 of the Town and Country (Local Planning) (England) Regulations 2012, it sets out who has been invited to make representations on the Local Plan; summarises the main issues raised; and how they have been taken into account during the development of the Plan. The Statement covers the Regulation 18 consultation on the scope and main issues to be covered in the Local Plan review; the public consultation on the non- statutory draft Local Plan published in October 2016; the subsequent consultation on potential alternative housing sites undertaken in June – July 2017; and finally the statutory 6-week public consultation on the proposed Submission draft Local Plan in January and February 2018 (Regulation 19). -

Girlguiding Hampshire West Unit Structure As at 16 April 2019 Division District Unit Chandlers Ford Division 10Th Chandlers Ford

Girlguiding Hampshire West Unit structure as at 16 April 2019 Division District Unit Chandlers Ford Division 10th Chandlers Ford Brownie Unit Chandlers Ford Division 14th Chandlers Ford Brownie Unit Chandlers Ford Division 14th Chandlers Ford Rainbow Unit Chandlers Ford Division 1st Chandlers Ford Brownie Unit Chandlers Ford Division 1st Chandlers Ford Div Rgu Senior Section Unit Chandlers Ford Division 1st Chandlers Ford Guide Unit Chandlers Ford Division 1st Chandlers Ford Ramalley Brownie Unit Chandlers Ford Division 1st Chandlers Ford Ramalley Guide Unit Chandlers Ford Division 1st Chandlers Ford West Rainbow Unit Chandlers Ford Division 2nd Chandlers Ford Ramalley (Formerly 2nd Chandlers Ford) Guide Unit Chandlers Ford Division 2nd Chandlers Ford Ramalley Brownie Unit Chandlers Ford Division 2nd Chandlers Ford Ramalley Rainbow Unit Chandlers Ford Division 2nd Ramalley (Chandlers Ford) Senior Section Unit Chandlers Ford Division 3rd Chandlers Ford Ramalley Brownie Unit Chandlers Ford Division 4th Chandlers Ford Brownie Unit Chandlers Ford Division 4th Chandlers Ford Guide Unit Chandlers Ford Division 4th Chandlers Ford Ramalley Coy Guide Unit Chandlers Ford Division 4th Chandlers Ford S Rainbow Unit Chandlers Ford Division 4th Chandlers Ford Senior Section Unit Chandlers Ford Division 5th Chandlers Ford Brownie Unit Chandlers Ford Division 5th Chandlers Ford Rainbow Unit Chandlers Ford Division 6th Chandlers Ford Guide Unit Chandlers Ford Division 8th Chandlers Ford Brownie Unit Chandlers Ford Division 9th Chandlers Ford Brownie Unit -

Parish Enforcement List and Closed Cases NEW FOREST NATIONAL PARK AUTHORITY ENFORCEMENT CONTROL Enforcement Parish List for Beaulieu 02 April 2019

New Forest National Park Authority - Enforcement Control Data Date: 02/04/2019 Parish Enforcement List and Closed Cases NEW FOREST NATIONAL PARK AUTHORITY ENFORCEMENT CONTROL Enforcement Parish List for Beaulieu 02 April 2019 Case Number: QU/19/0030 Case Officer: Lucie Cooper Unauthorised Change Of Use (other) Date Received: 24/1/2019 Type of Breach: Location: HILLTOP NURSERY, HILL TOP, BEAULIEU, BROCKENHURST, SO42 7YR Description: Unauthorised change of use of buildings Case Status: Further investigation being conducted Priority: Standard Case Number: QU/18/0181 Case Officer: Lucie Cooper Unauthorised Operational Development Date Received: 11/10/2018 Type of Breach: Location: Land at Hartford Wood (known as The Ropes Course), Beaulieu Description: Hardstanding/enlargement of parking area Case Status: Retrospective Application Invited Priority: Standard Case Number: CM/18/0073 Case Officer: David Williams Compliance Monitoring Date Received: 18/4/2018 Type of Breach: Location: THORNS BEACH HOUSE, THORNS BEACH, BEAULIEU, BROCKENHURST, SO42 7XN Description: Compliance Monitoring - PP 17/00335 Case Status: Site being monitored Priority: Low 2 NEW FOREST NATIONAL PARK AUTHORITY ENFORCEMENT CONTROL Enforcement Parish List for Boldre 02 April 2019 Case Number: QU/19/0051 Case Officer: Katherine Pullen Unauthorised Change Of Use (other) Date Received: 26/2/2019 Type of Breach: Location: Newells Copse, off Snooks Lane, Walhampton, Lymington, SO41 5SF Description: Unauthorised change of use - Use of land for motorcycle racing Case Status: Planning Contravention Notice Issued Priority: Low Case Number: QU/18/0212 Case Officer: Lucie Cooper Unauthorised Operational Development Date Received: 29/11/2018 Type of Breach: Location: JAN RUIS NURSERIES, SHIRLEY HOLMS ROAD, BOLDRE, LYMINGTON, SO41 8NG Description: Polytunnel/s; Erection of a storage building. -

Buddles Corner, Fritham, Lyndhurst SO43

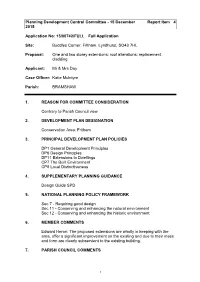

Planning Development Control Committee - 15 December Report Item 4 2015 Application No: 15/00742/FULL Full Application Site: Buddles Corner, Fritham, Lyndhurst, SO43 7HL Proposal: One and two storey extensions; roof alterations; replacement cladding Applicant: Mr & Mrs Day Case Officer: Katie McIntyre Parish: BRAMSHAW 1. REASON FOR COMMITTEE CONSIDERATION Contrary to Parish Council view 2. DEVELOPMENT PLAN DESIGNATION Conservation Area: Fritham 3. PRINCIPAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN POLICIES DP1 General Development Principles DP6 Design Principles DP11 Extensions to Dwellings CP7 The Built Environment CP8 Local Distinctiveness 4. SUPPLEMENTARY PLANNING GUIDANCE Design Guide SPD 5. NATIONAL PLANNING POLICY FRAMEWORK Sec 7 - Requiring good design Sec 11 - Conserving and enhancing the natural environment Sec 12 - Conserving and enhancing the historic environment 6. MEMBER COMMENTS Edward Heron: The proposed extensions are wholly in keeping with the area, offer a significant improvement on the existing and due to their mass and form are clearly subservient to the existing building. 7. PARISH COUNCIL COMMENTS 1 Bramshaw Parish Council: Recommend permission: • Removes a flat roof extension which isn't in keeping with the property or the conservation area. • It is an improvement on what is already there with the resultant changes being minor to the visual amenity of the local area, particularly as the work is to the rear of the property and does not alter the appearance of the front of the property. • The house will become a more complete dwelling for the current occupier by providing a house suitable for modern living (particularly with the provision of a downstairs WC). • The two storey extension will, because of its reduced height be subservient to the original property. -

CIN Silent Auction Email-1

SALTERNS SAILING CLUB SILENT AUCTION RULES • Bidding increments up to £100 - £5 increment • Bidding increments over £100 - £10 increment • Meryl Armitage will be monitoring the Silent Auction and will be closing the auction at 4.00pm on Saturday 15th November 2014 and her decision on all bids will be final. Meryl’s Mobile 07966103119 • Telephone/Absent bidding is welcome via your own appointed nominee • All new bids must be higher than the previous bid by at least the minimum raise indicated above, in order to be valid. • A bid is construed as a legal agreement to purchase the listed item(s) at the amount indicated. All bidders must be 18 years of age or above. • All winning bids must be settled within two weeks or the item will go to the next highest bidder. • In order to protect the integrity of all bidders, please do not scratch out bids. Bids may only be voided by Meryl due to valid bidding error. Please seek assistance if you find an invalid bid or make a mistake during bidding. The auction will close at 4.00pm On Saturday 15th November 2014, at which time the highest bid on each bid sheet will be declared the winner. If conflict arises over identifying the last valid bid for an item(s), Meryl has the sole discretion to determine the winner. 1. Luxury Villa In Antigua Kindly donated by Rupert and Victoria Miles • A holiday Apartment in the renowned Caribbean sailing resort of Nonsuchbay in Antigua (nonsuchbayresort.com) • Sleeps 4 in a 5 star 2 bed, 2 bathroom apartment, overlooking the beach, with twice weekly maid service. -

Hordle Lakes

HORDLE LAKES HORDLE, HAMPSHIRE A Highly Regarded Coarse Fishery Providing An Excellent Lifestyle & Business Opportunity With Further Potential, Situated In A Most Desirable Rural Location The lakes are heavily stocked with Carp, Tench, Perch, Bream, Roach, SITUATION Chubb & Rudd providing excellent sport which has enabled the LAKES fishery to become recognised nationally achieving regular coverage New Milton 1.3 miles, Lymington 5 miles, Brockenhurst 6.2 miles, Spring Lake Extending to 0.7 acres, Spring lake provides 20 pegs across various angling publications. Anglers Mail voted the site as Christchurch 8.8 miles, Cadnam (M27) 15.5 miles, Bourne- and holds Carp up to 24lbs along with Tench to 7lbs, Bream to one of the top 100 British Commercial Fisheries in 2010. mouth 15 miles 6lbs, Perch to 3lbs and Roach and Rudd. A number of islands offer Railway Stations: Brockenhurst to London/Waterloo 1h 36mins, good features with lily pads and rushes. New Milton to London/Waterloo 1h 44mins The spring fed lakes cater for day ticket anglers, fishing clubs who International Airports: Bournemouth International Airport hold regular matches and specimen anglers who can night fish 10 miles. Southampton 25 miles. subject to booking. Many of the lakes also enjoy easy disabled access from the carpark. Hordle Lakes is situated in the popular village of Hordle on the southern edge of The New Forest National Park and enjoys an The current owners supplement their income with tuition; tackle sales attractive rural setting with easy access from Ashley Road. The property and refreshments with scope to develop the business and property benefits from good communication links with the A31 & A35 to the further, subject to obtaining the necessary planning consents. -

Eling to Holbury Cycle Route Improvements Transforming Cities Fund Eling to Holbury Cycle Route Improvements 2

1.Welcome Eling to Holbury Cycle Route Improvements Transforming Cities Fund Eling to Holbury Cycle Route Improvements 2. Content Scheme Overview What we Funding will cover today Scheme Plans Q&A Eling to Holbury Cycle Route Improvements 3. Scheme Overview and Aims Scheme overview & Aims This scheme proposes to enhance cycle connectivity between Southampton, Totton, Marchwood, Hythe and Holbury as well as connecting to the existing Southampton City Council's Cycle Network SCN Route 1 and the National Cycling Network. This scheme will utilise and join up existing cycle routes together with providing new routes by improving crossing facilities and providing signage. The key aims of the scheme are: ✓ To encourage people to cycle locally to access facilities and services in the Waterside area. ✓ Better connectivity between the settlements by ensuring that existing cycling provisions are enhanced and connected. ✓ To improve footways, footpaths, and existing cycle routes to ensure they are clearly signed and marked. ✓ To improve cycle connectivity in the area and encouraging people to either or walk or cycle as their first choice of local travel by providing a better connected, safe, and serviceable network for the people in the area, supporting economic growth and helping to improve the local and regional economy. Funding In March 2020, Hampshire County Council welcomed news of the successful outcome of funding bids to the Department for Transport (DfT). Made jointly with Southampton City Council, Hampshire County Council made a bid for investment designed to improve walking, cycling and public transport within the Southampton City Region. The Department for Transport awarded £57 million to the Southampton City Region from the Transforming Cities Fund (TCF). -

Excavation of Three Romano-British Pottery Kilns in Amberwood Inglosure, Near Fritham, New Forest

EXCAVATION OF THREE ROMANO-BRITISH POTTERY KILNS IN AMBERWOOD INGLOSURE, NEAR FRITHAM, NEW FOREST By M. G. FULFORD INTRODUCTION THE three kilns were situated on the slopes of a slight, marshy valley (now marked by a modern Forestry Commission drain) which runs south through the Amberwood Inclosure to the Latchmore Brook (fig. i). The subsoil consists of the clay and sandy gravel deposits of the Bracklesham beds. Kilns i (SU 20541369) and 2 are at the head of this shallow valley at about 275 feet O.D. on a south-east facing slope, Fig. 1. Location maps to show the Amberwood and other Romano-British kilns in the New Forest. 5 PROCEEDINGS FOR THE YEAR 1971 while kiln 3 (at SU 20631360) is some 100 metres to the south on the eastern side of the valley at 250 feet O.D. Previous work in the New Forest does not record any kiln in the Amberwood Inclosure. A hoard of coins was found (Akerman, 1853) in this area, but only two of the coins are recorded; one of Julian (355-363) and one of Valens (364-78). Sumner (1927) records finding a quern-stone and pottery at about SU 20701383, and Pasmore (1967) lists a series of possible sites within the Inclosure. Other find spots on the map in Sumner (1927, facing p. 85) suggest he may have been the first to find the waste heaps of kiln 1, but kiln 3 was only traced by Mr. A. Pasmore after the withdrawal of timber following the felling of hardwood in 1969-70. -

Current Live Appeals (Planning and Enforcement) 2017 - 2018

Current Live Appeals (Planning and Enforcement) 2017 - 2018 Date Case Address Procedure Current Status Received Reference 08/09/2017 ENF Ria House Written Awaiting Decision 17/0073 Ringwood Road Representations Woodlands SO40 7GX 23/10/2017 ENF Meadow View Written Awaiting Decision 17/0121 Cottage Representations (Formerly Torbay) Pound Lane Burley BH24 4ED 27/10/2017 ENF 2 Tanners Lane Inquiry (3 Days) Inquiry Dates 17/0083 East End Lymington All appeals at this site 04 – 06 September Notice 1 SO41 5SP linked 2018 27/10/2017 ENF 2 Tanners Lane Inquiry (3 Days) Inquiry Dates 17/0083 East End Lymington All appeals at this site 04 – 06 September Notice 1 SO41 5SP linked 2018 27/10/2017 ENF 2 Tanners Lane Inquiry (3 Days) Inquiry Dates 17/0083 East End Lymington All appeals at this site 04 – 06 September Notice 2 SO41 5SP linked 2018 27/10/2017 ENF 2 Tanners Lane Inquiry (3 Days) Inquiry Dates 17/0083 East End Lymington All appeals at this site 04 – 06 September Notice 2 SO41 5SP linked 2018 05/12/2017 17/00451 Fritillaries Hearing Hearing Date: Brockhill Nursery 25 July 2018 Sway Road Lymington SO41 6FR 14/12/2017 17/00710 The Beeches Hearing Statement Due: Romsey Road 20 July 2018 Ower (Linked with ENF Romsey 17/0114) Hearing Date: SO51 6AF To be confirmed Date Case Address Procedure Current Status Received Reference 14/12/2017 ENF The Beeches Hearing Statement Due: 17/0114 Romsey Road 20 July 2018 Ower (Linked with 17/00710) Romsey Hearing Date; SO51 6AF To be confirmed 19/12/2017 17/00816 The Lodge Written Representation Awaiting Decision -

Local Produce Guide

FREE GUIDE AND MAP 2019 Local Produce Guide Celebrating 15 years of helping you to find, buy and enjoy top local produce and craft. Introducing the New Forest’s own registered tartan! The Sign of True Local Produce newforestmarque.co.uk Hampshire Fare ‘‘DON’T MISS THIS inspiring a love of local for 28 years FABULOUS SHOW’’ MW, Chandlers Ford. THREE 30th, 31st July & 1st DAYS ONLY August 2019 ''SOMETHING FOR THE ''MEMBERS AREA IS WHOLE FAMILY'' A JOY TO BE IN'' PA, Christchurch AB, Winchester Keep up to date and hear all about the latest foodie news, events and competitions Book your tickets now and see what you've been missing across the whole of the county. www.hampshirefare.co.uk newforestshow.co.uk welcome! ? from the New Forest Marque team Thank you for supporting ‘The Sign of True Local Produce’ – and picking up your copy of the 2019 New Forest Marque Local Produce Guide. This year sees us celebrate our 15th anniversary, a great achievement for all involved since 2004. Originally formed as ‘Forest Friendly Farming’ the New Forest Marque was created to support Commoners and New Forest smallholders. Over the last 15 years we have evolved to become a wide reaching ? organisation. We are now incredibly proud to represent three distinct areas of New Forest business; Food and Drink, Hospitality and Retail and Craft, Art, Trees and Education. All are inherently intertwined in supporting our beautiful forest ecosystem, preserving rural skills and traditions and vital to the maintenance of a vibrant rural economy. Our members include farmers, growers and producers whose food and drink is grown, reared or caught in the New Forest or brewed and baked using locally sourced ingredients. -

Section 3: Site-Specific Proposals – Totton and the Waterside

New Forest District (outside the National Park) Local Plan Part 2: Sites and Development Management Adopted April 2014 Section 3: Site-specific Proposals – Totton and the Waterside 57 New Forest District (outside the National Park) Local Plan Part 2: Sites and Development Management Adopted April 2014 58 New Forest District (outside the National Park) Local Plan Part 2: Sites and Development Management Adopted April 2014 3.1 The site-specific policies in this section are set out settlement by settlement – broadly following the structure of Section 9 of the Core Strategy: Local implications of the Spatial Strategy. 3.2 The general policies set out in: • the Core Strategy, • National Planning Policy and • Development Management policies set out in Section 2 of this document; all apply where relevant. 3.3 Supplementary Planning Documents (SPDs) will be prepared where appropriate to provide detailed guidance on particular policies and proposals. In particular, Development Briefs will be prepared to provide detailed guidance on the implementation of the main site allocations. Improving access to the Waterside 3.4 The Transport section (7.9) of the Core Strategy notes that access to Totton and the Waterside is “not so good”, particularly as the A326 is often congested. Core Strategy Policy CS23 states support for improvements that reduce congestion, improve accessibility and improve road safety. Core Strategy Policy CS23 also details some specific transport proposals in Totton and the Waterside that can help achieve this. The transport schemes detailed below are those that are not specific to a particular settlement within the Totton and Waterside area, but have wider implications for this area as a whole. -

Group Booking Form 2017

GroupGroup Booking Booking Information Form 20172018 Stunning spring Herbaceous displays of borders of exotic rhododendrons, summer colour azaleas and Autumn splendour camellias and fabulous fungi Exhibitions We politely ask that final numbers Our website is regularly updated with are confirmed to us 48 hours before details of forthcoming exhibitions held arrival date. in the Five Arrows Gallery, set within Pre-payment – Cheques should be our Gardens. made payable to Exbury Gardens How to Get to Exbury Ltd. Payment can be made by credit 20 minutes south of junction 2, M27 card by phoning the Group Bookings West. Take the A326 and follow the Administrator on 02380 891203. brown tourist signs to Exbury Gardens Payment on arrival – If payment is to & Steam Railway. Approximate be made on arrival, the Group Organiser driving times: Southampton – 30 or Coach Driver should approach our minutes, Bournemouth – 60 minutes, designated group entrance and pay for Oxford – 1 hour 30 minutes, all the gardens admissions. Pre-booked London – 2 hours. Steam Railway tickets will be available for collection at this point. Payment – Payment for group visits Date Exclusions – (only railway) - can be made in advance or on arrival. Groups cannot be booked during our Halloween event. Group Organiser receives free entry into the Gardens and a free ride on the Exbury Steam Railway. Coach drivers are entitled to free entry into the Gardens, a train ride and a discount in Mr Eddy’s Tea Rooms. How to find us Exbury’s beautiful woodland garden covers 200 acres and is a jewel in the Exbury Gardens, SO45 1AZ.