Hendrick S. Wright and the "Nocturnal Committee"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Martin Van Buren: the Greatest American President

SUBSCRIBE NOW AND RECEIVE CRISIS AND LEVIATHAN* FREE! “The Independent Review does not accept “The Independent Review is pronouncements of government officials nor the excellent.” conventional wisdom at face value.” —GARY BECKER, Noble Laureate —JOHN R. MACARTHUR, Publisher, Harper’s in Economic Sciences Subscribe to The Independent Review and receive a free book of your choice* such as the 25th Anniversary Edition of Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American Government, by Founding Editor Robert Higgs. This quarterly journal, guided by co-editors Christopher J. Coyne, and Michael C. Munger, and Robert M. Whaples offers leading-edge insights on today’s most critical issues in economics, healthcare, education, law, history, political science, philosophy, and sociology. Thought-provoking and educational, The Independent Review is blazing the way toward informed debate! Student? Educator? Journalist? Business or civic leader? Engaged citizen? This journal is for YOU! *Order today for more FREE book options Perfect for students or anyone on the go! The Independent Review is available on mobile devices or tablets: iOS devices, Amazon Kindle Fire, or Android through Magzter. INDEPENDENT INSTITUTE, 100 SWAN WAY, OAKLAND, CA 94621 • 800-927-8733 • [email protected] PROMO CODE IRA1703 Martin Van Buren The Greatest American President —————— ✦ —————— JEFFREY ROGERS HUMMEL resident Martin Van Buren does not usually receive high marks from histori- ans. Born of humble Dutch ancestry in December 1782 in the small, upstate PNew York village of Kinderhook, Van Buren gained admittance to the bar in 1803 without benefit of higher education. Building on a successful country legal practice, he became one of the Empire State’s most influential and prominent politi- cians while the state was surging ahead as the country’s wealthiest and most populous. -

Rush Family Papers Rush Finding Aid Prepared by Finding Aid Prepared by Holly Mengel

Rush family papers Rush Finding aid prepared by Finding aid prepared by Holly Mengel. Last updated on September 02, 2020. Library Company of Philadelphia Rush family papers Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 7 Administrative Information......................................................................................................................... 14 Related Materials......................................................................................................................................... 15 Controlled Access Headings........................................................................................................................15 Other Finding Aids note..............................................................................................................................17 Collection Inventory.................................................................................................................................... 18 Series I. Benjamin Rush papers........................................................................................................... -

1835. EXECUTIVE. *L POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT

1835. EXECUTIVE. *l POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT. Persons employed in the General Post Office, with the annual compensation of each. Where Compen Names. Offices. Born. sation. Dol. cts. Amos Kendall..., Postmaster General.... Mass. 6000 00 Charles K. Gardner Ass't P. M. Gen. 1st Div. N. Jersey250 0 00 SelahR. Hobbie.. Ass't P. M. Gen. 2d Div. N. York. 2500 00 P. S. Loughborough Chief Clerk Kentucky 1700 00 Robert Johnson. ., Accountant, 3d Division Penn 1400 00 CLERKS. Thomas B. Dyer... Principal Book Keeper Maryland 1400 00 Joseph W. Hand... Solicitor Conn 1400 00 John Suter Principal Pay Clerk. Maryland 1400 00 John McLeod Register's Office Scotland. 1200 00 William G. Eliot.. .Chie f Examiner Mass 1200 00 Michael T. Simpson Sup't Dead Letter OfficePen n 1200 00 David Saunders Chief Register Virginia.. 1200 00 Arthur Nelson Principal Clerk, N. Div.Marylan d 1200 00 Richard Dement Second Book Keeper.. do.. 1200 00 Josiah F.Caldwell.. Register's Office N. Jersey 1200 00 George L. Douglass Principal Clerk, S. Div.Kentucky -1200 00 Nicholas Tastet Bank Accountant Spain. 1200 00 Thomas Arbuckle.. Register's Office Ireland 1100 00 Samuel Fitzhugh.., do Maryland 1000 00 Wm. C,Lipscomb. do : for) Virginia. 1000 00 Thos. B. Addison. f Record Clerk con-> Maryland 1000 00 < routes and v....) Matthias Ross f. tracts, N. Div, N. Jersey1000 00 David Koones Dead Letter Office Maryland 1000 00 Presley Simpson... Examiner's Office Virginia- 1000 00 Grafton D. Hanson. Solicitor's Office.. Maryland 1000 00 Walter D. Addison. Recorder, Div. of Acc'ts do.. -

James Knox Polk Collection, 1815-1949

State of Tennessee Department of State Tennessee State Library and Archives 403 Seventh Avenue North Nashville, Tennessee 37243-0312 POLK, JAMES KNOX (1795-1849) COLLECTION 1815-1949 Processed by: Harriet Chapell Owsley Archival Technical Services Accession Numbers: 12, 146, 527, 664, 966, 1112, 1113, 1140 Date Completed: April 21, 1964 Location: I-B-1, 6, 7 Microfilm Accession Number: 754 MICROFILMED INTRODUCTION This collection of James Knox Polk (1795-1849) papers, member of Tennessee Senate, 1821-1823; member of Tennessee House of Representatives, 1823-1825; member of Congress, 1825-1839; Governor of Tennessee, 1839-1841; President of United States, 1844-1849, were obtained for the Manuscripts Section by Mr. and Mrs. John Trotwood Moore. Two items were given by Mr. Gilbert Govan, Chattanooga, Tennessee, and nine letters were transferred from the Governor’s Papers. The materials in this collection measure .42 cubic feet and consist of approximately 125 items. There are no restrictions on the materials. Single photocopies of unpublished writings in the James Knox Polk Papers may be made for purposes of scholarly research. SCOPE AND CONTENT The James Knox Polk Collection, composed of approximately 125 items and two volumes for the years 1832-1848, consist of correspondence, newspaper clippings, sketches, letter book indexes and a few miscellaneous items. Correspondence includes letters by James K. Polk to Dr. Isaac Thomas, March 14, 1832, to General William Moore, September 24, 1841, and typescripts of ten letters to Major John P. Heiss, 1844; letters by Sarah Polk, 1832 and 1891; Joanna Rucker, 1845- 1847; H. Biles to James K. Polk, 1833; William H. -

Xerox University Microfilms 3 0 0North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 75 - 21,515

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1 .T h e sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper le ft hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

A History of Maryland's Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016

A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 Published by: Maryland State Board of Elections Linda H. Lamone, Administrator Project Coordinator: Jared DeMarinis, Director Division of Candidacy and Campaign Finance Published: October 2016 Table of Contents Preface 5 The Electoral College – Introduction 7 Meeting of February 4, 1789 19 Meeting of December 5, 1792 22 Meeting of December 7, 1796 24 Meeting of December 3, 1800 27 Meeting of December 5, 1804 30 Meeting of December 7, 1808 31 Meeting of December 2, 1812 33 Meeting of December 4, 1816 35 Meeting of December 6, 1820 36 Meeting of December 1, 1824 39 Meeting of December 3, 1828 41 Meeting of December 5, 1832 43 Meeting of December 7, 1836 46 Meeting of December 2, 1840 49 Meeting of December 4, 1844 52 Meeting of December 6, 1848 53 Meeting of December 1, 1852 55 Meeting of December 3, 1856 57 Meeting of December 5, 1860 60 Meeting of December 7, 1864 62 Meeting of December 2, 1868 65 Meeting of December 4, 1872 66 Meeting of December 6, 1876 68 Meeting of December 1, 1880 70 Meeting of December 3, 1884 71 Page | 2 Meeting of January 14, 1889 74 Meeting of January 9, 1893 75 Meeting of January 11, 1897 77 Meeting of January 14, 1901 79 Meeting of January 9, 1905 80 Meeting of January 11, 1909 83 Meeting of January 13, 1913 85 Meeting of January 8, 1917 87 Meeting of January 10, 1921 88 Meeting of January 12, 1925 90 Meeting of January 2, 1929 91 Meeting of January 4, 1933 93 Meeting of December 14, 1936 -

ELECTORAL VOTES for PRESIDENT and VICE PRESIDENT Ø902¿ 69 77 50 69 34 132 132 Total Total 21 10 21 10 21 Va

¿901¿ ELECTORAL VOTES FOR PRESIDENT AND VICE PRESIDENT ELECTORAL VOTES FOR PRESIDENT AND VICE PRESIDENT 901 ELECTION FOR THE FIRST TERM, 1789±1793 GEORGE WASHINGTON, President; JOHN ADAMS, Vice President Name of candidate Conn. Del. Ga. Md. Mass. N.H. N.J. Pa. S.C. Va. Total George Washington, Esq ................................................................................................... 7 3 5 6 10 5 6 10 7 10 69 John Adams, Esq ............................................................................................................... 5 ............ ............ ............ 10 5 1 8 ............ 5 34 Samuel Huntington, Esq ................................................................................................... 2 ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ 2 1027 John Jay, Esq ..................................................................................................................... ............ 3 ............ ............ ............ ............ 5 ............ ............ 1 9 John Hancock, Esq ............................................................................................................ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ 2 1 1 4 Robert H. Harrison, Esq ................................................................................................... ............ ............ ............ 6 ............ ............ ............ ............ ............ ........... -

Life of General Lewis Cass

Class E-'MO i^i4 / GENERAL CASS. LIFE OF GENERAL LEWIS CASS: COMPRISING AN ACCOUNT OF HIS MILITARY SERVICES IN THE NORTH-WEST DURING THE WAR WITH GREAT BRITAIN, HIS DIPLOMATIC CAREER AND CIVIL HISTORY. TO WHICH IS APPENDED A SKETCH OF THE PUBLIC AND PRIVATE HISTORY OF MAJOR-GENERAL W. 0. BUTLER, OF THE VOLUNTEER SERVICE OF THE UNITED STATES. WITH TWO PORTRAITS, PHILADELPHIA: G. B. Z I E B E R & CO 1848. Entered, according to the Act of Congress, in the year 1848, by G. B. ZIEBER &. CO. in the clerk's office of the District Court of the United States for * the Eastern District of Pennsylvania. STEREOTYPED BY J. FAG AN PRINTED BY C SHERMAN. (2) PREFACE. The following pages profess to be nothing more than a compilation thrown together within a brief space of time, to illustrate the career of the distinguished men nominated as candidates for the two first offices of the na- tion. Without aspirations after literary merit, it has been sought to give a popular account of the eventful lives of these personages, and to place them in a proper position before the people, without dwelling too long on the in- tricacies of politics and party. When these became the subject, General Cass has been caused, as far as possible, to speak for himself, (iii) iv PREFACE. and extracts from his many printed speeches and essays have been made, to which the reader will not object, it* he has a perception of power and eloquence. In the account of General Butler, little more has been done than to expand the well- written sketch of Mr. -

![CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8733/chairmen-of-senate-standing-committees-table-5-3-1789-present-978733.webp)

CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present

CHAIRMEN OF SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–present INTRODUCTION The following is a list of chairmen of all standing Senate committees, as well as the chairmen of select and joint committees that were precursors to Senate committees. (Other special and select committees of the twentieth century appear in Table 5-4.) Current standing committees are highlighted in yellow. The names of chairmen were taken from the Congressional Directory from 1816–1991. Four standing committees were founded before 1816. They were the Joint Committee on ENROLLED BILLS (established 1789), the joint Committee on the LIBRARY (established 1806), the Committee to AUDIT AND CONTROL THE CONTINGENT EXPENSES OF THE SENATE (established 1807), and the Committee on ENGROSSED BILLS (established 1810). The names of the chairmen of these committees for the years before 1816 were taken from the Annals of Congress. This list also enumerates the dates of establishment and termination of each committee. These dates were taken from Walter Stubbs, Congressional Committees, 1789–1982: A Checklist (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985). There were eleven committees for which the dates of existence listed in Congressional Committees, 1789–1982 did not match the dates the committees were listed in the Congressional Directory. The committees are: ENGROSSED BILLS, ENROLLED BILLS, EXAMINE THE SEVERAL BRANCHES OF THE CIVIL SERVICE, Joint Committee on the LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LIBRARY, PENSIONS, PUBLIC BUILDINGS AND GROUNDS, RETRENCHMENT, REVOLUTIONARY CLAIMS, ROADS AND CANALS, and the Select Committee to Revise the RULES of the Senate. For these committees, the dates are listed according to Congressional Committees, 1789– 1982, with a note next to the dates detailing the discrepancy. -

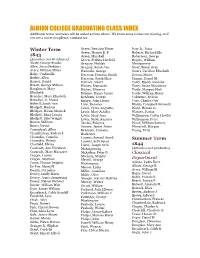

ALBION COLLEGE GRADUATING CLASS INDEX Additional Terms and Years Will Be Added As Time Allows

ALBION COLLEGE GRADUATING CLASS INDEX Additional terms and years will be added as time allows. We know some names are missing, so if you see a correction please, contact us. Winter Term Green, Denslow Elmer Pray Jr., Isaac Green, Harriet E. F. Roberts, Richard Ely 1843 Green, Marshall Robertson, George [Attendees not Graduates] Green, Perkins Hatfield Rogers, William Alcott, George Brooks Gregory, Huldah Montgomery Allen, Amos Stebbins Gregory, Sarah Ann Stout, Byron Gray Avery, William Miller Hannahs, George Stuart, Caroline Elizabeth Baley, Cinderella Harroun, Denison Smith Sutton, Moses Barker, Ellen Harroun, Sarah Eliza Timms, Daniel M. Barney, Daniel Herrick, Albert Torry, Ripley Alcander Basset, George Stillson Hickey, Manasseh Torry, Susan Woodbury Baughman, Mary Hickey, Minerva Tuttle, Marquis Hull Elizabeth Holmes, Henry James Tuttle, William Henry Benedict, Mary Elizabeth Ketchum, George Volentine, Nelson Benedict, Jr, Moses Knapp, John Henry Vose, Charles Otis Bidwell, Sarah Ann Lake, Dessoles Waldo, Campbell Griswold Blodgett, Hudson Lewis, Cyrus Augustus Ward, Heman G. Blodgett, Hiram Merrick Lewis, Mary Athalia Warner, Darius Blodgett, Mary Louisa Lewis, Mary Jane Williamson, Calvin Hawley Blodgett, Silas Wright Lewis, Sarah Augusta Williamson, Peter Brown, William Jacobs, Rebecca Wood, William Somers Burns, David Joomis, James Joline Woodruff, Morgan Carmichael, Allen Ketchum, Cornelia Young, Urial Chamberlain, Roderick Rochester Champlin, Cornelia Loomis, Samuel Sured Summer Term Champlin, Nelson Loomis, Seth Sured Chatfield, Elvina Lucas, Joseph Orin 1844 Coonradt, Ann Elizabeth Mahaigeosing [Attendees not graduates] Coonradt, Mary Margaret McArthur, Peter D. Classical Cragan, Louisa Mechem, Stanley Cragan, Matthew Merrill, George Department Crane, Horace Delphin Washington Adkins, Lydia Flora De Puy, Maria H. Messer, Lydia Allcott, George B. -

INTRODUCTION T the Time of His Death, in April I8I3, Benjamin Rush Was a at the Zenith of His Fame and Influence

INTRODUCTION T the time of his death, in April I8I3, Benjamin Rush was A at the zenith of his fame and influence. Long regarded by everyone except himself and perhaps a few other Philadelphians as the leading citizen of Philadelphia, the recipient of uncounted honors from his countrymen and from European courts and learned societies, Rush had achieved a reputation not surpassed by that of any other American physician for a century or more to come. If eulogists are to be distrusted, we have the testimony of a pupil, who was himself to become a great physician, writing a few months before his teacher died. In January I8IJ Charles D. Meigs re ported to his father in Georgia: "Dr. Rush looks like an angel of light, his words bear in them, and his looks too, irresistable per suasion and conviction :-in fact, to me he seems more than mortal. If ever a human being deserved Deification, it is Dr. Rush.m Rush's fame sprang from his own vigorous and magnetic person ality; from his substantial accomplishments in medicine, psychiatry, education, and social reform; from the great body of his published writings; from his gifts as a teacher and lecturer; and, finally, from the letters he wrote to scores of friends, relatives, patients, pupils, and colleagues on both sides of the Atlantic. In I 8 I 6 a former puyil, Dr. James Mease of Philadelphia, was happily inspired to gather and publish cca volume or more of the letters of my late friend Dr Rush to various persons on political, religious, and mis cellaneous subjects." For this purpose Mease solicited the aid of two of Rush's intimate correspondents, ex-Presidents Adams and Jefferson. -

SILAS WRIGHT AMD TEE ANTI-RENT WAR, 18¥F-18^6

SILAS WRIGHT AMD TEE ANTI-RENT WAR, 18¥f-18^6 APPROVED: Ail Mayor Professor Minor Professor "1 director of the Department of History ,7 -7 ~_i_ ^ / lean'of the Graduate School" SILAS WEIGHT AND THE ANT I-BENT WAR, 18HV-18^-6 THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Eldrldge PL Pendleton, B. A. Denton. Texas January, 1968 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS ii Chapter I. THE NEW YORK LEASEHOLD SYSTEM AND THE ANTI-RENT REBELLION 1 II. SILAS WRIGHT - RELUCTANT CANDIDATE 28 III. "MAKE NO COMPROMISES WITH ANY ISMS." 59 IV. THE FALL OF KING SILAS ............ 89 APPENDIX ... 128 BIBLIOGRAPHY 133 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Leasehold Counties in New York 18V+-18V6 132 ii CHAPTER I THE NEW YORK LEASEHOLD SYSTEM AND THE ANTI-RENT REBELLION Silas Wright was one of the most universally respected Democrats of the Jacksonian period. As United States Senator from 1833 to 18M+, he established a record for political integrity, honesty, and courage that made him a valuable leader of the Democratic Party and gained for him the respect of the Whig opposition. Wright's position in Washington as a presidential liaison in the Senate caused him to play an influential role in both the Jackson and Van Bur9:1 administrations. He maintained a highly developed sense of political Idealism throughout his career. Although Wright was aware of the snares of political corruption that continually beset national politicians, his record remained irreproachable and untainted.^ The conditions of political life during the Jacksonian era were an affront to Wright's sense of idealism- Gradually disillusioned by the political .