Securing Protected Area Integrity and Rural People's Livelihoods: Lessons for Twelve Years of the Kibale and Semliki Conservation and Development Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

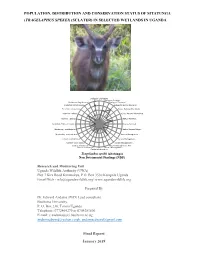

Population, Distribution and Conservation Status of Sitatunga (Tragelaphus Spekei) (Sclater) in Selected Wetlands in Uganda

POPULATION, DISTRIBUTION AND CONSERVATION STATUS OF SITATUNGA (TRAGELAPHUS SPEKEI) (SCLATER) IN SELECTED WETLANDS IN UGANDA Biological -Life history Biological -Ecologicl… Protection -Regulation of… 5 Biological -Dispersal Protection -Effectiveness… 4 Biological -Human tolerance Protection -proportion… 3 Status -National Distribtuion Incentive - habitat… 2 Status -National Abundance Incentive - species… 1 Status -National… Incentive - Effect of harvest 0 Status -National… Monitoring - confidence in… Status -National Major… Monitoring - methods used… Harvest Management -… Control -Confidence in… Harvest Management -… Control - Open access… Harvest Management -… Control of Harvest-in… Harvest Management -Aim… Control of Harvest-in… Harvest Management -… Control of Harvest-in… Tragelaphus spekii (sitatunga) NonSubmitted Detrimental to Findings (NDF) Research and Monitoring Unit Uganda Wildlife Authority (UWA) Plot 7 Kira Road Kamwokya, P.O. Box 3530 Kampala Uganda Email/Web - [email protected]/ www.ugandawildlife.org Prepared By Dr. Edward Andama (PhD) Lead consultant Busitema University, P. O. Box 236, Tororo Uganda Telephone: 0772464279 or 0704281806 E-mail: [email protected] [email protected], [email protected] Final Report i January 2019 Contents ACRONYMS, ABBREVIATIONS, AND GLOSSARY .......................................................... vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................... viii 1.1Background ........................................................................................................................... -

Kamwenge District Local Government

KAMWENGE DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT FIVE-YEAR DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2015/2016 – 2019/2020 Vision The vision of Kamwenge District is ‚Improved quality of life for all the people of Kamwenge by the year 2030‛. Theme Sustainable wealth creation through infrastructure development, food security and environment conservation for a healthy and productive population” Approved by the District Council under Minute 46/COU/2014/2015 REVISED EDITION 2016 i LIST OF ACRONYMS ACODEV Action for Community Development ADRA Adventist Relief Agency ARVs Anti Retroviral drugs BFP Budget Framework Programme BMUs Beach Management Units CAO Chief Administrative Officer CBO Community Based Organisation CBS Community Based Services CDD Community Driven Development CDO Community Development Officer CFO Chief Finance Officer CNDPF Comprehensive National Development Planning Framework CORPs Community Own Resource Persons CSO Civil Society Organisation DDP District Development plan DHO District Health Officer DISO District Internal Security Officer DLSP District Livelihoods Support Programme DNRO District Natural Resources Office DWSCC District Water and Sanitation Coordination Committee FAL Functional Adult Literacy GFS Gravity Flow Scheme HEWASA Health through Water and Sanitation HLG Higher Local Government HMIS Health Management Information System HSD Health Sub District IGAs Income Generating Activities IMCI Integrated Management of Child Illness JESE Joint Effort to Save the Environment KABECOS Kamwenge Bee keepers Association KRC Kabarole Research and Resource Centre -

UGANDA: PLANNING MAP (Details)

IMU, UNOCHA Uganda http://www.ugandaclusters.ug http://ochaonline.un.org UGANDA: PLANNING MAP (Details) SUDAN NARENGEPAK KARENGA KATHILE KIDEPO NP !( NGACINO !( LOPULINGI KATHILE AGORO AGU FR PABAR AGORO !( !( KAMION !( Apoka TULIA PAMUJO !( KAWALAKOL RANGELAND ! KEI FR DIBOLYEC !( KERWA !( RUDI LOKWAKARAMOE !( POTIKA !( !( PAWACH METU LELAPWOT LAWIYE West PAWOR KALAPATA MIDIGO NYAPEA FR LOKORI KAABONG Moyo KAPALATA LODIKO ELENDEREA PAJAKIRI (! KAPEDO Dodoth !( PAMERI LAMWO FR LOTIM MOYO TC LICWAR KAPEDO (! WANDI EBWEA VUURA !( CHAKULYA KEI ! !( !( !( !( PARACELE !( KAMACHARIKOL INGILE Moyo AYUU POBURA NARIAMAOI !( !( LOKUNG Madi RANGELAND LEFORI ALALI OKUTI LOYORO AYIPE ORAA PAWAJA Opei MADI NAPORE MORUKORI GWERE MOYO PAMOYI PARAPONO ! MOROTO Nimule OPEI PALAJA !( ALURU ! !( LOKERUI PAMODO MIGO PAKALABULE KULUBA YUMBE PANGIRA LOKOLIA !( !( PANYANGA ELEGU PADWAT PALUGA !( !( KARENGA !( KOCHI LAMA KAL LOKIAL KAABONG TEUSO Laropi !( !( LIMIDIA POBEL LOPEDO DUFILE !( !( PALOGA LOMERIS/KABONG KOBOKO MASALOA LAROPI ! OLEBE MOCHA KATUM LOSONGOLO AWOBA !( !( !( DUFILE !( ORABA LIRI PALABEK KITENY SANGAR MONODU LUDARA OMBACHI LAROPI ELEGU OKOL !( (! !( !( !( KAL AKURUMOU KOMURIA MOYO LAROPI OMI Lamwo !( KULUBA Koboko PODO LIRI KAL PALORINYA DUFILE (! PADIBE Kaabong LOBONGIA !( LUDARA !( !( PANYANGA !( !( NYOKE ABAKADYAK BUNGU !( OROM KAABONG! TC !( GIMERE LAROPI PADWAT EAST !( KERILA BIAFRA !( LONGIRA PENA MINIKI Aringa!( ROMOGI PALORINYA JIHWA !( LAMWO KULUYE KATATWO !( PIRE BAMURE ORINJI (! BARINGA PALABEK WANGTIT OKOL KINGABA !( LEGU MINIKI -

Two Rwandese Nationals Sentenced to 12 Years in Jail for Poaching | Chimpreports

5.7.2021 Two Rwandese Nationals Sentenced to 12 Years in Jail for Poaching | ChimpReports News Two Rwandese Nationals Sentenced to 12 Years in Jail for Poaching Arafat Nzito • July 4, 2021 1 minute read Two Rwandese nationals identified as Habimana Sabanitah and Sobomana Augustine have been sentenced to 12 years in jail for illegal entry and killing of protected wildlife species. The two, both residents of Rwamwanja refugee settlement in Kamwenge district, were found in possession of a dead bush buck inside Katonga Wildlife Reserve. LUISA CERANO - Long-Cardigan aus Mohair-Mix - 34 - braun - Damen Luisa Cerano | Sponsored By using this website, you agree that we and our partners may set cookies for purposes such as customisingRead Next Scontenttory and advertising.TranslateI Understand » https://chimpreports.com/two-rwandese-nationals-sentenced-to-12-years-in-jail-for-poaching/ 1/7 5.7.2021 Two Rwandese Nationals Sentenced to 12 Years in Jail for Poaching | ChimpReports According to the Uganda Wildlife Authority (UWA), the two were arrested on June 28, 2021 by UWA personnel inside Katonga Wildlife Reserve. “They were found in possession of a dead bush buck, 2 pangas, 2 sharp spears and 8 wire snares that were used to kill the animal,” UWA stated. Upon arrest, the suspects were transferred to Kyegegwa police station and later produced before the Chief Magistrate’s Court of Kyenjojo to take plea. The accused pleaded guilty to the counts as charged of illegal entry and killing a protected wildlife species. Prosecution led by Latif Amis argued that the two deprived the wider public and national economy the benefits of conservation including tourism, employment and foreign exchange earnings. -

Opportunities to Provide Refugees and Ugandans with Alternative Livelihood Activities in Uganda’S Kamwenge District

This report is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the support of the Office of Health, Infectious Diseases, and Nutrition, Bureau for Global Health, U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and the Office of Food for Peace, under terms of Cooperative Agreement No. AID-OAA-A-12-00005, through the Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance III Project (FANTA), managed by FHI 360. The contents are the responsibility of FHI 360 and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. Recommended Citation: Mathys, Ellen. 2016. Opportunities to Provide Refugees and Ugandans with Alternative Livelihood Activities in Uganda’s Kamwenge District. Washington, DC: FHI 360/FANTA. Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance III Project (FANTA) FHI 360 1825 Connecticut Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20009-5721 T 202-884-8000 F 202-884-8432 [email protected] www.fantaproject.org Opportunities to Provide Refugees and Ugandans with Alternative Livelihood Activities in Uganda’s Kamwenge District Contents Abbreviations and Acronyms .............................................................................................................. i Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................. 1 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 2 2. Displacement Context: Refugee Settlements and Refugee Hosting Districts -

Important Bird Areas in Uganda. Status and Trends 2008

IMPORTANT BIRD AREAS IN UGANDA Status and Trends 2008 NatureUganda The East Africa Natural History Society Important Bird Areas in Uganda Status and Trends 2008 Compiled by: Michael Opige Odull and Achilles Byaruhanga Edited by: Ambrose R. B Mugisha and Julius Arinaitwe Map illustrations by: David Mushabe Graphic designs by: Some Graphics Ltd January 2009 Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non commercial purposes is authorized without further written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Production of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written notice of the copyright holder. Citation: NatureUganda (2009). Important Bird Areas in Uganda, Status and Trends 2008. Copyright © NatureUganda – The East Africa Natural History Society About NatureUganda NatureUganda is a Non Governmental Organization working towards the conservation of species, sites and habitats not only for birds but other taxa too. It is the BirdLife partner in Uganda and a member of IUCN. The organization is involved in various research, conservation and advocacy work in many sites across the country. These three pillars are achieved through conservation projects, environmental education programmes and community involvement in conservation among others. All is aimed at promoting the understanding, appreciation and conservation of nature. For more information please contact: NatureUganda The East Africa Natural History Society Plot 83 Tufnell Drive, Kamwokya. P.O.Box 27034, Kampala Uganda Email [email protected] Website: www.natureuganda.org DISCLAIMER This status report has been produced with financial assistance of the European Union (EuropeAid/ ENV/2007/132-278. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of Birdlife International and can under no normal circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union. -

KAMWENGE BFP.Pdf

Local Government Budget Framework Paper Vote: 518 Kamwenge District Structure of Budget Framework Paper Foreword Executive Summary A: Revenue Performance and Plans B: Summary of Department Performance and Plans by Workplan C: Draft Annual Workplan Outputs for 2014/15 Page 1 Local Government Budget Framework Paper Vote: 518 Kamwenge District Foreword As mandated under Section 35 of Local Government Act (CAP 243) which makes District as Planning Authority, this BFP has accordingly been prepared to fulfill the role of Kamwenge district as required by provisions of the LG act and Budget Act 2001. In order to have a consultative budget process, a district Budget conference took place on Wednesday 27th November 2013 at Cape Hotel in Kamwenge Town and attracted participants from Sub Counties, representatives of Development partners, Religious leaders, Political leaders, District heads of departments, Civil society organizations, Members of parliament, the Media, and Financial Institutions.All aimed at the achivement of District Vision. The vision of Kamwenge district is “Improved quality of life for all the people of Kamwenge by the year 2035”, while the Mission is “to Provide coordinated and participatory service delivery by all stakeholders focusing on National and local priorities for the development of Kamwenge District”. This was part of the normal District planning cycle activities during which all stakeholders come together and review the activities so far implemented and activities and resource envelopes for the coming year. The District appreciated the low funding levels to address critical challenges like High Dropout rates in Education, Low Local Revenue base with many Co funding obligations, High HIV prevalance rate above 8.2%leading to increasing number of OVC, Low Production Levels in Home steeds with less Food security and General lack of Infrastructure developing funds. -

The National Library of Uganda: Challenges Faced in Performing Its Institutional Practices

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln Spring 2-23-2021 The National Library Of Uganda: Challenges Faced In Performing Its Institutional Practices Jane Kawalya [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Kawalya, Jane, "The National Library Of Uganda: Challenges Faced In Performing Its Institutional Practices" (2021). Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). 5073. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/5073 The National Library Of Uganda: Challenges Faced In Performing Its Institutional Practices By Jane Kawalya (PhD) 1.0 BACKGROUND The idea of establishing the NLU started in 1997. Kawalya (2009) identified several factors which led to the establishment of the NLU. Before the enactment of the National Library Act 2003, Uganda had a national library system composed of Makerere University Library (MULIB) and the Deposit Library and Documentation Center (DLDC), which were performing the functions of a national library. Meanwhile the Public Libraries Board (PLB) was performing the functions of a national library service. However, due to the decentralization of services, according to the Local Government Act 1997, the Public Libraries Act 1964 was repealed thus weakening the PLB. The public libraries were taken over by the districts which left the PLB with few functions. There was therefore a need for an institution to take over important functions which had been carried out by the PLB. It was also realized that the few responsibilities would lead to the retrenchment of the PLB staff at the headquarters. -

Proposal for Uganda

AFB.PPRC.27-28.2 AFB/PPRC.26-27/2 21 June 2021 Adaptation Fund Board Project and Programme Review Committee PROPOSAL FOR UGANDA AFB/PPRC.27-28/2 Background 1. The Operational Policies and Guidelines (OPG) for Parties to Access Resources from the Adaptation Fund (the Fund), adopted by the Adaptation Fund Board (the Board), state in paragraph 45 that regular adaptation project and programme proposals, i.e. those that request funding exceeding US$ 1 million, would undergo either a one-step, or a two-step approval process. In case of the one-step process, the proponent would directly submit a fully-developed project proposal. In the two-step process, the proponent would first submit a brief project concept, which would be reviewed by the Project and Programme Review Committee (PPRC) and would have to receive the endorsement of the Board. In the second step, the fully-developed project/programme document would be reviewed by the PPRC, and would ultimately require the Board’s approval. 2. The Templates approved by the Board (Annex 5 of the OPG, as amended in March 2016) do not include a separate template for project and programme concepts but provide that these are to be submitted using the project and programme proposal template. The section on Adaptation Fund Project Review Criteria states: For regular projects using the two-step approval process, only the first four criteria will be applied when reviewing the 1st step for regular project concept. In addition, the information provided in the 1st step approval process with respect to the review criteria for the regular project concept could be less detailed than the information in the request for approval template submitted at the 2nd step approval process. -

LG Budget Estimates 201314 Kabarole.Pdf

Local Government Budget Estimates Vote: 513 Kabarole District Structure of Budget Estimates - PART ONE A: Overview of Revenues and Expenditures B: Detailed Estimates of Revenue C: Detailed Estimates of Expenditure D: Status of Arrears Page 1 Local Government Budget Estimates Vote: 513 Kabarole District A: Overview of Revenues and Expenditures Revenue Performance and Plans 2012/13 2013/14 Approved Budget Receipts by End Approved Budget June UShs 000's 1. Locally Raised Revenues 625,911 753,885 707,744 2a. Discretionary Government Transfers 3,036,006 2,951,971 2,146,788 2b. Conditional Government Transfers 17,713,819 17,281,646 19,180,352 2c. Other Government Transfers 1,300,407 859,678 1,241,297 3. Local Development Grant 293,997 277,541 401,242 4. Donor Funding 940,390 612,164 1,064,390 Total Revenues 23,910,530 22,736,884 24,741,814 Expenditure Performance and Plans 2012/13 2013/14 Approved Budget Actual Approved Budget Expenditure by UShs 000's end of June 1a Administration 2,866,996 1,205,255 1,465,459 2 Finance 789,003 697,701 547,653 3 Statutory Bodies 859,022 697,900 594,501 4 Production and Marketing 2,565,169 2,275,097 2,385,356 5 Health 2,780,005 3,416,044 4,244,889 6 Education 12,535,605 11,733,801 12,704,178 7a Roads and Engineering 2,514,473 2,177,216 934,042 7b Water 1,137,175 411,235 848,708 8 Natural Resources 144,999 100,514 134,599 9 Community Based Services 482,606 367,505 646,895 10 Planning 280,051 147,622 173,173 11 Internal Audit 66,404 65,960 62,362 Grand Total 27,021,509 23,295,851 24,741,814 Wage Rec't: 12,796,192 12,548,253 14,518,013 Non Wage Rec't: 7,718,576 5,926,413 5,247,799 Domestic Dev't 5,566,351 4,213,639 3,911,613 Donor Dev't 940,390 607,546 1,064,390 Page 2 Local Government Budget Estimates Vote: 513 Kabarole District B: Detailed Estimates of Revenue 2012/13 2013/14 UShs 000's Approved Budget Receipts by End Approved Budget of June 1. -

Vote:022 Ministry of Tourism, Wildlife and Antiquities

Vote Performance Report Financial Year 2018/19 Vote:022 Ministry of Tourism, Wildlife and Antiquities QUARTER 4: Highlights of Vote Performance V1: Summary of Issues in Budget Execution Table V1.1: Overview of Vote Expenditures (UShs Billion) Approved Cashlimits Released Spent by % Budget % Budget % Releases Budget by End Q4 by End Q 4 End Q4 Released Spent Spent Recurrent Wage 2.086 1.043 2.086 1.989 100.0% 95.3% 95.3% Non Wage 7.259 3.621 6.775 6.765 93.3% 93.2% 99.9% Devt. GoU 6.082 2.783 5.470 5.470 89.9% 89.9% 100.0% Ext. Fin. 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% GoU Total 15.426 7.447 14.330 14.224 92.9% 92.2% 99.3% Total GoU+Ext Fin 15.426 7.447 14.330 14.224 92.9% 92.2% 99.3% (MTEF) Arrears 0.364 0.364 0.364 0.364 100.0% 100.0% 100.0% Total Budget 15.790 7.811 14.694 14.588 93.1% 92.4% 99.3% A.I.A Total 85.005 0.033 154.197 83.589 181.4% 98.3% 54.2% Grand Total 100.795 7.843 168.892 98.177 167.6% 97.4% 58.1% Total Vote Budget 100.431 7.479 168.528 97.813 167.8% 97.4% 58.0% Excluding Arrears Table V1.2: Releases and Expenditure by Program* Billion Uganda Shillings Approved Released Spent % Budget % Budget %Releases Budget Released Spent Spent Program: 1901 Tourism, Wildlife Conservation and 95.02 163.47 92.78 172.0% 97.6% 56.8% Museums Program: 1949 General Administration, Policy and Planning 5.41 5.06 5.04 93.5% 93.0% 99.5% Total for Vote 100.43 168.53 97.81 167.8% 97.4% 58.0% Matters to note in budget execution Although the approved budget for the Vote was Ushs 100.4 billion, a total of Ushs 168 billion was realized/released. -

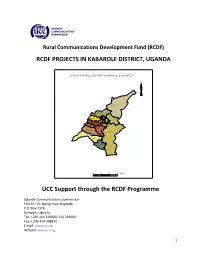

RCDF PROJECTS in KABAROLE DISTRICT, UGANDA UCC Support

Rural Communications Development Fund (RCDF) RCDF PROJECTS IN KABAROLE DISTRICT, UGANDA MAP O F KABAR O LE D ISTR IC T SHO W IN G SU B C O U N TIES N Hakiba ale Kicwa mba Western Buk uk u Busoro Karam bi Ea ste rn Mugu su So uthe rn Buh ees i Kisom oro Rutee te Kibiito Rwiimi 10 0 10 20 Km s UCC Support through the RCDF Programme Uganda Communications Commission Plot 42 -44, Spring road, Bugolobi P.O. Box 7376 Kampala, Uganda Tel: + 256 414 339000/ 312 339000 Fax: + 256 414 348832 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ucc.co.ug 1 Table of Contents 1- Foreword……………………………………………………………….……….………..…..…....….…3 2- Background…………………………………….………………………..…………..….….……………4 3- Introduction………………….……………………………………..…….…………….….…….……..4 4- Project profiles……………………………………………………………………….…..…….……...5 5- Stakeholders’ responsibilities………………………………………………….….…........…12 6- Contacts………………..…………………………………………….…………………..…….……….13 List of tables and maps 1- Table showing number of RCDF projects in Kabarole district………….…….….5 2- Map of Uganda showing Kabarole district………..………………….………...….….14 10- Map of Kabarole district showing sub counties………..…………………………..15 11- Table showing the population of Kabarole district by sub counties……….15 12- List of RCDF Projects in Kabarole district…………………………………….…….….16 Abbreviations/Acronyms UCC Uganda Communications Commission RCDF Rural Communications Development Fund USF Universal Service Fund MCT Multipurpose Community Tele-centre PPDA Public Procurement and Disposal Act of 2003 POP Internet Points of Presence ICT Information and Communications Technology UA Universal Access MoES Ministry of Education and Sports MoH Ministry of Health DHO District Health Officer CAO Chief Administrative Officer RDC Resident District Commissioner 2 1. Foreword ICTs are a key factor for socio-economic development.