Slavery & Infidelity in Montgomery C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Montana Kaimin, May 4, 1979 Associated Students of the University of Montana

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Associated Students of the University of Montana Montana Kaimin, 1898-present (ASUM) 5-4-1979 Montana Kaimin, May 4, 1979 Associated Students of the University of Montana Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper Recommended Citation Associated Students of the University of Montana, "Montana Kaimin, May 4, 1979" (1979). Montana Kaimin, 1898-present. 6834. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper/6834 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Associated Students of the University of Montana (ASUM) at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Montana Kaimin, 1898-present by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Aber Day Kegger picket proposed by labor council By MARK ELLSWORTH Max Weiss, a legal counselor at Lawry said there would be no Montana Kalmfn Reporter the University of Montana, said the "line to cross" that could cause problem with a secondary boycott trouble. He said the picket is a A meeting Wednesday night is that those involved can be held potentially "explosive issue," but between the Aber Day Kegger liable for any loss of business by the group is “trying to keep it as promoters and the Missoula the third party. cool as it can." Trades and Labor Council took But in some instances, Weiss Amid all the rising sentiment place to discuss a possible picket said, if the boycott is “in against Coors, there is still no at the kegger site to protest formational in nature, and peace word that MLAC is planning to serving Coors beer. -

CONFERENCE RECEPTION New Braunfels Civic Convention Center

U A L Advisory Committee 5 31 rsdt A N N E. RAY COVEY, Conference Chair AEP Texas PATRICK ROSE, Conference Vice Chair Corridor Title Former Texas State Representative Friday, March 22, 2019 KYLE BIEDERMANN – Texas State CONFERENCE RECEPTION Representative 7:45 - 8:35AM REGISTRATION AND BREAKFAST MICHAEL CAIN Heavy Hors d’oeuvres • Entertainment Oncor 8:35AM OPENING SESSION DONNA CAMPBELL – State Senator 7:00 pm, Thursday – March 21, 2019 TAL R. CENTERS, JR., Regional Vice Presiding: E. Ray Covey – Advisory Committee Chair President– Texas New Braunfels Civic Convention Center Edmund Kuempel Public Service Scholarship Awards CenterPoint Energy Presenter: State Representative John Kuempel JASON CHESSER Sponsored by: Wells Fargo Bank CPS Energy • Guadalupe Valley Electric Cooperative (GVEC) KATHLEEN GARCIA Martin Marietta • RINCO of Texas, Inc. • Rocky Hill Equipment Rentals 8:55AM CHANGING DEMOGRAPHICS OF TEXAS CPS Energy Alamo Area Council of Governments (AACOG) Moderator: Ray Perryman, The Perryman Group BO GILBERT – Texas Government Relations USAA Panelists: State Representative Donna Howard Former Recipients of the ROBERT HOWDEN Dan McCoy, MD, President – Blue Cross Blue Shield of Texas Texans for Economic Progress Texan of the Year Award Steve Murdock, Former Director – U.S. Census Bureau JOHN KUEMPEL – Texas State Representative Pia Orrenius, Economist – Dallas Federal Reserve Bank DAN MCCOY, MD, President Robert Calvert 1974 James E. “Pete” Laney 1996 Blue Cross Blue Shield of Texas Leon Jaworski 1975 Kay Bailey Hutchison 1997 KEVIN MEIER Lady Bird Johnson 1976 George Christian 1998 9:50AM PROPERTY TAXES AND SCHOOL FINANCE Texas Water Supply Company Dolph Briscoe 1977 Max Sherman 1999 Moderator: Ross Ramsey, Co-Founder & Exec. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season

// BOSTON T /?, SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA THURSDAY B SERIES EIGHTY-SEVENTH SEASON 1967-1968 wgm _«9M wsBt Exquisite Sound From the palace of ancient Egyp to the concert hal of our moder cities, the wondroi music of the harp hi compelled attentio from all peoples and a countries. Through th passage of time man changes have been mac in the original design. Tl early instruments shown i drawings on the tomb < Rameses II (1292-1225 B.C were richly decorated bv lacked the fore-pillar. Lato the "Kinner" developed by tl Hebrews took the form as m know it today. The pedal hai was invented about 1720 by Bavarian named Hochbrucker an through this ingenious device it b came possible to play in eight maj< and five minor scales complete. Tods the harp is an important and familij instrument providing the "Exquisi* Sound" and special effects so importai to modern orchestration and arrang ment. The certainty of change mak< necessary a continuous review of yoi insurance protection. We welcome tl opportunity of providing this service f< your business or personal needs. We respectfully invite your inquiry CHARLES H. WATKINS & CO. Richard P. Nyquist — Charles G. Carleton 147 Milk Street Boston, Massachusetts Telephone 542-1250 OBRION, RUSSELL & CO. Insurance of Every Description EIGHTY-SEVENTH SEASON 1967-1968 BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ERICH LEINSDORF Music Director CHARLES WILSON Assistant Conductor THE TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA INC. HENRY B. CABOT President TALCOTT M. BANKS Vice-President JOHN L. THORNDIKE Treasurer PHILIP K. ALLEN E. MORTON JENNINGS JR ABRAM BERKOWITZ EDWARD M. KENNEDY THEODORE P. -

Chapter 9 Quiz

Name: ___________________________________ Date: ______________ 1. The diffusion of authority and power throughout several entities in the executive branch and the bureaucracy is called A) the split executive B) the bureaucratic institution C) the plural executive D) platform diffusion 2. A government organization that implements laws and provides services to individuals is the A) executive branch B) legislative branch C) judicial branch D) bureaucracy 3. What is the ratio of bureaucrats to Texans? A) 1 bureaucrat for every 1,500 Texas residents B) 1 bureaucrat for every 3,500 Texas residents C) 1 bureaucrat for every 4,000 Texas residents D) 1 bureaucrat for every 10,000 Texas residents 4. The execution by the bureaucracy of laws and decisions made by the legislative, executive, or judicial branch, is referred to as A) implementation B) diffusion C) execution of law D) rules 5. How does the size of the Texas bureaucracy compare to other states? A) smaller than most other states B) larger than most other states C) about the same D) Texas does not have a bureaucracy 6. Standards that are established for the function and management of industry, business, individuals, and other parts of government, are called A) regulations B) licensing C) business laws D) bureaucratic law 7. What is the authorization process that gives a company, an individual, or an organization permission to carry out a specific task? A) regulations B) licensing C) business laws D) bureaucratic law 8. The carrying out of rules by an agency or commission within the bureaucracy, is called A) implementation B) rule-making C) licensing D) enforcement 9. -

Ranching Catalogue

Catalogue Ten –Part Four THE RANCHING CATALOGUE VOLUME TWO D-G Dorothy Sloan – Rare Books box 4825 ◆ austin, texas 78765-4825 Dorothy Sloan-Rare Books, Inc. Box 4825, Austin, Texas 78765-4825 Phone: (512) 477-8442 Fax: (512) 477-8602 Email: [email protected] www.sloanrarebooks.com All items are guaranteed to be in the described condition, authentic, and of clear title, and may be returned within two weeks for any reason. Purchases are shipped at custom- er’s expense. New customers are asked to provide payment with order, or to supply appropriate references. Institutions may receive deferred billing upon request. Residents of Texas will be charged appropriate state sales tax. Texas dealers must have a tax certificate on file. Catalogue edited by Dorothy Sloan and Jasmine Star Catalogue preparation assisted by Christine Gilbert, Manola de la Madrid (of the Autry Museum of Western Heritage), Peter L. Oliver, Aaron Russell, Anthony V. Sloan, Jason Star, Skye Thomsen & many others Typesetting by Aaron Russell Offset lithography by David Holman at Wind River Press Letterpress cover and book design by Bradley Hutchinson at Digital Letterpress Photography by Peter Oliver and Third Eye Photography INTRODUCTION here is a general belief that trail driving of cattle over long distances to market had its Tstart in Texas of post-Civil War days, when Tejanos were long on longhorns and short on cash, except for the worthless Confederate article. Like so many well-entrenched, traditional as- sumptions, this one is unwarranted. J. Evetts Haley, in editing one of the extremely rare accounts of the cattle drives to Califor- nia which preceded the Texas-to-Kansas experiment by a decade and a half, slapped the blame for this misunderstanding squarely on the writings of Emerson Hough. -

Texas GOP and Its Big Three Bag Enterprise-Fund Millions

Public-Private Partnership: April 8, 2013 Texas GOP and Its Big Three Bag Enterprise-Fund Millions Companies Winning $307 Million in State Awards Contribute $5.3 Million to Perry, Dewhurst, Straus and Their Party he Republican Party of Texas and three Lexicon Pharmaceuticals. Lexicon is a partner in state politicians who control the Texas the Texas Institute for Genomic Medicine Enterprise Fund (TEF) collected $5.3 (TIGM), which received an unsurpassed $50 T 3 million in political money from donors affiliated million TEF award in 2005. TIGM is a prime with $307 million in Enterprise Fund grants. example of how TEF fabricates its job-creation claims.4 An analysis of 106 Enterprise Fund awardees finds that political committees, executives or Dewhurst collected $1.3 million in TEF money. investors1 associated with 38 state-funded His top TEF contributor is James Leininger, who projects contributed $3.6 million since 2000 to invested in TIGM and the biotech firm Gradalis, Governor Rick Perry, Lieutenant Governor Inc. Gradalis’ investors made huge investments David Dewhurst and House Speaker Joe in Dewhurst and Perry and then landed Straus—the very officials who oversee TEF. unprecedented grants from three major Texas TEF-linked contributors gave almost $1.7 slush funds. million more to the Republican Party of Texas. The No. 1 recipient of TEF political funds is Big Recipients of Enterprise-Fund Cash Governor Perry, who lobbied to create this Enterprise Fund Top TEF taxpayer-financed job fund in 2003. The Recipient Contributions Contributor governor has collected more than $2 million in Rick Perry $2,053,449 Robert McNair TEF-tied contributions, up from the $1.7 million that he had collected two years ago.2 Repub. -

Baselice Poll – Dan Patrick Vs David Dewhurst

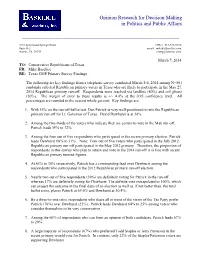

Opinion Research for Decision Making in Politics and Public Affairs ________________________________________________________________________________ 4131 Spicewood Springs Road Office: 512-345-9720 Suite O-2 email: [email protected] Austin, TX 78759 [email protected] March 7, 2014 TO: Conservative Republicans of Texas FR: Mike Baselice RE: Texas GOP Primary Survey Findings The following are key findings from a telephone survey conducted March 5-6, 2014 among N=501 randomly selected Republican primary voters in Texas who are likely to participate in the May 27, 2014 Republican primary run-off. Respondents were reached via landline (80%) and cell phone (20%). The margin of error to these results is +/- 4.4% at the 0.95 confidence level. All percentages are rounded to the nearest whole percent. Key findings are: 1. With 55% on the run-off ballot test, Dan Patrick is very well-positioned to win the Republican primary run-off for Lt. Governor of Texas. David Dewhurst is at 34%. 2. Among the two-thirds of the voters who indicate they are certain to vote in the May run-off, Patrick leads 59% to 32%. 3. Among the four out of five respondents who participated in the recent primary election, Patrick leads Dewhurst 60% to 31%. Note: Four out of five voters who participated in the July 2012 Republican primary run-off participated in the May 2012 primary. Therefore, the proportion of respondents in this survey who plan to return and vote in the 2014 run-off is in line with recent Republican primary turnout figures. 4. At 63% to 30% respectively, Patrick has a commanding lead over Dewhurst among the respondents who participated in the 2012 Republican primary run-off election. -

Chicago Symphony Orchestra JEAN MARTINON, Music Director and Conductor Soloist: JOHN BROWNING, Pianist

1965 Eighty-seventh Season 1966 UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Charles A. Sink, President Gail W. Rector, Executive Director Lester McCoy, Conductor First Concert Eighty-seventh Annual Choral Union Series Complete Series 3480 Chicago Symphony Orchestra JEAN MARTINON, Music Director and Conductor Soloist: JOHN BROWNING, Pianist SATURDAY EVENING, OCTOBER 9, 1965, AT 8 :30 HILL AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN PROGRAM Overture to Il Matrimonio segreto . CIMAROSA Symphony No.4 in A major ("Italian") Op. 90 MENDELSSOHN Allegro vivace Andante con moto Saltarello: presto INTERMISSION Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 38 BARBER Allegro appassionata Canzona: moderato Allegro molto JOHN BROWNING Suite from the Ballet L'Oiseau feu (The Firebird) STRAVINSKY Introduction: The Firebird and Her Dance Dance of the Princesses Infernal Dance of Kastchei Berceuse Finale A R S LON G A V I T A BREVIS PROGRAM NOTES Overture to Il Matrimonio segreto DOMENICO CIMAROSA Cimarosa was one of the most prolific of Italian opera composers during the last quarter of the eighteenth century. For a period of time (1787-1791) he served as chamber composer to Catherine II of Russia and composed two operas for production in St. Petersburg in addition to a quantity of instrumental and vocal wo rks. He also succeeded Salieri as Kapell meister at the Austrian court under Leopold II. It was while he was in the service of Leopold that he composed The Secret Marriage (II M atrirnonio segreto), his only opera to maintain a place in the active operatic repertory. This lively example of Italian buffo was very successful from the first performance at the Burg Theater in Vienna, February 7, 1792. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 87, 1967-1968

1 J MIT t / ^ii "fv :' • "" ..."?;;:.»;:''':•::•> :.:::«:>:: : :- • :/'V *:.:.* : : : ,:.:::,.< ::.:.:.: .;;.;;::*.:?•* :-: ;v $mm a , '.,:•'•- % BOSTON ''•-% m SYMPHONY v. vi ORCHESTRA TUESDAY A SERIES EIGHTY-SEVENTH SEASON 1967-1968 -^^VTW-s^ Exquisite Sound From the palaces of ancient Egypt to the concert halls of our modern cities, the wondrous music of the harp has compelled attention from all peoples and all countries. Through this passage of time many changes have been made in the original design. The early instruments shown in drawings on the tomb of Rameses II (1292-1225 B.C.) were richly decorated but lacked the fore-pillar. Later the "Kinner" developed by the Hebrews took the form as we know it today. The pedal harp was invented about 1720 by a Bavarian named Hochbrucker and through this ingenious device it be- came possible to play in eight major and five minor scales complete. Today the harp is an important and familiar instrument providing the "Exquisite Sound" and special effects so important to modern orchestration and arrange- ment. The certainty of change makes necessary a continuous review of your insurance protection. We welcome the opportunity of providing this service for your business or personal needs. We respectfully invite your inquiry CHARLES H. WATKINS & CO. Richard P. Nyquist — Charles G. Carleton 147 Milk Street Boston, Massachusetts Telephone 542-1250 OBRION, RUSSELL & CO. Insurance of Every Description EIGHTY-SEVENTH SEASON 1967-1968 BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ERICH LEINSDORF Music Director CHARLES WILSON Assistant Conductor THE TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA INC. HENRY B. CABOT President TALCOTT M. BANKS Vice-President JOHN L. THORNDIKE Treasurer PHILIP K. -

Policy Report Texas Fact Book 2008

Texas Fact Book 2 0 0 8 L e g i s l a t i v e B u d g e t B o a r d LEGISLATIVE BUDGET BOARD EIGHTIETH TEXAS LEGISLATURE 2007 – 2008 DAVID DEWHURST, JOINT CHAIR Lieutenant Governor TOM CRADDICK, JOINT CHAIR Representative District 82, Midland Speaker of the House of Representatives STEVE OGDEN Senatorial District 5, Bryan Chair, Senate Committee on Finance ROBERT DUNCAN Senatorial District 28, Lubbock JOHN WHITMIRE Senatorial District 15, Houston JUDITH ZAFFIRINI Senatorial District 21, Laredo WARREN CHISUM Representative District 88, Pampa Chair, House Committee on Appropriations JAMES KEFFER Representative District 60, Eastland Chair, House Committee on Ways and Means FRED HILL Representative District 112, Richardson SYLVESTER TURNER Representative District 139, Houston JOHN O’Brien, Director COVER PHOTO COURTESY OF SENATE MEDIA CONTENTS STATE GOVERNMENT STATEWIDE ELECTED OFFICIALS . 1 MEMBERS OF THE EIGHTIETH TEXAS LEGISLATURE . 3 The Senate . 3 The House of Representatives . 4 SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES . 8 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES STANDING COMMITTEES . 10 BASIC STEPS IN THE TEXAS LEGISLATIVE PROCESS . 14 TEXAS AT A GLANCE GOVERNORS OF TEXAS . 15 HOW TEXAS RANKS Agriculture . 17 Crime and Law Enforcement . 17 Defense . 18 Economy . 18 Education . 18 Employment and Labor . 19 Environment and Energy . 19 Federal Government Finance . 20 Geography . 20 Health . 20 Housing . 21 Population . 21 Social Welfare . 22 State and Local Government Finance . 22 Technology . 23 Transportation . 23 Border Facts . 24 STATE HOLIDAYS, 2008 . 25 STATE SYMBOLS . 25 POPULATION Texas Population Compared with the U .s . 26 Texas and the U .s . Annual Population Growth Rates . 27 Resident Population, 15 Most Populous States . -

ROCKPORT CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL PROGRAMS 1997-2001 LOCATION: ROCKPORT ART ASSOCIATION 1997 June 12-July 6, 1997 David Deveau, Artistic Director

ROCKPORT CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL PROGRAMS 1997-2001 LOCATION: ROCKPORT ART ASSOCIATION 1997 June 12-July 6, 1997 David Deveau, artistic director Thursday, June 12, 1997 Opening Night Gala Concert & Champagne Reception The Piano Virtuoso Recital Series Russell Sherman, piano Ricordanza, No. 9 from The Transcendental Etudes Franz Liszt (1811-86) Wiegenlied (Cradle-song) Liszt Sonata in B minor Liszt Sech Kleine Klavierstucke (Six Piano Piece), OP. 19 (1912) Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951) Sonata No. 23 in F minor, Op. 57 “Appassionata” Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Friday, June 13, 1997 The International String Quartet Series The Shanghai Quartet Quartet in G major, Op. 77, No. 1, “Lobkowitz” Franz Josef Haydn (1732-1809) Poems from Tang Zhou Long (b.1953) Quartet No. 14 in D minor, D.810 “Death and the Maiden” Franz Schubert (1797-1828) Saturday, June 14, 1997 Chamber Music Gala Series Figaro Trio Trio for violin, cello and piano in C major, K.548 (1788) Wolfgang A. Mozart (1756-91) Duo for violin and cello, Op. 7 (1914) Zoltan Kodaly (1882-1967) Trio for violin, cello and piano in F minor, Op. 65 (1883) Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904) Sunday, June 15, 1997 Chamber Music Gala Series Special Father’s Day Concert Richard Stoltzman, clarinet Janna Baty, soprano (RCMF Young Artist) | Andres Diaz, cello Meg Stoltzman, piano | Elaine Chew, piano (RCMF Young Artist) | Peter John Stoltzman, piano David Deveau, piano The Great Panjandrum (1989) Peter Child (b.1953) Sonata for clarinet and piano (1962) Francis Poulenc (1899-1964( Jazz Selections Selected Waltzes and Hungarian Dances for piano-four hands Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Trio in A minor for clarinet, cello and piano, Op. -

Bonnie and Clyde: the Making of a Legend by Karen Blumenthal, 2018, Viking Books for Young Readers

Discussion and Activity Guide Bonnie and Clyde: The Making of a Legend by Karen Blumenthal, 2018, Viking Books for Young Readers BOOK SYNOPSIS “Karen Blumenthal’s breathtaking true tale of love, crime, and murder traces Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow’s wild path from dirt-poor Dallas teens to their astonishingly violent end and the complicated legacy that survives them both. This is an impeccably researched, captivating portrait of an infamous couple, the unforgivable choices they made, and their complicated legacy.” (publisher’s description from the book jacket) ABOUT KAREN BLUMENTHAL “Ole Golly told me if I was going to be a writer I better write down everything … so I’m a spy that writes down everything.” —Harriet the Spy, Louise Fitzhugh Like Harriet M. Welsch, the title character in Harriet the Spy, award-winning author Karen Blumenthal is an observer of the world around her. In fact, she credits the reading of Harriet the Spy as a child with providing her the impetus to capture what was happening in the world around her and become a writer herself. Like most authors, Blumenthal was first a reader and an observer. She frequented the public library as a child and devoured books by Louise Fitzhugh and Beverly Cleary. She says as a child she was a “nerdy obnoxious kid with glasses” who became a “nerdy obnoxious kid with contacts” as a teen. She also loved sports and her hometown Dallas sports teams as a kid and, consequently, read books by sports writer, Matt Christopher, who inspired her to want to be a sports writer when she grew up.