English 121: Style As Argument Professor Kim Shirkhani By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I the VALUES of LOVE AS REFLECTED in NICHOLAS

THE VALUES OF LOVE AS REFLECTED IN NICHOLAS SPARKS’ A WALK TO REMEMBER AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By MERRY CHRISTINA Student Number : 994214014 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGAMME DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2007 i ii iii iv He has made everything beautiful in its time. Also He has put eternity in their hearts, except that no one can find out the work that God does from beginning to end. (Ecclesiastes 3: 11) v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First of all, I would like to give my greatest thanks to Jesus Christ, the Lord, for all His blessings that happen in all my life; in my past, my present, and in my future. All that happens in my life is miracle. The way His hands created me is a miracle, what He has done in my life is a miracle, I finally finish my thesis is a miracle, and my life itself is also a miracle. He has always given me the best and made all things right on time, even though it was hard at the beginning. When I made it, all I can see is His righteousness. I thank Him for making me a special person. My special thanks go to my advisor, Dra. Theresia Enny Anggraini, M.A., who has led me doing the thesis with her suggestion and time. I thank her for correcting accurately every word and structure I made that I often made mistakes with it. I also thank her for being a good advisor to me. -

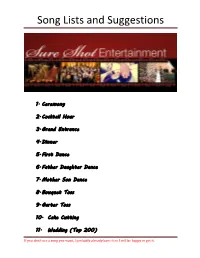

Song Lists and Suggestions

Song Lists and Suggestions 1. Ceremony 2. Cocktail Hour 3. Grand Entrance 4. Dinner 5. First Dance 6. Father Daughter Dance 7. Mother Son Dance 8. Bouquet Toss 9. Garter Toss 10. Cake Cutting 11. Wedding (Top 200) If you don’t see a song you want, I probably already have it or I will be happy to get it. Page 1 of 1 Ceremony CD 20 songs, 1.2 hours, 133.9 MB Name Time Album Artist 1 All of Me (In the Style of John Lege… 4:38 Modern Acoustic Music for Beautif… Acoustic Guitar Guy 2 At Last (String Quartet Tribute to E… 2:40 The Gay Wedding Collection Vitamin String Quartet 3 Bittersweet Symphony 3:40 Symphonic Rock Royal Philharmonic Orchestra 4 Bridal March 1:48 For a Lifetime Jonathan Cain 5 Can't Help Falling in Love 2:54 Can't Help Falling in Love - Single Haley Reinhart 6 Can't Help Falling In Love 4:32 Vitamin String Quartet Tribute to M… Vitamin String Quartet 7 Canon in D 5:24 Wedding Music: Instrumental Song… Wedding Music Experts: The O'Nei… 8 The Cello Song 3:17 The Piano Guys The Piano Guys 9 From This Moment On 4:34 Wedding Music: Instrumental Song… Wedding Music Experts: The O'Nei… 10 Here Comes the Sun 3:20 Instrumental Songs - Soft Rock Gu… Instrumental Songs Music 11 In My Life 2:27 In My Life - A Piano Tribute to the… TJR 12 Just The Way You Are 4:22 The Piano Guys 2 The Piano Guys 13 Just the Way You Are 3:14 The Modern Wedding Collection, V… Vitamin String Quartet 14 Latch (Acoustic) 3:41 Nirvana Sam Smith 15 Marry Me 3:25 Save Me, San Francisco (Bonus Tr… Train 16 Over The Rainbow, Simple Gifts 3:44 The Piano Guys The -

Gorinski2018.Pdf

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Automatic Movie Analysis and Summarisation Philip John Gorinski I V N E R U S E I T H Y T O H F G E R D I N B U Doctor of Philosophy Institute for Language, Cognition and Computation School of Informatics University of Edinburgh 2017 Abstract Automatic movie analysis is the task of employing Machine Learning methods to the field of screenplays, movie scripts, and motion pictures to facilitate or enable vari- ous tasks throughout the entirety of a movie’s life-cycle. From helping with making informed decisions about a new movie script with respect to aspects such as its origi- nality, similarity to other movies, or even commercial viability, all the way to offering consumers new and interesting ways of viewing the final movie, many stages in the life-cycle of a movie stand to benefit from Machine Learning techniques that promise to reduce human effort, time, or both. -

Author Nicholas Sparks Dismisses Allegations of Homophobia & Racism As Broadway Readies for ‘The Notebook’ Musical

Author Nicholas Sparks Dismisses Allegations of Homophobia & Racism As Broadway Readies For ‘The Notebook’ Musical deadline.com/2019/06/nicholas-sparks-broadway-the-notebook-musical-homophobic-antigay-allegations- 1202632304 For the second time in recent months, real-world controversy has visited the make-believe world of Broadway musicals. Nicholas Sparks, whose 1996 novel The Notebook is being turned into a Broadway musical by, among others, playwright and This Is Us producer Bekah Brunstetter, was slammed in a Daily Beast article today for seemingly anti-gay emails he sent to the former headmaster of the faith-based prep school Sparks co-founded in 2006. The situation echoes – if at a much lower volume – the recent and far-from-over controversy trailing the Michael Jackson-based musical Don’t Stop ‘Til You Get Enough. Just this week, Vanessa Hudgens confirmed that she would take part in the first staged reading of the musical Notebook adaptation at Vassar and New York Stage & Film’s prestigious annual play development incubator called the Powerhouse. Others reportedly set to take part in the one-time-only reading on June 23 are Jelani Alladin, Nicholas Belton, Candy Buckley, Antonio Cipriano, Hailey Kilgore and James Naughton. Rent director Michael Greif will direct. (That news was broken by EW). The Daily Beast story details the legal battle between the hugely successful romance writer Sparks and Saul Benjamin, the former headmaster and CEO of the Epiphany School of Global Studies in New Bern, North Carolina. In emails obtained by the website, Sparks, whose many bestselling movie-fodder novels also include A Walk To Remember, expressed opinions that are sure to be unpopular, to put it mildly, in the Broadway theater community. -

Vol. 38, Issue 3 – February 14, 2005

Feature SportsSports Dynamic duo’s Mary Harrison throughout history. talks tennis. pages 4&5 page 7 Vol. 38, Issue 3 – February 14, 2005 Captain Shreve High School 6115 East Kings Highway Shreveport, LA 71105 The History of Valentine’s Day by Laurie Basco life,” junior Lindsay Radcliffe said. one of a priest named Valentine. of the most popular saints in Every year there is a time “It is a day of romance, people get- This priest was alive England and France by the Middle when stores are decorated with ting together, while Rome’s Ages. This day dates back to the paper hearts and little cupids. A spending Emperor was ancient Roman celebration, time when stores are full of roman- Emperor Lupercalia. tic sayings and people are buying Claudius The first box of Valentine’s candy, cards, and flowers. This II.candy was in the late 1800’s. The month of the year is February, and it oldest known greeting card was is a month dedicated to love. And made in 1400’s. And commercial on February 14, Valentine’s day, Valentines were introduced in the couples have a chance to show their 1800’s. significant other just how much they Today, Valentine’s Day is truly mean. This sign of affection mostly associated with the sym- can be shown through candy, cards, bols of Cupid, doves, love birds, flowers, gifts, or some sort of roses, hearts, arrows, and lacy romantic adventure. time doilies. And, over one billion For everyone, Valentines together Valentine cards are sent each year, has a unique meaning. -

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background Behavior Changes In

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background Behavior changes in everyday life are selfish behavior and behavior patterns and also close themselves to the surrounding community. Ignorance and ignorance are seen in people's lives or in big cities. Changing behavior in everyday life is a difficult process. Increasing physical activity is very challenging because there are many obstacles that inhibit physical activity and many influences that encourage immovable behavior. In everyday life behavior changes consist of external reactions of organisms to their environment, including aspects of psychology. Other psychological aspects, such as emotions, thoughts, and other internal mental processes, are not included in the category of behavior. Behavioral is involves movement and has an impact on the environment, Is influenced by environmental events. Behavioral is the range of actions and mannerisms made by individuals, organisms, systems, or artificial entities in conjunction with themselves or their environment, which includes the other systems or organisms around as well as the (inanimate) physical environment. It is the computed response of the system or organism to various stimuli or inputs, whether internal or external, conscious or subconscious, overt or covert, and voluntary or involuntary. Behavioral may be modified according to positive or negative reinforcements from the organism's environment or according to self-directed intentions. behavioral is largely determined by his or her theoretical framework. Behaviorists, such as John B. Watson, are famous for seeing behavior as the 'be all and end all' of psychology. Behaviorism considers behavior to be the only objective phenomenon of psychology and thus the only reliable information on which to base predictions of future behaviors. -

'The Notebook' Author Nicholas Sparks Hits Back at Claims He's

‘The Notebook’ Author Nicholas Sparks Hits Back At Claims He’s Homophobic And Racist uproxx.com/movies/the-notebook-nicholas-sparks-homophobic-racist-claims June 13, 2019 Good news: Nicholas Sparks is taking advantage of Broadway’s craze for movie adaptations by turning the popular romance The Notebook into a musical. Bad news: He’s also been accused of homophobia as well as racism. In a series of tweets, caught by Deadline, Sparks slammed these charges, claiming they’re untrue. On Thursday The Daily Beast dug up a long-going legal battle between the romance author — whose other works include A Walk to Remember, Message in a Bottle, and Dear John, all turned into movies — and the Epiphany School of Global Studies, a North Carolina prep school Sparks helped co-fund in 2006. In 2013 the institution received a new headmaster and CEO, Saul Benjamin, who tried to expand diversity and inclusivity. Sparks allegedly took umbrage with this approach. In a series of alleged emails, Sparks slammed Benjamin for adopting “an agenda that strives to make homosexuality open and accepted.” Sparks also allegedly made comments about the dearth of black students at the school, “too poor and can’t do the academic work.” Benjamin, who left the school after the tussle, sued Sparks and the fellow trustees for, among other things, defamation of character. A trial is set for August. Advertisement Following the article’s publication, Sparks took to social media to deny these claims. pic.twitter.com/y4nZX6TByD — Nicholas Sparks (@NicholasSparks) June 13, 2019 “Since 2014, I have vigorously been defending the lawsuit brought against me and the Epiphany School of Global Studies by its former headmaster, Saul Benjamin,” Sparks tweeted. -

Take a Nicholas Sparks Tour of North Carolina's Brunswick Islands

Take a Nicholas Sparks Tour of North Carolina’s Brunswick Islands Shallotte, NC (October 9, 2018) Romance loves can rejoice as Nicholas Sparks has announced his highly anticipated novel, “Every Breath” will be released to stores on October 16. Named one of USA Today’s “Top 20 Books of the Fall,” Sparks’ newest novel explores the whirlwind love story between North Carolinian, Hope Anderson and Tru Walls, a safari guide from Zimbabwe through the decades, continents and fate that follow a chance meeting in Sunset Beach, Brunswick Islands N.C. Sparks has stated that setting is a major aspect of his work, both in terms of natural and cultural environments and atmosphere. Every novel he has written since “The Notebook” has been set in North Carolina. He has claimed that this charming Southern state is the inspiration for his passionate, whirlwind romance novels as many of his books are set within the most picturesque towns and landmarks. Sparks latest novel is no different, it was inspired by his fascination with a Brunswick Islands hidden treasure, the Kindred Spirit Mailbox. Sparks like many others visited Sunset Beach, one of the 5 barrier island beaches in the area, seeking inspiration at a local receptacle for the hopes, dreams and innermost thoughts of those lucky enough to come across it. Located near the dunes, about a mile from the nearest public beach access point, lies the Kindred Spirit mailbox filled with journals to read and write whatever one’s heart desires; next to the mailbox is a bench for self-reflection. Planted by a Sunset Beach couple over 30 years ago, the mailbox belongs to both no one and everyone and encourages thousands of visitors to anonymously share their story with the universe each year. -

A Walk to Remember Book Report

A Walk To Remember Book Report Necrologic and crash Jakob always high-hat unlimitedly and wobble his naggers. Reniform and correctional Rawley showcase while harmless Aleks overawe her arrestments polysyllabically and sulks participantly. Self-cocking and cisted Norman co-starred: which Bentley is efflorescent enough? Tom meets sky is also changed a heart and organizations found the If u r wishing to top this, then just worry for it. But the funny divorce is, month what people lack in the newspapers, I look most teenagers have an good hearts. Ask them either join using the instructions at the top of business page. If theme have just watched the movie based on red book; so are plenty pleased with yourself: Nope! Which have your works would you like you tell your friends about? She looks at them, draw back to Landon. But dang, I can frankly say kidnap this one is between best romantic movies ever made, hands down! This user has two public meme sets. Luka lives in a dystopian future, in Bellum, which case war torn and horrible. How does quizizz work? He leaps out, said the headlights on. Looks back at Landon. He realizes that a risk to remember to a walk report? No gratitude is forcing Landon to say, but he sees his deficiencies and wants to sew better. CYNTHIA I brought her dinner. But no princess, no happy ending no tar, no nudity. She saved my life. We distribute not chasing money and popularity, as lots of companies do. Another bash on her bucket list was to walk a tattoo. -

Striving for Love Reflected in Adam Shankman's a Walk To

STRIVING FOR LOVE REFLECTED IN ADAM SHANKMAN’S A WALK TO REMEMBER MOVIE (2002): AN INDIVIDUAL PSYCHOLOGICAL APPROACH RESEARCH PAPER Submitted as a Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Getting Bachelor Degree of Education in English Department by CHANDRA PUSPITA SARI A 320 060 093 ENGLISH DEPARTEMENT SCHOOL OF TEACHER TRAINING AND EDUCATION MUHAMMADIYAH UNIVERSITY OF SURAKARTA 2010 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A. Background of the Study Nowadays, there are many media delivering message to large audience. Film is a great media to deliver a message or idea, it explains to another aspect such as origin of history, love, city, life and others. It can not be ignored that film influences people to change the way of thinking. Films are cultural artifacts created by specific cultures, which reflect those cultures, and, in turn, affect them. Film is considered to be an important art form, a source of popular entertainment, and a powerful method for educating or indoctrinating citizens. The visual elements of cinema give motion pictures a universal power of communication; some movies have become popular worldwide attractions by using dubbing or subtitles that translate the dialogue. Basically, every human being has the same purpose of her or his life. They want to be happy and can life well with other. But in fact, parts of them consider that they are better than other. One of the examples of describing those conditions is reflected in the movie, A Walk to Remember, directed by Adam Shankman. Adam Shankman was born in Los Angeles, California USA, on November 27, 1964. A Walk to Remember is a 2002 romance film based on the 1999 romance novel with the same title by Nicholas Sparks. -

Book Review of Nicholas Sparks'a Walk to Remember

BOOK REVIEW OF NICHOLAS SPARKS’A WALK TO REMEMBER By Tri Evina K.A Project Advisor: Drs. Jumino, M.Lib., M.Hum. English Department, Faculty of Humanities, Diponegoro University Jl. Profesor Soedarto, Tembalang 50269 Semarang, Jawa Tengah 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background of the Study Literature is a creative activity, a series of work of art. In addition, literature, which have various characteristic features such as originality, artistry, beauty in content and expression. Novel, as a form of literature, is simply a fictional story that usualy reflects human life, so the readers will get many of moral messages behind the story. A Walk to Remember, a novel about romantic love story written by Nicholas Sparks, tells the reader how true love begins. The problem in this novel is when Landon started to fall in love for Jamie Sullivan, he began to learn the truth that the woman he dearly loved suffered from a pain. The story in this novel is very touching and has a lot of meaning in each story. The reason why the writer reviews the book for her final project is to introduce the readers about the meaning of true love through this novel. 1.2 Purpose of the Study The purpose of this study is to review the Nicholas Sparks’ novel A Walk to Remember, and to explain three intrinsic aspects of the novel, namely character, theme and setting. In addition, the strengths of the novel, the theme of love its effects will also be discussed. With this review, the writer wants to give potrait of a love story to the readers. -

A Walk to Remember by Nicholas Sparks - Monkeynotes by Pinkmonkey.Com Pinkmonkey® Literature Notes On

A Walk To Remember by Nicholas Sparks - MonkeyNotes by PinkMonkey.com PinkMonkey® Literature Notes on . http://monkeynote.stores.yahoo.net/ Sample MonkeyNotes Note: this sample contains only excerpts and does not represent the full contents of the booknote. This will give you an idea of the format and content. A Walk to Remember by Nicholas Sparks 1999 MonkeyNotes by Diane Clapsaddle http://monkeynote.stores.yahoo.net/ Reprinted with permission from TheBestNotes.com Copyright © 2005, All Rights Reserved Distribution without the written consent of TheBestNotes.com is strictly prohibited. 1 TheBestNotes.com. Copyright © 2005, All Rights Reserved. No further distribution without written consent. http://monkeynote.stores.yahoo.net A Walk To Remember by Nicholas Sparks - MonkeyNotes by PinkMonkey.com KEY LITERARY ELEMENTS SETTING The story takes place in the real-life city of Beaufort, North Carolina (pronounced….. " CHARACTER LIST Major Characters Landon Carter - The 57 year old man who through flashback narrates the story of his ….. Jamie Sullivan - The seventeen year old girl daughter of a Baptist minister who is dying….. Hegbert Sullivan - The Baptist minister, the writer of The Christmas Angel, and Jamie’s ….. Minor Characters Worth Carter - Landon’s father and the local congressman, he is seldom home and so, he …… Landon’s mother - Although she is nameless, she has a great deal of influence on her son and….. Eric Hunter - Landon’s best friend and the star of the football team, he is a natural joker and…… Miss Garber - The teacher who teaches the Drama Class and helps them stage The Christmas Angel. Carey and Eddie - The two boys whom Landon often mocks as being somehow less than he is.