Vii. Tidal Wave

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Innsmouth Conspiracy

Campaign Guide THE INNSMOUTH CONSPIRACY randomized facedown. Keys can enter play via several different card In the Deep, They Thrive effects, and they are usually placed on an enemy, location, or story “It was a town of wide extent and dense construction, yet one asset. Keys can be acquired in any of three ways: with a portentous dearth of visible life.” Æ If a location with a key on it has no clues, an investigator may take – H. P. Lovecraft,The Shadow over Innsmouth control of each of the location’s keys as a ability. The Innsmouth Conspiracy is a campaign for Arkham Horror: The Æ If an investigator causes an enemy with a key on it to leave play, that Card Game for 1–4 players. The Innsmouth Conspiracy deluxe investigator must take control of each of the keys that were on that expansion contains two scenarios: “The Pit of Despair” and “The enemy. (If it leaves play through some other means, place its keys Vanishing of Elina Harper.” These scenarios can be played on their on its location.) own or combined with the six Mythos Packs in The Innsmouth Æ Some card effects may allow an investigator to take control of keys Conspiracy cycle to form a larger eight‑part campaign. in other ways. Additional Rules and Clarifications When an investigator takes control of a key, they flip it faceup (if it is facedown) and place it on their investigator card. If an investigator who controls one or more keys is eliminated, place each of their keys on Keys their location. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Versions Title Artist Versions #1 Crush Garbage SC 1999 Prince PI SC #Selfie Chainsmokers SS 2 Become 1 Spice Girls DK MM SC (Can't Stop) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue SF 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue MR (Don't Take Her) She's All I Tracy Byrd MM 2 Minutes To Midnight Iron Maiden SF Got 2 Stars Camp Rock DI (I Don't Know Why) But I Clarence Frogman Henry MM 2 Step DJ Unk PH Do 2000 Miles Pretenders, The ZO (I'll Never Be) Maria Sandra SF 21 Guns Green Day QH SF Magdalena 21 Questions (Feat. Nate 50 Cent SC (Take Me Home) Country Toots & The Maytals SC Dogg) Roads 21st Century Breakdown Green Day MR SF (This Ain't) No Thinkin' Trace Adkins MM Thing 21st Century Christmas Cliff Richard MR + 1 Martin Solveig SF 21st Century Girl Willow Smith SF '03 Bonnie & Clyde (Feat. Jay-Z SC 22 Lily Allen SF Beyonce) Taylor Swift MR SF ZP 1, 2 Step Ciara BH SC SF SI 23 (Feat. Miley Cyrus, Wiz Mike Will Made-It PH SP Khalifa And Juicy J) 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind SC 24 Hours At A Time Marshall Tucker Band SG 10 Million People Example SF 24 Hours From Tulsa Gene Pitney MM 10 Minutes Until The Utilities UT 24-7 Kevon Edmonds SC Karaoke Starts (5 Min 24K Magic Bruno Mars MR SF Track) 24's Richgirl & Bun B PH 10 Seconds Jazmine Sullivan PH 25 Miles Edwin Starr SC 10,000 Promises Backstreet Boys BS 25 Minutes To Go Johnny Cash SF 100 Percent Cowboy Jason Meadows PH 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago BS PI SC 100 Years Five For Fighting SC 26 Cents Wilkinsons, The MM SC SF 100% Chance Of Rain Gary Morris SC 26 Miles Four Preps, The SA 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters PI SC 29 Nights Danni Leigh SC 10000 Nights Alphabeat MR SF 29 Palms Robert Plant SC SF 10th Avenue Freeze Out Bruce Springsteen SG 3 Britney Spears CB MR PH 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan BS SC QH SF Len Barry DK 3 AM Matchbox 20 MM SC 1-2-3 Redlight 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

I) Fifteenth Supplemental Debt Resolution for Financing

RESOLUTION of the 170093 DALLAS AREA RAPID TRANSIT BOARD (Executive Committee) RESOLUTION Approval of: I) Fifteenth Supplemental Debt Resolution for Financing Through the Issuance of Senior Lien Sales Tax Revenue Bonds in Conjunction with 1) a Railroad Rehabilitation and Improvement Financing (RRIF) Program Loan, or 2) a Conventional Revenue Bond Issue, or 3) a Combination of a Conventional Revenue Bond Issue and a RRIF Program Loan for the Cotton Belt Commuter Rail Project; and II) Sixteenth Supplemental Debt Resolution for the Purpose of Financing the Second Central Business District (CBD) Light Rail Alignment Project (D2 Subway) WHEREAS, on January 23, 2001, the Board approved the Master Debt Resolution (Resolution No. 010014) and the First Supplemental Debt Resolution authorizing $500 million in DART Commercial Paper Notes, Series 2001 (Resolution No. 010015); and WHEREAS, following Board approval of the Master Debt Resolution and the First Supplemental Debt Resolution, the Board, over a period of time, subsequently approved Supplemental Debt Resolutions Two through Fourteen which authorized the issuance of Revenue Bonds and Commercial Paper Notes to finance the acquisition of capital assets and refund existing debt; and WHEREAS, DART has provided preliminary information to the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) Build America Bureau in support of a $908 million loan for the Cotton Belt commuter rail project through the RRIF Program administered by the Federal Railroad Administration which is authorized to provide direct loans -

American Songwriter – Behind the Song: “Sister Golden Hair”

March 26, 2020 Link to article: https://americansongwriter.com/behind-the-song-sister-golden-hair/ Behind the Song: “Sister Golden Hair” by America Paul Zollo March 26, 2020 America’s Gerry Beckley on the origins of this classic song, and on making the record with the legendary Beatles team of George Martin and Geoff Emerick Because of the Coronavirus and social restrictions here in L.A. and elsewhere at this moment, all new interviews we’re conducting for American Songwriter are being done over the phone. We spoke to Gerry Beckley, who along with Dewey Bunell, separately wrote songs for their band America. Dewey wrote their first #1 hit, the cryptic classic “Horse With No Name” (the origins of which Dewey discusses with us in an upcoming piece). And Gerry wrote their second #1 hit, “Sister Golden Hair,” the main subject of our conversation on this day. Gerry spoke to us from his home in Venice – the California one – near the beach, on the dark morning of March 25, 2020. It was dark both physically and emotionally, because of this crisis, which has been exponentially expanding in many directions every day. The awful news had just come in the night before that Jackson Browne (an old friend of Gerry’s and one who figures into this story), had tested positive for the virus. What was already terrible and frightening had gotten worse, and now was way too close to home. So before getting to a discussion of the song and other musical topics, we spoke about Jackson, and also about how Gerry and his family had been coping with the crisis. -

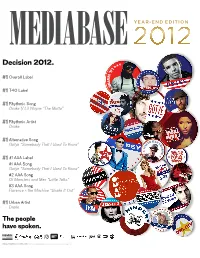

Decision 2012

YEAR-END EDITION MEDIABASE 2012 Decision 2012. #1 Overall Label #1 T40 Label #1 Rhythmic Song Drake f/ Lil Wayne “The Motto” #1 Rhythmic Artist Drake Alternative Song #1 HAW ER T Gotye “Somebody That I Used To Know” Y H A O M R N H E H #1 #1 AAA Label #1 AAA Song Gotye “Somebody That I Used To Know” #2 AAA Song Of Monsters and Men “Little Talks” #3 AAA Song Florence + the Machine “Shake It Out” #1 Urban Artist Drake The people have spoken. www.republicrecords.com c 2012 Universal Republic Records, a Division of UMG Recordings, Inc. REPUBLIC LANDS TOP SPOT OVERALL Republic Top 40 Champ Island Def Jam Takes Rhythmic & Urban Republic t o o k t h e t o p s p o t f o r t h e 2 0 1 2 c h a r t y e a r, w h i c h w e n t f r o m N o v e m b e r 2 0 , 2 0 1 1 - N o v e m b e r 17, 2012. The label was also #1 at Top 40 and Triple A, while finishing #2 at Rhythmic, #3 at Urban, and #4 at AC. Their overall share was 13.5%. Leading the way for Republic was newcomer Gotye, who had one of the year’s biggest hits with “Somebody That I Used To Know.” A big year from Drake and Nicki Minaj also contributed to the label’s success, as well as strong performances for Florence + The Machine, Volbeat, and Of Monsters And Men to name a few. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

The Resolution of Conflict in the Fiction of D. H. Lawrence

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 6-1941 The resolution of conflict in the fiction of. D H. Lawrence. William Sterett Bowmer University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Modern Literature Commons Recommended Citation Bowmer, William Sterett, "The resolution of conflict in the fiction of. D H. Lawrence." (1941). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1688. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/1688 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RESOLUTION OF CONFLICT IN THE FICTION OF D. H. LAWRENCE A Thesis Presented to r the Faculty of the Department of English University of Louisville l ( In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Xas ter of Arts by William Sterett Bowmer June 1941 II " r TABLE OF CONTENTS PART PAGE I. INTRODUCTION • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • ii II. THE RESOLUTIONS OF CONFLICT A. Major Fiction • • • • • • • • • • • • 1 B. Minor Fiction • • • • • • • • • • • • 49 C. The Plays • • • • • • • • • • •••• 59 III. CRITIQUE A. Foreword • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 62 B. The Question of Sexuality •••••• 68 C. Materialism or Not • • • • • • • • • 91 D. Orthodox and Unorthodox Religiosity. 103 E. Art and The Artist • • • • • • • • • 107 F. Loneliness, The Masses, and World Weariness • • • • • • • • • • • • • 112 G. -

Resolution No. 2013-851

RESOLUTION NO. 2013-851 A RESOLUTION TO ADOPT THE RALEIGH STREET DESIGN MANUAL AND REPEAL THE STREETS, SIDEWALKS AND DRIVEWAY ACCESS HANDBOOK WHEREAS, the Raleigh Street Design Manual is an adjunct to the recently adopted Unified Development Ordinance; and WHEREAS, the Manual provides technical specifications used in construction of public improvements; and WHEREAS, many of the technical specifications are engineering based standards that are not appropriate for inclusion in the Unified Development Ordinance; and WHEREAS, the Manual will replace the existing Streets, Sidewalks and Driveway Access Handbook; and WHEREAS, these enhancements were reviewed and discussed with public input. NOW, THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED BY THE CITY COUNCIL OF RALEIGH, NORTH CAROLINA: 1. The Raleigh Street Design Manual dated November 6, 2013 together with the Planning Commission recommendations dated August 13, 2013 contained in certified recommendation number CR-11547, are hereby adopted. 2. The Raleigh Street Design Manual shall be effective five days after the adoption of this resolution. 3. The Streets, Sidewalk and Driveway Access Handbook is hereby repealed coincident with the adoption of the Raleigh Street Design Manual. 4. The Raleigh Street Design Manual is incorporated by the Unified Development Ordinance, Part 10A of the City Code. 5. Except as otherwise authorized in this section, changes to the Raleigh Street Design Manual shall be approved by the City Council after a public hearing. The following changes may be made by staff without need for a City Council public hearing: a. Technical corrections to illustrations where standards are not altered; b. Correction of typographical errors, erroneous information or the addition of or alteration to references to external forms, applications or other governmental information; c. -

Karaoke with a Message – August 16, 2019 – 8:30PM

Another Protest Song: Karaoke with a Message – August 16, 2019 – 8:30PM a project of Angel Nevarez and Valerie Tevere for SOMA Summer 2019 at La Morenita Canta Bar (Puente de la Morena 50, 11870 Ciudad de México, MX) karaoke provided by La Morenita Canta Bar songbook edited by Angel Nevarez and Valerie Tevere ( ) 18840 (Ghost) Riders In The Sky Johnny Cash 10274 (I Am Not A) Robot Marina & Diamonds 00005 (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 17636 (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 15910 (I Want To) Thank You Freddie Jackson 05545 (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees 06305 (It's) A Beautiful Mornin' Rascals 19116 (Just Like) Starting Over John Lennon 15128 (Keep Feeling) Fascination Human League 04132 (Reach Up For The) Sunrise Duran Duran 05241 (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay Otis Redding 17305 (Taking My) Life Away Default 15437 (Who Says) You Can't Have It All Alan Jackson # 07630 18 'til I Die Bryan Adams 20759 1994 Jason Aldean 03370 1999 Prince 07147 2 Legit 2 Quit MC Hammer 18961 21 Guns Green Day 004-m 21st Century Digital Boy Bad Religion 08057 21 Questions 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 00714 24 Hours At A Time Marshall Tucker Band 01379 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 14375 3 Strange Days School Of Fish 08711 4 Minutes Madonna 08867 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin Timberlake 09981 4 Minutes Avant 18883 5 Miles To Empty Brownstone 13317 500 Miles Peter Paul & Mary 00082 59th Street Bridge Song Simon & Garfunkel 00384 9 To 5 Dolly Parton 08937 99 Luftballons Nena 03637 99 Problems Jay-Z 03855 99 Red Balloons Nena 22405 1-800-273-8255 -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Crush Garbage 1990 (French) Leloup (Can't Stop) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue 1994 Jason Aldean (Ghost) Riders In The Sky The Outlaws 1999 Prince (I Called Her) Tennessee Tim Dugger 1999 Prince And Revolution (I Just Want It) To Be Over Keyshia Cole 1999 Wilkinsons (If You're Not In It For Shania Twain 2 Become 1 The Spice Girls Love) I'm Outta Here 2 Faced Louise (It's Been You) Right Down Gerry Rafferty 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue The Line 2 On (Explicit) Tinashe And Schoolboy Q (Sitting On The) Dock Of Otis Redding 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc The Bay 20 Years And Two Lee Ann Womack (You're Love Has Lifted Rita Coolidge Husbands Ago Me) Higher 2000 Man Kiss 07 Nov Beyonce 21 Guns Green Day 1 2 3 4 Plain White T's 21 Questions 50 Cent And Nate Dogg 1 2 3 O Leary Des O' Connor 21st Century Breakdown Green Day 1 2 Step Ciara And Missy Elliott 21st Century Girl Willow Smith 1 2 Step Remix Force Md's 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 1 Thing Amerie 22 Lily Allen 1, 2 Step Ciara 22 Taylor Swift 1, 2, 3, 4 Feist 22 (Twenty Two) Taylor Swift 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 22 Steps Damien Leith 10 Million People Example 23 Mike Will Made-It, Miley 10 Seconds Jazmine Sullivan Cyrus, Wiz Khalifa And 100 Years Five For Fighting Juicy J 100 Years From Now Huey Lewis And The News 24 Jem 100% Cowboy Jason Meadows 24 Hour Party People Happy Mondays 1000 Stars Natalie Bassingthwaighte 24 Hours At A Time The Marshall Tucker Band 10000 Nights Alphabeat 24 Hours From Tulsa Gene Pitney 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan 24 Hours From You Next Of Kin 1-2-3 Len Berry 2-4-6-8 Motorway Tom Robinson Band 1234 Sumptin' New Coolio 24-7 Kevon Edmonds 15 Minutes Rodney Atkins 25 Miles Edwin Starr 15 Minutes Of Shame Kristy Lee Cook 25 Minutes To Go Johnny Cash 16th Avenue Lacy J Dalton 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 18 And Life Skid Row 29 Nights Danni Leigh 18 Days Saving Abel 3 Britney Spears 18 Til I Die Bryan Adams 3 A.M. -

Communication the Adjutant General, the Veterans Of

115th Congress, 1st Session – – – – – – – – – – – – – House Document 115–44 THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE 117TH NATIONAL CON- VENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES COMMUNICATION FROM THE ADJUTANT GENERAL, THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES TRANSMITTING THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE 117TH NATIONAL CONVENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES, HELD IN CHARLOTTE, NORTH CAROLINA, JULY 24–27, 2016, PUR- SUANT TO 44 U.S.C. 1332; (PUBLIC LAW 90–620 (AS AMENDED BY PUBLIC LAW 105–225, SEC. 3); (112 STAT. 1498) MAY 25, 2017.—Referred to the Committee on Veterans’ Affairs and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 25–632 WASHINGTON : 2017 U.S. CODE, TITLE 44, SECTION 1332 NATIONAL ENCAMPMENTS OF VETERANS’ ORGANIZATIONS; PROCEEDINGS PRINTED ANNUALLY FOR CONGRESS The proceedings of the national encampments of the United Spanish War Veterans, the Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States, the American Legion, the Military Order of the Purple Heart, the Veterans of World War I of the United States, Incorporated, the Disabled American Veterans, and the AMVETS (American Veterans of World War II), respectively, shall be printed annually, with accompanying illustrations, as separate House documents of the session of the Congress to which they may be submitted. [Approved October 2, 1968.] II LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI May, 2017 Honorable Paul Ryan The Speaker U. S. House of Representatives Washington, D.C. 20515 Dear Mr. Speaker: In conformance with the provisions of Public Law No. 620, 90th Congress, approved October 22, 1968, I am transmitting to you herewith the proceedings of the 117th National Convention of the Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States, held in Charlotte, North Carolina, July 24-27, 2016, which is submitted for printing as a House document. -

Eminem the Complete Guide

Eminem The Complete Guide PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Wed, 01 Feb 2012 13:41:34 UTC Contents Articles Overview 1 Eminem 1 Eminem discography 28 Eminem production discography 57 List of awards and nominations received by Eminem 70 Studio albums 87 Infinite 87 The Slim Shady LP 89 The Marshall Mathers LP 94 The Eminem Show 107 Encore 118 Relapse 127 Recovery 145 Compilation albums 162 Music from and Inspired by the Motion Picture 8 Mile 162 Curtain Call: The Hits 167 Eminem Presents: The Re-Up 174 Miscellaneous releases 180 The Slim Shady EP 180 Straight from the Lab 182 The Singles 184 Hell: The Sequel 188 Singles 197 "Just Don't Give a Fuck" 197 "My Name Is" 199 "Guilty Conscience" 203 "Nuttin' to Do" 207 "The Real Slim Shady" 209 "The Way I Am" 217 "Stan" 221 "Without Me" 228 "Cleanin' Out My Closet" 234 "Lose Yourself" 239 "Superman" 248 "Sing for the Moment" 250 "Business" 253 "Just Lose It" 256 "Encore" 261 "Like Toy Soldiers" 264 "Mockingbird" 268 "Ass Like That" 271 "When I'm Gone" 273 "Shake That" 277 "You Don't Know" 280 "Crack a Bottle" 283 "We Made You" 288 "3 a.m." 293 "Old Time's Sake" 297 "Beautiful" 299 "Hell Breaks Loose" 304 "Elevator" 306 "Not Afraid" 308 "Love the Way You Lie" 324 "No Love" 348 "Fast Lane" 356 "Lighters" 361 Collaborative songs 371 "Dead Wrong" 371 "Forgot About Dre" 373 "Renegade" 376 "One Day at a Time (Em's Version)" 377 "Welcome 2 Detroit" 379 "Smack That" 381 "Touchdown" 386 "Forever" 388 "Drop the World"