The Work of the Anjuman Samaji Behbood and the Larger Faisalabad Context, Pakistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Faisalabad Chamber of Commerce & Indusrty

THE FAISALABAD CHAMBER OF COMMERCE & INDUSRTY FINAL ASSOCIATE VOTERS FOR THE YEAR 2016-17 Page 1 of 142 1. 2104577-3610 7. 2106048-4897 13. 2103964-3062 3-A TEXTILES A & H CORPORATION A.A ENTERPRISES P-1 SECOND FLOOR SARA TOWER CENTRE OFFICE # 4, 2ND FLOOR ABUTURAB P-27 GALI NO 7 MOHALLAH QASIM MAIN SUSAN ROAD MADINA BUILDING, AMINPUR BAZAR FAISALABAD ABAD,JHANG ROAD, FAISALABAD TOWN,FAISALABAD NTN : 2681221-5 NTN : 2259549-0 NTN : 1324438-8 STN : STN : STN : 08-90-9999-882-82 TEL : 041-8559844,5506962 TEL : 041-2551678 TEL : 041-8723388 CELL: 0300-9656930 CELL: 0300-9652354,0321-7220920 CELL: 0300-8668801 EMAIL :[email protected], rana_248@hotmai EMAIL :[email protected] EMAIL :[email protected] REP : RANA MUNAWAR HUSSAIN REP : HAMID BASHIR REP : AIJAZ AHMAD NIC : 33100-0147581-1 NIC : 33100-4747059-7 NIC : 33100-5628937-9 2. 2106191-5024 8. 2300939-682 14. 2102967-2222 381 INTERNATIONAL A & H ENTERPRISES A.A ENTERPRISES 1ST FLOOR UNION TRADER OPP. SHELL CHEEMA MARKET RAILWAY ROAD SHOP NO 4 AL HAKEEM CENTRE CHTTREE PUMP NEAR GHOUSHALA DIJKOT ROAD FAISALABAD WALA CHOWK JINNAH COLONY FAISALABAD NTN : 2164711-9 FAISALABAD NTN : 2736536-7 STN : 08-01-5900-008-46 NTN : 2316510-3 STN : TEL : 041-2643933 STN : TEL : 041-2626381 CELL: 0300-8666818 TEL : 041-8739180 CELL: 0344-4444381 EMAIL :[email protected] CELL: 0300-8656607 EMAIL :[email protected] REP : MUHAMMAD ASIM EMAIL :[email protected] REP : JAWAD ALI NIC : 33100-1808192-7 REP : ATIF IDREES NIC : 33100-6169762-5 NIC : 33104-2111449-9 3. 2105589-4504 9. -

13100 Faisalabad-I 99 Jul-21

POWER INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY COMPANY FESCO Snaps Accuracy Percentages (General) Jul-21 Sub Sr. Accuracy Division Sub Division Name # % Code 01 13121 Faisalabad City 100 02 13122 Faislabad Civil Line 96 03 13123 Islampura 100 04 13124 Tariqabad 99 05 13125 Sargodha Road 100 06 13126 Haji Abad 99 07 13127 Millat Town 100 08 13128 Muslim Town 100 13120 Civil Line 99 09 13131 Madina Town 98 10 13132 Mansoorabad 100 11 13133 Gatwala 100 12 13134 Manawala 99 13 13138 Jaranwala Road 99 13130 Abdullah Pur 99 14 13141 City S/D FESCO Jrw 100 15 13142 Lhr Rd S/D Jrw 100 16 13143 Fsd Rd S/D Jrw 97 17 13144 Satiana 96 18 13145 Khanuana 100 19 13146 Sarwar Shaheed 99 13140 Jaranwala 99 20 13151 Chak Jhumar-I 98 21 13152 Chak Jhumar-II 99 22 13153 Khurrianwala 100 23 13154 Bandala 99 13150 Chak Jhumra 99 24 13161 Chiniot-I 97 25 13162 Chiniot-II 100 26 13163 Chiniot-III 100 27 13164 Bhawana 100 28 13168 Bukharian 100 13160 Chiniot 99 29 13171 Lalian City 98 30 13172 Lalian Rural 99 31 13173 Chenab Nagar 97 13170 Lalian 98 13100 Faisalabad-I 99 POWER INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY COMPANY FESCO Snaps Accuracy Percentages (General) Jul-21 Sub Sr. Accuracy Division Sub Division Name # % Code 32 13211 Samanabad 100 33 13212 Nazamabad 100 34 13213 Factory Area 100 35 13214 Bakar Mandi 97 36 13215 Jhang Road Fsd 100 37 13216 Thekriwala 99 13210 Nazam Abad 99 38 13221 G. Muhammabad 100 39 13222 Faizabad 100 40 13223 Gulberg 100 41 13224 Razabd 99 42 13225 Narwala Road 99 43 13226 Sadar Bazar 100 44 13227 Rehmat Town 98 45 13228 Madina Abad 100 13220 G.M. -

Iee Report: 220 Kv Dc T. Line from 500 Kv Faisalabad West to 220 Kv Lalian New Substation

Second Power Transmission Enhancement Investment Program (RRP PAK 48078-002) Initial Environmental Examination May 2016 PAK: Proposed Multitranche Financing Facility Second Power Transmission Enhancement Investment Program Prepared by National Transmission and Despatch Company Limited for the Asian Development Bank. Power Transmission Enhancement Investment Programme II TA 8818 (PAK) Initial Environmental Examination 220 kV Double Circuit Transmission Line from 500 kV Faisalabad West Substation to 220 kV Lalian New Substation May 2016 Prepared by National Transmission & Despatch Company Limited (NTDC) for the Asian Development Bank (ADB) The Initial Environmental Examination Report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of the ADB website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgements as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. 2 | P a g e Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 1 1.1. General ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.2. Project Details -

L 118 Official Journal

ISSN 1725-2555 Official Journal L 118 of the European Union Volume 51 English edition Legislation 6 May 2008 Contents I Acts adopted under the EC Treaty/Euratom Treaty whose publication is obligatory REGULATIONS ★ Council Regulation (EC) No 396/2008 of 29 April 2008 amending Regulation (EC) No 397/2004 imposing a definitive anti-dumping duty on imports of cotton-type bed linen originating in Pakistan ........................................................................................... 1 Commission Regulation (EC) No 397/2008 of 5 May 2008 establishing the standard import values for determining the entry price of certain fruit and vegetables ......................................... 8 Commission Regulation (EC) No 398/2008 of 5 May 2008 amending the representative prices and additional duties for the import of certain products in the sugar sector fixed by Regulation (EC) No 1109/2007 for the 2007/08 marketing year ................................................... 10 ★ Commission Regulation (EC) No 399/2008 of 5 May 2008 amending Annex VIII to Regulation (EC) No 1774/2002 of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards requirements for certain processed petfood (1) ..................................................................... 12 ★ Commission Regulation (EC) No 400/2008 of 5 May 2008 amending for the 95th time Council Regulation (EC) No 881/2002 imposing certain specific restrictive measures directed against certain persons and entities associated with Usama bin Laden, the Al-Qaida network and the Taliban ............................................................................................ 14 1 ( ) Text with EEA relevance (Continued overleaf) 2 Acts whose titles are printed in light type are those relating to day-to-day management of agricultural matters, and are generally valid for a limited period. EN The titles of all other acts are printed in bold type and preceded by an asterisk. -

FAISALABAD ELECTRIC SUPPLY COMPANY LIMITED TENDER NOTICE Sealed Tender Is Invited from the Contractor for the Following Work:- Tender No

. FAISALABAD ELECTRIC SUPPLY COMPANY LIMITED TENDER NOTICE Sealed tender is invited from the contractor for the following work:- Tender No. Name of Work Construction of office for SDO (O) Rural Sub Division at 132 KV Grid Station Garh Fateh 162 Tandlianwala. 163 Construction of Deputy Manager (Safety) office at FESCO H/Q Faisalabad. Construction Of (Double Storey) SDO (O) Office Building Tariqabad At Abdullahpur Colony 164 Faisalabad Construction Of (Double Storey) SDO(O) Office Building Manawala Sub Division At 132 Kv 165 Grid Station SPS In Steam Power Station Colony Canal Road Pul 204 Chak Faisalabad Tender can be From the office of Executive Engineer Civil Works Division No.1 FESCO West Canal Road Purchased: Abdullahpur, Faisalabad after fulfilling the conditions mentioned below. Estimated Tender No. 162 Tender No. 163 Tender No. 164 Tender No. 165 Amount: Rs. 5,665,140/- Rs. 2,788,449/- Rs. 7,603,437/- Rs. 7,932,689/- Time of Tender No. 162 Tender No. 163 Tender No. 164 Tender No. 165 Completion: 180 Days 60 Days 180 Days 180 Days 04% of Estimated Amount in the name of Executive Engineer Civil Works Earnest Money or Bid Security: Division No.1 FESCO, Faisalabad. Tender Fee: Rupees Rs.2000/- (Two Thousand Only) Non-Refundable Date of Issuing of Tender: Up to 28/07/2021 during working Hours. Date of Receiving of Tender: 29/07/2021 upto 11:30 Hours. Date of Opening of Tender: 29/07/2021 at 12:00 Hours. In the office of Executive Engineer Civil Works Division No.1 FESCO West Place of Opening of Tender: Canal Road Abdullahpur, Faisalabad Tender will be issued to the contractors on the production of following documents in original. -

Performance Evaluation Report of NTDC & K-Electric 2018-19

NATIONAL ELECTRIC POWER - REGULATORY AUTHORTY 2018-19 Performance Evaluation Report NTDC & K-Electric Contents 0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................... ES-1 1 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 REPORTING REQUIREMENT .................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 COMPLIANCE ......................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2.1 Rule 7 of PSTR 2005 (System Voltage) ....................................................................................... 1 1.2.2 Rule 8 of PSTR 2005 (System Frequency) .................................................................................. 1 2 BRIEF ABOUT NTDC ................................................................................................................................ 2 2.1 LICENCE ................................................................................................................................................ 2 2.2 TRANSMISSION NETWORK .................................................................................................................... 2 2.3 PERFORMANCE AT A GLANCE ............................................................................................................... -

LAHORE-Ren98c.Pdf

Renewal List S/NO REN# / NAME FATHER'S NAME PRESENT ADDRESS DATE OF ACADEMIC REN DATE BIRTH QUALIFICATION 1 21233 MUHAMMAD M.YOUSAF H#56, ST#2, SIDIQUE COLONY RAVIROAD, 3/1/1960 MATRIC 10/07/2014 RAMZAN LAHORE, PUNJAB 2 26781 MUHAMMAD MUHAMMAD H/NO. 30, ST.NO. 6 MADNI ROAD MUSTAFA 10-1-1983 MATRIC 11/07/2014 ASHFAQ HAMZA IQBAL ABAD LAHORE , LAHORE, PUNJAB 3 29583 MUHAMMAD SHEIKH KHALID AL-SHEIKH GENERAL STORE GUNJ BUKHSH 26-7-1974 MATRIC 12/07/2014 NADEEM SHEIKH AHMAD PARK NEAR FUJI GAREYA STOP , LAHORE, PUNJAB 4 25380 ZULFIQAR ALI MUHAMMAD H/NO. 5-B ST, NO. 2 MADINA STREET MOH, 10-2-1957 FA 13/07/2014 HUSSAIN MUSLIM GUNJ KACHOO PURA CHAH MIRAN , LAHORE, PUNJAB 5 21277 GHULAM SARWAR MUHAMMAD YASIN H/NO.27,GALI NO.4,SINGH PURA 18/10/1954 F.A 13/07/2014 BAGHBANPURA., LAHORE, PUNJAB 6 36054 AISHA ABDUL ABDUL QUYYAM H/NO. 37 ST NO. 31 KOT KHAWAJA SAEED 19-12- BA 13/7/2014 QUYYAM FAZAL PURA LAHORE , LAHORE, PUNJAB 1979 7 21327 MUNAWAR MUHAMMAD LATIF HOWAL SHAFI LADIES CLINICNISHTER TOWN 11/8/1952 MATRIC 13/07/2014 SULTANA DROGH WALA, LAHORE, PUNJAB 8 29370 MUHAMMAD AMIN MUHAMMAD BILAL TAION BHADIA ROAD, LAHORE, PUNJAB 25-3-1966 MATRIC 13/07/2014 SADIQ 9 29077 MUHAMMAD MUHAMMAD ST. NO. 3 NAJAM PARK SHADI PURA BUND 9-8-1983 MATRIC 13/07/2014 ABBAS ATAREE TUFAIL QAREE ROAD LAHORE , LAHORE, PUNJAB 10 26461 MIRZA IJAZ BAIG MIRZA MEHMOOD PST COLONY Q 75-H MULTAN ROAD LHR , 22-2-1961 MA 13/07/2014 BAIG LAHORE, PUNJAB 11 32790 AMATUL JAMEEL ABDUL LATIF H/NO. -

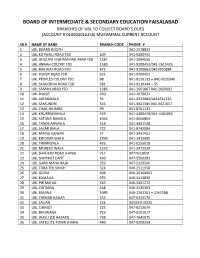

Branches of Ubl to Collect Board's Dues

BOARD OF INTERMEDIATE & SECONDARY EDUCATION FAISALABAD BRANCHES OF UBL TO COLLECT BOARD’S DUES (ACCOUNT # 010901016256) MUKAMMAL CURRENT ACCOUNT SR.# NAME OF BANK BRANCH CODE PHONE. # 1 UBL BOARD BOOTH - 041-2578833 2 UBL KOTWALI ROAD FSD 109 041-9200453 3 UBL GHULAM MUHAMMAD ABAD FSD 1287 041-2694655 4 UBL JINNAH COLONY FSD 1580 041-9200452/041-2615425 5 UBL RAILWAY ROAD FSD 472 041-9200662/0419200884 6 UBL DIJKOT ROAD FSD 531 041-9200451 7 UBL PEOPLES COLONY FSD 98 041-9220133 – 041-9220346 8 UBL SARGODHA ROAD FSD 581 041-9210344 – 35 9 UBL SAMAN ABAD FSD 1286 041-2661867 041-2660092 10 UBL DIJKOT 260 041-2670031 11 UBL JARANWALA 36 041-4312983/0414311126 12 UBL SAMUNDRI 326 041-3421585 041-3421657 13 UBL CHAK JHUMRA 99 041-8761131 14 UBL KHURRIANWALA 429 041-4360429/041-4364050 15 UBL SATANA BANGLA 1066 041-4600804 16 UBL TANDLIANWALA 518 041-3441548 17 UBL SALAR WALA 722 041-8742084 18 UBL MAMU KANJAN 37 041-3431452 19 UBL KHIDDAR WALA 1590 041-3413005 20 UBL THIKRIWALA 433 041-0255018 21 UBL MUREED WALA 1332 041-3472529 22 UBL SHAHEED ROAD JHANG 217 0477613829 23 UBL SHORKOT CANT 430 047-5500281 24 UBL GARH MAHA RAJA 359 047-5320506 25 UBL TOBA TEK SINGH 324 046-2511958 26 UBL GOJRA 404 046-35160062 27 UBL KAMALIA 970 046-3413830 28 UBL PIR MAHAL 545 046-3361272 29 UBL CHITIANA 668 046-2545363 30 UBL RAJANA 1093 046-2262201 – 2261588 31 UBL CHENAB NAGAR 153 047-6334576 32 UBL LALIAN 154 04533-610225 33 UBL CHINIOT 225 047-6213676 34 UBL BHOWANA 726 047-6201017 35 UBL WASU (18 HAZARI) 738 047-7645075 36 UBL SATELLITE TOWN JHANG 440 047-9200254 BOARD OF INTERMEDIATE & SECONDARY EDUCATION FAISALABAD BRANCHES OF MCB TO COLLECT BOARD’S DUES (ACCOUNT # (0485923691000100) PK 365 GOLD SR.# NAME OF BANK BRANCH CODE PHONE. -

Faisalabad Electric Supply Company Limited

P/A FESCO Faisalabad Electric Supply Company Limited 0 ai OFFICE OF THE -‹ Tel # 041-9220576 cn Tel # 041-9220229/153 CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER c-, Fax # 041-9220233 FESCO FAISALABAD ..•,) A rk..) Dated: - 01 — d No. a 7 7 ,2_ /CSD rY1A- V•3 — 1)4) CZ) The Registrar, NEPRA, r:19 2nd Floor, OPF Building, Cvi't /13 7.41 4' — D G-5/2, Islamabad. Subject: POWER PROCUREMENT REQUEST FROM SHAKRGANJ MILLS LTD TOBA ROAD JHANG UNDER NEPRA'S INTERIM POWER PROCUREMENT REGULATION-2005 Reference: S.R.O 265(1)/2005 Notification dated 16.03.2005. FESCO is purchasing 07 MW Bio Gas based Power from M/S .11akar Ganj Mills Toba Road Jhang. In compliance of NEPRA's instructions vide letter No.NEPRATRF 100/696-705 dated 27-01-2012 FESCO hereby requests for acquisition of Power t rider IPPR- 2005 (interim power procurement regulation-2005) of NEPRA. The information as per part-II of Power acquisition permission clause-3(3) is as under please: _e 1 rJ6t1 a— 1. a. The firm's capacity is 8.512 MW Gross. b. Type of fuel is Bio Gas. c. 7 MW Power is being purchased for dispersal into the FESCO system being the redundant/surplus Power available with M/S Shakar Ganj Mills (Ltd) Jha d. The FESCO demand of 07 MW is being met through proposed procurement of power. e. The interconnectivity setup of 11KV Voltage is through existing 11KV Sugar Mills Feeder meant for supplying power to sugar mills during non crushing / non power generation period. -

December 2013 405 Al Baraka Bank (Pakistan) Ltd

Appendix IV Scheduled Banks’ Islamic Banking Branches in Pakistan As on 31st December 2013 Al Baraka Bank -Lakhani Centre, I.I.Chundrigar Road Vehari -Nishat Lane No.4, Phase-VI, D.H.A. (Pakistan) Ltd. (108) -Phase-II, D.H.A. -Provincial Trade Centre, Gulshan-e-Iqbal, Askari Bank Ltd. (38) Main University Road Abbottabad -S.I.T.E. Area, Abbottabad Arifwala Chillas Attock Khanewal Faisalabad Badin Gujranwala Bahawalnagar Lahore (16) Hyderabad Bahawalpur -Bank Square Market, Model Town Islamabad Burewala -Block Y, Phase-III, L.C.C.H.S Taxila D.G.Khan -M.M. Alam Road, Gulberg-III, D.I.Khan -Main Boulevard, Allama Iqbal Town Gujrat (2) Daska -Mcleod Road -Opposite UBL, Bhimber Road Fateh Jang -Phase-II, Commercial Area, D.H.A. -Near Municipal Model School, Circular Gojra -Race Course Road, Shadman, Road Jehlum -Block R-1, Johar Town Karachi (8) Kasur -Cavalry Ground -Abdullah Haroon Road Khanpur -Circular Road -Qazi Usman Road, near Lal Masjid Kotri -Civic Centre, Barkat Market, New -Block-L, North Nazimabad Minngora Garden Town -Estate Avenue, S.I.T.E. Okara -Faisal Town -Jami Commercial, Phase-VII Sheikhupura -Hali Road, Gulberg-II -Mehran Hights, KDA Scheme-V -Kabeer Street, Urdu Bazar -CP & Barar Cooperative Housing Faisalabad (2) -Phase-III, D.H.A. Society, Dhoraji -Chiniot Bazar, near Clock Tower -Shadman Colony 1, -KDA Scheme No. 24, Gulshan-e-Iqbal -Faisal Lane, Civil Line Larkana Kohat Jhang Mansehra Lahore (7) Mardan -Faisal Town, Peco Road Gujranwala (2) Mirpur (AK) -M.A. Johar Town, -Anwar Industrial Complex, G.T Road Mirpurkhas -Block Y, Phase-III, D.H.A. -

X-Ray Facilities with License Valid Upto 30-06-2020

X-ray Facilities with License Valid upto 30-06-2020 Sr. No. Name of Facility Address of Facility District Faisalabad DHQ Hospital Faisalabad 1571. Social Security Faisalabad Road, Jaranwala, District Faisalabad 1572. Hospital Saahil Hospital 1-Sheikhupura Road, Faisalabad 1573. Khadija Mahmood Sargodha Road, Faisalabad 1574. Trust Hospital Chiniot Hospital 209-Jinnah Colony, Faisalabad 1575. Jinnah X-ray Opposite DHQ Hospital, Faisalabad 1576. Dr. Muhammad 342-B, Peoples Coloney No.1, Satiana Road, Faisalabad 1577. Yaqoob Clinic Dr. Muhammad Shahi Chowk, Ghulam Muhammadabad, Faisalabad 1578. Saeed Clinic Rehman Clinical Lab 158-B, Gulistan Colony, Millat Road, Faisalabad 1579. & X-ray Center Mubarak X-ray 576-B, Peoples Colony, Satiana Road, Faisalabad 1580. Centre Mubarak Medical 172-B Gulistan Colony No. 2, Faisalabad 1581. Centre National X-rays & Chowk Akbarabad, Near Allied Hospital, Jail Road, 1582. Ultrasound Faisalabad Nawaz Medicare 62-C, Model Town, Jail Road, Faisalabad 1583. Hospital Rizvi Ultrasound & 547-A, Jinnah Colony, Chatri Wali Ground, Faisalabad 1584. X-ray Clinic Anmol Hospital Rehmania Town, Rehmania Road, Faisalabad 1585. X-ray Facilities with License Valid upto 30-06-2020 Sr. No. Name of Facility Address of Facility West Canal Road, WAPDA Colony, Near Abdullah Pur, WAPDA Hospital 1586. Faisalabad 168-P, Zubair Colony, Jaranwala Road, Dhudiwala, Yasin Hospital 1587. Faisalabad Rehman Hospital Chak No. 66/JB Dhandra, Jhang Road, Faisalabad 1588. The Distt: T.B and Circular Road, Faisalabad 1589. Chest Hospital Mian Muhammad 126-Sargodha Road, Near Bus Stand, Faisalabad 1590. Trust Hospital Faisal Hospital 673-A, Peoples Colony No. 1, Faisalabad 1591. Asghar Clinic Main Bazar, Khurrianwala, District Faisalabad 1592. -

Faisalabad - Consolidated ADP 2012-13

CDG Faisalabad - Consolidated ADP 2012-13 Consolidated Annual Development Programme 2012 -13 Faisalabad (City District Government, WASA and FDA 1 CDG Faisalabad - Consolidated ADP 2012-13 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................... 5 Preface .................................................................................................................................................... 7 Consolidated ADP 2012-13 Faisalabad ................................................................................................... 9 Faisalabad – Summary of Consolidated Annual Development Programme 2012-13-By Entity ....... 11 Faisalabad – Summary of Consolidated Annual Development Programme 2012-13-By Sector ...... 14 Faisalabad – Summary of Consolidated Annual Development Programme 2012-13-By Category .. 16 Faisalabad – Summary of Consolidated Annual Development Programme 2012-13- By Commencement Period .................................................................................................................... 18 City District Government, Faisalabad ................................................................................................... 21 Summary of Annual Development Programme 2012-13 ................................................................. 23 Annual Development Programme 2012-13 - by Category ................................................................ 25 Annual Development Programme 2012-13