Bad Boy by Walter Dean Myers.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STARS Half-Virgin

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2011 Half-virgin Alexander Gregory Pollack University of Central Florida Part of the Creative Writing Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Pollack, Alexander Gregory, "Half-virgin" (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 1951. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/1951 HALF-VIRGIN by ALEXANDER GREGORY POLLACK B.A. Emory University, 2007 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in the Department of Creative Writing in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, FL Spring Term 2011 © 2011 Alexander Gregory Pollack ii ABSTRACT POLLACK, ALEX. Half-Virgin. (Under the direction of Jocelyn Bartkevicius) Half-Virgin is a cross-genre collection of essays, short stories, and poems about the humor, pain, and occasional glory of journeying into adulthood but not quite getting there. The works in this collection seek to create a definition of a term, “half-virgin,” that I coined in the process of writing this thesis. Among the possibilities explored are: an individual who embarks upon sexual activity for the first time and does not achieve orgasm; an individual who has reached orgasm through consensual sexual activity, but has remained uncertain about what he or she is doing; and the curious sensation of being half-child, half-adult. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

2News Summer 05 Catalog

SAV THE BEST IN COMICS & E LEGO ® PUBLICATIONS! W 15 HEN % 1994 --2013 Y ORD OU ON ER LINE FALL 2013 ! AMERICAN COMIC BOOK CHRONICLES: The 1950 s BILL SCHELLY tackles comics of the Atomic Era of Marilyn Monroe and Elvis Presley: EC’s TALES OF THE CRYPT, MAD, CARL BARKS ’ Donald Duck and Uncle Scrooge, re-tooling the FLASH in Showcase #4, return of Timely’s CAPTAIN AMERICA, HUMAN TORCH and SUB-MARINER , FREDRIC WERTHAM ’s anti-comics campaign, and more! Ships August 2013 Ambitious new series of FULL- (240-page FULL-COLOR HARDCOVER ) $40.95 COLOR HARDCOVERS (Digital Edition) $12.95 • ISBN: 9781605490540 documenting each 1965-69 decade of comic JOHN WELLS covers the transformation of MARVEL book history! COMICS into a pop phenomenon, Wally Wood’s TOWER COMICS , CHARLTON ’s Action Heroes, the BATMAN TV SHOW , Roy Thomas, Neal Adams, and Denny O’Neil lead - ing a youth wave in comics, GOLD KEY digests, the Archies and Josie & the Pussycats, and more! Ships March 2014 (224-page FULL-COLOR HARDCOVER ) $39.95 (Digital Edition) $11.95 • ISBN: 9781605490557 The 1970s ALSO AVAILABLE NOW: JASON SACKS & KEITH DALLAS detail the emerging Bronze Age of comics: Relevance with Denny O’Neil and Neal Adams’s GREEN 1960-64: (224-pages) $39.95 • (Digital Edition) $11.95 • ISBN: 978-1-60549-045-8 LANTERN , Jack Kirby’s FOURTH WORLD saga, Comics Code revisions that opens the floodgates for monsters and the supernatural, 1980s: (288-pages) $41.95 • (Digital Edition) $13.95 • ISBN: 978-1-60549-046-5 Jenette Kahn’s arrival at DC and the subsequent DC IMPLOSION , the coming of Jim Shooter and the DIRECT MARKET , and more! COMING SOON: 1940-44, 1945-49 and 1990s (240-page FULL-COLOR HARDCOVER ) $40.95 • (Digital Edition) $12.95 • ISBN: 9781605490564 • Ships July 2014 Our newest mag: Comic Book Creator! ™ A TwoMorrows Publication No. -

First-Run Smoking Presentations in U.S. Movies 1999-2006

First-Run Smoking Presentations in U.S. Movies 1999-2006 Jonathan R. Polansky Stanton Glantz, PhD CENTER FOR TOBAccO CONTROL RESEARCH AND EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN FRANCISCO SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94143 April 2007 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Smoking among American adults fell by half between 1950 and 2002, yet smoking on U.S. movie screens reached historic heights in 2002, topping levels observed a half century earlier.1 Tobacco’s comeback in movies has serious public health implications, because smoking on screen stimulates adolescents to start smoking,2,3 accounting for an estimated 52% of adolescent smoking initiation. Equally important, researchers have observed a dose-response relationship between teens’ exposure to on-screen smoking and smoking initiation: the greater teens’ exposure to smoking in movies, the more likely they are to start smoking. Conversely, if their exposure to smoking in movies were reduced, proportionately fewer teens would likely start smoking. To track smoking trends at the movies, previous analyses have studied the U.S. motion picture industry’s top-grossing films with the heaviest advertising support, deepest audience penetration, and highest box office earnings.4,5 This report is unique in examining the U.S. movie industry’s total output, and also in identifying smoking movies, tobacco incidents, and tobacco impressions with the companies that produced and/or distributed the films — and with their parent corporations, which claim responsibility for tobacco content choices. Examining Hollywood’s product line-up, before and after the public voted at the box office, sheds light on individual studios’ content decisions and industry-wide production patterns amenable to policy reform. -

Noble Causes Volume 7: Powerless Pdf, Epub, Ebook

NOBLE CAUSES VOLUME 7: POWERLESS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jay Faerber | 184 pages | 23 Oct 2007 | Image Comics | 9781582408484 | English | Fullerton, United States Noble Causes Volume 7: Powerless PDF Book Meanwhile, Emelia must endure her marriage to the unctuous George Rathbone, finally witnessing first-hand the freaky practices of the JonahKin. A cross-country journey. In the world where Magic rules, the last four clans of witches meet on the summer solstice for the Rite of Ascendency ceremony. She begins to wonder about her life that could have been. This edit will also create new pages on Comic Vine for: Beware, you are proposing to add brand new pages to the wiki along with your edits. Add to cart Very Good. To make squares disappear and save space for other squares you have to assemble English words left, right, up, down from the falling squares. Cancel Insert. Steven Dockerty escapes from the mental institution where he was being kept and heads straight for Noble Manor. And will Kuo's hand be forced if Takeru does become a demon? When Zephyr discovers that Krennick hires prostitutes to impersonate her, she becomes disgusted and tells Krennick to stay away from her. See if you can get into the grid Hall of Fame! Originally released as part of the first McFarlane's Monsters action figures, these fan-favorite creatures of the night are a must-have for all horror fans. Armed with a yo-yo and a slightly left-of-center attitude, Frank Einstein is Snap City's most impressive masked crime fighter. Disable this feature for this session. -

| | Reapportionment Vote in House

6 THE EYENTXH STAR. TYASHTXfiTOy. P. C, SATURDAY. JANUARY TO. WW. [THE EVENING STAR ? ferences and seiztng an opportunity be- ha* perfected a tube which, through a set with perils. He has yet to conclude color change of its content, unerringly THE LIBRARY TABLE With Sunday Morning Edition. -1 I ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS | his dealings with the Shlnwarls, who indicate* the presence of ga*. That I THIS AND THAT I WASHINGTON, C. are still on the road of insurgency, but will supplant the l D. science feathered i By th« Booklovtr J. HASKIN. Kabul reports confidence that he will songsters in is almost BY FREDERIC | . 1929 > future conflicts SATURDAY. .January 19, effect an adjustment with them. certain. BY CHARLES E. TRACER'ELL. Augustine Birrell says in his “Obiter. public Instruction, reports that it . Afghanistan's new king will not be Doubtless it la better so. The soldier Stop a minute and think about this of , THEODORE W. NOYES... .Editor They are all Dicta,” “History is a pageant and not fact: You can aak our Information is sll4. At the beginning of this cen- known as Bacha Sagao, which Is not a now seldom uses horse* or rpules, which i There is nothing like getting mad have arisen from them. average salary $24. of their origins, just philosophy.” This dictum would ap- Bureau any question of fact and get the tury the was royal designation. He has, it is stated, once played ao important so , 1 to make one forget minor ills. the finer because a The Star Newspaper Company r and tragic powers of anger, in not as a coward who performs bravely on history well as to the answer back in a personal letter. -

Effects of State-Wide Salary Equity Provisions on Institutional Salary

' . * o :0 '4 41,1,4 MINED! RUDE mt. ID 152,205 .HE 009 800 . JUTHOR Nittin, NaryP. 'Mitts, Johat.D. TITLE: Affects ,of State -Wide Salary Equity Provisions on Xpdtitutionhl Salary Policies: A Regression fAlysis; , , . 111SirrillIZON Plorilla'StatelnAv., TalltlAssee.Laorth Dakiita. Univ., Grand Perks. 11.18 DiT.) 78. , , - 17p. 110T3 % . pRicv NP -10,83 Plus-Postage.' RIpIORS., *College Eacultt; *Contracts; Higher Education; si VrivateColleges***Salary Differentials;.*State . : Action; State.Coileges; State Universities; 'Statistical Analysis; Statistical Data; *teacher' Salaries: Tenure. lb$NTIFIERS. .North Dakota; *Univeetity of Nortb-Dalota . A SBSTRAC2 . 4 . fla A procese cl4 equalization of salariel "has- taken plagAl _in thef*State of forth:Dakota-for higher eddcaticn 4uring' the 1977:78- school year. She stab cf North Dakota suppa*ts eight:instittrtionsof kigherleducation: tmoagiveisities, four state colleges, and tvb . two-.y partinstitutions. fhe equalization process as it effected the ,decid4.oa leaking at the .University 01 North Dakota is docualhted. , -:Table 0are, presented" that report' the results for the 1977-78 contracted., salary and the 1977 -78,salary after the equity' adjittaeits. (SPG) ! - :- I 4 ) ************************4****************************** 4,************** * - Reproductions sipplied'by16RS are the best that cab be made - * frothe original document. * *********************4**********************.*************************** , Ai f. 4 4 1 -ewe- teagil I tt-e, ..i_:10 EFFECTS OF STATE-WIDE SALARY EQUITY PROVISIONS ON. (gt-p;,2. _ 10-Is INSTITUTIONAL SALARY POLICIES: A REGRESSION ANALYSIS LiA* 44).;0=0_I ,,_c§f0zaz /. Duz e xi.A0.-0.79, 2 ..0.01, 0 ,Mary P:' Martin and John D. Williams Florida State University University of North Dakota t A process of equalization of sa3aries has taken place in the State Of Ntrth Dakota for.highertducation during the 1977/-78 schoolyear. -

Dead Zone Back to the Beach I Scored! the 250 Greatest

Volume 10, Number 4 Original Music Soundtracks for Movies and Television FAN MADE MONSTER! Elfman Goes Wonky Exclusive interview on Charlie and Corpse Bride, too! Dead Zone Klimek and Heil meet Romero Back to the Beach John Williams’ Jaws at 30 I Scored! Confessions of a fi rst-time fi lm composer The 250 Greatest AFI’s Film Score Nominees New Feature: Composer’s Corner PLUS: Dozens of CD & DVD Reviews $7.95 U.S. • $8.95 Canada �������������������������������������������� ����������������������� ���������������������� contents ���������������������� �������� ����� ��������� �������� ������ ���� ���������������������������� ������������������������� ��������������� �������������������������������������������������� ����� ��� ��������� ����������� ���� ������������ ������������������������������������������������� ����������������������������������������������� ��������������������� �������������������� ���������������������������������������������� ����������� ����������� ���������� �������� ������������������������������� ���������������������������������� ������������������������������������������ ������������������������������������� ����� ������������������������������������������ ��������������������������������������� ������������������������������� �������������������������� ���������� ���������������������������� ��������������������������������� �������������� ��������������������������������������������� ������������������������� �������������������������������������������� ������������������������������ �������������������������� -

Northridge Review

Northridge Review Spring 2013 Acknowledgements The Northridge Review gratefully acknowledges the Associated Students of CSUN and the English Department faculty and staff,Frank De La Santo, Marjie Seagoe, Tonie Mangum, and Marleene Cooksey for all their help. Submission Information The N orthridge Review accepts submissions of fiction, creative nonfiction, poetry, drama, and art throughout the year. The Northridge Review has recently changed the submission process. Manuscripts can be uploaded to the following page: http://thenorthridgereview.submittable.com/submit Submissions should be accompanied by a cover page that includes the writer's name, address, email, and phone number, as well as the titles of the works submitted. The writer's name should not appear on the manu script itself. Printed manuscripts and all other correspondence can still be delivered to the following address: Northridge Review Department of English California State University Northridge 18111 NordhoffSt. Northridge, CA 91330-8248 Staff Chief Editor Faculty Advisor Karlee Johnson Mona Houghton Poetry Editors Fiction Editor ltiola "Stephanie"Jones Olvard Smith Nicole Socala Fiction Board Poetry Board Aliou Amravanti Kashka Mandela Anna Austin Brown-Burke Jasmine Adame Alexandra Johnson KyleLifton Karlee Johnson Marcus Landon Saman Kangarloo Khiem N gu.yen Kristina Kolesnyk Evon Magana Business Manager Rich McGinis Meaghan Gallagher Candice Montgomery Emily Robles Business Board Alexandra Johnson Layout and Design Editor Karlee Johnson A[iou Amravanti Kashka Mandela ltiola "Stephanie" Jones Brown-Burke Saman Kangarloo Layout and Design Board Desktop Publishing Editors Jasmine Adame Marcus Landon Anna Austin Emily Robles Kyle Lifton Evon Magana Desktop Publishing Board Khiem Nguyen KristinaKolesrryk O[vard Smith Rich McGinis Nicole Socala Candice Montgomery Awards The Northridge Review Fiction Award, given annually, recognizes excel lent fiction by a CSUN student published in the Northridge Review. -

Lakeland Overall Score Reports

Lakeland Overall Score Reports Mini (8 yrs. & Under) Solo Recreational Platinum 1st Place 1 547 I Like to Fuss - Dance Dynamix - Leesburg, FL 82.0 Landi Hicks Platinum 1st Place 2 578 Hallelujah Hop - Debbie Cole's School of Dance - Homosassa Springs, FL 81.7 Alyceea Marcic Gold 1st Place 3 352 Constant As the Stars - Showtime Dance Studios - Altamonte Springs, FL 81.2 Shaina Smith Gold 1st Place 4 577 Head Over Heels - Debbie Cole's School of Dance - Homosassa Springs, FL 80.2 Gabrielle Marcic Gold 1st Place 5 106 Opus 1 - Deborah Vinton School of Ballet - Bradenton, FL 79.8 Will Miller Gold 1st Place 6 195 Castle on a cloud - Community Dance Connection - Coco, FL 79.6 Kathryn Meagher Gold 1st Place 7 349 Black Horse and a Cherry Tree - Showtime Dance Studios - Altamonte Springs, FL 79.3 Alexa Adams Competitive Platinum 1st Place 1 303 Some Kind of Wonderful - Deltona Academy of Dance - Deland, FL 84.3 Sydney Bettes Platinum 1st Place 2 780 Little Bitty - Studio 5D - Winter Springs, FL 83.9 Alexandria Navarro Platinum 1st Place 3 335 I've Got the World on a String - Erin's Danceworks - Spring Hill, FL 83.6 Kelcey Morris Platinum 1st Place 4 345 Pink Dancer - Showtime Dance Studios - Altamonte Springs, FL 83.2 Logan Misuraca Gold 1st Place 5 350 Dare You To Move - Showtime Dance Studios - Altamonte Springs, FL 82.5 Ashleigh Hambleton Gold 1st Place 6 253 Shop Around - Jayde Howard's Dance Legacy - Bradenton, FL 82.4 Karyssa Wong Gold 1st Place 7 885 Cruella de Vil - Tammy's Dance Co - , 82.2 Makinsy Wendel Gold 1st Place 8 110 Wish Upon -

Mise En Page 1

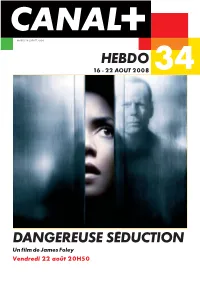

MARDI 29 JUILLET 2008 HEBDO 16 - 22 AOUT 2008 34 DANGEREUSE SÉDUCTION Un film de James Foley Vendredi 22 août 20H50 VOS SOIRÉES SUR ¢ LE BOUQUET PANTONEARGENT 877 + NOIRROCESS P BLACK QUADRI GRIS 40%du DE NOIR +16 NOIR 100% au 22 août 2008 PANTONEARGENT 877 + NOIRROCESS P BLACK QUADRI GRIS 40% DE NOIR + NOIR 100% SAMEDI 16 DIMANCHE 17 LUNDI 18 20H50 HOT FUZZ 20H50 FOOTBALL 20H50 MAFIOSA cinéma ligue 1 LE CLAN S.1 23H00 JOUR DE FOOT 23H00 MIAMI VICE, DEUX série PANTONEARGENT 877 + NOIRROCESS P BLACK QUADRI GRIS 40% DE NOIR + NOIR 100% sport FLICS A MIAMI 22H35 HOT FUZZ cinéma cinéma 20H50 FRAGILE(S) 20H50 BEFORE SUNSET 20H50 ABANDONNÉE cinéma cinéma cinéma 22H30 MICKROCINÉ 22H25 DE L'OMBRE 22H25 APPARENCES courts et créations A LA LUMIÈRE cinéma cinéma 20H45 BEIJING SOIR 20H45 BEIJING SOIR 20†45 BEIJING SOIR 22†05 JEUX OLYMPIQUES 22†05 JEUX OLYMPIQUES 22†05 JEUX OLYMPIQUES BEIJING 2008 BEIJING 2008 BEIJING 2008 20†45 ZORA LA ROUSSE 20†45 ROBIN DES BOIS 20†45 LE MONDE cinéma série DE NARNIA 22†20 LE PETIT POUCET 22†15 HISTORY BOYS cinéma cinéma cinéma 23†00 ON ARRÊTE QUAND ? cinéma 20†50PUR WEEK-END 20†50 HOT FUZZ 20†50 STICK IT cinéma cinéma cinéma 22H15 HOT FUZZ 22H45 LA COMMUNE 22H30 8 HEURES CONO cinéma série magazines et divertissement 34 34 00H00 EN CLAIR 3400H00 EN CRYPTÉ 34 34 ¢ LE BOUQUET MARDI 19 MERCREDI 20 JEUDI 21 VENDREDI 22 20H50 HOLLYWOODLAND 20H50 MA VIE SANS LUI 20H50 STARTER WIFE S.1 20H50 DANGEREUSE cinéma cinéma série SÉDUCTION 22H55 CARTOUCHES 22H40 JE DÉTESTE 22H15 RAINES cinéma GAULOISES LES ENFANTS série 22H35 MI$E A PRIX cinéma DES AUTRES cinéma cinéma 20H50 LOVE (ET SES 20H50 L'ÉCHINE 20H50 LES VACANCES 20H50 ASSASSIN(S) PETITS DÉSASTRES) DU DIABLE DE MR. -

N° Artiste Titre Formatdate Modiftaille 14152 Paul Revere & the Raiders Hungry Kar 2001 42 277 14153 Paul Severs Ik Ben

N° Artiste Titre FormatDate modifTaille 14152 Paul Revere & The Raiders Hungry kar 2001 42 277 14153 Paul Severs Ik Ben Verliefd Op Jou kar 2004 48 860 14154 Paul Simon A Hazy Shade Of Winter kar 1995 18 008 14155 Me And Julio Down By The Schoolyard kar 2001 41 290 14156 You Can Call Me Al kar 1997 83 142 14157 You Can Call Me Al mid 2011 24 148 14158 Paul Stookey I Dig Rock And Roll Music kar 2001 33 078 14159 The Wedding Song kar 2001 24 169 14160 Paul Weller Remember How We Started kar 2000 33 912 14161 Paul Young Come Back And Stay kar 2001 51 343 14162 Every Time You Go Away mid 2011 48 081 14163 Everytime You Go Away (2) kar 1998 50 169 14164 Everytime You Go Away kar 1996 41 586 14165 Hope In A Hopeless World kar 1998 60 548 14166 Love Is In The Air kar 1996 49 410 14167 What Becomes Of The Broken Hearted kar 2001 37 672 14168 Wherever I Lay My Hat (That's My Home) kar 1999 40 481 14169 Paula Abdul Blowing Kisses In The Wind kar 2011 46 676 14170 Blowing Kisses In The Wind mid 2011 42 329 14171 Forever Your Girl mid 2011 30 756 14172 Opposites Attract mid 2011 64 682 14173 Rush Rush mid 2011 26 932 14174 Straight Up kar 1994 21 499 14175 Straight Up mid 2011 17 641 14176 Vibeology mid 2011 86 966 14177 Paula Cole Where Have All The Cowboys Gone kar 1998 50 961 14178 Pavarotti Carreras Domingo You'll Never Walk Alone kar 2000 18 439 14179 PD3 Does Anybody Really Know What Time It Is kar 1998 45 496 14180 Peaches Presidents Of The USA kar 2001 33 268 14181 Pearl Jam Alive mid 2007 71 994 14182 Animal mid 2007 17 607 14183 Better