The Phiri Water Rights Application and Evaluating, Understanding, and Enforcing the South African Constitutional Right to Water

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Constitutional Court of South Africa: Rights Interpretation and Comparative Constitutional Law

THE CONSTITUTIONAL COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA: RIGHTS INTERPRETATION AND COMPARATIVE CONSTITUTIONAL LAW Hoyt Webb- I do hereby swear that I will in my capacity asJudge of the Constitu- tional Court of the Republic of South Africa uphold and protect the Constitution of the Republic and the fundamental rights entrenched therein and in so doing administerjustice to all persons alike with- out fear,favour or prejudice, in accordance with the Constitution and the Law of the Republic. So help me God. The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, Schedule 3 (Oaths of Office and Solemn Affirmations), Act No. 200, 1993. I swear that, asJudge of the ConstitutionalCourt, I will be faithful to the Republic of South Africa, will uphold and protect the Consti- tution and the human rights entrenched in it, and will administer justice to all persons alike withwut fear,favour or prejudice, in ac- cordancewith the Constitution and the Law. So help me God. The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996, Schedule 2 (Oaths and Solemn Affirmations), Act 108 of 1996. I. INTRODUCTION In 1993, South Africa adopted a transitional or interim Constitu- tion (also referred to as the "IC"), enshrining a non-racial, multiparty democracy, based on respect for universal rights.' This uras a monu- mental achievement considering the complex and often horrific his- tory of the Republic and the increasing racial, ethnic and religious tensions worldwide.2 A new society, however, could not be created by Hoyt Webb is an associate at Brown and Wood, LLP in NewYork City and a term member of the Council on Foreign Relations. -

Appointments to South Africa's Constitutional Court Since 1994

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 15 July 2015 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Johnson, Rachel E. (2014) 'Women as a sign of the new? Appointments to the South Africa's Constitutional Court since 1994.', Politics gender., 10 (4). pp. 595-621. Further information on publisher's website: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X14000439 Publisher's copyright statement: c Copyright The Women and Politics Research Section of the American 2014. This paper has been published in a revised form, subsequent to editorial input by Cambridge University Press in 'Politics gender' (10: 4 (2014) 595-621) http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayJournal?jid=PAG Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk Rachel E. Johnson, Politics & Gender, Vol. 10, Issue 4 (2014), pp 595-621. Women as a Sign of the New? Appointments to South Africa’s Constitutional Court since 1994. -

WT/2 Col Template

THEWORLDTODAY.ORG JANUARY 2010 PAGE 16 INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT PRichard Deicker, DIREaCTOR, HUMANcRIGHTS WATeCH’S INTERNATIONAL JUSTICE PROGRAMME, RECENT SPEAKER AT THE CHATHAM HOUSE INTERN &Justice The International Criminal Court believes it is marginalising Sudan’s President Omar al-Bashir following his indictment on charges related to atrocities in Darfur. He decided to pull out of an Islamic summit in Istanbul in November and earlier cancelled plans to visit a number of African states. But the policy of seeking justice in such cases where peace efforts are underway, is deeply controversial. HE THORNY DEBATE OVER WHETHER PURSUING However, an analysis of the details documented in our justice for grave international crimes interferes recent report, Selling Justice Short: Why Accountability with peace negotiations has intensified as Matters for Peace, shows that out-of-hand dismissal of justice the possibility of abusive national leaders often proves shortsighted. We believe that those who want to being tried for such crimes has increased. forgo justice need to consider the facts more carefully, many t In part this is because of the establishment contradict oft-repeated assumptions. Because the of the International Criminal Court (ICC) which is mandated consequences for people at risk are so great, decisions on these to investigate and prosecute war crimes, crimes against important issues need to be fully informed. humanity, and genocide in ongoing conflicts. The call to suspend or ‘sequence’ justice in exchange for a possible end to a conflict has arisen in conjunction with the court’s work HIGH PRICE in Congo, Uganda, and most especially Darfur, with the From the perspective of many victims of atrocities, as well arrest warrant against a sitting head of state, Sudan’s as human rights and international law standards, justice for President Omar al-Bashir. -

Dc/Judges Speak Out?

DC/JUDGES SPEAK OUT? * Richard Goldstone 36th Alfred and Winifred Hoernle Memorial Lecture Delivered in Johannesburg on 10 February 1993 Do Judges Speak Out? MR JUSTICE RICHARD GOLDSTONE SOUTH AFRICAN INSTITUTE OF RACE RELATIONS JOHANNESBURG 1993 Published by the South African Institute of Race Relations Auden House, 68 De Korte Street, Braamfontein, Johannesburg, 2001 South Africa ® South African Institute of Race Relations, 1993 PD8/93 ISBN 0-86982431-7 Members of the media are free to reprint or report information, either in whole or in part, contained in this publication on the strict understanding that the South African Institute of Race Relations is acknowledged. Otherwise, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electrical, mechanical, photocopy, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Printed by Galvin & Sales, Cape Town PREVIOUS HOERNLE LECTURES J H Hoftneyr, Christian principles and race problems (1945) E G Malherbe, Race attitudes and education (1946) I D Macrone, Group conflicts and race prejudice (1947) A W Hoernle, Penal reform and race relations (1948) W M Macmillan, Africa beyond the Union (1949) E H Brookes, We come of age (1950) H J van Eck, Some aspects of the South African industrial revolution (1951) S H Frankel, Some reflections on civilization in Africa (1952) A R R Brown, Outlook for Africa (1953) E Ross, Colour and Christian community (1954) T B Davie, Education and race relations in South Africa (1955) -

1 Frank Michelman Constitutional Court Oral History Project 28Th

Frank Michelman Constitutional Court Oral History Project 28th February 2013 Int This is an interview with Professor Frank Michelman, and it’s the 28th of February 2013. Frank, thank you so much for agreeing to participate in the Constitutional Court Oral History Project, we really appreciate your time. FM I’m very much honoured by your inviting me to participate and I’m happy to do so. Int Thank you. I’ve not had the opportunity to interview you before, and I wondered whether you could talk about early childhood memories, and some of the formative experiences that may have led you down a legal and academic professional trajectory? FM Well, that’s going to be difficult, because…because I didn’t have any notion at all prior to my senior year in college, the year before I entered law school, that I would be going to law school. I hadn’t formed, that I can recall, any plan, hope, ambition, in that direction at all. To the extent that I had any distinct career notion in mind during the years before I wound up going to law school? It would have been an academic career, possibly in the field of history, in which I was moderately interested and which was my concentration in college. I had formed a more or less definite idea of applying to graduate programs in history, and turning myself into a history professor. Probably United States history. United States history, or maybe something along the line of what’s now called the field of ideas, which I was calling intellectual history in those days. -

EASTERN CAPE NARL 2014 (Approved by the Federal Executive)

EASTERN CAPE NARL 2014 (Approved by the Federal Executive) Rank Name 1 Andrew (Andrew Whitfield) 2 Nosimo (Nosimo Balindlela) 3 Kevin (Kevin Mileham) 4 Terri Stander 5 Annette Steyn 6 Annette (Annette Lovemore) 7 Confidential Candidate 8 Yusuf (Yusuf Cassim) 9 Malcolm (Malcolm Figg) 10 Elza (Elizabeth van Lingen) 11 Gustav (Gustav Rautenbach) 12 Ntombenhle (Rulumeni Ntombenhle) 13 Petrus (Petrus Johannes de WET) 14 Bobby Cekisani 15 Advocate Tlali ( Phoka Tlali) EASTERN CAPE PLEG 2014 (Approved by the Federal Executive) Rank Name 1 Athol (Roland Trollip) 2 Vesh (Veliswa Mvenya) 3 Bobby (Robert Stevenson) 4 Edmund (Peter Edmund Van Vuuren) 5 Vicky (Vicky Knoetze) 6 Ross (Ross Purdon) 7 Lionel (Lionel Lindoor) 8 Kobus (Jacobus Petrus Johhanes Botha) 9 Celeste (Celeste Barker) 10 Dorah (Dorah Nokonwaba Matikinca) 11 Karen (Karen Smith) 12 Dacre (Dacre Haddon) 13 John (John Cupido) 14 Goniwe (Thabisa Goniwe Mafanya) 15 Rene (Rene Oosthuizen) 16 Marshall (Marshall Von Buchenroder) 17 Renaldo (Renaldo Gouws) 18 Bev (Beverley-Anne Wood) 19 Danny (Daniel Benson) 20 Zuko (Prince-Phillip Zuko Mandile) 21 Penny (Penelope Phillipa Naidoo) FREE STATE NARL 2014 (as approved by the Federal Executive) Rank Name 1 Patricia (Semakaleng Patricia Kopane) 2 Annelie Lotriet 3 Werner (Werner Horn) 4 David (David Christie Ross) 5 Nomsa (Nomsa Innocencia Tarabella Marchesi) 6 George (George Michalakis) 7 Thobeka (Veronica Ndlebe-September) 8 Darryl (Darryl Worth) 9 Hardie (Benhardus Jacobus Viviers) 10 Sandra (Sandra Botha) 11 CJ (Christian Steyl) 12 Johan (Johannes -

African National Congress NATIONAL to NATIONAL LIST 1. ZUMA Jacob

African National Congress NATIONAL TO NATIONAL LIST 1. ZUMA Jacob Gedleyihlekisa 2. MOTLANTHE Kgalema Petrus 3. MBETE Baleka 4. MANUEL Trevor Andrew 5. MANDELA Nomzamo Winfred 6. DLAMINI-ZUMA Nkosazana 7. RADEBE Jeffery Thamsanqa 8. SISULU Lindiwe Noceba 9. NZIMANDE Bonginkosi Emmanuel 10. PANDOR Grace Naledi Mandisa 11. MBALULA Fikile April 12. NQAKULA Nosiviwe Noluthando 13. SKWEYIYA Zola Sidney Themba 14. ROUTLEDGE Nozizwe Charlotte 15. MTHETHWA Nkosinathi 16. DLAMINI Bathabile Olive 17. JORDAN Zweledinga Pallo 18. MOTSHEKGA Matsie Angelina 19. GIGABA Knowledge Malusi Nkanyezi 20. HOGAN Barbara Anne 21. SHICEKA Sicelo 22. MFEKETO Nomaindiya Cathleen 23. MAKHENKESI Makhenkesi Arnold 24. TSHABALALA- MSIMANG Mantombazana Edmie 25. RAMATHLODI Ngoako Abel 26. MABUDAFHASI Thizwilondi Rejoyce 27. GODOGWANA Enoch 28. HENDRICKS Lindiwe 29. CHARLES Nqakula 30. SHABANGU Susan 31. SEXWALE Tokyo Mosima Gabriel 32. XINGWANA Lulama Marytheresa 33. NYANDA Siphiwe 34. SONJICA Buyelwa Patience 35. NDEBELE Joel Sibusiso 36. YENGENI Lumka Elizabeth 37. CRONIN Jeremy Patrick 38. NKOANA- MASHABANE Maite Emily 39. SISULU Max Vuyisile 40. VAN DER MERWE Susan Comber 41. HOLOMISA Sango Patekile 42. PETERS Elizabeth Dipuo 43. MOTSHEKGA Mathole Serofo 44. ZULU Lindiwe Daphne 45. CHABANE Ohm Collins 46. SIBIYA Noluthando Agatha 47. HANEKOM Derek Andre` 48. BOGOPANE-ZULU Hendrietta Ipeleng 49. MPAHLWA Mandisi Bongani Mabuto 50. TOBIAS Thandi Vivian 51. MOTSOALEDI Pakishe Aaron 52. MOLEWA Bomo Edana Edith 53. PHAAHLA Matume Joseph 54. PULE Dina Deliwe 55. MDLADLANA Membathisi Mphumzi Shepherd 56. DLULANE Beauty Nomvuzo 57. MANAMELA Kgwaridi Buti 58. MOLOI-MOROPA Joyce Clementine 59. EBRAHIM Ebrahim Ismail 60. MAHLANGU-NKABINDE Gwendoline Lindiwe 61. NJIKELANA Sisa James 62. HAJAIJ Fatima 63. -

Gender Audit of the May 2019 South African Elections

BEYOND NUMBERS: GENDER AUDIT OF THE MAY 2019 SOUTH AFRICAN ELECTIONS Photo: Colleen Lowe Morna By Kubi Rama and Colleen Lowe Morna 0 697 0 6907 1 7 2 9 4852 9 4825 649 7 3 7 3 93 85 485 68 485 768485 0 21 0 210 168 01697 016907 127 2 9 4852 9 4825 649 7 3 7 3 93 85 485 68 485 768485 0 21 0 210 168 01697 016907 127 2 9 4852 9 4825 649 7 3 7 3 93 85 485 68 485 768485 0 21 0 210 168 01697 016907 127 2 9 4852 9 4825 649 7 3 7 3 93 85 485 68 485 768485 6 0 21 0 210 18 01697 016907 127 2 9 4852 9 4825 649 7 3 7 3 93 85 485 6 485 76485 0 0 0 6 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 QUOTAS AND PARTY LISTS 4 WOMEN'S PERFORMANCE IN THE ELECTIONS 5 • The National Council of Provinces or upper house 6 • Cabinet 7 • Provincial legislatures 8 • Speakers at national and provincial level 9 WOMEN AS VOTERS 9 • Giving young people a reason to vote 10 BEYOND NUMBERS: GENDER ANALYSIS OF POLITICAL PARTY MANIFESTOS 11 VOICE AND CHOICE? WOMEN EVEN LESS VISIBLE IN THE MEDIA 13 CONCLUSIONS 16 RECOMMENDATIONS 17 List of figures One: Proportion of women in the house of assembly from 1994 to 2019 5 Two: Breakdown of the NCOP by sex 6 Three: Proportion of ministers and deputy ministers by sex 7 Four: Proportion of women and men registered voters in South Africa as at May 2019 9 Five: Topics that received less than 0.2% coverage 14 List of tables One: Women in politics in South Africa, 2004 - 2019 3 Two: Quotas and positioning of women in the party lists 2019 4 Three: Gender audit of provincial legislatures 8 Four: Sex disaggregated data on South African voters by age -

At the Intersection of Neoliberal Development, Scarce Resources, and Human Rights: Enforcing the Right to Water in South Africa Elizabeth A

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College International Studies Honors Projects International Studies Department Spring 5-3-2010 At the intersection of neoliberal development, scarce resources, and human rights: Enforcing the right to water in South Africa Elizabeth A. Larson Macalester College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/intlstudies_honors Part of the African Studies Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, International Law Commons, Nature and Society Relations Commons, Political Economy Commons, and the Water Law Commons Recommended Citation Larson, Elizabeth A., "At the intersection of neoliberal development, scarce resources, and human rights: Enforcing the right to water in South Africa" (2010). International Studies Honors Projects. Paper 10. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/intlstudies_honors/10 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the International Studies Department at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Studies Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. At the intersection of neoliberal development, scarce resources, and human rights: Enforcing the right to water in South Africa Elizabeth A. Larson Honors Thesis Advisor: Professor James von Geldern Department: International Studies Abstract The competing ideals of international human rights and global economic neoliberalism come into conflict when developing countries try to enforce socio- economic rights. This paper explores the intersection of economic globalization and the enforcement of 2 nd generation human rights. The focus of this exploration is the right to water in South Africa, specifically the recent Constitutional Court case Mazibuko v City of Johannesburg . -

New South African Constitution and Ethnic Division, the Stephen Ellmann New York Law School, [email protected]

digitalcommons.nyls.edu Faculty Scholarship Articles & Chapters 1994 New South African Constitution and Ethnic Division, The Stephen Ellmann New York Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/fac_articles_chapters Recommended Citation 26 Colum. Hum. Rts. L. Rev. 5 (1994-1995) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles & Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@NYLS. THE NEW SOUTH AFRICAN CONSTITUTION AND ETHNIC DIVISION by Stephen Ellmann* I. INTRODUCTION In an era of ethnic slaughter in countries from Bosnia to Rwanda, the peril of ethnic division cannot be ignored. Reducing that peril by constitutional means is no simple task, for when ethnic groups pull in different directions a free country can only produce harmony between them by persuading each to honor some claims of the other and to moderate some claims of its own. It will require much more than technical ingenuity in constitution-writing to generate such mutual forbearance. Moreover, constitutional provisions that promote this goal will inevitably do so at a price - namely, the reduction of any single group's ability to work its will through the political process. And that price is likely to be most painful to pay when it entails restraining a group's ability to achieve goals that are just - for example, when it limits the ability of the victims of South African apartheid to redress the profound injustice they have suffered. This Article examines the efforts of the drafters of the new transitional South African Constitution to overcome ethnic division, or alternatively to accommodate it. -

The Thinker Congratulates Dr Roots Everywhere

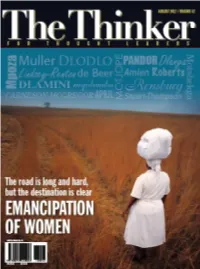

CONTENTS In This Issue 2 Letter from the Editor 6 Contributors to this Edition The Longest Revolution 10 Angie Motshekga Sex for sale: The State as Pimp – Decriminalising Prostitution 14 Zukiswa Mqolomba The Century of the Woman 18 Amanda Mbali Dlamini Celebrating Umkhonto we Sizwe On the Cover: 22 Ayanda Dlodlo The journey is long, but Why forsake Muslim women? there is no turning back... 26 Waheeda Amien © GreatStock / Masterfile The power of thinking women: Transformative action for a kinder 30 world Marthe Muller Young African Women who envision the African future 36 Siki Dlanga Entrepreneurship and innovation to address job creation 30 40 South African Breweries Promoting 21st century South African women from an economic 42 perspective Yazini April Investing in astronomy as a priority platform for research and 46 innovation Naledi Pandor Why is equality between women and men so important? 48 Lynn Carneson McGregor 40 Women in Engineering: What holds us back? 52 Mamosa Motjope South Africa’s women: The Untold Story 56 Jennifer Lindsey-Renton Making rights real for women: Changing conversations about 58 empowerment Ronel Rensburg and Estelle de Beer Adopt-a-River 46 62 Department of Water Affairs Community Health Workers: Changing roles, shifting thinking 64 Melanie Roberts and Nicola Stuart-Thompson South African Foreign Policy: A practitioner’s perspective 68 Petunia Mpoza Creative Lens 70 Poetry by Bridget Pitt Readers' Forum © SAWID, SAB, Department of 72 Woman of the 21st Century by Nozibele Qutu Science and Technology Volume 42 / 2012 1 LETTER FROM THE MaNagiNg EDiTOR am writing the editorial this month looks forward, with a deeply inspiring because we decided that this belief that future generations of black I issue would be written entirely South African women will continue to by women. -

World Economic Forum on Africa

World Economic Forum on Africa List of Participants As of 7 April 2014 Cape Town, South Africa, 8-10 May 2013 Jon Aarons Senior Managing Director FTI Consulting United Kingdom Muhammad Programme Manager Center for Democracy and Egypt Abdelrehem Social Peace Studies Khalid Abdulla Chief Executive Officer Sekunjalo Investments Ltd South Africa Asanga Executive Director Lakshman Kadirgamar Sri Lanka Abeyagoonasekera Institute for International Relations and Strategic Studies Mahmoud Aboud Capacity Development Coordinator, Frontline Maternal and Child Health Empowerment Project, Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), Sudan Fatima Haram Acyl Commissioner for Trade and Industry, African Union, Addis Ababa Jean-Paul Adam Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Seychelles Tawia Esi Director, Ghana Legal Affairs Newmont Ghana Gold Ltd Ghana Addo-Ashong Adekeye Adebajo Executive Director The Centre for Conflict South Africa Resolution Akinwumi Ayodeji Minister of Agriculture and Rural Adesina Development of Nigeria Tosin Adewuyi Managing Director and Senior Country JPMorgan Nigeria Officer, Nigeria Olufemi Adeyemo Group Chief Financial Officer Oando Plc Nigeria Olusegun Aganga Minister of Industry, Trade and Investment of Nigeria Vikram Agarwal Vice-President, Procurement Unilever Singapore Anant Agarwal President edX USA Pascal K. Agboyibor Managing Partner Orrick Herrington & Sutcliffe France Aigboje Managing Director Access Bank Plc Nigeria Aig-Imoukhuede Wadia Ait Hamza Manager, Public Affairs Rabat School of Governance Morocco & Economics