Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marxist Crisis Theory and the Severity of the Current Economic Crisis

Marxist Crisis Theory and the Severity of the Current Economic Crisis By David M. Kotz Department of Economics Thompson Hall University of Massachusetts Amherst Amherst, MA 01003, U.S.A. December, 2009 Email Address: [email protected] This paper was presented on a panel on "Heterodox Analyses of the Current Economic Crisis" sponsored by the Union for Radical Political Economics at the Allied Social Science Associations annual convention, Atlanta, January 4, 2010. Research Assistance was provided by Ann Werboff. It is a revised version of a paper "The Final Crisis: What Can Cause a System-Threatening Crisis of Capitalism," Science & Society 74(3), July 2010. Marxist Crisis Theory and the Current Crisis, December, 2009 1 The theory of economic crisis has long occupied an important place in Marxist theory. One reason is the belief that a severe economic crisis can play a key role in the supersession of capitalism and the transition to socialism. Some early Marxist writers sought to develop a breakdown theory of economic crisis, in which an absolute barrier is identified to the reproduction of capitalism.1 However, one need not follow such a mechanistic approach to regard economic crisis as central to the problem of transition to socialism. It seems highly plausible that a severe and long-lasting crisis of accumulation would create conditions that are potentially favorable for a transition, although such a crisis is no guarantee of that outcome.2 Marxist analysts generally agree that capitalism produces two qualitatively different kinds of economic crisis. One is the periodic business cycle recession, which is resolved after a relatively short period by the normal mechanisms of a capitalist economy, although since World War II government monetary and fiscal policy have often been employed to speed the end of the recession. -

Price Spike Of

United States Department of The "Great" Price Spike of '93: Agriculture Forest Service An Analysis of Lumber and Pacific Northwest Research Station Stum.page Pr=ces =n the Research Paper PNW-RP-476 Pac=f=c Northwest August 1994 Brent L. Sohngen and Richard W. Haynes ....~ ~i!i I 11~.............. pp~L~ ~ S if!i,: ~SS ~$~ ~ ~ S$ $ $_ ss sSSos'S S$ $ S$$ s$$SsSss s ss $ sss~ ~ S sSsS~ Sss S $~ $.~ $ S$ Authors BRENT L. SOHNGEN is a graduate student, Yale University School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, New Haven, CT 06510; and RICHARD W. HAYNES is a research forester, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, Forestry Sciences Laboratory, P.O. Box 3890, Portland, OR 97208-3890. Abstract Sohngen, Brent L.; Haynes, Richard W. 1994. The "great" price spike of '93: an analysis of lumber and stumpage prices in the Pacific Northwest. Res. Pap. PNW-RP-476. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. 20 p. Lumber prices for coast Douglas-fir (Psuedotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco var. menziesil) swung rapidly from a low of $306 per thousand board feet (MBF) in September 1992 to a high of $495/MBF in March 1993. This price spike represented a sizable increase in the value of lumber over a short period, but it was not the histor- ical anomaly that many in the media would suggest. Using the theoretical relation between lumber and stumpage prices, we analyzed the interaction between these two markets over the past 82 years. Among our major findings were that there are distinct seasonal variations in monthly lumber and stumpage prices; over the longer term, these markets can be divided into three different periodsm1910 to 1944, 1945 to 1962, and 1963 to 1992; the most recent price spike did not match previous spikes in real terms; and the traditional lumber and stumpage price interaction became more significant with time but it does not seem to be as pronounced when we look at monthly prices. -

Breaking Down the Walls: the West's Challenge Operating in Euro-Asia" (2015)

University of Central Florida STARS HIM 1990-2015 2015 Breaking Down the Walls: The West's Challenge Operating in Euro- Asia Ekaterina Marchenko University of Central Florida Part of the Business Administration, Management, and Operations Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses1990-2015 University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIM 1990-2015 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Marchenko, Ekaterina, "Breaking Down the Walls: The West's Challenge Operating in Euro-Asia" (2015). HIM 1990-2015. 602. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses1990-2015/602 BREAKING DOWN THE WALLS: THE WEST’S CHALLENGES OPERATING IN EURO-ASIA by EKATERINA V. MARCHENKO A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors in the Major Program in Business Administration in the College of Business Administration and in The Burnett Honors College at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2015 Thesis Chair: Dr. Dean Cleavenger ABSTRACT Russia today presents potentially lucrative business opportunities and markets for any company interested in expanding internationally. Together with the opportunities and potential profits, however, Russia also presents formidable challenges and risks to any Western or American company considering doing business there. The purposes of this thesis are: to explain how Russia’s unique and tortured history has impacted the business culture of modern Russia; to describe the primary business risks that any Western company entering Russia will face; and to offer recommendations to any Western company considering doing business there. -

The Rise and Decline of Catching up Development an Experience of Russia and Latin America with Implications for Asian ‘Tigers’

Victor Krasilshchikov The Rise and Decline of Catching up Development An Experience of Russia and Latin America with Implications for Asian ‘Tigers’ ENTELEQUIA REVISTA INTERDISCIPLINAR The Rise and Decline of Catching up Development An Experience of Russia and Latin America with Implications for Asian `Tigers' by Victor Krasilshchikov Second edition, July 2008 ISBN: Pending Biblioteca Nacional de España Reg. No.: Pending Published by Entelequia. Revista Interdisciplinar (grupo Eumed´net) available at http://www.eumed.net/entelequia/en.lib.php?a=b008 Copyright belongs to its own author, acording to Creative Commons license: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 made up using OpenOffice.org THE RISE AND DECLINE OF CATCHING UP DEVELOPMENT (The Experience of Russia and Latin America with Implications for the Asian ‘Tigers’) 2nd edition By Victor Krasilshchikov About the Author: Victor Krasilshchikov (Krassilchtchikov) was born in Moscow on November 25, 1952. He graduated from the economic faculty of Moscow State University. He obtained the degrees of Ph.D. (1982) and Dr. of Sciences (2002) in economics. He works at the Centre for Development Studies, Institute of World Economy and International Relations (IMEMO), Russian Academy of Sciences. He is convener of the working group “Transformations in the World System – Comparative Studies in Development” of European Association of Development Research and Training Institutes (EADI – www.eadi.org) and author of three books (in Russian) and many articles (in Russian, English, and Spanish). 2008 THE RISE AND DECLINE OF CATCHING UP DEVELOPMENT Entelequia.Revista Interdisciplinar Victor Krasilshchikov / 2 THE RISE AND DECLINE OF CATCHING UP DEVELOPMENT C O N T E N T S Abbreviations 5 Preface and Acknowledgements 7 PART 1. -

Asset and Debt Deflation in the United States: How Far Can Equity Prices Fall?

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Arestis, Philip; Karakitsos, Elias Research Report Asset and debt deflation in the United States: How far can equity prices fall? Public Policy Brief, No. 73 Provided in Cooperation with: Levy Economics Institute of Bard College Suggested Citation: Arestis, Philip; Karakitsos, Elias (2003) : Asset and debt deflation in the United States: How far can equity prices fall?, Public Policy Brief, No. 73, ISBN 1931493219, Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, NY This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/54323 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu ® The Levy Economics Institute of Bard College Public Policy Brief ASSET AND DEBT DEFLATION IN THE UNITED STATES How Far Can Equity Prices Fall? PHILIP ARESTIS AND ELIAS KARAKITSOS INSTITUTE VY No. -

Structural Change for Equality an Integrated Approach to Development

2012 structural change for equality An Integrated Approach to Development Thirty-fourth San Salvador, session 27 - 31 August of eclac 2012 structural change for equality An Integrated Approach to Development Thirty-fourth San Salvador, session 27 - 31 August of eclac Alicia Bárcena Executive Secretary Antonio Prado Deputy Executive Secretary The preparation of this document was coordinated by Alicia Bárcena, Executive Secretary of ECLAC, in collaboration with Antonio Prado, Deputy Executive Secretary, Mario Cimoli, Chief of the Division of Production, Productivity and Management, Juan Alberto Fuentes, Chief of the Economic Development Division, Martin Hopenhayn, Chief of the Social Development Division and Daniel Titelman, Chief of the Financing for Development Division. The drafting committee also comprised Wilson Perés and Gabriel Porcile, in collaboration with Martín Abeles, Verónica Amarante, Filipa Correia, Felipe Jiménez, Sandra Manuelito, Juan Carlos Moreno-Brid, Esteban Pérez-Caldentey and Romain Zivy. The following chiefs of substantive divisions, subregional headquarters and national offices of ECLAC participated in the preparation of the document: Hugo Altomonte, Hugo Beteta, Luis Beccaria, Inés Bustillo, Pascual Gerstenfeld, Dirk Jaspers_Faijer, Juan Pablo Jiménez, Jorge Mattar, Carlos Mussi, Sonia Montaño, Diane Quarless, Juan Carlos Ramírez, Osvaldo Rosales and Joseluis Samaniego. Contributions and comments regarding the various chapters were provided by the following ECLAC staff members: Olga Lucía Acosta, Jean Acquatella, -

Aussie Mine 2016 the Next Act

Aussie Mine 2016 The next act www.pwc.com.au/aussiemine2016 Foreword Welcome to the 10th edition of Aussie Mine: The next act. We’ve chosen this theme because, despite gruelling market conditions and industry-wide poor performance in 2016, confidence is on the rise. We believe an exciting ‘next act’ is about to begin for our mid-tier miners. Aussie Mine provides industry and financial analysis on the Australian mid-tier mining sector as represented by the Mid-Tier 50 (“MT50”, the 50 largest mining companies listed on the Australian Securities Exchange with a market capitalisation of less than $5bn at 30 June 2016). 2 Aussie Mine 2016 Contents Plot summary 04 The three performances of the last 10 years 06 The cast: 2016 MT50 08 Gold steals the show 10 Movers and shakers 12 The next act 16 Deals analysis and outlook 18 Financial analysis 22 a. Income statement b. Cash flow statement c. Balance sheet Where are they now? 32 Key contributors & explanatory notes 36 Contacting PwC 39 Aussie Mine 2016 3 Plot summary The curtain comes up Movers and shakers The mining industry has been in decline over the last While the MT50 overall has shown a steadying level few years and this has continued with another weak of market performance in 2016, the actions and performance in 2016, with the MT50 recording an performances of 11 companies have stood out amongst aggregated net loss after tax of $1bn. the crowd. We put the spotlight on who these movers and shakers are, and how their main critic, their investors, have But as gold continues to develop a strong and dominant rewarded them. -

The UK Recession in Context — What Do Three Centuries of Data Tell Us?

Research and analysis The UK recession in context 277 The UK recession in context — what do three centuries of data tell us? By Sally Hills and Ryland Thomas of the Bank’s Monetary Assessment and Strategy Division and Nicholas Dimsdale of The Queen’s College, Oxford.(1) The Quarterly Bulletin has a long tradition of using historical data to help analyse the latest developments in the UK economy. To mark the Bulletin’s 50th anniversary, this article places the recent UK recession in a long-run historical context. It draws on the extensive literature on UK economic history and analyses a wide range of macroeconomic and financial data going back to the 18th century. The UK economy has undergone major structural change over this period but such historical comparisons can provide lessons for the current economic situation. Introduction An overview of UK business cycles The UK economy recently suffered its deepest recession since Over the past half century, enormous effort has gone into the 1930s. The recent recession had several defining constructing historical national income data for the characteristics: it took place simultaneously with a global United Kingdom. First, annual GDP estimates were recession; the financial sector was both the source and constructed back to the mid-19th century, based on output, propagator of the crisis; the exchange rate depreciated income and expenditure approaches (Deane and Cole (1962), sharply; and there was a substantial loosening of monetary Deane (1968) and Feinstein (1972)). These were followed by policy alongside a marked increase in the fiscal deficit. But ‘balanced’ estimates of GDP growth that attempted to despite UK output falling by more than 6% between 2008 Q1 reconcile these different approaches from 1870 onwards and 2009 Q3, CPI inflation remains above the Government’s (Solomou and Weale (1991) and Sefton and Weale (1995)). -

The Recent Evolution of the Natural Rate of Unemployment

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF SAN FRANCISCO WORKING PAPER SERIES The Recent Evolution of the Natural Rate of Unemployment Mary Daly Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Bart Hobijn Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Rob Valletta Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco January 2011 Working Paper 2011-05 http://www.frbsf.org/publications/economics/papers/2011/wp11-05bk.pdf The views in this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. The Recent Evolution of the Natural Rate of Unemployment MARY DALY,* BART HOBIJN, AND ROB VALLETTA Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco 101 Market Street San Francisco, CA 94105 January 17, 2011 ABSTRACT The U.S. economy is recovering from the financial crisis and ensuing deep recession, but the unemployment rate has remained stubbornly high. Some have argued that the persistent elevation of unemployment relative to historical norms reflects the fact that the shocks that hit the economy were especially disruptive to labor markets and likely to have long lasting effects. If such structural factors are at work they would result in a higher underlying natural or non- accelerating inflation rate of unemployment, implying that conventional monetary and fiscal policy should not be used in an attempt to return unemployment to its pre-recession levels. We investigate the hypothesis that the natural rate of unemployment has increased since the recession began, and if so, whether the underlying causes are transitory or persistent. -

Framing the Global Economic Downturn Crisis Rhetoric and the Politics of Recessions

Framing the global economic downturn Crisis rhetoric and the politics of recessions Framing the global economic downturn Crisis rhetoric and the politics of recessions Edited by Paul ’t Hart and Karen Tindall Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/global_economy_citation. html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Framing the global economic downturn : crisis rhetoric and the politics of recessions / editor, Paul ‘t Hart, Karen Tindall. ISBN: 9781921666049 (pbk.) 9781921666056 (pdf) Series: Australia New Zealand School of Government monograph Subjects: Financial crises. Globalization--Economic aspects. Bankruptcy--International cooperation. Crisis management--Political aspects. Political leadership. Decision-making in public administration. Other Authors/Contributors: Hart, Paul ‘t Tindall, Karen. Dewey Number: 352.3 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by John Butcher Cover images sourced from AAP Printed by University Printing Services, ANU Funding for this monograph series has been provided by the Australia and New Zealand School of Government Research Program. This edition © 2009 ANU E Press John Wanna, Series Editor Professor John Wanna is the Sir John Bunting Chair of Public Administration at the Research School of Social Sciences at The Australian National University and is the director of research for the Australian and New Zealand School of Government (ANZSOG). He is also a joint appointment with the Department of Politics and Public Policy at Griffith University and a principal researcher with two research centres: the Governance and Public Policy Research Centre and the nationally-funded Key Centre in Ethics, Law, Justice and Governance at Griffith University. -

Economic Crisis, Whether They Have a Pattern?

The 2nd ICVHE The 2nd International Conference on Vocational Higher Education (ICVHE) 2017 “The Importance on Advancing Vocational Education to Meet Contemporary Labor Demands” Volume 2018 Conference Paper Economic Crisis, Whether They Have a Pattern?—A Historical Review Rahmat Yuliawan Study Program of Secretary and Office Management, Faculty of Vocational Studies Airlangga University Abstract Purpose: The global economic recession appeared several times and became a dark history and tragedy for the world economy; the global economic crisis emerged at least 15 times, from the Panic of 1797, which lasted for recent years, to the depression in 1807, Panics of 1819, 1837, 1857, 1873, or the most phenomenal economic crisis known as the prolonged depression. This depression sustained for a 23-year period since 1873 to 1896. The collapse of the Vienna Stock Exchange caused the economic depression that spread throughout the world. It is very important to note that this phenomenon is inversely proportional to the incident in the United States, where at this period, the global industrial production is increasing rapidly. In the United States, for Corresponding Author: example, the production growth is over four times. Not to mention the panic in 1893, Rahmat Yuliawan Recession World War I, the Great Depression of 1929, recession in 1953, the Oil Crisis of Received: 8 June 2018 1973, Recession Beginning in 1980, reviewer in the early 1990s, recession, beginning Accepted: 17 July 2018 in 2000, and most recently, namely the Great Depression in 2008 due to several Published: 8 August 2018 factors, including rising oil prices caused rise in the price of food around the world, Publishing services provided by the credit crisis and the bankruptcy of various investor banks, rising unemployment, Knowledge E causing global inflation. -

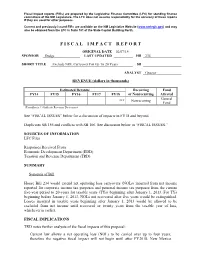

F I S C a L I M P a C T R E P O

Fiscal impact reports (FIRs) are prepared by the Legislative Finance Committee (LFC) for standing finance committees of the NM Legislature. The LFC does not assume responsibility for the accuracy of these reports if they are used for other purposes. Current and previously issued FIRs are available on the NM Legislative Website (www.nmlegis.gov) and may also be obtained from the LFC in Suite 101 of the State Capitol Building North. F I S C A L I M P A C T R E P O R T ORIGINAL DATE 02/07/14 SPONSOR Dodge LAST UPDATED HB 234 SHORT TITLE Exclude NOL Carryover For Up To 20 Years SB ANALYST Graeser REVENUE (dollars in thousands) Estimated Revenue Recurring Fund FY14 FY15 FY16 FY17 FY18 or Nonrecurring Affected General *** Nonrecurring Fund (Parenthesis ( ) Indicate Revenue Decreases) See “FISCAL ISSUES” below for a discussion of impacts in FY18 and beyond. Duplicates SB 156 and conflicts with SB 106. See discussion below in “FISCAL ISSUES.” SOURCES OF INFORMATION LFC Files Responses Received From Economic Development Department (EDD) Taxation and Revenue Department (TRD) SUMMARY Synopsis of Bill House Bill 234 would extend net operating loss carryovers (NOLs) incurred from net income reported for corporate income tax purposes and personal income tax purposes from the current five-year period to 20-years for taxable years (TYs) beginning after January 1, 2013. For TYs beginning before January 1, 2013, NOLs not recovered after five years would be extinguished. Losses incurred in taxable years beginning after January 1, 2013 would be allowed to be excluded from net income until recovered or twenty years from the taxable year of loss, whichever is earlier.