Putting the World Into World-Class Education: State Innovations and Opportunities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Education Clauses in State Constitutions Across the United States∗

Education Clauses in State Constitutions Across the United States∗ Scott Dallman Anusha Nath January 8, 2020 Executive Summary This article documents the variation in strength of education clauses in state constitu- tions across the United States. The U.S. Constitution is silent on the subject of education, but every state constitution includes language that mandates the establishment of a public education system. Some state constitutions include clauses that only stipulate that the state provide public education, while other states have taken more significant measures to ensure the provision of a high-quality public education system. Florida’s constitutional education clause is currently the strongest in the country – it recognizes education as a fundamen- tal value, requires the state to provide high-quality education, and makes the provision of education a paramount duty of the state. Minnesota can learn from the experience of other states. Most states have amended the education clause of their state constitutions over time to reflect the changing preferences of their citizens. Between 1990 and 2018, there were 312 proposed amendments on ballots across the country, and 193 passed. These amendments spanned various issues. Policymakers and voters in each state adopted the changes they deemed necessary for their education system. Minnesota has not amended its constitutional education clause since it was first established in 1857. Constitutional language matters. We use Florida and Louisiana as case studies to illus- trate that constitutional amendments can be drivers of change. Institutional changes to the education system that citizens of Florida and Louisiana helped create ultimately led to im- proved outcomes for their children. -

Questioning Conventional Wisdom About Minnesota's Public Schools

Questioning Conventional Wisdom About Minnesota’s Public Schools Joe Nathan & Laura Accomando This article goes “against the grain” of much that has been written about improving public education in the last five years. Is there something wrong with the emphasis on the “achievement gap” in studies about Minnesota education priorities? Might rural communities like Canby, Clinton, Graceville, Pierz, Lamberton, Lewiston and Lyle have things to teach affluent Minnesota suburbs, as well as inner cities? Can highly successful inner city public schools, district and charter, teach Minnesota important lessons? Are some of us misunderstanding certain lessons about the impact of high-quality early childhood education programs? For Minnesota to make significant progress, should we go beyond the constant demand for more educational funding? This article argues that the answer to each of these questions is “yes.” Moreover, Minnesota’s leadership and success with many students may, as has happened in the past, make big changes more difficult. Yet, as Abraham Lincoln once noted, “The dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate to the stormy present” (Lincoln). We need more ambitious goals, and significant institutional changes to reach those goals. Where should we be heading? This article will suggest that a new model of public education should have as its central goals within the next five years: 1. Completion of some form of post-secondary education, two or four years, by at least 95% of Minnesota students within six years of the time they graduate from high school. 2. 95% of students who enter Minnesota public colleges and universities fully prepared in reading, writing and math for this work. -

Building an Equitable School System for All Students and Educators

Building an Equitable School System for All Students and Educators Table of contents EPIC Advisory Teams 1 The Educator Compensation and Work Environments Team 1 The Teacher Induction and Mentoring Team 1 The Infrastructure Team 2 The Pre-K Team 2 The Trauma-Informed, Restorative Schools Team 3 The Teacher Preparation Team 3 The Support Services Team 4 The Full-Service Community Schools Team 4 The Public Higher Education Team 5 The Special Education Team 5 Introduction: Building an Equitable School System for All Students and Educators 6 Education Funding Shortfalls in Minnesota 9 Equity and Minnesota’s Public Schools: Achievement Gaps, Discipline Gaps, and Legacies of White Supremacy 12 Minnesota’s Teacher Exodus 15 What We Must Do, Together 18 1. Educator compensation and work environments 18 2. Teacher mentoring and induction 18 3. School infrastructure 19 4. Preschool 19 5. Trauma-informed, restorative schools 19 6. Teacher preparation 20 7. Support professionals 20 8. Full-service community schools 20 9. Public higher education 21 10. Special education 21 References: Introduction 22 Educator Compensation and Work Environments 24 Cost of Living for Minnesota Educators 31 Oppositional Voices: Market-Based Positions on Educator Compensation 33 The Educator Wage Gap: National and Minnesota Specific Trends 36 The Professional Wage Gap Disproportionately Harms Female Educators 40 Education Support Professionals Do Not Earn a Living Wage 43 Inadequate Educator Benefits Further Contribute to the Professional Wage Gap 44 Student Loan Debt -

Cost of Educatiqn in Minnesota

Determining the ·cost of EducatiQn in Minnesota Continuing the Work of the Governor's Education Funding Reform Task Force EXECUTIVE SUMMARY December 2, 2005 Prepared by John Myers, Vice President of Augenblick, Palaich and Associates for the Association ofMetropolitan School Districts, Minnesota Rural Education Association and Schools for Equity in Education BACKGROUND The Education Finance Reform Task Force believes that Minnesota has much about which to be proud when it comes to our public schools. Thus begins "Investing In Our Future: Seeking a Fair, Understandable and Accountable Twenty First Century Education Finance System for Minnesota," an historic report commissioned in 2003 by Minnesota Governor Tim Pawlentywho appointed a 19-member Task-Force to examine issues of education reform critical to the success of Minnesota students. "Investing In Our Future," widely examined and often referenced by both lawmakers and educators, proved to be an excellent vehicle by which this important policy discussion has moved forward. Yet, by the Task Force's own admission, the group "was not charged with developing or determining what the final funding levels should be in Minnesota." Instead, the creation of a formula which must be "logically linked to ... student learning" and "sufficient to cover full dollar costs of ensuring Minnesota public school students have an opportunity to achieve state specified academic standards" was left incomplete. The Task Force, with expert support from .Management Analysis & Planning, Inc. (MAP), suggested that a "rationally determined process could be developed," but Task Force members and observers alike have noted that the work itself has yet to be done. While a new funding system was not created, the Governor's Task Force did recommend several next steps in the implementation of a new education funding system. -

Minnesota Arts Education Research Project BUILDING a LEGACY Perpich Goals and Results the Minnesota Arts Education Research Project

Front Cover Inside Front Cover Key Findings While access to arts programs is nearly universal (99% of schools) less than half of all middle and high schools and only 28% of elementary schools provide the required number of arts areas. 87% of schools have aligned their curriculum with the state arts standards. Assessment of student skills and knowledge is mostly driven by teacher-developed assessments with fewer than 3 in 10 schools reporting district developed assessments in the arts. Nearly ½ of all high schools include the arts in School Improvement Plans. 92% of elementary, 77% of middle and 49% of high school students participate in at least one arts area in one year, with music and visual arts having the highest enrollments. Nearly all schools (92%) use licensed arts teachers (full time or part-time) as the primary provider of music and visual arts instruction. 75% of schools report having no arts coordinator in their school or district. Nearly 2/3 of schools spend less than $10 per pupil per year for arts instructional materials. At the elementary level, the per-pupil arts spending is only 2 cents per day. To support direct arts instruction, 23% of all schools reported using outside funding to offset budget decreases and nearly half of all schools charge fees for extracurricular arts activities. While 46% of all schools report using arts integration as a teaching strategy, only 15% reported using this strategy on a regular basis. 67% of schools indicate a desire to introduce or increase arts integration. 93% of all schools reported providing students field trips to museums, theaters, musical performances and exhibitions to engage in artistic experiences. -

Education Reform in Minnesota: Profile of Learning and the Instructional Role of the School Library Media Specialist

Volume 9, 2006 Approved March 2006 ISSN: 1523-4320 www.ala.org/aasl/slr Education Reform in Minnesota: Profile of Learning and the Instructional Role of the School Library Media Specialist Marie E. Kelsey, Professor, College of St. Scholastica, Duluth, Minnesota Between 1998 and 2003, a Minnesota educational reform movement named the Profile of Learning (POL) generated high levels of school library media center use in high schools and contributed to the fulfillment of the instructional role of the school library media specialist (SLMS) as described in Information Power . POL consisted of graduation standards with accompanying projects assigned to students to meet those standards. Projects were process- oriented, requiring research, reading, reflection, and synthesis of ideas. School library media center resources and services were increasingly in demand during this era. To learn more about how school library media centers and SLMSs were affected during this reform movement, the researcher sent a survey to 174 high school SLMSs. After the survey results were tallied, twelve interviews were held with selected SLMSs. Although teachers had a negative opinion of the POL era, SLMSs felt energized, important, and effective in their increasing roles of collaboration and instruction in student education during this time. The researcher also contrasted survey and interview findings with past research on the SLMS role. POL was rescinded by the Minnesota legislature before the affects of increased collaboration and resource-based learning could be assessed. The following study examines the roles and attitudes of SLMSs during the POL era, with an emphasis on the increased instructional role. In Information Power: Building Partnerships for Learning (AASL and AECT 1998), there is a logo visually representing the components of a learning-centered school library media center. -

Members of the Minnesota Legislature, We Are an Assemblage

Members of the Minnesota legislature, We are an assemblage of legal scholars and experts who specialize in civil rights and education. We write to express our concern over potential changes to the education clause of the Minnesota Constitution, recently proposed by the Minneapolis Federal Reserve. Although we share your concern over ongoing disparities in Minnesota schools, and would welcome efforts to strengthen education rights in the state, the proposed amendment is unlikely to achieve this aim. The Federal Reserve proposal eliminates, in its entirety, the existing education clause in the Minnesota Constitution – a provision which dates to the document’s adoption in 1857. In doing so, it removes critically important language that has already been held by the Minnesota Supreme Court to protect students’ civil rights. The proposed new language would not necessarily safeguard these rights. The proposed incorporation of several undefined adjectives like “quality” or “paramount” into the education clause would not, on its own, create new legal protections or requirements that do not already exist in Minnesota law. In addition, the proposed amendment also contains qualifying language that might further narrow the scope of students’ rights below the standard that exists in current law. The existing Education Clause of the Minnesota Constitution reads as follows: The stability of a republican form of government depending mainly upon the intelligence of the people, it is the duty of the legislature to establish a general and uniform system of public schools. The legislature shall make such provisions by taxation or otherwise as will secure a thorough and efficient system of public schools throughout the state.1 This language has been held to give rise to several major constitutional rights. -

Overview of Indian Education Laws and Policies

Overview of Indian Education Laws and Policies IHSL Statewide Training Rutger’s Resort Deerwood, MN December 4, 2015 Dennis W. Olson, Director Office of Indian Education “Leading for educational excellence and equity. Every day for every one.” 11 Reservations and Communities in Minnesota • Ojibwe Reservations – Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe – Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa – White Earth Nation – Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe – Red Lake Nation – Bois Forte Band of Chippewa – Grand Portage Band of Ojibwe • Dakota Communities – Prairie Island Indian Community – Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community – Upper Sioux Community – Lower Sioux Indian Community education.state.mn.us 2 Where are Minnesota’s Tribal Communities Located? www.mnhum.org www.treatiesmatter.org education.state.mn.us 3 Where are American Indian Students Concentrated? www.mnrea.org education.state.mn.us 4 Where do American Indian Students Attend School? • Large majority of students attend public schools – 19,768 K-12 in 2014-2015 – 2.3% of Total Student Population – 1/3 in 7-county metro – 2/3 in Greater MN • 4 Tribal Schools (BIE Grant Funded) – 837 students statewide (4.2% of all Indian Students) . Fond du Lac Ojibwe School (Fond du Lac) . Nay Ah Shing Schools (Mille Lacs) . Circle of Life Academy (White Earth) . Bug O Nay Ge Shig School (Leech Lake) education.state.mn.us 5 Where do American Indian Students Attend School? education.state.mn.us 6 Minnesota AMI Graduation Rate AMI Graduation Rate 2011-2014 52 50 48 46 AMI Gradution Rate 44 42 40 38 2011 2012 2013 2014 3-year increase of 8.19% education.state.mn.us 7 Federal Indian Education: History, Policy, Programs Indian Education: A National Tragedy – A National Challenge (1969) Sen. -

The Roots of Higher Education in Minnesota

THE St. Cloud Normal School's building in 1874 The ROOTS of Higher Education in Minnesota OLIVER C. CARMICHAEL I AM SENSIBLE OF the high honor you than I —I am nevertheless grateful to you have done me in inviting me to deliver this for giving me the opportunity and the occa address at the one-hundred-and-fifth an sion for exploring what seems to me to be nual meeting of the Minnesota Historical one of the richest backgrounds of higher Society, though at the moment I confess education provided by any of the forty- to great trepidation as I undertake the task eight states. The fascinating material which assigned me. While I do not know by what reached me from the several institutions right I should speak to you on the "Roots has engaged my attention far into the nights of Higher Education in Minnesota" — for of many days that were filled with heavy many of you know so much more about it administrative duties. But it has provided relaxation and a degree of excitement, since DR. CARMICHAEL scrvcd for sevcu years as it has given me a new sense of the variety president of the Carnegie Foundation for the and richness of the sources of motivation Advancement of Teaching before assuming the and inspiration which gave rise to the presidency of the University of Alabama in American system of higher education and 1953. This address was presented on May 11, 1954, before the luncheon session of the which still undergird it. society's annual meeting at the Curtis Hotel, Obviously, I cannot do justice to the sub Minneapolis. -

Minnesota School Finance: a Guide for Legislators About This Publication This Guidebook Explains How Public Elementary and Secondary Schools Are Funded in Minnesota

Minnesota School Finance: A Guide for Legislators About this Publication This guidebook explains how public elementary and secondary schools are funded in Minnesota. By Tim Strom, Legislative Analyst November 2019 Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................ 2 School Finance Terminology ................................................................................. 11 Property Tax System Terminology ........................................................................ 18 Counting Students ................................................................................................. 20 General Education Revenue.................................................................................. 22 School Transportation ........................................................................................... 43 Capital Finance ...................................................................................................... 44 Special Education .................................................................................................. 57 American Indian Programs.................................................................................... 61 Community, Early Childhood, and Adult Education ............................................. 64 Cooperative Programs ......................................................................................... -

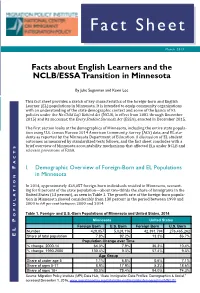

Facts About English Learners and the NCLB/ESSA Transition in Minnesota

Fact Sheet March 2017 Facts about English Learners and the NCLB/ESSA Transition in Minnesota By Julie Sugarman and Kevin Lee This fact sheet provides a sketch of key characteristics of the foreign-born and English Learner (EL) populations in Minnesota. It is intended to equip community organizations with an understanding of the state demographic context and some of the basics of EL policies under the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB, in effect from 2002 through December 2015) and its successor, the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), enacted in December 2015. The first section looks at the demographics of Minnesota, including the entire state popula- tion using U.S. Census Bureau 2014 American Community Survey (ACS) data, and EL stu- dents as reported by the Minnesota Department of Education. A discussion of EL student outcomes as measured by standardized tests follows, and the fact sheet concludes with a brief overview of Minnesota accountability mechanisms that affected ELs under NCLB and relevant provisions of ESSA. ACTS I. Demographic Overview of Foreign-Born and EL Populations F in Minnesota In 2014, approximately 428,057 foreign-born individuals resided in Minnesota, account- TION ing for 8 percent of the state population—about two-thirds the share of immigrants in the A United States (13 percent), as seen in Table 1. The growth rate of the foreign-born popula- L tion in Minnesota slowed considerably from 130 percent in the period between 1990 and 2000 to 64 percent between 2000 and 2014. U P Table 1. Foreign- and U.S.-Born Populations of Minnesota and United States, 2014 O Minnesota United States Foreign Born U.S. -

Postsecondary Planning

POSTSECONDARY PLANNING: A JOINT REPORT TO THE MINNESOTA LEGISLATURE February 2019 Minnesota State University of Minnesota For further information or additional copies, contact: Office of Government Relations University of Minnesota 612-626-9234 government-relations.umn.edu or Minnesota State 651-201-1800 1-888-MINNESOTA STATE4U www.MinnState.edu/media/publications/ Contents Executive Summary 1 I. Introduction 2 II. Collaborative Programs and Services 4 Academic Program Partnerships Minnesota Cooperative Admissions Program (MnCAP) Rochester Partnership Center for Allied Health Programs and HealthForce Minnesota University of Minnesota Extension Library and Information Technology eLearning Other Collaborative Initiatives III. Program Duplication 14 IV. Credit Transfer 16 Policies and Practices Cooperative Transfer Programs V. College Readiness and Under-Prepared Students 19 P-20 Education Partnership Postsecondary Enrollment Options (PSEO) College Preparation College Readiness Research VI. Conclusion 24 Appendix: Collaborative Academic Programs 25 Minnesota Session Laws 2003, Regular Session, Chapter 133, Article 1, Section 7. POSTSECONDARY SYSTEMS As part of the boards' biennial budget requests, the board of trustees of the Minnesota State Colleges and Universities and the board of regents of the University of Minnesota shall report to the legislature on progress under the master academic plan for the metropolitan area. The report must include a discussion of coordination and duplication of program offerings, developmental and remedial education, credit transfers within and between the postsecondary systems, and planning and delivery of coordinated programs. In order to better achieve the goal of a more integrated, effective, and seamless postsecondary education system in Minnesota, the report must also identify statewide efforts at integration and cooperation between the postsecondary systems.