Rereading Paul's God-, Christ-, and Spirit-Language in Conversation with Trinitarian Theologies of Persons and Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Subjugation IV

Subjugation 4 Tribulation by Fel (aka James Galloway) ToC 1 To: Title ToC 2 Chapter 1 Koira, 18 Toraa, 4401, Orthodox Calendar Wednesday, 28 January 2014, Terran Standard Calendar Koira, 18 Toraa, year 1327 of the 97th Generation, Karinne Historical Reference Calendar Foxwood East, Karsa, Karis Amber was starting to make a nuisance of herself. There was just something intrinsically, fundamentally wrong about an insufferably cute animal that was smart enough to know that it was insufferably cute, and therefore exploited that insufferable cuteness with almost ruthless impunity. In the 18 days since she’d arrived in their house, she’d quickly learned that she could do virtually anything and get away with it, because she was, quite literally, too cute to punish. Fortunately, thus far she had yet to attempt anything truly criminal, but that didn’t mean that she didn’t abuse her cuteness. One of the ways she was abusing it was just what she was doing now, licking his ear when he was trying to sleep. Her tiny little tongue was surprisingly hot, and it startled him awake. “Amber!” he grunted incoherently. “I’m trying to sleep!” She gave one of her little squeaking yips, not quite a bark but somewhat similar to it, and jumped up onto his shoulder. She didn’t even weigh three pounds, she was so small, but her little claws were like needles as they kneaded into his shoulder. He groaned in frustration and swatted lightly in her general direction, but the little bundle of fur was not impressed by his attempts to shoo her away. -

Irish Pop Music in a Global Context by Oliver Patrick Cunningham

Irish Pop Music in a Global Context By Oliver Patrick Cunningham Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Regulations for the Attainment of the Degree of Masters of Arts in Sociology. National University of Ireland, Maynooth, Co. Kildare. Department of Sociology. July, 2000. Head of Department: Professor Liam Ryan. Research Supervisor: Dr. Colin Coulter. Acknowledgements There are gHite a number of people / wish to thank for helping me to complete this thesis. First and most important of all my family for their love and support notJust in my academic endeavors but also in all my different efforts so far, Thanks for your fate! Second / wish to thank all my friends both at home and in college in Maynooth for listening to me for the last ten months as I put this work together also for the great help and advice they gave to me during this period. Thanks for listeningl Third I wish to thank the staff in the Department of Sociology Nidi Maynooth, especially Dr, Colin Coulter my thesis supervisor for all their help and encouragement during the last year. Thanks for the knowledge/ Fourth / wish to thank the M A sociology class of 1999-2000 for being such a great class to learn, work and be friends with. Thanks for a great year! Fifth but most certainly not last / want to thank one friend who unfortunately was with us at the beginning of this thesis and gave me great encouragement to pursue it but could not stay to see the end result, This work is dedicated to your eternal memory Aoife. -

Hegel, Sade, and Gnostic Infinities

Radical Orthodoxy: Theology, Philosophy, Politics, Vol. 1, Number 3 (September 2013): 383-425. ISSN 2050-392X HEGEL, SADE, AND GNOSTIC INFINITIES Cyril O’Regan lavoj Žižek not only made the impossible possible when he articulated an inner relation between Kant and de Sade, but showed that the impossible was necessary.1 The impossibility is necessary because of the temporal contiguity of thinkers who articulate two very different S versions of the Enlightenment, who variously support autonomy, and who feel called upon to take a stance with respect to Christian discourse and practice. As the demand for articulation is pressed within a horizon of questioning, proximally defined by the Lacanian problematic of self-presentation and horizonally by Adorno and Horkheimmer’s dialectic of the Enlightenment, Žižek would be the first to agree that his investigation is probative. One could press much more the issue of whether the logic of Kant’s view on radical evil is in fact that of the demonic, while much more could be said about the Enlightenment’s inversion in the ‘mad’ discourse of Sade and the relation- difference between both discourses and the Christian discourses that are objects of critique. However important it would be to complete this task, it seems even more necessary to engage the question of the relation between Hegel and Sade. More necessary, since not only is such a relation left unexplored while hinted at 1 See Žižek’s essay ‘On Radical Evil and Other Matters,’ in Tarrying with the Negative: Kant, Hegel, and the Critique of Ideology (Durham: Duke University Press, 1993), pp. -

POSTMODERN CRITICAL WESLEYANISM: WESLEY, MILBANK, NIHILISM, and METANARRATIVE REALISM Henry W

POSTMODERN CRITICAL WESLEYANISM: WESLEY, MILBANK, NIHILISM, AND METANARRATIVE REALISM Henry W. Spaulding II, Ph.D. Introduction This paper is offered in the hope of beginning a sustained conversation between Wesleyan-Holiness theology and Radical Orthodoxy. Such a conversation is necessitated by the emergence of postmodern philosophy/theology in all of its diversity. It would be a serious mistake to deny either the challenge or possibility presented by this moment in the history of Wesleyan-Holiness theology. Radical Orthodoxy understands the threat presented by postmodernism along with its limited possibilities. Perhaps, it is at this point that Radical Orthodoxy reveals its resonance with Wesleyan-Holiness most clearly. John Milbank, at least, is rather forthright in his admission that Radical Orthodoxy owes its inspiration to Methodism and holiness theology. This should give those of us within the Wesleyan-Holiness tradition sufficient reason to think more fully about possible connections between these two ways of engaging culture theologically. Some of this conversation revolves around nihilism. The sundering of meaning suggested by nihilism points to the failure of the Enlightenment project and simultaneously challenges theology to gather its resources in order to constructively address issues of faith and practice. Radical Orthodoxy (RO) sees the threat posed by nihilism and proposes that the resources of the Christian faith are sufficient to confront its challenges. It is quite possible that RO has more to gain from a sustained conversation with Wesleyan-Holiness theology than many realize. The most significant benefit of this conversation for RO centers on the seriousness with which Wesley embraced primitive Christian practice, fundamental orthodoxy, and the plain sense of scripture. -

Being Is Double

Being is double Jean-Luc Marion and John Milbank on God, being and analogy Nathan Edward Lyons B. A. (Adv.) (Hons.) This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy School of Philosophy Australian Catholic University Graduate Research Office Locked Bag 4115 Fitzroy, Victoria 3065 1st March 2014 i ABSTRACT This thesis examines the contemporary dispute between philosopher Jean-Luc Marion and theologian John Milbank concerning the relation of God to being and the nature of theological analogy. I argue that Marion and Milbank begin from a shared opposition to Scotist univocity but tend in opposite directions in elaborating their constructive theologies. Marion takes an essentially Dionysian approach, emphasising the divine transcendence “beyond being” to such a degree as to produce an essentially equivocal account of theological analogy. Milbank, on the other hand, inspired particularly by Eckhart, affirms a strong version of the Thomist thesis that God is “being itself” and emphasises divine immanence to such a degree that the analogical distinction between created and uncreated being is virtually collapsed. Both thinkers claim fidelity to the premodern Christian theological tradition, but I show that certain difficulties attend both of their claims. I suggest that the decisive issue between them is the authority which should be granted to Heidegger’s account of being and I argue that it is Milbank’s vision of post-Heideggerian theological method which is to be preferred. I conclude that Marion and Milbank give two impressive contemporary answers to the ancient riddle of “double being” raised in the Anonymous Commentary on Plato’s “Parmenides,” a riddle which queries the relation between absolute First being and derived Second being. -

Title "Stand by Your Man/There Ain't No Future In

TITLE "STAND BY YOUR MAN/THERE AIN'T NO FUTURE IN THIS" THREE DECADES OF ROMANCE IN COUNTRY MUSIC by S. DIANE WILLIAMS Presented to the American Culture Faculty at the University of Michigan-Flint in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Liberal Studies in American Culture Date 98 8AUGUST 15 988AUGUST Firs t Reader Second Reader "STAND BY YOUR MAN/THERE AIN'T NO FUTURE IN THIS" THREE DECADES OF ROMANCE IN COUNTRY MUSIC S. DIANE WILLIAMS AUGUST 15, 19SB TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface Introduction - "You Never Called Me By My Name" Page 1 Chapter 1 — "Would Jesus Wear A Rolen" Page 13 Chapter 2 - "You Ain’t Woman Enough To Take My Man./ Stand By Your Man"; Lorrtta Lynn and Tammy Wynette Page 38 Chapter 3 - "Think About Love/Happy Birthday Dear Heartache"; Dolly Parton and Barbara Mandrell Page 53 Chapter 4 - "Do Me With Love/Love Will Find Its Way To You"; Janie Frickie and Reba McEntire F'aqe 70 Chapter 5 - "Hello, Dari in"; Conpempory Male Vocalists Page 90 Conclusion - "If 017 Hank Could Only See Us Now" Page 117 Appendix A - Comparison Of Billboard Chart F'osi t i ons Appendix B - Country Music Industry Awards Appendix C - Index of Songs Works Consulted PREFACE I grew up just outside of Flint, Michigan, not a place generally considered the huh of country music activity. One of the many misconception about country music is that its audience is strictly southern and rural; my northern urban working class family listened exclusively to country music. As a teenager I was was more interested in Motown than Nashville, but by the time I reached my early thirties I had became a serious country music fan. -

Psychedelia, the Summer of Love, & Monterey-The Rock Culture of 1967

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2012 Psychedelia, the Summer of Love, & Monterey-The Rock Culture of 1967 James M. Maynard Trinity College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the American Film Studies Commons, American Literature Commons, and the American Popular Culture Commons Recommended Citation Maynard, James M., "Psychedelia, the Summer of Love, & Monterey-The Rock Culture of 1967". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2012. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/170 Psychedelia, the Summer of Love, & Monterey-The Rock Culture of 1967 Jamie Maynard American Studies Program Senior Thesis Advisor: Louis P. Masur Spring 2012 1 Table of Contents Introduction..…………………………………………………………………………………4 Chapter One: Developing the niche for rock culture & Monterey as a “savior” of Avant- Garde ideals…………………………………………………………………………………...7 Chapter Two: Building the rock “umbrella” & the “Hippie Aesthetic”……………………24 Chapter Three: The Yin & Yang of early hippie rock & culture—developing the San Francisco rock scene…………………………………………………………………………53 Chapter Four: The British sound, acid rock “unpacked” & the countercultural Mecca of Haight-Ashbury………………………………………………………………………………71 Chapter Five: From whisperings of a revolution to a revolution of 100,000 strong— Monterey Pop………………………………………………………………………………...97 Conclusion: The legacy of rock-culture in 1967 and onward……………………………...123 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………….128 Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………..131 2 For Louis P. Masur and Scott Gac- The best music is essentially there to provide you something to face the world with -The Boss 3 Introduction: “Music is prophetic. It has always been in its essence a herald of times to come. Music is more than an object of study: it is a way of perceiving the world. -

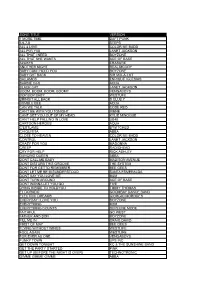

Song Title Version 1 More Time Daft Punk 5,6,7,8 Steps All 4 L0ve Color Me Badd All F0r Y0u Janet Jackson All That I Need Boyzon

SONG TITLE VERSION 1 MORE TIME DAFT PUNK 5,6,7,8 STEPS ALL 4 L0VE COLOR ME BADD ALL F0R Y0U JANET JACKSON ALL THAT I NEED BOYZONE ALL THAT SHE WANTS ACE OF BASE ALWAYS ERASURE ANOTHER NIGHT REAL MCCOY BABY CAN I HOLD YOU BOYZONE BABY G0T BACK SIR MIX-A-LOT BAILAMOS ENRIQUE IGLESIAS BARBIE GIRL AQUA BLACK CAT JANET JACKSON BOOM, BOOM, BOOM, BOOM!! VENGABOYS BOP BOP BABY WESTUFE BRINGIT ALL BACK S CLUB 7 BUMBLE BEE AQUA CAN WE TALK CODE RED CAN'T BE WITH YOU TONIGHT IRENE CANT GET YOU OUT OF MY HEAD KYLIE MINOGUE CAN'T HELP FALLING IN LOVE UB40 CARTOON HEROES AQUA C'ESTLAVIE B*WITCHED CHIQUITITA ABBA CLOSE TO HEAVEN COLOR ME BADD CONTROL JANET JACKSON CRAZY FOR YOU MADONNA CREEP RADIOHEAD CRY FOR HELP RICK ASHLEY DANCING QUEEN ABBA DONT CALL ME BABY MADISON AVENUE DONT DISTURB THIS GROOVE THE SYSTEM DONT FOR GETTO REMEMBER BEE GEES DONT LET ME BE MISUNDERSTOOD SANTA ESMERALDA DONT SAY YOU LOVE ME M2M DONT TURN AROUND ACE OF BASE DONT WANNA LET YOU GO FIVE DYING INSIDE TO HOLDYOU TIMMY THOMAS EL DORADO GOOMBAY DANCE BAND ELECTRIC DREAMS GIORGIO MORODES EVERYDAY I LOVE YOU BOYZONE EVERYTHING M2M EVERYTHING COUNTS DEPECHE MODE FAITHFUL GO WEST FATHER AND SON BOYZONE FILL ME IN CRAIG DAVID FIRST OF MAY BEE GEES FLYING WITHOUT WINGS WESTLIFE FOOL AGAIN WESTLIFE FOR EVER AS ONE VENGABOYS FUNKY TOWN UPS INC GET DOWN TONIGHT KC & THE SUNSHINE BAND GET THE PARTY STARTED PINK GET UP (BEFORE THE NIGHT IS OVER) TECHNOTRONIC GIMME GIMME GIMME ABBA HAPPY SONG BONEY M. -

Radical Orthodoxy: Theology, Philosophy, Politics, Vol

Radical Orthodoxy: Theology, Philosophy, Politics, Vol. 2, Number 2 (June 2014): 222-43. ISSN 2050-392X Radical Orthodoxy: Theology, Philosophy, Politics Awakening to Life: Augustine’s Admonition to (would-be) Philosophers Ian Clausen Introduction rom the earliest point in his post-conversion career, Augustine plumbed the origin and destiny of life. Far from a stable status he could readily F rely on, life presented itself as a question that demanded his response. In this article, I explore the manner in which Augustine approaches life. Focusing on his first two dialogues, De Academicis (386)1 and De beata vita (386),2 I trace 1 This work is more familiar to us as Contra Academicos, though this title apparently reflects a later emendation (see retr., 1.1.1). The later title also implies a more polemical stance toward scepticism that contrasts with the content of the dialogue itself; as Augustine also indicates around AD 386 (in a letter to Hermogenianus, an early reader of De Academicis), his intention was never to “attack” the Academics, but to “imitate” their method of philosophy. Cf. ep., 1.1. For the earlier title De Academicis see Conybeare, Catherine, The Irrational Augustine (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006). 2 The so-called Cassiciacum discourse includes four complete dialogues, and De Academicis and De beata vita are the first two in the series. On the narrative ordering of the dialogues, compare the contrasting interpretations in Cary, Phillip, “What Licentius Learned: A Narrative Reading of the Cassiciacum Dialogues,” in Augustinian Studies 29:1 (1998): 161-3, Radical Orthodoxy 2, No. -

Open THESIS.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATION ARTS AND SCIENCES IDENTITY AND HIP-HOP: AN ANALYSIS OF EGO-FUNCTION IN THE COLLEGE DROPOUT AND THE MISEDUCATION OF LAURYN HILL LAURA KASTNER SPRING 2017 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in Communication Arts & Sciences and Statistics with honors in Communication Arts & Sciences Reviewed and approved* by the following: Anne Demo Assistant Professor of Communication Arts & Sciences Thesis Supervisor Lori Bedell Senior Lecturer of Communication Arts & Sciences Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT In this thesis, I will be analyzing how Kanye West and Lauryn Hill create identity for themselves and their listeners in the albums The College Dropout and The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, respectively. Identity creation will be analyzed using Richard Gregg’s concept of ego-function. By applying the three stages of the theory – victimization of the ego, demonization of the enemy, and reaffirmation of the ego – to both albums, I hope to uncover the ways that both West and Hill contribute to identity creation. I also discuss the ways in which they create identity that cannot be explained by ego-function theory. I also briefly address the following questions: (1) How does the language of ego-function differ between the artists? (2) How does their music speak to listeners of different ethnicities? (3) What role does gender play in ego-function? Does the language of ego-function differ between genders? ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ………………………………………………………………......iii Chapter 1 Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Kanye West: The Jerk and the Genius ............................................................................ -

Radical Orthodoxy, Political Ecclesiologies, and the Secular State

International Journal of Philosophy and Theology June 2014, Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 155-164 ISSN: 2333-5750 (Print), 2333-5769 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). 2014. All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development Radical Orthodoxy, Political Ecclesiologies, and the Secular State W. James Yazell 1 Introduction Most people recognize the separation of Church and State to be one of the fundamental values of America. This view can be characterized as Secular Modernity, where the public sphere is seen as a religiously neutral ground. Those who oppose this separation are usually Christian Evangelicals (and sometimes Roman Catholics) who are a part of a conservative movement that began in the 1970's with the goal of creating greater influence over politics. Even so, most Evangelicals would still recognize that the U.S. Government should not establish its own church, but should rather be influenced by their own brand of conservative Christian values. Thus, most Americans will agree that some level of separation between the Church and the State is warranted, the disagreement is instead over just how much separation there ought to be. The historical precedent is certainly in favor of a separation in America. Thomas Jefferson famously interprets (in a letter to a worried Baptist minister) the First Amendment to be a “wall of separation between church and State” which the supreme court has used in a number of court cases (Wiecek). Article II of the English version of the Treaty of Tripoli went so far as to state that the U.S. Government is in no way founded on the Christian religion. -

Joseph Ratzinger's Understanding of Freedom

Volume 2, no. 3 | December 2014 RADICAL ORTHODOXTY Theology, Philosophy, Politics R P OP Radical Orthodoxy: Theology, Philosophy, Politics Editorial Board Phillip Blond Rudi A. te Velde Conor Cunningham Evandro Botto Graham Ward Andrew Davison David B. Burrell, C.S.C. Thomas Weinandy, OFM Cap. Alessandra Gerolin David Fergusson Slavoj Žižek Michael Hanby Lord Maurice Glasman Samuel Kimbriel Boris Gunjević Editorial Team John Milbank David Bentley Hart Editor: Simon Oliver Stanley Hauerwas Christopher Ben Simpson Adrian Pabst Johannes Hoff Catherine Pickstock Austen Ivereigh Managing Editor & Layout: Aaron Riches Fergus Kerr, OP Eric Austin Lee Tracey Rowland Peter J. Leithart Neil Turnbull Joost van Loon Copy Editor: James Macmillan Seth Lloyd Norris Thomas Advisory Board Mgsr. Javier Martínez Talal Asad Alison Milbank Reviews Editor: William Bain Michael S Northcott Brendan Sammon John Behr Nicholas Rengger John R. Betz Michael Symmons Roberts Oliva Blanchette Charles Taylor Radical Orthodoxy: A Journal of Theology, Philosophy and Politics (ISSN: 2050-392X) is an internationally peer reviewed journal dedicated to the exploration of academic and policy debates that interface between theology, philosophy and the social sciences. The editorial policy of the journal is radically non-partisan and the journal welcomes submissions from scholars and intellectuals with interesting and relevant things to say about both the nature and trajectory of the times in which we live. The journal intends to publish papers on all branches of philosophy, theology aesthetics (including literary, art and music criticism) as well as pieces on ethical, political, social, economic and cultural theory. The journal will be published four times a year; each volume comprising of standard, special, review and current affairs issues.