Rundheersing Bheenick: Escaping the Fate of the Dodo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ex-Father of the Nation - the New York Times

Ex-Father of the Nation - The New York Times http://www.nytimes.com/2001/04/15/books/ex-father-of-the-nation.htm... April 15, 2001 By Pankaj Mishra GANDHI'S PASSION The Life and Legacy of Mahatma Gandhi. By Stanley Wolpert. Illustrated. 308 pp. New York: Oxford University Press. $27.50. In 1894, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi arrived in South Africa as a young shiftless lawyer from India. He planned to spend a year; he ended up spending two extraordinary decades during which he moved from being the resentful victim of local racial humiliations to the initiator of a wholly new kind of political activism based upon nonviolence. When he finally left South Africa in 1914, after having organized a small and frequently trampled-upon Indian minority into a significant political force, his greatest Afrikaner adversary, Gen. Jan Smuts, was relieved enough to write to a friend, ''The saint has left our shores, I hope, forever.'' More than 30 years later, a few months after India's long-delayed independence in 1947, Gandhi was assassinated by a Hindu Brahmin named Nathuram Godse, who turned out to have been one of the many rationalists exasperated and bewildered by Gandhi. In a remarkably coherent statement in court, Godse explained that he had killed Gandhi in order to cleanse India of such ''old superstitious beliefs'' as the ''power of the soul, the inner voice, the fast, the prayer and the purity of the mind.'' He had felt that nonviolence of the kind Gandhi advocated could only ''lead the nation toward ruin.'' With Gandhi out of the way, Godse said, India would be ''free to follow the course founded on reason which I consider to be necessary for sound nation-building''; it would ''surely be practical, able to retaliate, and would be powerful with armed forces.'' Far from being a lone gunman, Godse spoke for millions of educated Hindus, including some of Gandhi's closest disciples, who felt that the ''father of the nation'' was a burden upon a country that now had to be governed in modern, rational ways. -

„Arab Spring“ and the Thai Elections

Between the „Arab Spring“ and the Thai elections The months long reporting on the unrest in the Arab world misses one important point; each and every country engulfed by the popular revolt is a republic, while monarchies (situated predominantly on the Arabian Peninsula, GCC) remain largely intact. Difference between e.g. Libya or Tunisia and Saudi Arabia or U.A.E. is not only geographic – it is fundamental. The first are formal democracies of republican type (traditionally promoting a secular pan-Arabism) and later are real autocracies of hereditary monarchy type (closer to the rightist Islamic than a pan-Arabic ideology). Since its independence, Tunisia, Libya or Egypt have kept democratic election process and institutional setup of executive, judicial and legislative branch – in formal sense, although in reality they have often been run by the alienated power structures of over-dominant party leader (guardian of revolution, or other sort of „father of the nation‟). Authoritarian monarchies have been, and still are ruled by a direct royal decree without even formally electable democratic institutions. Modern political history analyses give us a powerful reminder that the most exposed and most vulnerable states are countries transitioning from a formal to a real democracy. Despotic absolutistic regimes are fast, brutal and decisive in suppressing popular revolt (some of them even declining over decades to sign the fundamental Charter on HR). After all, the source of their legitimacy is an omnipresent and omnipotent apparatus of coercion (police, royal guard, army), not a democratically contested popular support in the multiparty scenery. Real democracies with the well-consolidated institutions, civil sector and matured political culture of electorate enjoy larger system legitimacy. -

Att Ratifications Applauded by the Prime Minister

SEPTEMBER 2014 ATT RATIFICATIONS APPLAUDED BY THE PRIME MINISTER The 50th ratication for the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) to enter into force was received at the United Nations on 25th September, 2014 when The Bahamas, Saint Lucia, Portugal, Senegal and Uruguay all ratied the treaty bringing the number of countries to 53. SEPTEMBER 2014 TABLE OF ATT RATIFICATION APPLAUDED BY THE CONTENTS PRIME MINISTER Pg 2 - ATT RATIFICATION APPLAUDED BY THE PRIME MINISTER Pg 3 - MINISTER DOOKERAN DESCRIBES TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO’S PARTICIPATION AT UNGA AS A SUCCESS - TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO SIGNS THE NATIONAL INDICATIVE PROGRAMME Pg 4 - TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO ADOPTS THE AOSIS LEADERS’ DECLARATION 2014 Prime Minister Kamla Persad-Bissessar delivers address at the General Debate of the - EUROPEAN FUNDING FOR TRINIDAD AND 69th Session of the United Nations General Assembly TOBAGO rime Minister Kamla Persad-Bissessar lauded the ratification of the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) by members of the regional and international communities as Pg 5 - EDUCATE THE YOUTH ON RESISTANCE a means of ensuring more peaceful resolution to international conflict. She AGAINST COLONIAL DOMINATION P said this “marked the achievement of another milestone for the international community and a triumph for multilateral diplomacy as the preferred means to Pg 6 - CULTURAL CONNECTIONS resolve the most serious problems confronting the international community.” The Pg 7 - P.S. PARILLON BEGINS HER NEW JOURNEY Prime Minister indicated that she was very pleased that among those States which ratified the Treaty were The Bahamas and St. Lucia bringing the total number of IN LIFE ratifications by CARICOM States to eight, with all fourteen having already signed Pg 8 - NATIONALS CELEBRATE REPUBLIC DAY the ATT. -

Water Insecurity and Sanitation in Asia

WATER INSECURITY AND SANITATION IN ASIA Edited by Naoyuki Yoshino, Eduardo Araral, and KE Seetha Ram ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK INSTITUTE PANTONE 281C WATER INSECURITY AND SANITATION IN ASIA Edited by Naoyuki Yoshino, Eduardo Araral, and KE Seetha Ram © 2019 Asian Development Bank Institute All rights reserved. First printed in 2019. ISBN 978–4–89974–113–8 (Print) ISBN 978–4–89974–114-5 (PDF) The views in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI), its Advisory Council, ADB’s Board or Governors, or the governments of ADB members. ADBI does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. ADBI uses proper ADB member names and abbreviations throughout and any variation or inaccuracy, including in citations and references, should be read as referring to the correct name. By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or by using the term “recognize,” “country,” or other geographical names in this publication, ADBI does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Users are restricted from reselling, redistributing, or creating derivative works without the express, written consent of ADBI. The Asian Development Bank recognizes “China” as the People’s Republic of China, "Korea" as the Republic of Korea, and "Vietnam" as Viet Nam. Note: In this publication, “$” refers to US dollars. Asian Development Bank Institute -

India After Independence

10 India After Independence A New and Divided Nation When India became independent in August 1947, it faced a series of very great challenges. As a result of Partition, 8 million refugees had come into the country from what was now Pakistan. These people had to be found homes and jobs. Then there was the problem of the princely states, almost 500 of them, each ruled by a maharaja or a nawab, each of whom had to be persuaded to join the new nation. The problems of the refugees and of the princely states had to be addressed immediately. In the longer term, the new nation had to adopt a political system that would best serve the hopes and expectations of its population. Fig. 11Fig. – Mahatma Gandhi's ashes being immersed in Allahabad, February 1948 Less than six months after independence the nation was in mourning. On 30 January 1948, Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated by a fanatic, Nathuram Godse, because he disagreed with Gandhiji’s conviction that Hindus and Muslims should live together in harmony. That evening, a stunned nation heard Jawaharlal Nehru’s moving statement over All India Radio: “Friends and comrades, the light has gone out of our lives and there is darkness everywhere … our beloved leader … the Father of the Nation is no more.” 128 OUR PASTS – III 2021-22 India’s population in 1947 was large, almost 345 Activity million. It was also divided. There were divisions Imagine that you are a between high castes and low castes, between the British administrator majority Hindu community and Indians who practised leaving India in 1947. -

HISTORY & GEOGRAPHY Time: 1 Hour

mauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritius mauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritius mauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritius mauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritius mauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritius mauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritius mauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritius mauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritius mauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritius mauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritius mauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritius mauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritius -

Contextual Background of the United Arab Emirates (UAE)

Chapter 2 Contextual Background of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) Dubai is a stirring alchemy of profound traditions and ambitious futuristic vision wrapped into starkly evocative desert splendour. Anonymous ∵ To fully understand the themes within the participants’ stories it is important to understand the context in which these took place. Foremost in the context is an understanding of the Islamic roots that underpin the participants’ world view. Islam is inextricably interwoven into the everyday life of Muslim women, playing a key role in how they construct their identities of self. The values of modesty, humility, service to others, credibility, caring for family and the daily practices and rituals of Islam underpin the participants’ stories. The span of time of participants’ stories covered the 1950s to the present. During that period the UAE went through some dramatic changes in education, the socioeconomic sector and governance. Prior to Federation in 1971 the current UAE comprised separate emirates and was known as the Trucial States. The population was centered either in larger coastal towns such as Dubai and Abu Dhabi or in smaller villages in the oases and mountain regions. Economic activity in the urban areas was mainly centered around agriculture, pearl diving, fishing and mercantile/trading activity. Social life was dominated by a tribal system with well structured social hierarchies and kinship structures. There was no formal education system prior to 1953 when the first boys’ school opened in Sharjah emirate but children (boys) from wealthy families were often sent abroad for their education. During this period local children were educated by ‘mutawa’a,’ respected local men and women who taught groups of children in their homes. -

How Do Non-Democratic Regimes Claim Legitimacy? Comparative Insights from Post-Soviet Countries

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics von Soest, Christian; Grauvogel, Julia Working Paper How Do Non-Democratic Regimes Claim Legitimacy? Comparative Insights from Post-Soviet Countries GIGA Working Papers, No. 277 Provided in Cooperation with: GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies Suggested Citation: von Soest, Christian; Grauvogel, Julia (2015) : How Do Non-Democratic Regimes Claim Legitimacy? Comparative Insights from Post-Soviet Countries, GIGA Working Papers, No. 277, German Institute of Global and Area Studies (GIGA), Hamburg This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/121908 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Inclusion of a paper in the Working Papers series does not constitute publication and should limit in any other venue. -

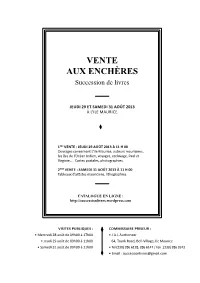

Vente Aux Enchères Succession De Livres

VENTE AUX ENCHÈRES Succession de livres JEUDI 29 ET SAMEDI 31 AOÛT 2013 À L’ILE MAURICE. 1ÈRE VENTE : JEUDI 29 AOÛT 2013 À 11 H 00 Ouvrages concernant L’Ile Maurice, auteurs mauriciens, les îles de l’Océan Indien, voyages, esclavage, Paul et Virginie,…. Cartes postales, photographies. 2EME VENTE : SAMEDI 31 AOÛT 2013 À 11 H 00 Tableaux d’artistes mauriciens, lithographies. CATALOGUE EN LIGNE : http://successionlivres.wordpress.com VISITES PUBLIQUES : COMMISSAIRE PRISEUR : • Mercredi 28 août de 09h00 à 17h00 • J.A.L Auctioneer • Jeudi 29 août de 09h00 à 11h00 64, Trunk Road, Bell-Village, Ile Maurice • Samedi 31 août de 09h00 à 11h00 • Tel (230) 286 6128, 286 6147 / Fax : (230) 286 2673 • Email : [email protected] Information Une vente aux enchères concernant la succession de livres de M. …, bibliophile d’ouvrages concernant L’Ile Maurice ou publiés à L’Ile Maurice, se tiendra à L’Ile Maurice : • 1ÈRE VENTE : JEUDI 29 AOÛT 2013 À 11 H 00 Ouvrages concernant L’Ile Maurice, auteurs mauriciens, les îles de l’Océan Indien, voyages, esclavage, Paul et Virginie,…. Cartes postales, photographies. •2EME VENTE : SAMEDI 31 AOÛT 2013 À 11 H 00 Tableaux d’artistes ayant vécu à Maurice, lithographies. - Le lieu de vente vous sera communiqué dans les meilleurs délais. Les ouvrages seront vendus par lots, organisés par thématiques (ex : histoire, esclavage, auteur, Madagascar, agriculture, religion,…). Un catalogue des lots est disponible en ligne à l’adresse suivante : http://successionlivres.wordpress.com où vous pouvez avoir accès à un moteur de recherche. Il est également téléchargeable en format pdf ici. -

Hansard and Circulate It, Because Members May Not Have the Appreciation of the Great Founder of the Party

1 Leave of Absence Friday, March 25, 2011 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Friday, March 25, 2011 The House met at 1.30 p.m. PRAYERS [MR. SPEAKER in the Chair] LEAVE OF ABSENCE Mr. Speaker: Hon. Members, the Hon. Winston Dookeran, Member for Tunapuna, is presently out of the country and has asked to be excused from sittings of the House during the period March 23rd, 2011 to April 1st, 2011. The Hon. Dr. Lincoln Douglas, Member of Parliament for Lopinot/Bon Air West is also out of the country and has asked to be excused from sittings of the House during the period March 23rd, 2011 to March 25th, 20011. The leave which the Members seek is granted. LETTER OF CONDOLENCE (JAPAN TRAGEDY) Mr. Speaker: Hon. Members, we were all shaken by the horrific events that took place in Japan on March 11, 2011. On behalf of this honourable House I have sent a letter to Mr. Takahiro Yokomichi, the Speaker of the House of the Representatives of Japan, expressing sentiments of sadness after the devastating earthquake and tsunami that swept the north-east of Japan on that tragic day. On your behalf, I conveyed condolences to the hon. Speaker and Members of the House of Representatives, as well as the people of Japan over the lost of so many precious lives. I offered our prayers that the resilience of the people of Japan, for which they are well recognized, will be strengthened as they strive to recover from this tragedy. PAPERS LAID 1. Report of the Auditor General of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago on the financial statements of the Couva-Tabaquite-Talparo Regional Corporation for the year ended September 30, 2005. -

Sheikh Mujibur Rehman: Founder of Bangladesh

Vol. 9(5), pp. 152-158, May 2015 DOI: 10.5897/AJPSIR2015.0771 Article Number: D0DBCF452758 African Journal of Political Science and ISSN 1996-0832 Copyright © 2015 International Relations Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/AJPSIR Review Sheikh Mujibur Rehman: Founder of Bangladesh Shahnawaz Mantoo Department of Political Science, University of Kashmir Hazratbal, Srinagar, Pin-190006. Received 2 February, 2015; Accepted 21 April, 2015 Charismatic leaders are the gifts and mercy from God. They are torch bearers of knowledge and revolution. Every nation in one way or the other has been and is endowed with leaders and same is the case of Bangladesh nation which was fortunate enough to have a leader like Sheikh Mujibur Rehman who guided them in the times of freedom struggle, and thrusted them into the region which dawned tranquility of mind and unshackled boundaries. It is in fact an old saying that good leaders build good nations which is equally true with the Bangladesh nation for which sheikh Mujibur Rehman sacrificed every breath and blood of his life and mapped a new nation in the world. In this paper, the author tried to highlight the personal life of Sheik Mujib and the main focus of the paper is to emphasize the political life of the leader. The paper discusses the main achievements of the leader and particularly the independence of Bangladesh of which Mujib was the pivotal figure. Key words: Mujib, Bangladesh, leadership, freedom, struggle, democracy. INTRODUCTION Father of the Nation is an honorific bestowed on Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman is the architect of individuals who are considered the most important in the Bangladesh country by all implications of the term. -

Mauritius and the Netherlands: Current Linkages and the Heritage of Connections

African Studies Centre Leiden The Netherlands Mauritius and the Netherlands: Current linkages and the heritage of connections Ton Dietz (African Studies Centre Leiden) ASC Working Paper 144 / 2018 African Studies Centre Leiden P.O. Box 9555 2300 RB Leiden The Netherlands Telephone +31-71-5273372 Website www.ascleiden.nl E-mail [email protected] © Ton Dietz ([email protected]) Mauritius and the Netherlands: current linkages and the heritage of connections Ton Dietz (African Studies Centre Leiden)1 Current linkages For a country bearing a name that refers to the Netherlands, the current linkages with the Netherlands are quite limited. Mauritius is named after a Dutch political hero: Prince Maurits of Nassau, stadholder of Holland and Zealand between 1585 and 16252, and the son and successor of the ‘Father of the Nation’, William of Orange after he was murdered in 1584. Maurits successfully led the revolt (‘opstand’) against Spain, the former ruler of the Netherlands. The island received its name ‘Mauritius’ (or earlier spelt as “‘t Eylant Mauwerijcye de Nassau”; Moree, 2012) in 1595. During that year Maurits was twenty-eight years old. Figures 1, 2 and 3: Maurits of Nassau in 1588, in 1607 and in 16143, and Figure 4: Maurits on a Mauritian postage stamp celebrating the 400th anniversary of Dutch landing 1598-19984. 1 Emeritus professor of African Development at the University of Leiden and former director of the African Studies Centre Leiden; [email protected]; earlier publication about Mauritius: Norder et al., 2012. 2 In 1590 he also became stadholder of Utrecht, Gelre and Overijssel, and in 1620 of Groningen and Drenthe.