Oral Histories: a Traditional Choreographic Approach to Autobiographical Themes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Conowingo Tunnel and the Anthracite Mine Flood-Control Project a Historical Perspective on a “Solution” to the Anthracite Mine Drainage Problem

The Conowingo Tunnel and the Anthracite Mine Flood-Control Project A Historical Perspective on a “Solution” to the Anthracite Mine Drainage Problem Michael C. Korb, P.E. Environmental Program Manager Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection Bureau of Abandoned Mine Reclamation (BAMR) Wilkes Barre District Office [email protected] www.depweb.state.pa.us Abstract Fifty-seven years ago, Pennsylvania’s Anthracite Mine Drainage Commission recommended that the Conowingo Tunnel, an expensive, long-range solution to the Anthracite Mine Drainage problem, be “tabled” and that a cheaper, short-range “job- stimulus” project be implemented instead. Today Pennsylvania’s anthracite region has more than 40 major mine water discharges, which have a combined average flow of more than 285,000 gallons per minute (GPM). Two of these average more than 30,000 GPM, 10 more of the discharges are greater than 6,000 GPM, while another 15 average more than 1,000 GPM. Had the Conowingo Tunnel Project been completed, most of this Pennsylvania Anthracite mine water problem would have been Maryland’s mine water problem. Between 1944 and 1954, engineers of the US Bureau of Mines carried out a comprehensive study resulting in more than 25 publications on all aspects of the mine water problem. The engineering study resulted in a recommendation of a fantastic and impressive plan to allow the gravity drainage of most of the Pennsylvania anthracite mines into the estuary of the Susquehanna River, below Conowingo, Maryland, by driving a 137-mile main tunnel with several laterals into the four separate anthracite fields. The $280 million (1954 dollars) scheme was not executed, but rather a $17 million program of pump installations, ditch installation, stream bed improvement and targeted strip-pit backfilling was initiated. -

Eliot Feld Ballet Schedules Three Concerts the Feld Ballet, Which Will Close out Its Highly Successful New York Season Oct

William and Mary NEWS Volume XI, Number 7 ' Noii-Profit Organization Tuesday, October 19,1982 U.S. Postage PAID at WflliaaMburg, Va. Permit No. 26 College to Honor Six Alumni at Homecoming Six members of the Society of the member and former secretary of the Alumni will receive the Alumni Medallion President's Council and a member of the at Homecoming on Nov. 5-6 in recogni¬ Lord Chamberlain Society of the Virginia tion of their service to the College, Shakespeare Festival. In 1976, she and community and nation. her husband established the Sheridan- The recipients are Dr. Edward E. Kinnamon Scholarship at the College. Brickell, Jr. '50, former rector of the Muscarelle, who is chairman of the College and superintendent of Virginia board of one of the nation's largest Beach, Va. Schools; Chester F. Giermak building firms, has been honored many '50, Erie, Pa.; president and chief execu¬ times for his charitable and civic contribu¬ tive officer, Eriez Magnetics Company; tions which include the Joseph L. Mus1- Jeanne S. Kinnamon '39, Williamsburg, a carelle Center for Building Construction member of the Board of Visitors and a Studies at Farleigh Dickinson University in generous benefactor of the College; New Jersey. Among his awards is the Joseph L. Muscarelle '27, Hackensack, Pope John Paul II Humanitarian Award N.J., chairman of the Board of Joseph L. from Seton Hall University. Muscarelle has Muscarelle, Inc., and the prime benefactor been a member of the Order of the White of the Joseph L. and Margaret Muscarelle Jacket since 1977. Museum of Art now under construction at Dr. -

Kingdom of the Monarchs Mexico Tour

For More Information Contact See More Tours at Cynthia Marion - 214.497.4074 www.travelphiletours.com KINGDOM OF THE MONARCHS MEXICO TOUR Benefiting Wimberley’s EmilyAnn Theatre & Gardens Friday February 9-Thursday February 15, 2018 7 Days / 6 Nights LEAVING FROM WIMBERLEY Enjoy our exciting ecological and cultural adventure. Fall in love with the Monarchs as you spend 2 days including Valentines day with tens of millions of Monarch butterflies! Experience one of the world’s most astounding natural events featuring the delicate Monarch at two different sanc- tuaries in Mexico where they “winterize” prior to making a remarkable springtime 3,000 mile journey to the northeastern US and Canada. Along the way we’ll take a boat ride with a local birding expert through floating gardens and canals of Xochimilco and explore Coyoacán, one of the most well preserved colonial areas of Mexico City to experience the art and culture of artists Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. Day 1 Texas to Mexico City Friday February 9 Depart Texas for Mexico City and the wonders that await. Upon arrival, we’ll transfer to our 4 ½ Star Tripadvisor rated hotel where you’ll have free time to get settled in your hotel room. We gather this evening for a welcome dinner at the award-winning Taberna del Leon. (D) Hotel: Paraiso See More Tours at For More Information Contact www.travelphiletours.com Cynthia Marion - 214.497.4074 Day 2 Mexico City Saturday February 10 Breakfast. Leave for one of the best handicrafts market in all of Mexico, Bazaar Del Sabado in San Angel. -

Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still Calling Her Q!

1 More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In InfiniteBody art and creative consciousness by Eva Yaa Asantewaa Tuesday, May 6, 2014 Your Host Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still calling her Q! Eva Yaa Asantewaa Follow View my complete profile My Pages Home About Eva Yaa Asantewaa Getting to know Eva (interview) Qurrat Ann Kadwani Eva's Tarot site (photo Bolti Studios) Interview on Tarot Talk Contact Eva Name Email * Message * Send Contribute to InfiniteBody Subscribe to IB's feed Click to subscribe to InfiniteBody RSS Get InfiniteBody by Email Talented and personable Qurrat Ann Kadwani (whose solo show, They Call Me Q!, I wrote about Email address... Submit here) is back and, I hope, every bit as "wicked smart and genuinely funny" as I observed back in September. Now she's bringing the show to the Off Broadway St. Luke's Theatre , May 19-June 4, Mondays at 7pm and Wednesdays at 8pm. THEY CALL ME Q is the story of an Indian girl growing up in the Boogie Down Bronx who gracefully seeks balance between the cultural pressures brought forth by her traditional InfiniteBody Archive parents and wanting acceptance into her new culture. Along the journey, Qurrat Ann Kadwani transforms into 13 characters that have shaped her life including her parents, ► 2015 (222) Caucasian teachers, Puerto Rican classmates, and African-American friends. Laden with ▼ 2014 (648) heart and abundant humor, THEY CALL ME Q speaks to the universal search for identity ► December (55) experienced by immigrants of all nationalities. ► November (55) Program, schedule and ticket information ► October (56) ► September (42) St. -

Sistema De Memoria Colectiva En El Metro Imagotipos En La Ciudad De México*

INVESTIGACIÓN 9 Sistema de memoria colectiva en el Metro Imagotipos en la Ciudad de México* Francisco López Ruiz Resumen El Sistema de Transporte Metropolitano (Metro) de la Ciudad de México ofrece un valor simbólico único en el mundo. Desde hace cuatro décadas las estaciones del Metro son representadas mediante íconos o imagotipos. El objetivo de este artículo es contrastar las características gráficas de dos imagotipos y la vinculación con su contexto urbano e histórico: los ideogramas de las estaciones La Noria (tren ligero) y Cuatro Caminos (línea 2 del Metro). El argumento central establece que los imagotipos del Metro y otros sistemas de transporte capitalino forman parte de la riqueza patri- monial y la identidad de la Ciudad de México, ya que simbolizan de manera creativa diversos elementos culturales y urbanos. Abstract Mexico City’s subway icons are unique examples of urban graphic design. The purpose of this essay is to compare two icons –La Noria (urban train) and Cuatro Caminos (subway)– and analyze their historical and cultural meaning or significance. The main argument is that such subway icons stand as symbols of Mexico City’s cultural heritage insofar they represent diverse cultural and urban elements. * Esta investigación pertenece al proyecto Energía y arquitectura sustentable, financiado por la Dirección de Investigación de la, Universidad Iberoamericana, Ciudad de México y el Patronato Económico de la misma universidad (FICSAC). 10 Francisco López Ruiz arquitectos, con lo cual se evita la fealdad El ingeniero Bernardo -

Focus on Art: the Spirit of Frida

focus on art: the spirit of frida Experience the sights, sounds, tastes and art that influenced a woman who challenged the world of art and polite society, Frida Kahlo. April 18 – 25 2017 or April 18-28, 2017 extension option trip details Travel with Hank & Laura Hine to Mexico to explore the world of Frida Kahlo, her art, and her tumultuous life with husband, partner and obsession Diego Rivera. Mexico City San Miguel de Highlights Allende Highlights Welcome dinner at Trolley touring Restaurant Café Tacuba Walking tour of galleries National Folkloric and shopping at Ballet performance Fábrica La Aurora Frida’s Casa Azul Guided visit to ‘the Sistine Chapel of the Americas’ The House Museum of Dolores Olmedo Folk art museum Soumaya Museum Special farewell dinner Guided visits to Rivera’s works Fine dining throughout Xilitla and Guanajuato Optional Extension Highlights Tour through spectacular Sierra Gorda; 2 nights in the El Castillo and La Posada de James; Edward James’ jungle sculpture garden; bath, waterfall and natural pools of Las Pozas; Diego Rivera’s house and museum; soiree with troubadours. Cost: $4,694* per person, double occupancy; single travelers add $1,069 Optional 4-day/3-night Extension add $1,259 per person double occupancy, single travelers add $350 more *Your price includes a $500 per person tax-deductible honorarium to The Dalí Museum. Details to follow. A deposit of $500 per person, a and membership with The Dalí Museum, are required to hold your space. Final payment is due January 18, 2017 price includes Main program: -

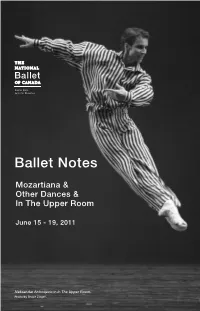

Ballet Notes

Ballet Notes Mozartiana & Other Dances & In The Upper Room June 15 - 19, 2011 Aleksandar Antonijevic in In The Upper Room. Photo by Bruce Zinger. Orchestra Violins Bassoons Benjamin BoWman Stephen Mosher, Principal Concertmaster JerrY Robinson LYnn KUo, EliZabeth GoWen, Assistant Concertmaster Contra Bassoon DominiqUe Laplante, Horns Principal Second Violin Celia Franca, C.C., Founder GarY Pattison, Principal James AYlesWorth Vincent Barbee Jennie Baccante George Crum, Music Director Emeritus Derek Conrod Csaba KocZó Scott WeVers Karen Kain, C.C. Kevin Garland Sheldon Grabke Artistic Director Executive Director Xiao Grabke Trumpets David Briskin Rex Harrington, O.C. NancY KershaW Richard Sandals, Principal Music Director and Artist-in-Residence Sonia Klimasko-LeheniUk Mark Dharmaratnam Principal Conductor YakoV Lerner Rob WeYmoUth Magdalena Popa Lindsay Fischer JaYne Maddison Trombones Principal Artistic Coach Artistic Director, Ron Mah DaVid Archer, Principal YOU dance / Ballet Master AYa MiYagaWa Robert FergUson WendY Rogers Peter Ottmann Mandy-Jayne DaVid Pell, Bass Trombone Filip TomoV Senior Ballet Master Richardson Tuba Senior Ballet Mistress Joanna ZabroWarna PaUl ZeVenhUiZen Sasha Johnson Aleksandar AntonijeVic, GUillaUme Côté*, Violas Harp Greta Hodgkinson, Jiˇrí Jelinek, LUcie Parent, Principal Zdenek KonValina, Heather Ogden, Angela RUdden, Principal Sonia RodrigUeZ, Piotr StancZYk, Xiao Nan YU, Theresa RUdolph KocZó, Timpany Bridgett Zehr Assistant Principal Michael PerrY, Principal Valerie KUinka Kevin D. Bowles, Lorna Geddes, -

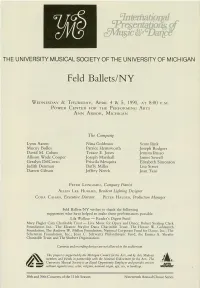

Feld Ballets/NY

THE UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Feld Ballets/NY WEDNESDAY & THURSDAY, APRIL 4 & 5, 1990, AT 8:00 P.M. POWER CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN The Company Lynn Aaron Nina Goldman Scott Rink Mucuy Bolles Patrice Hemsworth Joseph Rodgers David M. Cohen Terace E. Jones Jennita Russo Allison Wade Cooper Joseph Marshall James Sewell Geralyn DelCorso Priscila Mesquita Elizabeth Simonson Judith Denman Buffy Miller Lisa Street Darren Gibson Jeffrey Neeck Joan Tsao PETER LONGIARU, Company Pianist ALLEN LEE HUGHES, Resident Lighting Designer CORA CAHAN, Executive Director PETER HAUSER, Production Manager Feld Ballets/NY wishes to thank the following supporters who have helped to make these performances possible: Lila Wallace Reader's Digest Fund Mary Flagler Gary Charitable Trust Live Music for Opera and Dance; Robert Sterling Clark Foundation Inc.; The Eleanor Naylor Dana Charitable Trust; The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation; The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation; National Corporate Fund for Dance, Inc.; The Scherman Foundation, Inc.; Joan C. Schwartz Philanthropic Fund; the Emma A. Sheafer Charitable Trust; and The Shubert Organization. Cameras and recording devices are not allowed in the auditorium. This project is supported by the Michigan Council for the Arts, and by Arts Midwest members and friends in partnership with the National Endowment for the Arts. The University Musical Society is an Equal Opportunity Employer and provides services without regard to race, color, religion, national origin, age, sex, or handicap. 38th and 39th Concerts of the lllth Season Nineteenth Annual Choice Series PROGRAM Wednesday, April 4 CONTRA POSE (1990) Choreography: Eliot Feld Music: C. -

The Boston Conservatory Dance Ensemblepresents “Spring Works,” Free Performances April 13 and 14

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT : Joyce Linehan 617-282-2510 x 1, [email protected] THE BOSTON CONSERVATORY DANCE ENSEMBLEPRESENTS “SPRING WORKS,” FREE PERFORMANCES APRIL 13 AND 14 High res images of previous Boston Conservatory Dance productions available on request (BOSTON—April 5, 2012) The Boston Conservatory Dance Ensemble presents Spring Works, a varied program featuring original choreography by students of the Dance Division and new works by Lorraine Chapman and Anna Myer. Performances take place Friday and Saturday, April 13 and 14 at 8 p.m. at The Boston Conservatory Theater, 31 Hemenway Street, in Boston’s Fenway neighborhood. Admission is FREE . For more information, call The Boston Conservatory event line at (617) 912-9240 or visit www.bostonconservatory.edu /perform. PROGRAM Breakdown of the Over-Educated (premiere) Choreography by Marlie Couto.Original composition by Max Judelson. Do You Have Any Space for My Valuables? (premiere) Choreography by Shannon McColl. Original composition by Kenny Rosenberg. Excerpts from All at Once (2004) Choreography by Anna Myer. Music by Jakov Jakoulov. Preventing Scurvy (premiere) Choreography by David Glista. Original composition by Will Piquette and Aaron Freid. I Think I Want a Divorce (premiere) Choreography by Elizabeth Cappabianca. Original composition by Forrest Gray. Within the Palm (premiere) Choreography by Coree McKee. Original composition by Joffrey Gaetz III. Flirting with Subtext (premiere) Choreography by Margot Gelber. Original composition by Evan Racynski. How ‘bout Now? (premiere) Choreography by Gina dePool. Original composition by Edgar dePool Jr. Sleeping on the Ceiling (premiere) Choreography by Margaret Foster. Original composition by Ethan Parcell. The Changing Room (premiere) Choreography by Lorraine Chapman. -

Mexico City and San Miguel De Allende SCHEDULE BY

An Art Lover’s Mexico: Mexico City and San Miguel de Allende October 19-26, 2018 Immerse yourself in the art, architecture, and cuisine of Mexico on this tour of Mexico City and San Miguel de Allende. Begin in Mexico City’s colonial center, touring the city's spectacular murals and dramatic architecture. Enjoy traditional home cooking at the Casa Pedregal, designed by notable Mexican architect Luis Barragán. See the Torres de Ciudad Satélite, an iconic piece of modern sculpture and architecture. In San Miguel de Allende, meander along narrow cobblestone streets, and view colorful arcades and courtyards, rustic houses, and elegant mansions. Conclude with a visit to El Charco del Ingenio botanical gardens to see migrating birds, serene waterfalls, and lush landscapes. GROUP SIZE: From 16 to 30 travelers PRICING: $4,995 per person double occupancy / Single supplement: $1,295 STUDY LEADER: JEFFREY QUILTER is the William and Muriel Seabury Howells Director of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology and senior lecturer in anthropology at Harvard. Trained as an anthropological archaeologist, Jeffrey has focused much of his career on the early societies of Peru. Recently, his interest in issues of the origins and nature of complex societies has shifted to a focus on viewing social and environmental changes over long periods of time. ____________________________________________________________________________________________ luxurious hotel, located near Chapultepec SCHEDULE BY DAY Park. B=Breakfast, L=Lunch, D=Dinner, R=Reception After checking into your hotel, drive to the National Museum of Anthropology to see FRIDAY, OCTOBER 19 exquisite sculptures and artifacts from ARRIVE MEXICO CITY Mexico’s pre-Columbian civilizations. -

Jeffrey Stanton Release

MEDIA RELEASE OBT to round out its artistic team with a second ballet master, Jeffrey Stanton. July 15, 2013 - Portland, OR Jeffrey Stanton, former principal dancer with Pacific Northwest Ballet (1994-2011) and currently a faculty memBer at the PNB School will Be joining Oregon Ballet Theatre as Ballet master, alongside Rehearsal Director Lisa Kipp. He will arrive in August. “I think Jeffrey and Lisa’s skills complement each other well and I am excited for the dancers to have a chance to work with both of them in the studio” shared Artistic Director Kevin Irving. About Jeffrey Stanton Mr. Stanton trained at San Francisco Ballet School and the School of American Ballet. In addition to classical Ballet, he also studied Ballroom, jazz, and tap dancing. He joined San Francisco Ballet in 1989 and left to join Pacific Northwest Ballet as a memBer of the corps de Ballet in 1994. He was promoted to soloist in 1995 and was made a principal in 1996. “Jeff has Been a Brilliant dancer, great colleague and stalwart Company memBer for seventeen years – a lifetime in dance and a gift to his artistic directors. It is our hope that, when he retires from performing, he will pass on everything he knows to future generations of young dancers,” shared PNB Founding Artistic Directors Kent Stowell and Francia Russell, (who hired Mr. Stanton in 1994) upon his retirement in 2011. He originated leading roles in Susan Stroman’s TAKE FIVE…More or Less; Stephen Baynes' El Tango; Donald Byrd's Seven Deadly Sins; Val Caniparoli's The Bridge; Nicolo Fonte's Almost Tango and Within/Without; Kevin O'Day's Aract and [soundaroun(d)ance]; Kent Stowell's Carmen, Palacios Dances, and Silver Lining; and Christopher Stowell's Zaïs. -

Rediseño Del Manual De Capacitación Para Guías Temporales Del Museo Dolores Olmedo

UNIVERSIDAD PEDAGÓGICA NACIONAL Unidad Ajusco Licenciatura en Psicología Educativa Informe de intervención profesional Rediseño del manual de capacitación para guías temporales del Museo Dolores Olmedo Tesis Que para obtener el título de Licenciado en Psicología Educativa Presenta: Luis Antonio Jimenez Velazquez Asesora Dra. Mónica García Hernández Ciudad de México 2017 Agradecimientos A mis padres Teresa Velazquez y Luis Jimenez: Por todo el esfuerzo, paciencia y apoyo que me han brindado, sé que no he sido un hijo ejemplar pero gracias a sus consejos pude concluir esta etapa de mi vida. A Evelin y Leonardo: Hermana, sé que no siempre nos llevamos bien, pero te agradezco todo lo que haces por mí, es divertido compartir la vida contigo. Leo, espero siempre tengas una vida interesante en todo aspecto, goza, disfruta y se feliz creciendo. Los amo. A Jacinta López y Antonio Badillo y a sus hijos Karina, Celene, Gloria, Ivonne y Marcos: Porque son parte de mi familia nuclear y siempre han estado al pendiente de mí en todo aspecto de la vida. Gracias, pocas personas tienen la dicha de rodearse de tan buenas personas. A mi familia de Guanajuato: Son el perfecto escape de la rutina de esta ciudad. Los quiero. A Karen: ¿Quién pensaría que una obra de mi infancia, que comprendí años después, resultaría un punto de encuentro para ambos? (Le Petit Prince). A lo largo de estos años te has convertido en una pieza esencial de mi vida, te has vuelto parte de mi familia y más, gracias por estar a mi lado. A la Doctora Mónica García Hernández: Por apoyarme y guiarme en la elaboración de este proyecto.