An Incomplete Project: Modernism, Formalism and the 'Music Itself'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philosophy in the Artworld: Some Recent Theories of Contemporary Art

philosophies Article Philosophy in the Artworld: Some Recent Theories of Contemporary Art Terry Smith Department of the History of Art and Architecture, the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA; [email protected] Received: 17 June 2019; Accepted: 8 July 2019; Published: 12 July 2019 Abstract: “The contemporary” is a phrase in frequent use in artworld discourse as a placeholder term for broader, world-picturing concepts such as “the contemporary condition” or “contemporaneity”. Brief references to key texts by philosophers such as Giorgio Agamben, Jacques Rancière, and Peter Osborne often tend to suffice as indicating the outer limits of theoretical discussion. In an attempt to add some depth to the discourse, this paper outlines my approach to these questions, then explores in some detail what these three theorists have had to say in recent years about contemporaneity in general and contemporary art in particular, and about the links between both. It also examines key essays by Jean-Luc Nancy, Néstor García Canclini, as well as the artist-theorist Jean-Phillipe Antoine, each of whom have contributed significantly to these debates. The analysis moves from Agamben’s poetic evocation of “contemporariness” as a Nietzschean experience of “untimeliness” in relation to one’s times, through Nancy’s emphasis on art’s constant recursion to its origins, Rancière’s attribution of dissensus to the current regime of art, Osborne’s insistence on contemporary art’s “post-conceptual” character, to Canclini’s preference for a “post-autonomous” art, which captures the world at the point of its coming into being. I conclude by echoing Antoine’s call for artists and others to think historically, to “knit together a specific variety of times”, a task that is especially pressing when presentist immanence strives to encompasses everything. -

Formalism Post- Formalism

FORMALISM POST- FORMALISM nonsite.org is an online, open access, peer-reviewed quarterly journal of scholarship in the arts and humanities 7 affiliated with Emory College of Arts and Sciences. 2014 all rights reserved. ISSN 2164-1668 EDITORIAL BOARD Bridget Alsdorf Ruth Leys James Welling Jennifer Ashton Walter Benn Michaels Todd Cronan Charles Palermo Lisa Chinn, editorial assistant Rachael DeLue Robert Pippin Michael Fried Adolph Reed, Jr. Oren Izenberg Victoria H.F. Scott Brian Kane Kenneth Warren SUBMISSIONS ARTICLES: SUBMISSION PROCEDURE Please direct all Letters to the Editors, Comments on Articles and Posts, Questions about Submissions to [email protected]. Potential contributors should send submissions electronically via nonsite.submishmash.com/Submit. Applicants for the B-Side Modernism/Danowski Library Fellowship should consult the full proposal guidelines before submitting their applications directly to the nonsite.org submission manager. Please include a title page with the author’s name, title and current affiliation, plus an up-to-date e-mail address to which edited text and correspondence will be sent. Please also provide an abstract of 100-150 words and up to five keywords or tags for searching online (preferably not words already used in the title). Please do not submit a manuscript that is under consideration elsewhere. 1 ARTICLES: MANUSCRIPT FORMAT Accepted essays should be submitted as Microsoft Word documents (either .doc or .rtf), although .pdf documents are acceptable for initial submissions.. Double-space manuscripts throughout; include page numbers and one-inch margins. All notes should be formatted as endnotes. Style and format should be consistent with The Chicago Manual of Style, 15th ed. -

Conceptual Art: a Critical Anthology

Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology Alexander Alberro Blake Stimson, Editors The MIT Press conceptual art conceptual art: a critical anthology edited by alexander alberro and blake stimson the MIT press • cambridge, massachusetts • london, england ᭧1999 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval)without permission in writing from the publisher. This book was set in Adobe Garamond and Trade Gothic by Graphic Composition, Inc. and was printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Conceptual art : a critical anthology / edited by Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-262-01173-5 (hc : alk. paper) 1. Conceptual art. I. Alberro, Alexander. II. Stimson, Blake. N6494.C63C597 1999 700—dc21 98-52388 CIP contents ILLUSTRATIONS xii PREFACE xiv Alexander Alberro, Reconsidering Conceptual Art, 1966–1977 xvi Blake Stimson, The Promise of Conceptual Art xxxviii I 1966–1967 Eduardo Costa, Rau´ l Escari, Roberto Jacoby, A Media Art (Manifesto) 2 Christine Kozlov, Compositions for Audio Structures 6 He´lio Oiticica, Position and Program 8 Sol LeWitt, Paragraphs on Conceptual Art 12 Sigmund Bode, Excerpt from Placement as Language (1928) 18 Mel Bochner, The Serial Attitude 22 Daniel Buren, Olivier Mosset, Michel Parmentier, Niele Toroni, Statement 28 Michel Claura, Buren, Mosset, Toroni or Anybody 30 Michael Baldwin, Remarks on Air-Conditioning: An Extravaganza of Blandness 32 Adrian Piper, A Defense of the “Conceptual” Process in Art 36 He´lio Oiticica, General Scheme of the New Objectivity 40 II 1968 Lucy R. -

Art and Form: from Roger Fry to Global Modernism by Sam Rose.’ Estetika: the European Journal of Aesthetics LVII/XIII, ESTETIKA No

Gal, Michalle. ‘Art and Form: From Roger Fry to Global Modernism by Sam Rose.’ Estetika: The European Journal of Aesthetics LVII/XIII, ESTETIKA no. 2 (2020): pp. 183–188. DOI: https://doi.org/10.33134/eeja.223 THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF AESTHETICS BOOK REVIEW Art and Form: From Roger Fry to Global Modernism by Sam Rose Michalle Gal Shenkar College, IL [email protected] A book review of Sam Rose, Art and Form: From Roger Fry to Global Modernism. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2019. 208 pp. ISBN 9780271082387. In view of the current progress of what has been named the ‘visual turn’ or the ‘pictorial turn’,1 it is exciting to witness Sam Rose’s return to early aesthetic formalist-modernism, which was so passionate about the medium, its appearance, and visuality. Rose’s project shares a recent inclination to think anew the advent of aesthetic modernism.2 It is founded on the presump- tion that visual art ought to be – and actually has always been – theoretically subsumed under one meta-project. This meta-project does not necessarily have a clear telos, but it does have a history. In support of this view, Rose appeals to Stanley Cavell’s claim that ‘only mas- ters of a game, perfect slaves to that project, are in a position to establish conventions which better serve its essence. This is why deep revolutionary changes can result from attempts to conserve a project, to take it back to its idea, keep it in touch with its history’ (p. 155). According to Rose’s post-formalist view, the idea of art’s meta-project is the idea of form. -

01 Titlepage

Systems, Contexts, Relations: An Alternative Genealogy of Conceptual Art A thesis submitted to Middlesex University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Luke Skrebowski Centre for Research in Modern European Philosophy/History of Art and Design Middlesex University September 2009 Acknowledgments I would like to thank the following people: Professor Peter Osborne; Professor Jon Bird; the staff and students of the Centre for Research in Modern European Philosophy, Middlesex University; Hans Haacke; Mel Bochner; Chris and Jane Skrebowski; Suzi Winstanley. The research and writing of this thesis were supported by an AHRC Doctoral Award and a Gabriel Parker Travel Bursary from Middlesex University. i Abstract Recent scholarship has revisited conceptual art in light of its ongoing influence on contemporary art, arguing against earlier accounts of the practice which gave a restricted account of its scope and stressed its historical foreclosure. Yet conceptual art remains both historically and theoretically underspecified, its multiple and often conflicting genealogies have not all been convincingly traced. This thesis argues for the importance of a systems genealogy of conceptual art—culminating in a distinctive mode of systematic conceptual art—as a primary determinant of the conceptual genealogy of contemporary art. It claims that from the perspective of post-postmodern, relational and context art, the contemporary significance of conceptual art can best be understood in light of its “systematic” mode. The distinctiveness of contemporary art, and the problems associated with its uncertain critical character, have to be understood in relation to the unresolved problems raised by conceptual art and the implications that these have held for art’s post-conceptual trajectory. -

Download Bachelor of Art Theory Schema

1 SEEKING PHILOSOPHY BY WORDS 1 ART and META-ART ULRICH DE BALBIAN META-PHILOPHY RESEARCH CENTER 1 2 PREFACE The first encounter I had with her caused me to be passionate about her many levels, multi-dimensions, infinite contexts and endless questions I had about you. It was not merely a passing infatuation but instead the beginning of a long and ever deepening friendship, the repeated re-discovery of a long lost one, a profound bond. A bond with that what is my deepest being, an ever-increasing intimacy that always increases and multiplies, the fulfilment of a need, that what defines me, that what constitutes my reality, my life-worlds and the meaning of my multiverses. You are never out of my mind, you I seek in every context, you I need to find in all situations, from the seemingly most superficial, the everyday, the most subtle and simple, the most complex and cryptic. I perceive with and through you and see and think through you, you are the aims, the purpose and the contents of all my thought and reflections, you I seek endlessly, you I discover, uncover, find and encounter whatever hear, see, taste, touch and feel. You are the behind the energy of lover, the vibrations of lovers, the light of the stars, the source, both the beginning, the path leading to and the end and realization of wisdom. You are the shrine in which a deity reveals hidden knowledge and the divine purpose of life, you are the deity, the knowledge, the meaning and the purpose that are revealed. -

Notes on Queer Formalism by William J

Notes on Queer Formalism By William J. Simmons In a recent conversation with Amy Sillman at the opening of Leidy Churchman’s provocative solo show, Lazy River, at the Boston University Art Gallery, I asked Sillman about the state of painting. In 2011, Artforum considered the "The Ab-Ex Effect," thereby attempting to take the pulse of a simultaneously revered and reviled hallmark of modernism in the visual arts. Where had painting come since then? It was a question that had plagued me ever since my first encounter with Nicole Eisenman’s paintings, prints, and sculptures.1 Eisenman’s investment in art history, when combined with her penchant for absurdity and subversion, seemed to upend everything I knew about contemporary art. The same shock occurred when I thought about Sillman and her inscrutable mixture of pigment and perversion— and iPhones. With Amy Sillman: one lump or two opening at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, Boston, and Nicole Eisenman appearing in both the 2013 Carnegie International and Nicole Eisenman: In Love with My Nemesis at the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis in 2014, it seems that we are on the verge of a new definition of artistic practice. I had attempted for a while to characterize this charged moment, but it was not until Sillman answered, "It’s almost a queer formalism" that I found the necessary words.2 The phrase captures something revolutionary, a sense of palpable anticipation for much-needed transition that is just around the corner. The move toward queer formalism prefigured by Sillman and Eisenman, as well as artists Elise Adibi and Leidy Churchman, cannot be fully explained in a single article or with one analytical lens. -

Painting in the Expanded Field

COLOUR, SPACE, COMPOSITION: PAINTING IN THE EXPANDED FIELD Doctorate of Philosophy FRANCESCA MATARAGA 2012 College of Fine Arts University of New South Wales Acknowledgements Thank you to: Dr Susan Best and Nicole Ellis for their supervision, guidance and support, Dr Dominic Fitzsimmons and Associate Professor Sue Starfield from the UNSW Learning Centre, Joanna Elliot – Research Coordinator at COFA, the Projeto Hélio Oiticica for their generosity in providing a complete digital archive, Patricia Rosewall for her help with editing, and Catherine Johnson whose unfailing enthusiasm, optimism and support makes everything possible. ‘Material, space and colour are the main aspects of visual art’ Donald Judd1 1 Donald Judd, “Some aspects of color in general and red and black in particular”, Donald Judd Colorist, D. Elger (ed.), Thames & Hudson, London and Cantz, Ostfildern-Ruit, 1999, p. 79. CONTENTS Abstract Acknowledgements List of figures Introduction 11 1 Hélio Oiticica: Colour and Painting in Motion 25 2 Daniel Buren: Painting, Sculpture and Architecture 70 3 Jessica Stockholder: Painting in Space 109 Conclusion 152 Appendix 168 Bibliography 213 vi LIST OF FIGURES 1 Hélio Oiticica, Beyond Space (7th Havana Biennal), 2000/2001 25 2 Hélio Oiticica, Parangolés P25 Cape 21 ‘Xoxoba’, 1968 P08 Cape 05 ‘Mangueira’, 1965 P05 Cape 02, 1965 and P04 Cape 01, 1964 29 3 Hélio Oiticica, Parangolés P25 Cape 21 ‘Xoxoba’, 1968 P08 Cape 05 ‘Mangueira’, 1965 P05 Cape 02, 1965 and P04 Cape 01, 1964 29 4 Hélio Oiticica, Sêco 22, 1956 38 5 Hélio Oiticica, Metaesquema No.179, 1957 38 6 Hélio Oiticica, Parangolés Cape 01 and Cape 02, 1964/1965 39 7 Hélio Oiticica, Parangolé (with Miro de Mangueira), 1964/1965 39 8 Kasimir Malevich, Suprematist Composition: White on White, 1918 43 9 Hélio Oiticica, Bilateral Classico, 1959 43 10 Hélio Oiticica, Bilateral Teman, 1959 44 11 Hélio Oiticica, Bilateral Equali, 1959 45 12 Hélio Oiticica, Maquette for Spatial Relief No. -

REFLECTIONS of MINIMALISM on CONTEMPORARY CERAMICS

Volume: 4, Issue: 9, November-December/ 2019 Cilt: 4, Sayı: 9, Kasım-Aralık / 2019 REFLECTIONS of MINIMALISM ON CONTEMPORARY CERAMICS Kemal TİZGÖL* Abstract Minimalism appeared in the late ‘60s in United States and deeply affected art environment in this period. Besides, it has an important place in the art history as the latest effective attack of Modernist movements. After Second World War, art was influenced by fundamental revolutions in social structure, thus Minimalism takes place in the art area as an alternative attitude against to Abstract Expressionist movement. At first, Minimalism was strongly criticized and resisted but later accepted by the critics and audience. During Modernism, ceramics is freed from its traditional roots and has a contemporary appearance with its own special qualities both formally and conceptually. Ceramics and Minimalism appear to be two separate and alien phenomena, which at first glance are temporary; their relations with each other are not perceived at once. This impression also carries a margin of reality. This study aims to investigate Minimalism in the historical context and its reflections on the Contemporary Ceramics. Paper also shows valuable ceramic art forms related with minimalist idea and esthetics. On one hand, ceramics with all the original sensations and emotions of the past, on the other hand Minimal Art as cold, distant and restrained. This study aims to examine the practical interaction of this union unnamed in the history of art. Keywords: Ceramic, Minimalism, Ceramic Art, Contemporary Ceramics, Modern Ceramics Introduction The historical emergence of Minimal Art; Independent, sometimes even disjointed artist practices in minimalist movement and their resistance towards American Abstract Expressionism can be considered as starting point. -

Receiving Newman: Formalism, Minimalism, and Their Philosophical Preconditions Espen Dahl

Receiving Newman: Formalism, minimalism, and their Philosophical Preconditions Espen Dahl abstract Despite the divide between American formalism and theoreti- cians of minimalism, Barnett Newman’s art received great acclaim from both schools of thought. Attempting to unearth the philosophical preconditions of this strange constellation, this article argues that the closeness between minimalism and formalism is due to their mutual reliance upon phenom- enology and ordinary language philosophy. However, their proximity also conveys their distance, since they imply different interpretations and appli- cations of the philosophical schools in question. Such theoretical diffe rences shed light on Newman’s paintings: both minimalism and formalism are right in their accounts – yet not exclusively so. What arguably makes up the dis- tinctive fascination of Newman’s paintings is their incessant oscillation be- tween empty physicality and powerful meaning. keywords Barnett Newman, formalism, minimalism, phenomenology, ordinary language philosophy Barnett Newman’s mature paintings, typically consisting of one or more so-called “zips” on a monochromatic background, are extremely simple, yet powerful. The scarce use of artistic means along with the self-con- tained appearance raise the question as to whether the paintings convey any meaning at all: do Newman’s paintings call upon interpretation and convey some kind of meaning, or have they transgressed the line where the concept of meaning itself is no longer apt – as if the picture morphs into a mere object? Such questions are not new. According to Richard Shiff, critics started dividing into different camps on these central questions already in the 1960s.1 On the one hand, there were those who emphasised the act of creation and the existential subject matter of painting, most famously advocated by Harold Rosenberg. -

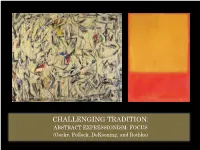

Challenging Tradition

CHALLENGING TRADITION: ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM: FOCUS (Gorky, Pollock, DeKooning, and Rothko) ONLINE ASSIGNMENT: http://smarthistory.khanacademy.org/abstract- expressionism.html TITLE or DESIGNATION: Autumn Rhythm ARTIST: Jackson Pollock CULTURE or ART HISTORICAL PERIOD: Abstract Expressionism DATE: 1950 C.E. MEDIUM: oil, enamel, and aluminum paint on canvas ONLINE ASSIGNMENT: http://www.artic.edu/aic/col lections/artwork/76244 TITLE or DESIGNATION: Excavation ARTIST: Willem De Kooning CULTURE or ART HISTORICAL PERIOD: Abstract Expressionism DATE: 1950 C.E. MEDIUM: oil on canvas ONLINE ASSIGNMENT: http://smarthistory.khana cademy.org/willem-de- kooning.html TITLE or DESIGNATION: Woman I ARTIST: Willem De Kooning CULTURE or ART HISTORICAL PERIOD: Abstract Expressionism DATE: 1950-1951 C.E. MEDIUM: oil on canvas ONLINE ASSIGNMENT: http://www.theguardian.com/ culture/2002/dec/07/artsfeatu res TITLE or DESIGNATION: The Seagram Murals ARTIST: Mark Rothko CULTURE or ART HISTORICAL PERIOD: Abstract Expressionism DATE: Begun 1958 C.E. MEDIUM: oil on canvas TITLE or DESIGNATION: No. 14 ARTIST: Mark Rothko CULTURE or ART HISTORICAL PERIOD: Abstract Expressionism DATE: 1960 C.E. MEDIUM: oil on canvas CHALLENGING TRADITION: ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM: (Gorky, Pollock, DeKooning, and Rothko) ARSHILE GORKY Online Links: Arshile Gorky - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Abstract expressionism - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Surrealist automatism - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Arshile Gorky at the Tate Modern - Financial Times JACKSON POLLOCK and LEE -

Celebrating Suprematism: New Approaches to the Art of Kazimir

Celebrating Suprematism Russian History and Culture Editors-in-Chief Jeffrey P. Brooks (The Johns Hopkins University) Christina Lodder (University of Kent) Volume 22 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/rhc Celebrating Suprematism New Approaches to the Art of Kazimir Malevich Edited by Christina Lodder Cover illustration: Installation photograph of Kazimir Malevich’s display of Suprematist Paintings at The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings, 0.10 (Zero-Ten), in Petrograd, 19 December 1915 – 19 January 1916. Photograph private collection. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Lodder, Christina, 1948- editor. Title: Celebrating Suprematism : new approaches to the art of Kazimir Malevich / edited by Christina Lodder. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, [2019] | Series: Russian history and culture, ISSN1877-7791 ; Volume 22 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN2018037205 (print) | LCCN2018046303 (ebook) | ISBN9789004384989 (E-book) | ISBN 9789004384873 (hardback : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Malevich, Kazimir Severinovich, 1878-1935–Criticism and interpretation. | Suprematism in art. | UNOVIS (Group) Classification: LCCN6999.M34 (ebook) | LCCN6999.M34C452019 (print) | DDC 700.92–dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018037205 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. See and download: brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN1877-7791 ISBN 978-90-04-38487-3 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-38498-9 (e-book) Copyright 2019 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Hes & De Graaf, Brill Nijhoff, Brill Rodopi, Brill Sense, Hotei Publishing, mentis Verlag, Verlag Ferdinand Schöningh and Wilhelm Fink Verlag. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher.