Season 2010 Season 2010-2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WXXI Program Guide | May 2021

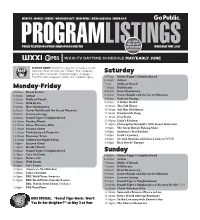

WXXI-TV | WORLD | CREATE | WXXI KIDS 24/7 | WXXI NEWS | WXXI CLASSICAL | WRUR 88.5 SEE CENTER PAGES OF CITY PROGRAMPUBLIC TELEVISION & PUBLIC RADIO FOR ROCHESTER LISTINGSFOR WXXI SHOW MAY/EARLY JUNE 2021 HIGHLIGHTS! WXXI-TV DAYTIME SCHEDULE MAY/EARLY JUNE PLEASE NOTE: WXXI-TV’s daytime schedule listed here runs from 6:00am to 7:00pm. The complete prime time television schedule begins on page 2. Saturday The PBS Kids programs below are shaded in gray. 6:00am Mister Roger’s Neighborhood 6:30am Arthur 7vam Molly of Denali Monday-Friday 7:30am Wild Kratts 6:00am Ready Jet Go! 8:00am Hero Elementary 6:30am Arthur 8:30am Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum 7:00am Molly of Denali 9:00am Curious George 7:30am Wild Kratts 9:30am A Wider World 8:00am Hero Elementary 10:00am This Old House 8:30am Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum 10:30am Ask This Old House 9:00am Curious George 11:00am Woodsmith Shop 9:30am Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood 11:30am Ciao Italia 10:00am Donkey Hodie 12:00pm Lidia’s Kitchen 10:30am Elinor Wonders Why 12:30pm Christopher Kimball’s Milk Street Television 11:00am Sesame Street 1:00pm The Great British Baking Show 11:30am Pinkalicious & Peterrific 2:00pm America’s Test Kitchen 12:00pm Dinosaur Train 2:30pm Cook’s Country 12:30pm Clifford the Big Red Dog 3:00pm Second Opinion with Joan Lunden (WXXI) 1:00pm Sesame Street 3:30pm Rick Steves’ Europe 1:30pm Donkey Hodie 2:00pm Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood Sunday 2:30pm Let’s Go Luna! 6:00am Mister Roger’s Neighborhood 3:00pm Nature Cat 6:30am Arthur 3:30pm Wild Kratts 7:00am Molly -

Doctor Atomic

John Adams Doctor Atomic CONDUCTOR Opera in two acts Alan Gilbert Libretto by Peter Sellars, PRODUCTION adapted from original sources Penny Woolcock Saturday, November 8, 2008, 1:00–4:25pm SET DESIGNER Julian Crouch COSTUME DESIGNER New Production Catherine Zuber LIGHTING DESIGNER Brian MacDevitt CHOREOGRAPHER The production of Doctor Atomic was made Andrew Dawson possible by a generous gift from Agnes Varis VIDEO DESIGN and Karl Leichtman. Leo Warner & Mark Grimmer for Fifty Nine Productions Ltd. SOUND DESIGNER Mark Grey GENERAL MANAGER The commission of Doctor Atomic and the original San Peter Gelb Francisco Opera production were made possible by a generous gift from Roberta Bialek. MUSIC DIRECTOR James Levine Doctor Atomic is a co-production with English National Opera. 2008–09 Season The 8th Metropolitan Opera performance of John Adams’s Doctor Atomic Conductor Alan Gilbert in o r d e r o f v o c a l a p p e a r a n c e Edward Teller Richard Paul Fink J. Robert Oppenheimer Gerald Finley Robert Wilson Thomas Glenn Kitty Oppenheimer Sasha Cooke General Leslie Groves Eric Owens Frank Hubbard Earle Patriarco Captain James Nolan Roger Honeywell Pasqualita Meredith Arwady Saturday, November 8, 2008, 1:00–4:25pm This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. The Met: Live in HD series is made possible by a generous grant from the Neubauer Family Foundation. Additional support for this Live in HD transmission and subsequent broadcast on PBS is provided by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. Ken Howard/Metropolitan Opera Gerald Finley Chorus Master Donald Palumbo (foreground) as Musical Preparation Linda Hall, Howard Watkins, Caren Levine, J. -

A Register of Music Performed in Concert, Nazareth, Pennsylvania from 1796 to 1845: an Annotated Edition of an American Moravian Document

A register of music performed in concert, Nazareth, Pennsylvania from 1796 to 1845: an annotated edition of an American Moravian document Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Strauss, Barbara Jo, 1947- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 23:14:00 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/347995 A REGISTER OF MUSIC PERFORMED IN CONCERT, NAZARETH., PENNSYLVANIA FROM 1796 TO 181+52 AN ANNOTATED EDITION OF AN AMERICAN.MORAVIAN DOCUMENT by Barbara Jo Strauss A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC WITH A MAJOR IN MUSIC HISTORY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1 9 7 6 Copyright 1976 Barbara Jo Strauss STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfill ment of requirements for an advanced degree at The Univer sity of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate ac knowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manu script in whole or in part may -

PROGRAM NOTES Witold Lutosławski Concerto for Orchestra

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Witold Lutosławski Born January 25, 1913, Warsaw, Poland. Died February 7, 1994, Warsaw, Poland. Concerto for Orchestra Lutosławski began this work in 1950 and completed it in 1954. The first performance was given on November 26, 1954, in Warsaw. The score calls for three flutes and two piccolos, three oboes and english horn, three clarinets and bass clarinet, three bassoons and contrabassoon, four horns, four trumpets, four trombones and tuba, timpani, snare drum, side drums, tenor drum, bass drum, cymbals, tam-tam, tambourine, xylophone, bells, celesta, two harps, piano, and strings. Performance time is approximately twenty-eight minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra's first subscription concert performances of Lutosławski's Concerto for Orchestra were given at Orchestra Hall on February 6, 7, and 8, 1964, with Paul Kletzki conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performance was given November 7, 8, and 9, 2002, with Christoph von Dohnányi conducting. The Orchestra has performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival only once, on June 28, 1970, with Seiji Ozawa conducting. For the record The Orchestra recorded Lutosławski's Concerto for Orchestra in 1970 under Seiji Ozawa for Angel, and in 1992 under Daniel Barenboim for Erato. To most musicians today, as to Witold Lutosławski in 1954, the title “concerto for orchestra” suggests Béla Bartók's landmark 1943 score of that name. Bartók's is the most celebrated, but it's neither the first nor the last work with this title. Paul Hindemith, Walter Piston, and Zoltán Kodály all wrote concertos for orchestra before Bartók, and Witold Lutosławski, Michael Tippett, Elliott Carter, and Shulamit Ran are among those who have done so after his famous example. -

Pizzazz on the Podium

Montage Art, books, diverse creations 14 Open Book 15 Bishop Redux 16 Kosher Delights 17 And the War Came 18 Off the Shelf 19 Chapter and Verse 20 Volleys in F# Major places this orchestra square- ly at the center of cultural and intellectual discourse.” The Philharmonic sounds better than it has in decades, too, because Gilbert has im- proved morale, changed the seating plan, and worked on details of tone and balance— even the much-reviled acoustics of Avery Fisher Hall at Lincoln Center sound Alan Gilbert less jagged now. The conducting conductor is also pre- CHRIS LEE the New York Pizzazz on the Podium Philharmonic pared to be surprised: at Avery Fisher to him, his job is both Alan Gilbert’s music that should be heard Hall in Lincoln to lead and take in Center what the musicians by richard dyer are offering. The unexpected hit of his first season ike his celebrated predecessor as diverse as György Ligeti and Wynton was Ligeti’s avant-garde opera, Le Grand Leonard Bernstein ’39, D.Mus. Marsalis, named a composer-in-residence Macabre, in a staging by visual artist Doug ’67, Alan Gilbert ’89 seems to en- (Magnus Lindberg), and started speaking Fitch ’81, a friend who had tutored art in joy whipping up a whirlwind and informally to the audience, as Bernstein Adams House when Gilbert was in col- then taking it for an exhilarating sometimes did. His programs are full of lege. To publicize the opera, Gilbert ap- L ride. Though only in his second year on interconnections and his seasons add peared in three homespun videos that the the job, the second Harvard-educated mu- up; Gilbert has said that every piece tells Philharmonic posted on YouTube; Death, sic director of the New York Philharmonic a story, and every program should, too. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 27,1907-1908, Trip

ACADEMY OF MUSIC, PHILADELPHIA Twenty-third Season in Philadelpnia DR. KARL MUCK, Conductor •Programme of % Fifth and Last Concert WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIP- TIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE MONDAY EVENING, MARCH 16, AT 8.15 PRECISELY PUBLISHED BY C. A. ELLIS, MANAGER : Piano. Used and indorsed by Reisenauer, Neitzel, Burmeister, Gabrilowitsch, Nordica, Campanari, Bispham, and many other noted artists, will be used by TERESA CARRENO during her tour of the United States this season. The Everett piano has been played recently under the baton of the following famous conductors Theodore Thomas Franz Kneisel Dr. Karl Muck Fritz Scheel Walter Damrosch Frank Damrosch Frederick Stock F. Van Der Stucken Wassily Safonoff Emil Oberhoffer Wilhelm Gericke Emil Paur Felix Weingartner REPRESENTED BY THE MUSICAL ECHO CO., 1217 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, Pa. Boston Symphony Orchestra PERSONNEL TWENTY-SEVENTH SEASON, 1907-1908 Dr. KARL MUCK, Conductor First Violins. ~Wendling, Carl, Roth, O. Hoffmann, J. Krafft, W. Concert-master. Kuntz, D. Fiedler, E. Theodorowicz, J. Ozerwonky, R. Mahn, F. Eichheim, H Bak, A. Mullaly, J. Stnibe, G. Rissland, K. Ribarsch, A. Traupe, W. Second Violins. Barleben, K. Akeroyd, J. Fiedler, B. Berger, PI. Fiumara, P. Currier, F. Rennert, B. Eichler, J. Tischer-Zeitz, H Kuntz, A. Swornsbourne, W. Goldstein, S. Kurth, R. Goldstein, H. Violas. Fenr, E. Heindl, H. Zahn, F. Kolster, A. Krauss, H. Scheurer, K. Hoyer, H. Kluge, M. Sauer, G. Gietzen, A. Violoncellos. Warnke, H. Nagel, R. Barth, C. Loeffler, E. Heberlein, H. Keller, J. Kautzenbach, A. Nast, L. Hadley, A. Smalley, R. Basses. Keller, K. Agnesy, K. Seydel, T. Elkind, S. -

11 JANUARY WEDNESDAY SERIES 9 Helsinki Music Centre at 7 Pm

11 JANUARY WEDNESDAY SERIES 9 Helsinki Music Centre at 7 pm Sakari Oramo, conductor Jukka Harju, horn József Hárs, horn Markus Maskuniitty, horn Esa Tapani, horn Magnus Lindberg: Al largo 25 min Robert Schumann: Konzertstück in F Major for Four Horns and Orchestra, Op. 86 21 min I Lebhaft II Romance (Ziemlich langsam, doch nicht schleppend) III Sehr lebhaft INTERVAL 20 MIN Felix Mendelssohn: Symphony No. 4 in A Major, Op. 90, “The Italian” 30 min I Allegro vivace II Andante con moto III Con moto moderato IV Saltarello (Presto) Interval at about 7.55 pm. The concert ends at about 9 pm. Broadcast live on YLE Radio 1 and the Internet (yle.fi/rso). 1 MAGNUS LINDBERG up and present us with the next, equal- ly dazzling landscape. Structurally, Al lar- (1958–): AL LARGO go falls into two broad sections, “that both begin very vigorously and end as slow mu- The avoidance of anything slow was for a sic”. Dominating the first half are numerous long time a fundamental feature of the mu- brass fanfares that vary in their details, sup- sic of Magnus Lindberg. Even if the tempo ported by a seething brew in the rest of the marking was somewhat on the slow side, orchestra. After a big climax the music sud- the texture would seethe and bubble like denly becomes introspective, borne alone a piping-hot broth and, what is more, with by a delightful string texture. The return of an energy little short of manic. In this res- the fanfares leads to a new build-up and ul- pect it is exciting to hear what awaits in the timately to a mighty oboe solo on which the orchestral work he wrote last year, for as music muses for a good while. -

2020-21 Season Brochure

2020 SEA- This year. This season. This orchestra. This music director. Our This performance. This artist. World This moment. This breath. This breath. 2021 SON This breath. Don’t blink. ThePhiladelphiaOrchestra MUSIC DIRECTOR YANNICK NÉZET-SÉGUIN our world Ours is a world divided. And yet, night after night, live music brings audiences together, gifting them with a shared experience. This season, Music Director Yannick Nézet-Séguin and The Philadelphia Orchestra invite you to experience the transformative power of fellowship through a bold exploration of sound. 2 2020–21 Season 3 “For me, music is more than an art form. It’s an artistic force connecting us to each other and to the world around us. I love that our concerts create a space for people to gather as a community—to explore and experience an incredible spectrum of music. Sometimes, we spend an evening in the concert hall together, and it’s simply some hours of joy and beauty. Other times there may be an additional purpose, music in dialogue with an issue or an idea, maybe historic or current, or even a thought that is still not fully formed in our minds and hearts. What’s wonderful is that music gives voice to ideas and feelings that words alone do not; it touches all aspects of our being. Music inspires us to reflect deeply, and music brings us great joy, and so much more. In the end, music connects us more deeply to Our World NOW.” —Yannick Nézet-Séguin 4 2020–21 Season 5 philorch.org / 215.893.1955 6A Thursday Yannick Leads Return to Brahms and Ravel Favorites the Academy Garrick Ohlsson Thursday, October 1 / 7:30 PM Thursday, January 21 / 7:30 PM Thursday, March 25 / 7:30 PM Academy of Music, Philadelphia Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Michael Tilson Thomas Conductor Lisa Batiashvili Violin Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Garrick Ohlsson Piano Hai-Ye Ni Cello Westminster Symphonic Choir Ravel Le Tombeau de Couperin Joe Miller Director Szymanowski Violin Concerto No. -

RCM Clarinet Syllabus / 2014 Edition

FHMPRT396_Clarinet_Syllabi_RCM Strings Syllabi 14-05-22 2:23 PM Page 3 Cla rinet SYLLABUS EDITION Message from the President The Royal Conservatory of Music was founded in 1886 with the idea that a single institution could bind the people of a nation together with the common thread of shared musical experience. More than a century later, we continue to build and expand on this vision. Today, The Royal Conservatory is recognized in communities across North America for outstanding service to students, teachers, and parents, as well as strict adherence to high academic standards through a variety of activities—teaching, examining, publishing, research, and community outreach. Our students and teachers benefit from a curriculum based on more than 125 years of commitment to the highest pedagogical objectives. The strength of the curriculum is reinforced by the distinguished College of Examiners—a group of fine musicians and teachers who have been carefully selected from across Canada, the United States, and abroad for their demonstrated skill and professionalism. A rigorous examiner apprenticeship program, combined with regular evaluation procedures, ensures consistency and an examination experience of the highest quality for candidates. As you pursue your studies or teach others, you become not only an important partner with The Royal Conservatory in the development of creativity, discipline, and goal- setting, but also an active participant, experiencing the transcendent qualities of music itself. In a society where our day-to-day lives can become rote and routine, the human need to find self-fulfillment and to engage in creative activity has never been more necessary. The Royal Conservatory will continue to be an active partner and supporter in your musical journey of self-expression and self-discovery. -

Solo and Ensemble Concert Mae Zenke Orvis Auditorium July 17, 1967 8:00 P.M

SOLO AND ENSEMBLE CONCERT MAE ZENKE ORVIS AUDITORIUM JULY 17, 1967 8:00 P.M. SOLO AND ENSEMBLE CONCERT Monday, July 17 Mae Zenke Orvis Auditorium 8:00 P.M. Program Ernst Krenek Piano Sonata No.3 (1943) Peter Coraggio, piano Allegretto piacevole Theme, Canons and Variations: Andantino Scherzo: Vivace rna non troppo Adagio First Performance in Hawaii Neil McKay Sonata for French Horn and Willard Culley, French horn Piano (1962) Marion McKay, piano Fanfare: Allegro Andante Allegro First Performance in Hawaii Chou Wen-chung Yu Ko (1965) Chou Wen-chung, conductor First Performance in Hawaii John Merrill, violin Jean Harling, alto flute James Ostryniec, English horn Henry Miyamura, bass clarinet Roy Miyahira, trombone Samuel Aranio, bass trombone Zoe Merrill, piano Lois Russell, percussion Edward Asmus, percussion INTERMISSION JOSe Maceda Kubing (1966) Jose Maceda, conductor Music for Bamboo Percussion and Men's Voices First Performance in Hawaii Jose Maceda Kubing (1966) Jose Maceda, conductor Music for Bamboo Percussion Charles Higgins and Men's Voices William Feltz First Performance in Hawaii Brian Roberts voices San Do Alfredo lagaso John Van der Slice l Takefusa Sasamori tubes Bach Mai Huong Ta buzzers ~ Ruth Pfeiffer jaw's harps Earlene Tom Thi Hanh le William Steinohrt Marcia Chang zithers Michael Houser } Auguste Broadmeyer Nancy Waller scrapers Hailuen } Program Notes The Piano Sonata NO.3 was written in 1943. The first movement is patterned after the classical model: expo sition (with first, second, and concluding themes), development, recapitulation, and coda. However, in each of these sections the thematic material is represented in musical configurations derived from one of the four basic forms of the twelve-tone row: original, inversion, retrograde, and retrograde inversion. -

Season 2016-2017

23 Season 2016-2017 Thursday, January 26, at 8:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra Friday, January 27, at 2:00 City of Light and Music: The Paris Festival, Week 3 Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Choong-Jin Chang Viola Berlioz Harold in Italy, Op. 16 I. Harold in the Mountains (Scenes of melancholy, happiness, and joy) II. Pilgrims’ March—Singing of the Evening Hymn III. Serenade of an Abruzzi Mountaineer to his Sweetheart IV. Brigands’ Orgy (Reminiscences of the preceding scenes) Intermission Ravel Alborada del gracioso Ravel Rapsodie espagnole I. Prelude to the Night— II. Malagueña III. Habanera IV. Feria Ravel Bolero This program runs approximately 1 hour, 55 minutes. The January 26 concert is sponsored in memory of Ruth W. Williams. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM. Visit WRTI.org to listen live or for more details. 24 Steven Spielberg’s filmE.T. the Extra-Terrestrial has always held a special place in my heart, and I personally think it’s his masterpiece. In looking at it today, it’s as fresh and new as when it was made in 1982. Cars may change, along with hairstyles and clothes … but the performances, particularly by the children and by E.T. himself, are so honest, timeless, and true, that the film absolutely qualifies to be ranked as a classic. What’s particularly special about today’s concert is that we’ll hear one of our great symphony orchestras, The Philadelphia Orchestra, performing the entire score live, along with the complete picture, sound effects, and dialogue. -

Magnus Lindberg 1

21ST CENTURY MUSIC FEBRUARY 2010 INFORMATION FOR SUBSCRIBERS 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC is published monthly by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC, P.O. Box 2842, San Anselmo, CA 94960. ISSN 1534-3219. Subscription rates in the U.S. are $96.00 per year; subscribers elsewhere should add $48.00 for postage. Single copies of the current volume and back issues are $12.00. Large back orders must be ordered by volume and be pre-paid. Please allow one month for receipt of first issue. Domestic claims for non-receipt of issues should be made within 90 days of the month of publication, overseas claims within 180 days. Thereafter, the regular back issue rate will be charged for replacement. Overseas delivery is not guaranteed. Send orders to 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC, P.O. Box 2842, San Anselmo, CA 94960. email: [email protected]. Typeset in Times New Roman. Copyright 2010 by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC. This journal is printed on recycled paper. Copyright notice: Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC. INFORMATION FOR CONTRIBUTORS 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC invites pertinent contributions in analysis, composition, criticism, interdisciplinary studies, musicology, and performance practice; and welcomes reviews of books, concerts, music, recordings, and videos. The journal also seeks items of interest for its calendar, chronicle, comment, communications, opportunities, publications, recordings, and videos sections. Copy should be double-spaced on 8 1/2 x 11 -inch paper, with ample margins. Authors are encouraged to submit via e-mail. Prospective contributors should consult The Chicago Manual of Style, 15th ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), in addition to back issues of this journal.