Lizards & Snakes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dietary Behavior of the Mangrove Monitor Lizard (Varanus Indicus)

DIETARY BEHAVIOR OF THE MANGROVE MONITOR LIZARD (VARANUS INDICUS) ON COCOS ISLAND, GUAM, AND STRATEGIES FOR VARANUS INDICUS ERADICATION A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI’I AT HILO IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN TROPICAL CONSERVATION BIOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE MAY 2016 By Seamus P. Ehrhard Thesis Committee: William Mautz, Chairperson Donald Price Patrick Hart Acknowledgements I would like to thank Guam’s Department of Agriculture, the Division of Aquatic and Wildlife Resources, and wildlife biologist, Diane Vice, for financial assistance, research materials, and for offering me additional staffing, which greatly aided my fieldwork on Guam. Additionally, I would like to thank Dr. William Mautz for his consistent help and effort, which exceeded all expectations of an advisor, and without which I surely would have not completed my research or been inspired to follow my passion of herpetology to the near ends of the earth. 2 Abstract The mangrove monitor lizard (Varanus indicus), a large invasive predator, can be found on all areas of the 38.6 ha Cocos Island at an estimated density, in October 2011, of 6 V. Indicus per hectare on the island. Plans for the release of the endangered Guam rail (Gallirallus owstoni) on Cocos Island required the culling of V. Indicus, because the lizards are known to consume birds and bird eggs. Cocos Island has 7 different habitats; resort/horticulture, Casuarina forest, mixed strand forest, Pemphis scrub, Scaevola scrub, sand/open area, and wetlands. I removed as many V. Indicus as possible from the three principal habitats; Casuarina forest, mixed scrub forest, and a garbage dump (resort/horticulture) using six different trapping methods. -

Veiled Chameleon Care Sheet Because We Care !!!

Veiled Chameleon Care Sheet Because we care !!! 1250 Upper Front Street, Binghamton, NY 13901 607-723-2666 Congratulations on your new pet. The popularity of the veiled chameleon is due to a number of factors: veiled chameleons are relatively hardy, large, beautiful, and prolific. Veiled chameleons are native to Yemen and southern Saudi Arabia, they are quite tolerant of tem- perature and humidity extremes, which contributes to its hardiness as a captive. Veiled chameleons are among the easiest chameleons to care for, but they still require careful attention. They range in size from 6-12 inches and will live up to five years with the proper care. Males tend to be larger and more colorful than females. With their ability to change colors, prehensile tails, independently moving eyes and stuttering walk make them fascinating to watch. They become stressed very easily so regular handling is not recommended. HOUSING A full-screen enclosure is a must for veiled chameleons. Zoomed’s ReptiBreeze is an ideal habitat. Glass aquariums can lead to respiratory diseases due to the stagnant air not being circulated, and they will be stressed if they can see their reflection. These Chameleons also need a large enclosure to climb around in because smaller enclosures will stress them. A 3’x3’x3’ or 2’x2’x4’ habitat is best, but larger is bet- ter. Chameleons should be house separately to avoid fighting. The interior of the enclosure should be furnished with medium sized vines and foliage for the chameleons to hide in. The medium sized vines provide important horizontal perches for the chameleon to rest and bask. -

West Indian Iguana Husbandry Manual

1 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 4 Natural history ............................................................................................................................... 7 Captive management ................................................................................................................... 25 Population management .............................................................................................................. 25 Quarantine ............................................................................................................................... 26 Housing..................................................................................................................................... 26 Proper animal capture, restraint, and handling ...................................................................... 32 Reproduction and nesting ........................................................................................................ 34 Hatchling care .......................................................................................................................... 40 Record keeping ........................................................................................................................ 42 Husbandry protocol for the Lesser Antillean iguana (Iguana delicatissima)................................. 43 Nutrition ...................................................................................................................................... -

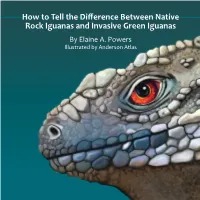

How to Tell the Difference Between Native Rock Iguanas and Invasive Green Iguanas by Elaine A

How to Tell the Difference Between Native Rock Iguanas and Invasive Green Iguanas By Elaine A. Powers Illustrated by Anderson Atlas Many of the islands in the Caribbean Sea, known as the West Rock Iguanas (Cyclura) Indies, have native iguanas. B Cuban Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila), Cuba They are called Rock Iguanas. C Sister Isles Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila caymanensis), Cayman Brac and Invasive Green Iguanas have been introduced on these islands and Little Cayman are a threat to the Rock Iguanas. They compete for food, territory D Grand Cayman Blue Iguana (Cyclura lewisi), Grand Cayman and nesting areas. E Jamaican Rock Iguana (Cyclura collei), Jamaica This booklet is designed to help you identify the native Rock F Turks & Caicos Rock Iguana (Cyclura carinata), Turks and Caicos. Iguanas from the invasive Greens. G Booby Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura carinata bartschi), Booby Cay, Bahamas H Andros Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura), Andros, Bahamas West Indies I Exuma Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura figginsi), Exuma Islands, Bahamas Exumas BAHAMAS J Allen’s Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura inornata), Exuma Islands, J Islands Bahamas M San Salvador Andros Island H Booby Cay K Anegada Iguana (Cyclura pinguis), British Virgin Islands Allens Cay White G I Cay Ricord’s Iguana (Cyclura ricordi), Hispaniola O F Turks & Caicos L CUBA NAcklins Island M San Salvador Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi), San Salvador, Bahamas Anegada HISPANIOLA CAYMAN ISLANDS K N Acklins Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi nuchalis), Acklins Islands, Bahamas B PUERTO RICO O White Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi cristata), Exuma Islands, Bahamas Grand Cayman D C JAMAICA BRITISH P Rhinoceros Iguana (Cyclura cornuta), Hispanola Cayman Brac & VIRGIN Little Cayman E L P Q Mona ISLANDS Q Mona Island Iguana (Cyclura stegnegeri), Mona Island, Puerto Rico Island 2 3 When you see an iguana, ask: What kind do I see? Do you see a big face scale, as round as can be? What species is that iguana in front of me? It’s below the ear, that’s where it will be. -

Addo Elephant National Park Reptiles Species List

Addo Elephant National Park Reptiles Species List Common Name Scientific Name Status Snakes Cape cobra Naja nivea Puffadder Bitis arietans Albany adder Bitis albanica very rare Night adder Causes rhombeatus Bergadder Bitis atropos Horned adder Bitis cornuta Boomslang Dispholidus typus Rinkhals Hemachatus hemachatus Herald/Red-lipped snake Crotaphopeltis hotamboeia Olive house snake Lamprophis inornatus Night snake Lamprophis aurora Brown house snake Lamprophis fuliginosus fuliginosus Speckled house snake Homoroselaps lacteus Wolf snake Lycophidion capense Spotted harlequin snake Philothamnus semivariegatus Speckled bush snake Bitis atropos Green water snake Philothamnus hoplogaster Natal green watersnake Philothamnus natalensis occidentalis Shovel-nosed snake Prosymna sundevalli Mole snake Pseudapsis cana Slugeater Duberria lutrix lutrix Common eggeater Dasypeltis scabra scabra Dappled sandsnake Psammophis notosticus Crossmarked sandsnake Psammophis crucifer Black-bellied watersnake Lycodonomorphus laevissimus Common/Red-bellied watersnake Lycodonomorphus rufulus Tortoises/terrapins Angulate tortoise Chersina angulata Leopard tortoise Geochelone pardalis Green parrot-beaked tortoise Homopus areolatus Marsh/Helmeted terrapin Pelomedusa subrufa Tent tortoise Psammobates tentorius Lizards/geckoes/skinks Rock Monitor Lizard/Leguaan Varanus niloticus niloticus Water Monitor Lizard/Leguaan Varanus exanthematicus albigularis Tasman's Girdled Lizard Cordylus tasmani Cape Girdled Lizard Cordylus cordylus Southern Rock Agama Agama atra Burrowing -

Suggested Guidelines for Reptiles and Amphibians Used in Outreach

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR REPTILES AND AMPHIBIANS USED IN OUTREACH PROGRAMS Compiled by Diane Barber, Fort Worth Zoo Originally posted September 2003; updated February 2008 INTRODUCTION This document has been created by the AZA Reptile and Amphibian Taxon Advisory Groups to be used as a resource to aid in the development of institutional outreach programs. Within this document are lists of species that are commonly used in reptile and amphibian outreach programs. With over 12,700 species of reptiles and amphibians in existence today, it is obvious that there are numerous combinations of species that could be safely used in outreach programs. It is not the intent of these Taxon Advisory Groups to produce an all-inclusive or restrictive list of species to be used in outreach. Rather, these lists are intended for use as a resource and are some of the more common species that have been safely used in outreach programs. A few species listed as potential outreach animals have been earmarked as controversial by TAG members for various reasons. In each case, we have made an effort to explain debatable issues, enabling staff members to make informed decisions as to whether or not each animal is appropriate for their situation and the messages they wish to convey. It is hoped that during the species selection process for outreach programs, educators, collection managers, and other zoo staff work together, using TAG Outreach Guidelines, TAG Regional Collection Plans, and Institutional Collection Plans as tools. It is well understood that space in zoos is limited and it is important that outreach animals are included in institutional collection plans and incorporated into conservation programs when feasible. -

Human Mast Cell Tryptase Is a Potential Treatment for Snakebite

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 09 July 2018 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01532 Human Mast Cell Tryptase Is a Potential Treatment for Snakebite Edited by: Envenoming Across Multiple Snake Ulrich Blank, Institut National de la Santé Species et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM), France Elizabeth Anderson1†, Kathrin Stavenhagen 2†, Daniel Kolarich 2†, Christian P. Sommerhoff 3, Reviewed by: Marcus Maurer 1 and Martin Metz 1* Nicolas Gaudenzio, Institut National de la Santé 1 Department of Dermatology and Allergy, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany, 2 Department of Biomolecular et de la Recherche Médicale Systems, Max Planck Institute of Colloids and Interfaces, Potsdam, Germany, 3 Institute of Laboratory Medicine, University (INSERM), France Hospital, Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Munich, Germany Axel Lorentz, University of Hohenheim, Germany Snake envenoming is a serious and neglected public health crisis that is responsible *Correspondence: for as many as 125,000 deaths per year, which is one of the reasons the World Health Martin Metz Organization has recently reinstated snakebite envenoming to its list of category A [email protected] neglected tropical diseases. Here, we investigated the ability of human mast cell prote- †Present address: Elizabeth Anderson, ases to detoxify six venoms from a spectrum of phylogenetically distinct snakes. To this School of Medicine, UC end, we developed a zebrafish model to assess effects on the toxicity of the venoms San Diego, San Diego, CA, United States; and characterized the degradation of venom proteins by mass spectrometry. All snake Kathrin Stavenhagen, venoms tested were detoxified by degradation of various venom proteins by the mast Department of Surgery, cell protease tryptase , and not by other proteases. -

Changes to CITES Species Listings

NOTICE TO THE WILDLIFE IMPORT/EXPORT COMMUNITY December 21, 2016 Subject: Changes to CITES Species Listings Background: Party countries of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) meet approximately every two years for a Conference of the Parties. During these meetings, countries review and vote on amendments to the listings of protected species in CITES Appendix I and Appendix II. Such amendments become effective 90 days after the last day of the meeting unless Party countries agree to delay implementation. The most recent Conference of the Parties (CoP 17) was held in Johannesburg, South Africa, September 24 – October 4, 2016. Action: Except as noted below, the amendments to CITES Appendices I and II that were adopted at CoP 17, will be effective on January 2, 2017. Any specimens of these species imported into, or exported from, the United States on or after January 2, 2017 will require CITES documentation as specified under the amended listings. The import, export, or re-export of shipments of these species that are accompanied by CITES documents reflecting a pre-January 2 listing status or that lack CITES documents because no listing was previously in effect must be completed by midnight (local time at the point of import/export) on January 1, 2017. Importers and exporters can find the official revised CITES appendices on the CITES website. Species Added to Appendix I . Abronia anzuetoi (Alligator lizard) . Abronia campbelli (Alligator lizard) . Abronia fimbriata (Alligator lizard) . Abronia frosti (Alligator lizard) . Abronia meledona (Alligator lizard) . Cnemaspis psychedelica (Psychedelic rock gecko) . Lygodactylus williamsi (Turquoise dwarf gecko) . Telmatobius coleus (Titicaca water frog) . -

Reptiles of the Wet Tropics

Reptiles of the Wet Tropics The concentration of endemic reptiles in the Wet Tropics is greater than in any other area of Australia. About 162 species of reptiles live in this region and 24 of these species live exclusively in the rainforest. Eighteen of them are found nowhere else in the world. Many lizards are closely related to species in New Guinea and South-East Asia. The ancestors of two of the resident geckos are thought to date back millions of years to the ancient super continent of Gondwana. PRICKLY FOREST SKINK - Gnypetoscincus queenlandiae Length to 17cm. This skink is distinguished by its very prickly back scales. It is very hard to see, as it is nocturnal and hides under rotting logs and is extremely heat sensitive. Located in the rainforest in the Wet Tropics only, from near Cooktown to west of Cardwell. RAINFOREST SKINK - Eulamprus tigrinus Length to 16cm. The body has irregular, broken black bars. They give birth to live young and feed on invertebrates. Predominantly arboreal, they bask in patches of sunlight in the rainforest and shelter in tree hollows at night. Apparently capable of producing a sharp squeak when handled or when fighting. It is rare and found only in rainforests from south of Cooktown to west of Cardwell. NORTHERN RED-THROATED SKINK - Carlia rubrigularis Length to 14cm. The sides of the neck are richly flushed with red in breeding males. Lays 1-2 eggs per clutch, sometimes communally. Forages for insects in leaf litter, fallen logs and tree buttresses. May also prey on small skinks and own species. -

Printable PDF Format

Field Guides Tour Report Australia Part 2 2019 Oct 22, 2019 to Nov 11, 2019 John Coons & Doug Gochfeld For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. Water is a precious resource in the Australian deserts, so watering holes like this one near Georgetown are incredible places for concentrating wildlife. Two of our most bird diverse excursions were on our mornings in this region. Photo by guide Doug Gochfeld. Australia. A voyage to the land of Oz is guaranteed to be filled with novelty and wonder, regardless of whether we’ve been to the country previously. This was true for our group this year, with everyone coming away awed and excited by any number of a litany of great experiences, whether they had already been in the country for three weeks or were beginning their Aussie journey in Darwin. Given the far-flung locales we visit, this itinerary often provides the full spectrum of weather, and this year that was true to the extreme. The drought which had gripped much of Australia for months on end was still in full effect upon our arrival at Darwin in the steamy Top End, and Georgetown was equally hot, though about as dry as Darwin was humid. The warmth persisted along the Queensland coast in Cairns, while weather on the Atherton Tablelands and at Lamington National Park was mild and quite pleasant, a prelude to the pendulum swinging the other way. During our final hours below O’Reilly’s, a system came through bringing with it strong winds (and a brush fire warning that unfortunately turned out all too prescient). -

1 the Multiscale Hierarchical Structure of Heloderma Suspectum

The multiscale hierarchical structure of Heloderma suspectum osteoderms and their mechanical properties. Francesco Iacoviello a, Alexander C. Kirby b, Yousef Javanmardi c, Emad Moeendarbary c, d, Murad Shabanli c, Elena Tsolaki b, Alana C. Sharp e, Matthew J. Hayes f, Kerda Keevend g, Jian-Hao Li g, Daniel J.L. Brett a, Paul R. Shearing a, Alessandro Olivo b, Inge K. Herrmann g, Susan E. Evans e, Mehran Moazen c, Sergio Bertazzo b,* a Electrochemical Innovation Lab, Department of Chemical Engineering University College London, London WC1E 7JE, UK. b Department of Medical Physics & Biomedical Engineering University College London, London WC1E 6BT, UK. c Department of Mechanical Engineering University College London, London WC1E 7JE, UK. d Department of Biological Engineering Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, 02139, USA. e Department of Cell & Developmental Biology University College London, London WC1E 6BT, UK. f Department of Ophthalmology University College London, London WC1E 6BT, UK. g Department of Materials Meet Life Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology (Empa) Lerchenfeldstrasse 5, CH-9014, St. Gallen, Switzerland. * Correspondence: Sergio Bertazzo [email protected] Tel: +44 (0) 2076790444 1 Abstract Osteoderms are hard tissues embedded in the dermis of vertebrates and have been suggested to be formed from several different mineralized regions. However, their nano architecture and micro mechanical properties had not been fully characterized. Here, using electron microscopy, µ-CT, atomic force microscopy and finite element simulation, an in-depth characterization of osteoderms from the lizard Heloderma suspectum, is presented. Results show that osteoderms are made of three different mineralized regions: a dense apex, a fibre-enforced region comprising the majority of the osteoderm, and a bone-like region surrounding the vasculature. -

AC31 Doc. 14.2

Original language: English AC31 Doc. 14.2 CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ___________________ Thirty-first meeting of the Animals Committee Geneva (Switzerland), 13-17 July 2020 Interpretation and implementation matters Regulation of trade Non-detriment findings PUBLICATION OF A MANAGEMENT REPORT FOR COMMON WATER MONITORS (VARANUS SALVATOR) IN PENINSULAR MALAYSIA 1. This document has been submitted by Malaysia (Management Authorities of Peninsular Malaysia – Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources and Department of Wildlife and National Park Peninsular Malaysia).* Background 2. For the last 50 years, Malaysia has sustained a trade in the skins of Common Water Monitors (Varanus salvator), listed in Appendix II since 1975. In accordance of Article IV, paragraph 3, exports of the specimens of Appendix-II species must be monitored continuously and suitable measures to be taken to limit such exports in order to maintain such species throughout their range at a level consistent with their role in the ecosystems and well above the level at which they would qualify for Appendix I. 3. The CITES Scientific and Management Authorities of Peninsular Malaysia committed to improve monitoring and management systems for Varanus salvator in Malaysia, which has resulted in the management system published here (Annex). Objectives and overview of the Management System for Varanus salvator 4. The management report provides information on the biological attributes of V. salvator, recent population data findings in Peninsular Malaysia and the monitoring and management systems used to ensure its sustainable trade. 5. The main specific objectives of the management report are: a) To provide a tool to support wildlife management authorities in Malaysia in the application of CITES provisions such as Non-detriment findings (NDFs).