A Brief History of Appomattox County

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How the Civil War Became the Indian Wars

Price of Freedom: Stories of Sacrifice How the Civil War Became the Indian Wars New York Times Article By Boyd Cothran and Ari Kelman May 25, 2015 On Dec. 21, 1866, a year and a half after Gen. Robert E. Lee and Gen. Ulysses S. Grant ostensibly closed the book on the Civil War’s final chapter at Appomattox Court House, another soldier, Capt. William Fetterman, led cavalrymen from Fort Phil Kearny, a federal outpost in Wyoming, toward the base of the Big Horn range. The men planned to attack Indians who had reportedly been menacing local settlers. Instead, a group of Arapahos, Cheyennes and Lakotas, including a warrior named Crazy Horse, killed Fetterman and 80 of his men. It was the Army’s worst defeat on the Plains to date. The Civil War was over, but the Indian wars were just beginning. These two conflicts, long segregated in history and memory, were in fact intertwined. They both grew out of the process of establishing an American empire in the West. In 1860, competing visions of expansion transformed the presidential election into a referendum. Members of the Republican Party hearkened back to Jefferson’s dream of an “empire for liberty.” The United States, they said, should move west, leaving slavery behind. This free soil platform stood opposite the splintered Democrats’ insistence that slavery, unfettered by federal regulations, should be allowed to root itself in new soil. After Abraham Lincoln’s narrow victory, Southern states seceded, taking their congressional delegations with them. Never ones to let a serious crisis go to waste, leading Republicans seized the ensuing constitutional crisis as an opportunity to remake the nation’s political economy and geography. -

1 Buell, Augustus. “The Cannoneer.” Recollections of Service in the Army

Buell, Augustus. “The Cannoneer.” Recollections of Service in the Army of the Potomac. Washington: National Tribune, 1890. 4th United States Artillery Regular artillery, history, Battery B, 11-16 Weapons, officers, organization, cannon, 17-23 Officers, 23-27 Camp layout, 27-28 Second Bull Run, 29-31 Antietam campaign, casualties, 31-43 McClellan, 41-42 Fredericksburg, artillery in the battle, casualties, 44-47 Characters in the battery, 48 Hooker, soldiers and generals, 49 Artillery organization, 51 Chancellorsville, 51-53 Amateur opera, 53-54 Artillery organization, 56-59 Demoralization, criticism of McClellan and Hooker, 60-61 March to Gettysburg, 61-64 Gettysburg, railroad cut, 64-100 Review of Gettysburg, numbers and losses, 101-118 Defends Meade on pursuit of Lee, 118, 122-23 Gettysburg after the battle, 120-21 Badly wounded horse, 121 Going over an old battlefield, Groveton, 124 Alcohol, 126 Young men in the battery, 126-28, 132 Foraging, fight, 128 Sutler wagon tips over, 128 Losses in the battery, 129 Raids on sutlers and rambunctious behavior, 131 Bristoe Station, 133 Scout, information about Confederate supplies, 134-35 Changes in artillery organization, 135-36 Winter quarters, On to Richmond editors, 137 Deserters, executions, 138-141 Hazing, 142 Army of the Potomac, veterans, 143 Fifth Corps, artillery, 143-52 West Point men, 148 Better discipline, Grant, 152-55 Crossing the Rapidan, veterans, spring campaign, 155-57 Overland campaign, 158ff Wilderness, 158-75 Spotsylvania Courthouse, 177-199 1 Sedgwick death, 184 Discipline, -

Two New Mexican Lives Through the Nineteenth Century

Hannigan 1 “Overrun All This Country…” Two New Mexican Lives Through the Nineteenth Century “José Francisco Chavez.” Library of Congress website, “General Nicolás Pino.” Photograph published in Ralph Emerson Twitchell, The History of the Military July 15 2010, https://www.loc.gov/rr/hispanic/congress/chaves.html Occupation of the Territory of New Mexico, 1909. accessed March 16, 2018. Isabel Hannigan Candidate for Honors in History at Oberlin College Advisor: Professor Tamika Nunley April 20, 2018 Hannigan 2 Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................... 2 I. “A populace of soldiers”, 1819 - 1848. ............................................................................................... 10 II. “May the old laws remain in force”, 1848-1860. ............................................................................... 22 III. “[New Mexico] desires to be left alone,” 1860-1862. ...................................................................... 31 IV. “Fighting with the ancient enemy,” 1862-1865. ............................................................................... 53 V. “The utmost efforts…[to] stamp me as anti-American,” 1865 - 1904. ............................................. 59 Conclusion .............................................................................................................................................. 72 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................ -

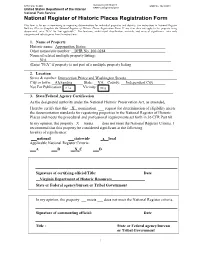

Appomattox Statue Other Names/Site Number: DHR No

NPS Form 10-900 VLR Listing 03/16/2017 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior NRHP Listing 06/12/2017 National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: Appomattox Statue Other names/site number: DHR No. 100-0284 Name of related multiple property listing: N/A (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: Intersection Prince and Washington Streets City or town: Alexandria State: VA County: Independent City Not For Publication: N/A Vicinity: N/A ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements -

The Last Wilderness Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE LAST WILDERNESS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Erin Hunter | 265 pages | 31 May 2012 | HarperCollins Publishers Inc | 9780060871338 | English | New York, NY, United States The Last Wilderness PDF Book He is a knowledgeable and generous guide to the unique flora and fauna of this beautiful corner of Scotland' - James Macdonald Lockhart, author of Raptor'. Top Stories. Though guide and porter services are often associated with epic international destinations, many domestic outfitters also offer these options. By using ThoughtCo, you accept our. Through his keen eyes we look again at the familiar with a sense of wondrous revelation' - Madeleine Bunting. Men on both sides stumbled into enemy camps and were made prisoners, and fires ignited by rifle bursts and exploding shells trapped and killed many of the wounded. My Life in Red and White. He has two daughters and lives in Brighton. Meade's Army of the Potomac. Muriel McComber is a year-old girl and the love of Richard's life. Burnside's corps was ordered to enter the gap between the turnpike and plank road to threaten the enemy rear. Ask Approved: 21 of the Best Reads of As Union troops rested, they were forced to spend the night in the Wilderness of Spotsylvania, a vast area of thick, second-growth forest that negated the Union advantage in manpower and artillery. Your local Waterstones may have stock of this item. The script identifies her as being around 50 years old. You can watch a rehearsal of this scene here. Neil Ansell Neil Ansell was an award-winning television journalist with the BBC and a long standing newspaper journalist. -

Battle-Of-Waynesboro

Battlefield Waynesboro Driving Tour AREA AT WAR The Battle of Waynesboro Campaign Timeline 1864-1865: Jubal Early’s Last Stand Sheridan’s Road The dramatic Union victory at the Battle of Cedar Creek on October 19, 1864, had effectively ended to Petersburg Confederate control in the Valley. Confederate Gen. Jubal A. Early “occasionally came up to the front and Winchester barked, but there was no more bite in him,” as one Yankee put it. Early attempted a last offensive in mid- October 19, 1864 November 1864, but his weakened cavalry was defeated by Union Gen. Philip H. Sheridan’s cavalry at Kernstown Union Gen. Philip H. Sheridan Newtown (Stephens City) and Ninevah, forcing Early to withdraw. The Union cavalry now so defeats Confederate Gen. Jubal A. Early at Cedar Creek. overpowered his own that Early could no longer maneuver offensively. A Union reconnaissance Strasburg Front Royal was repulsed at Rude’s Hill on November 22, and a second Union cavalry raid was turned mid-November 1864 back at Lacey Spring on December 21, ending active operations for the winter season. Early’s weakened cavalry The winter was disastrous for the Confederate army, which was no longer able is defeated in skirmishes at to sustain itself on the produce of the Valley, which had been devastated by Newtown and Ninevah. the destruction of “The Burning.” Rebel cavalry and infantry were returned November 22, to Lee’s army at Petersburg or dispersed to feed and forage for themselves. 1864 Union cavalry repulsed in a small action at Rude’s Hill. Prelude to Battle Harrisonburg December 21, McDowell 1864 As the winter waned and spring approached, Confederates defeat Federals the Federals began to move. -

Buford-Duke Family Album Collection, Circa 1860S (001PC)

Buford-Duke Family Album Collection, circa 1860s (001PC) Photograph album, ca. 1860s, primarily made up of CDVs but includes four tintypes, in which almost all of the images are identified. Many of the persons identified are members of the Buford and Duke families but members of the Taylor and McDowell families are also present. There are also photographs of many Civil War generals and soldiers. Noted individuals include George Stoneman, William Price Sanders, Phillip St. George Cooke, Ambrose Burnside, Ethan Allen Hitchcock, George Gordon Meade, Napoleon Bonaparte Buford, George Brinton McClellan, Wesley Merritt, John Buford, Winfred Scott Hancock, John C. Fremont, Green Clay Smith, Basil Wilson Duke, Philip Swigert, John J. Crittenden and Davis Tillson. The photographs are in good condition but the album cover is coming apart and is in very poor condition and the album pages range from fair to good condition. A complete list of the identified persons is as follows: Buford-Duke, 1 Buford-Duke Family Album Collection, circa 1860s (001PC) Page 1: Page 4 (back page): Top Left - George Stoneman Captain Joseph O'Keefe (?) Top Right - Mrs. Stoneman Captain Myles W. Keogh (?) Bottom Left - William Price Sanders A. Hand Bottom Right Unidentified man Dr. E. W. H. Beck Page 1 (back page): Page 5: Mrs. Coolidge Mrs. John Buford Dr. Richard Coolidge John Buford Phillip St. George Cooke J. Duke Buford Mrs. Phillip St. George Cooke Watson Buford Page 2: Page 5 (back page): John Cooke Captain Theodore Bacon (?) Sallie Buford Bell Unidentified man Julia Cooke Fanny Graddy (sp?) Unidentified woman George Gordon Meade Page 2 (back page): Page 6: John Gibbon Unidentified woman Gibbon children D. -

Lincoln's Role in the Gettysburg Campaign

LINCOLN'S ROLE IN THE GETTYSBURG CAMPAIGN By EDWIN B. CODDINGTON* MOST of you need not be reminded that the battle of Gettys- burg was fought on the first three days of July, 1863, just when Grant's siege of Vicksburg was coming to a successful con- clusion. On July 4. even as Lee's and Meade's men lay panting from their exertions on the slopes of Seminary and Cemetery Ridges, the defenders of the mighty fortress on the Mississippi were laying down their arms. Independence Day, 1863, was, for the Union, truly a Glorious Fourth. But the occurrence of these two great victories at almost the same time raised a question then which has persisted up to the present: If the triumph at Vicksburg was decisive, why was not the one at Gettysburg equally so? Lincoln maintained that it should have been, and this paper is concerned with the soundness of his supposition. The Gettysburg Campaign was the direct outcome of the battle of Chancellorsville, which took place the first week in May. There General Robert E. Lee won a victory which, according to the bookmaker's odds, should have belonged to Major General "Fight- ing Joe" Hooker, if only because Hooker's army outnumbered the Confederates two to one and was better equipped. The story of the Chancel'orsville Campaign is too long and complicated to be told here. It is enough to say that Hooker's initial moves sur- prised his opponent, General Lee, but when Lee refused to react to his strategy in the way he anticipated, Hooker lost his nerve and from then on did everything wrong. -

Sacred Ties: from West Point Brothers to Battlefield Rivals: a True Story of the American Civil War

Civil War Book Review Summer 2010 Article 12 Sacred Ties: From West Point Brothers to Battlefield Rivals: A True Story of the American Civil War Wayne Wei-siang Hsieh Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr Recommended Citation Hsieh, Wayne Wei-siang (2010) "Sacred Ties: From West Point Brothers to Battlefield Rivals: A True Story of the American Civil War," Civil War Book Review: Vol. 12 : Iss. 3 . Available at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr/vol12/iss3/12 Hsieh: Sacred Ties: From West Point Brothers to Battlefield Rivals: A Tr Review Hsieh, Wayne Wei-siang Summer 2010 Carhart, Tom Sacred Ties: From West Point Brothers to Battlefield Rivals: A True Story of the American Civil War. Berkley Caliber, 978-0-425-23421-1 ISBN 978-0-425-23421-1 Bonds of Brotherhood Tom Carhart, himself a West Point graduate and twice-wounded Vietnam veteran, has written a new study of the famous West Point Classes of 1860 and 1861. Carhart chooses to focus on four notable graduates from the Classes of 1861 (Henry Algernon DuPont, John Pelham, Thomas Lafayette Rosser, and George Armstrong Custer), and two from the Class of 1860 (Wesley Merritt and Stephen Dodson Ramseur). Carhart focuses on the close bonds formed between these cadets at West Point, which persisted even after the division of both the nation and the antebellum U.S. Army officer corps during the Civil War. He starts his narrative with a shared (and illicit) drinking party at Benny’s Haven, a nearby tavern and bane of the humorless guardians of cadet discipline at what is sometimes now not-so-fondly described as the South Hudson Institute of Technology. -

The Battle of Sailor's Creek

THE BATTLE OF SAILOR’S CREEK: A STUDY IN LEADERSHIP A Thesis by CLOYD ALLEN SMITH JR. Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2005 Major Subject: History THE BATTLE OF SAILOR’S CREEK: A STUDY IN LEADERSHIP A Thesis by CLOYD ALLEN SMITH JR. Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved by: Chair of Committee, Joseph Dawson Committee Members, James Bradford Joseph Cerami Head of Department, Walter L. Buenger December 2005 Major Subject: History iii ABSTRACT The Battle of Sailor’s Creek: A Study in Leadership. (December 2005) Cloyd Allen Smith Jr., B.A., Slippery Rock University Chair: Dr. Joseph Dawson The Battle of Sailor’s Creek, 6 April 1865, has been overshadowed by Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House several days later, yet it is an example of the Union military war machine reaching its apex of war making ability during the Civil War. Through Ulysses S. Grant’s leadership and that of his subordinates, the Union armies, specifically that of the Army of the Potomac, had been transformed into a highly motivated, organized and responsive tool of war, led by confident leaders who understood their commander’s intent and were able to execute on that intent with audacious initiative in the absence of further orders. After Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia escaped from Petersburg and Richmond on 2 April 1865, Grant’s forces chased after Lee’s forces with the intent of destroying the mighty and once feared iv protector of the Confederate States in the hopes of bringing a swift end to the long war. -

Episode 236: the End Unravels Week of April 12-April 18, 1865

Episode 236: The End Unravels Week of April 12-April 18, 1865 This podcast was written by Davis Gammon, student of history at Longwood University. The week of April 12, 1865 was not only one of the most consequential weeks of the Civil War, but also one of the most important in United States history. Contrary to popular belief, even as late as early 1865 there was hope in the South that the Confederacy might live. By April, however, all hope in the South was gone. Sherman had long ago marched to the sea, Lee had just surrendered at Appomattox Courthouse, and Confederate president, Jefferson Davis and the rest of the Confederate government fled to Danville, Virginia. Union general, Edward Canby, and his Federal forces dug in and were poised to capture the last major city in the Deep South, Mobile, Alabama. On April 12 the city fell into the control of the Union Army. Like many Confederate commanders before him, Virginian Dabney Maury left nothing in the city for the capturing Federals, burning cotton and other useful supplies. April 14, 1865 began in the North with such hope and celebration. Exactly four years earlier the United States Army had surrendered Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor to the newly rebelling Confederates. On this day four years later, there was a great celebration of remembrance and victory in Charleston. The event reached a crescendo when the flag of the United States was once again flying above the once defeated battery. With the demise of the Army of Northern Virginia, the advance of Sherman up the Atlantic coast, and the fall of the last Deep South stronghold, Mobile, President Lincoln looked to establish a post-war reconstruction policy that would bring the South back into the Union in an orderly fashion. -

Arlington National Cemetery Ord and Weitzel Gate Relocation

Arlington National Cemetery Ord and Weitzel Gate Relocation _______________ Submitted by the Department of the Army, Army National Cemeteries Concept Review Project Information Commission meeting date: September 4, 2015 NCPC review authority: 40 USC 8722 (b)(1) Applicant request: concept design review Delegated / consent / open / executive session: delegated NCPC Review Officer: Hart NCPC File number: 7708 Project summary: The Army submitted a proposal to relocate a gate at Arlington National Cemetery. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, this gate was one of the main entrances into the cemetery. This gate is comprised of two columns that were taken from the north portico of the neoclassical War Department buildings that once stood next to the White House. These buildings were constructed between 1818 and 1820, but were scheduled for demolition in 1879 to make way for the Old Executive Office Building. Brigadier General Montgomery Meigs arranged to have the stonework and columns removed and reinstalled in Arlington Cemetery. Army Corps of Engineers provided plans and specs for two new gateways based on Meigs design. These became the Ord and Weitzel Gate and the Sheridan Gate. Major General Edward Ord was an American engineer and United States Army officer who saw action in the Seminole War, the Indian Wars, and the American Civil War. He commanded an army during the final days of the Civil War, and was instrumental in forcing the surrender of Confederate General Robert E. Lee. He also designed Fort Sam Houston. He died in Havana, Cuba of Yellow fever. (Wikipedia) Major General Godfrey Weitzel was in the Union Army during the American Civil War, as well as the acting Mayor of New Orleans during the Union occupation of the city.