CH3.PDF (79.23Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Although Topology Was Recognized by Gauss and Maxwell to Play a Pivotal Role in the Formulation of Electromagnetic Boundary Valu

Although topology was recognized by Gauss and Maxwell to play a pivotal role in the formulation of electromagnetic boundary value problems, it is a largely unexploited tool for field computation. The development of algebraic topology since Maxwell provides a framework for linking data structures, algorithms, and computation to topological aspects of three-dimensional electromagnetic boundary value problems. This book attempts to expose the link between Maxwell and a modern approach to algorithms. The first chapters lay out the relevant facts about homology and coho- mology, stressing their interpretations in electromagnetism. These topological structures are subsequently tied to variational formulations in electromagnet- ics, the finite element method, algorithms, and certain aspects of numerical linear algebra. A recurring theme is the formulation of and algorithms for the problem of making branch cuts for computing magnetic scalar potentials and eddy currents. An appendix bridges the gap between the material presented and standard expositions of differential forms, Hodge decompositions, and tools for realizing representatives of homology classes as embedded manifolds. Mathematical Sciences Research Institute Publications 48 Electromagnetic Theory and Computation A Topological Approach Mathematical Sciences Research Institute Publications 1 Freed/Uhlenbeck: Instantons and Four-Manifolds, second edition 2 Chern (ed.): Seminar on Nonlinear Partial Differential Equations 3 Lepowsky/Mandelstam/Singer (eds.): Vertex Operators in Mathematics and -

Mechanical Ventilation

Fundamentals of MMeecchhaanniiccaall VVeennttiillaattiioonn A short course on the theory and application of mechanical ventilators Robert L. Chatburn, BS, RRT-NPS, FAARC Director Respiratory Care Department University Hospitals of Cleveland Associate Professor Department of Pediatrics Case Western Reserve University Cleveland, Ohio Mandu Press Ltd. Cleveland Heights, Ohio Published by: Mandu Press Ltd. PO Box 18284 Cleveland Heights, OH 44118-0284 All rights reserved. This book, or any parts thereof, may not be used or reproduced by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review. First Edition Copyright 2003 by Robert L. Chatburn Library of Congress Control Number: 2003103281 ISBN, printed edition: 0-9729438-2-X ISBN, PDF edition: 0-9729438-3-8 First printing: 2003 Care has been taken to confirm the accuracy of the information presented and to describe generally accepted practices. However, the author and publisher are not responsible for errors or omissions or for any consequences from application of the information in this book and make no warranty, express or implied, with respect to the contents of the publication. Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION TO VENTILATION..............................1 Self Assessment Questions.......................................................... 4 Definitions................................................................................ -

An Introduction to the Ontology of Physics for Biology

Physical Properties of Biological Entities: An Introduction to the Ontology of Physics for Biology Daniel L. Cook1,2,3*, Fred L. Bookstein4,5, John H. Gennari3 1 Department of Physiology and Biophysics, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, United States of America, 2 Department of Biological Structure, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, United States of America, 3 Division of Biomedical and Health Informatics, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, United States of America, 4 Department of Statistics, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, United States of America, 5 Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria Abstract As biomedical investigators strive to integrate data and analyses across spatiotemporal scales and biomedical domains, they have recognized the benefits of formalizing languages and terminologies via computational ontologies. Although ontologies for biological entities—molecules, cells, organs—are well-established, there are no principled ontologies of physical properties—energies, volumes, flow rates—of those entities. In this paper, we introduce the Ontology of Physics for Biology (OPB), a reference ontology of classical physics designed for annotating biophysical content of growing repositories of biomedical datasets and analytical models. The OPB’s semantic framework, traceable to James Clerk Maxwell, encompasses modern theories of system dynamics and thermodynamics, and is implemented as a computational ontology that references available upper ontologies. In this paper we focus on the OPB classes that are designed for annotating physical properties encoded in biomedical datasets and computational models, and we discuss how the OPB framework will facilitate biomedical knowledge integration. Citation: Cook DL, Bookstein FL, Gennari JH (2011) Physical Properties of Biological Entities: An Introduction to the Ontology of Physics for Biology. -

Voltage Transients in the Field Winding of Salient Pole Wound Synchronous Machines Implications from Fast Switching Power Electronics

Voltage Transients in the Field Winding of Salient Pole Wound Synchronous Machines Implications from fast switching power electronics Roberto Felicetti Licentiate thesis to be presented at Uppsala University, Häggsalen 10132, Ångströmlaboratoriet, Lägerhyddsvägen 1, Uppsala, Friday, 12 March 2021 at 10:00. The examination will be conducted in English. Abstract Felicetti, R. 2021: Voltage Transients in the Field Winding of Salient Pole Wound Synchro- nous Machines: Implications from fast switching power electronics. 91 pp. Uppsala. Wound Field Synchronous Generators provide more than 95% of the electricity need world- wide. Their primacy in electricity production is due to ease of voltage regulation, performed by simply adjusting the direct current intensity in their rotor winding. Nevertheless, the rapid progress of power electronics devices enables new possibilities for alternating current add-ins in a more than a century long DC dominated technology. Damping the rotor oscillations with less energy loss than before, reducing the wear of the bearings by actively compensating for the mechanic unbalance of the rotating parts, speeding up the generator with no need for additional means, these are just few of the new applications which imply partial or total alter- nated current supplying of the rotor winding. This thesis explores what happens in a winding traditionally designed for the direct current supply when an alternated current is injected into it by an inverter. The research focuses on wound field salient pole synchronous machines and investigates the changes in the field wind- ing parameters under AC conditions. Particular attention is dedicated to the potentially harm- ful voltage surges and voltage gradients triggered by voltage-edges with large slew rate. -

On Electrostatic Transformers and Coupling Coefficients.1

On Electrostatic Transformers and Coupling Coefficients.1 BY F. C. BLAKE Physical Laboratory, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio. Starting from the experimentally determined fact that the capacity of an air condenser is independent of the fre quency of electrical oscillation, it is shown by means of Lord Rayleigh's equations for the mutual reaction between two circuits each having inductance, resistance, and capacity, that for high-frequency conditions when the resistance is negligible compared to the reactance, the capacity reaction between the two circuits can be expressed best in terms of elast- ances. Definitions are given for self and mutual elastances as well as for self and mutual capacitances and the definitions are tested by our knowledge of spherical condensers. The coefficient of elastic coupling is shown to be the ratio between the mutual elastance and the square root of the product of the two self elastances, the analogy with the coefficient of inductive coupling being exact. The coefficient of capacitive coupling between two circuits each having capacity with a capacity in the branch common to both is shown to be a limiting case of the coefficient of elastic coupling, and thereby a condenser of the ordinary or close form is shown to be an electrostatic transformer with a coupling coefficient of unity. The true relationship between Maxwell's coefficients of capacity and the elastances or capacitances is pointed out in the case of the spherical condenser. The ideas developed are applied to the thermionic tube and thereby the behavior of the ultraudion and the experiments of Van der Pol are readily explained. -

Electromagnetism II, Quiz 2

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Physics Department Physics 8.07: Electromagnetism II November 15, 2012 Prof. Alan Guth QUIZ 2 Reformatted to Remove Blank Pages∗ THE FORMULA SHEETS ARE AT THE END OF THE EXAM. Problem Maximum Score 1 25 2 35 3 20 Your Name Recitation 4 10 5 10 TOTAL 100 ∗ A few clarifications that were posted on the blackboard during the quiz are incorpo- rated here into the text. 8.07 QUIZ 2, FALL 2012 p. 2 PROBLEM 1: THE MAGNETIC FIELD OF A SPINNING, UNIFORMLY CHARGED SPHERE (25 points) This problem is based on Problem 1 of Problem Set 8. A uniformly charged solid sphere of radius R carries a total charge Q,andisset spinning with angular velocity ω about the z axis. (a) (10 points) What is the magnetic dipole moment of the sphere? (b) (5 points) Using the dipole approximation, what is the vector potential A(r)atlarge distances? (Remember that A is a vector, so it is not enough to merely specify its magnitude.) (c) (10 points) Find the exact vector potential INSIDE the sphere. You may, if you wish, make use of the result of Example 5.11 from Griffiths’ book. There he considered a spherical shell, of radius R, carrying a uniform surface charge σ, spinning at angular velocity ω directed along the z axis. He found the vector potential µ0Rωσ r sin θ φ,ˆ (if r ≤ R) 3 A(r, θ, φ)= 4 (1.1) µ0R ωσ sin θ φ,ˆ (if r ≥ R). 3 r2 PROBLEM 2: SPHERE WITH VARIABLE DIELECTRIC CONSTANT (35 points) A dielectric sphere of radius R has variable permittivity, so the permittivity throughout space is described by 2 0(R/r) if r<R ( r)= (2.1) 0 , if r>R. -

Dynamical Properties of Electrical Circuits with Fully Nonlinear Memristors

Dynamical properties of electrical circuits with fully nonlinear memristors∗ Ricardo Riaza Departamento de Matem´atica Aplicada a las Tecnolog´ıas de la Informaci´on Escuela T´ecnica Superior de Ingenieros de Telecomunicaci´on Universidad Polit´ecnica de Madrid - 28040 Madrid, Spain [email protected] Abstract The recent design of a nanoscale device with a memristive characteristic has had a great impact in nonlinear circuit theory. Such a device, whose existence was predicted by Leon Chua in 1971, is governed by a charge-dependent voltage-current relation of the form v = M(q)i. In this paper we show that allowing for a fully nonlinear charac- teristic v = η(q, i) in memristive devices provides a general framework for modeling and analyzing a very broad family of electrical and electronic circuits; Chua’s memristors are particular instances in which η(q, i) is linear in i. We examine several dynamical features of circuits with fully nonlinear memristors, accommodating not only charge- controlled but also flux-controlled ones, with a characteristic of the form i = ζ(ϕ, v). Our results apply in particular to Chua’s memristive circuits; certain properties of these can be seen as a consequence of the special form of the elastance and reluctance matrices displayed by Chua’s memristors. arXiv:1008.2528v1 [math.DS] 15 Aug 2010 Keywords: nonlinear circuit, memristor, differential-algebraic equation, semistate model, state dimension, eigenvalues. AMS subject classification: 05C50, 15A18, 34A09, 94C05. ∗Supported by Research Project MTM2007-62064 (MEC, Spain). 1 1 Introduction In 1971 Leon Chua predicted the existence of a fourth basic circuit element which would be governed by a flux-charge relation, having either a charge-controlled form ϕ = φ(q) or a flux- controlled one q = σ(ϕ) [10]. -

Electrical Impedance Tomography for Cardio-Pulmonary Monitoring

Journal of Clinical Medicine Review Electrical Impedance Tomography for Cardio-Pulmonary Monitoring Christian Putensen 1,*, Benjamin Hentze 1,2 , Stefan Muenster 1 and Thomas Muders 1 1 Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine, University Hospital Bonn, 53127 Bonn, Germany 2 Chair for Medical Information Technology, RWTH Aachen University, 52074 Aachen, Germany * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-228-287-14118 Received: 28 June 2019; Accepted: 6 August 2019; Published: 7 August 2019 Abstract: Electrical impedance tomography (EIT) is a bedside monitoring tool that noninvasively visualizes local ventilation and arguably lung perfusion distribution. This article reviews and discusses both methodological and clinical aspects of thoracic EIT. Initially, investigators addressed the validation of EIT to measure regional ventilation. Current studies focus mainly on its clinical applications to quantify lung collapse, tidal recruitment, and lung overdistension to titrate positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) and tidal volume. In addition, EIT may help to detect pneumothorax. Recent studies evaluated EIT as a tool to measure regional lung perfusion. Indicator-free EIT measurements might be sufficient to continuously measure cardiac stroke volume. The use of a contrast agent such as saline might be required to assess regional lung perfusion. As a result, EIT-based monitoring of regional ventilation and lung perfusion may visualize local ventilation and perfusion matching, which can be helpful in the treatment of patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Keywords: electrical impedance tomography; bioimpedance; image reconstruction; thorax; regional ventilation; regional perfusion; monitoring 1. Introduction Electrical impedance tomography (EIT) is a radiation-free functional imaging modality that allows non-invasive bedside monitoring of both regional lung ventilation and arguably perfusion. -

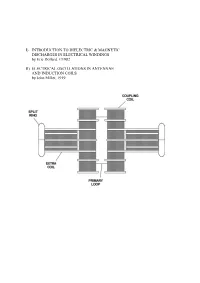

I) Introduction to Dielectric & Magnetic Discharges In

I) INTRODUCTION TO DIELECTRIC & MAGNETIC DISCHARGES IN ELECTRICAL WINDINGS by Eric Dollard, ©1982 II) ELECTRICAL OSCILLATIONS IN ANTENNAE AND INDUCTION COILS by John Miller, 1919 PART I INTRODUCTION TO DIELECTRIC & MAGNETIC DISCHARGES IN ELECTRICAL WINDINGS by Eric Dollard, ©1982 1. CAPACITANCE 2. CAPACITANCE INADEQUATELY EXPLAINED 3. LINES OF FORCE AS REPRESENTATION OF DIELECTRICITY 4. THE LAWS OF LINES OF FORCE 5. FARADAY'S LINES OF FORCE THEORY 6. PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF LINES OF FORCE 7. MASS ASSOCIATED WITH LINES OF FORCE IN MOTION 8. INDUCTANCE AS AN ANALOGY TO CAPACITANCE 9. MECHANISM OF STORING ENERGY MAGNETICALLY 10. THE LIMITS OF ZERO AND INFINITY 11. INSTANT ENERGY RELEASE AS INFINITY 12. ANOTHER FORM OF ENERGY APPEARS 13. ENERGY STORAGE SPATIALLY DIFFERENT THAN MAGNETIC ENERGY STORAGE 14. VOTAGE IS TO DIELECTRICITY AS CURRENT IS TO MAGNETISM 15. AGAIN THE LIMITS OF ZERO AND INFINITY 16. INSTANT ENERGY RELEASE AS INFINITY 17. ENERGY RETURNS TO MAGNETIC FORM 18. CHARACTERISTIC IMPEDANCE AS A REPRESENTATION OF PULSATION OF ENERGY 19. ENERGY INTO MATTER 20. MISCONCEPTION OF PRESENT THEORY OF CAPACITANCE 21. FREE SPACE INDUCTANCE IS INFINITE 22. WORK OF TESLA, STEINMETZ, AND FARADAY 23. QUESTION AS TO THE VELOCITY OF DIELECTRIC FLUX APPENDIX I 0) Table of Units, Symbols & Dimensions 1) Table of Magnetic & Dielectric Relations 2) Table of Magnetic, Dielectric & Electronic Relations PART II ELECTRICAL OSCILLATIONS IN ANTENNAE & INDUCTION COILS J.M. Miller Proceedings, Institute of Radio Engineers. 1919 1) CAPACITANCE The phenomena of capacitance is a type of electrical energy storage in the form of a field in an enclosed space. This space is typically bounded by two parallel metallic plates or two metallic foils on an interviening insulator or dielectric. -

Lung Impedance Measurements Using Tracked Breathing Daphtary Nirav University of Vermont

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM Graduate College Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 2010 Lung Impedance Measurements Using Tracked Breathing Daphtary Nirav University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis Recommended Citation Nirav, Daphtary, "Lung Impedance Measurements Using Tracked Breathing" (2010). Graduate College Dissertations and Theses. 162. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis/162 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate College Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LUNG IMPEDANCE MEASUREMENTS USING TRACKED BREATHING A Thesis Presented by Nirav Daphtary to The Faculty of the Graduate College of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Specializing in Biomedical Engineering May 2010 Accepted by the Faculty of the Graduate College, The University of Vermont, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science specializing in Biomedical Engineering. Thesis Examination Committee: Advisor - Lennart Lundblad, Ph.D. - Chairperson Dean, Graduate College Date: March 24,2010 ABSTRACT The forced Oscillation Technique (FOT) can be used to measure lung impedance continuously during breathing. However, spectral overlap between the breathing waveform and the applied flow oscillation can be problematic if the frequency content of spontaneous breathing is unknown. This problem motivated us to develop a modification to the FOT system called the Tracked Breathing Trainer. The modification uses biofeedback to constrain subjects to breathe at a single predetermined frequency. -

Multi-Scale Cardiovascular Flow Analysis by an Integrated Meshless-Lumped Parameter Model

L. A. Bueno, et al., Int. J. Comp. Meth. and Exp. Meas., Vol. 6, No. 6 (2017) 1138–1148 MULTI-SCALE CARDIOVASCULAR FLOW ANALYSIS BY AN INTEGRATED MESHLESS-LUMPED PARAMETER MODEL LEONARDO A. BUENO1, EDUARDO A. DIVO1 & ALAIN J. KASSAB2 1Department of Mechanical Engineering, Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, Daytona Beach, FL, USA. 2Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, University of Central Florida, Orlando, FL, USA. ABSTRACT A computational tool that integrates a Radial basis function (RBF)-based Meshless solver with a Lumped Parameter model (LPM) is developed to analyze the multi-scale and multi-physics interaction between the cardiovascular flow hemodynamics, the cardiac function, and the peripheral circulation. The Mesh- less solver is based on localized RBF collocations at scattered data points which allows for automation of the model generation via CAD integration. The time-accurate incompressible flow hemodynamics are addressed via a pressure-velocity correction scheme where the ensuing Poisson equations are accurately and efficiently solved at each time step by a Dual-Reciprocity Boundary Element method (DRBEM) formulation that takes advantage of the integrated surface discretization and automated point distribution used for the Meshless collocation. The local hemodynamics are integrated with the peripheral circulation via compartments that account for branch viscous resistance (R), flow inertia (L), and vessel compliance (C), namely RLC electric circuit analogies. The cardiac function is modeled via time-varying capacitors simulating the ventricles and constant capacitors simulating the atria, connected by diodes and resistors simulating the atrioventricular and ventricular-arterial valves. This multi-scale integration in an in-house developed computational tool opens the possibility for model automation of patient-specific anatomies from medical imaging, elastodynamics analysis of vessel wall deformation for fluid-structure interaction, automated model refinement, and inverse analysis for parameter estimation. -

2Quasistatic Electromagnetic Fields

May one plow with an ox and an ass together? The like of you may write everything and prove everything in quaternions, but in the transition period the bilingual method may help to explain the more perfect. James Clerk Maxwell, in a letter to P. G. Tait. 2Quasistatic Electromagnetic Fields The purpose of this chapter is to articulate the notion of a quasistatic elec- tromagnetic system, and develop the topological aspects of the boundary value problems encountered in the analysis of quasistatic systems. The topological ap- proach gives a new perspective on variational formulations which form the basis of finite element analysis. 2A. The Quasistatic Limit Of Maxwell's Equations Maxwell's Equations. Let S be a surface with boundary, V a volume in R3, and note that @ denotes the boundary operator. The integral versions of Maxwell's equations are as follows: d (2{1) E dl = B dS (Faraday's Law) · −dt · Z@S ZS (2{2) B dS = 0 (Gauss' Law for magnetic charge) 0 · Z@V d (2{3) H dl = D dS + J dS (Amp`ere's Law) 0 · dt 0 · 0 · Z@S ZS ZS (2{4) D dS = ρ dV (Gauss' Law) · Z@V ZV where E = Electric field intensity vector; B = Magnetic field flux density vector; H = Magnetic field intensity vector; D = Electric field flux density vector; 49 50 2. QUASISTATIC ELECTROMAGNETIC FIELDS and the current and charge sources are described by J = Electric current flux density vector; ρ = Electric charge density. If we let S0 = @V in Amp`ere's Law (2{3) and remember that @@ = 0, then the field vector can be eliminated between Amp`ere's and Gauss' law, (2{3) and (2{4) to reveal a statement of charge conservation: d 0 = ρ dV + J dS: dt · ZV Z@V This shows that conservation of charge is implicit in Maxwell's equations.