P. and Society. MI

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POP Library SUBJECT LIST 12/11/2010

POP Library SUBJECT LIST 12/11/2010 Subject Title Author Location Addictions Narcotics Anonymous World Service 613.8 Ser Adolescents The Secret Survival Manual J.Brent Bill J 155.5 Bil Group Growers Lane Eskew 155.5 Esk Help! I'm A Volunteer Youth Worker! Doug Fields 155.5 Fie Group's Best Jr. High Meetings Cindy Parolini 155.5 Par Adult Education Llifelong Learning Rebecca Grothe 374 Gro Starting Small Groups - And Keeping Them George S Johnson 374 Joh Advent The Jesse Tree Anderson, Raymond And Georgene 263 And Jesse Tree Devotions Marilyn Breckenridge 263 Bre Unto Us Is Born Herbert Brookering 242 Bro Unto Us Is Born Herbert F. Brookering 242.2 Bro Prepare Ye For A New Advent Of God's Love John And Adrian Carr 263 Car The Comings Of God Richard Simon Hanson 263 Han Advent Landmarks Robert Hershey 263 Her Advent Paul M. Lindberg 263 Lin What Child Is This? Samuel H. Miller 263 Mil Won't You Let Him In? James W. Moore 242.3 Mor Family Countdown To Christmas Debbie Trafton O'Neal 263 O'Ne Celebrate Jesus At Christmas Kimberly Ingalls Reese 394 Ree Lighted Windows Margaret Silf 263 Sil Countdown To Christmas Zimmerman, Laura K. E. 263 Zim Advent / Christmas Destination Bethlehem Ann W. Anderson 263 And Come Lord Jesus Susan Briehl 242 Bri Day By Day In Advent Christopher G. Milarch 242 Mil Manger In The Mountains James Arne Nestingen 242 Nes Age Groups New Passages Gail Sheehy 305.2 She Aging Coming Of Age Gracefully Aid Association For Lutherans 155.7 AAL Home Sweet Home Aid Association For Lutherans 362.6 Hom Fullness Of Time Martha Whitmore Hickman 155.6 Hic Caring For Aging Parents Richard P. -

From Award Winning Comedy Showroom Pilot to Full Series the Letdown Starts Production

Released: Friday 16 June 2017 From Award Winning Comedy Showroom Pilot to Full Series The Letdown starts production Production has commenced on the six-part comedy series The Letdown, for ABC in Australia and Netflix internationally with funding support from Screen Australia in association with Create NSW. ABC will broadcast the series in Australia on TV and iview. Netflix will stream the series internationally outside of Australia, and it will be available on Netflix in Australia after its run on ABC. Produced by Giant Dwarf and co-written by Sarah Scheller and Alison Bell, who also stars, The Letdown was one of six Comedy Showroom pilots which aired last year on ABC TV as part of a joint initiative with Screen Australia. With the pilot episode receiving the 2016 AACTA Award for Best Screenplay in Television, the series continues with the developing friendships and lives of a mother's group thrown together through the circumstance of timing. Audrey (Alison Bell) navigates the steep learning curve of motherhood as she deals with sleeplessness, shifting relationship dynamics, her issues with her own mother and her husband's career ambitions. They say it takes a tribe to raise a child, but these days obliging tribes are hard to come by – so perhaps this unlikely group of women (and one fella) is as good as it gets. With a stellar cast including Alison Bell, Duncan Fellows, Sacha Horler, Leon Ford, Lucy Durack, Celeste Barber, Leah Vandenberg, Xana Tang, Sarah Peirse and Noni Hazelhurst, The Letdown proves that being a parent can be both extreme and hilarious. -

The Advertiser Deserves the Money Will Most Likely Be for New (Tuesday, October 20)

T S G E: [email protected] Ph: 5461-3866 www.maryboroughadvertiser.com.au www.maryboroughbusiness.com.au Published Tuesdays & Fridays No. 20,426 $1.50 c n i T HEALTH T COUNCIL T MDCA HEALTH SERVICE APPOINTS NEW CEO BROILER FARM APPLICATION HEADED TO COUNCIL MARYBOROUGH AND AVOCA UNITE FOR 2020/21 PAGE 3 PAGE 5 SPORT The Maryborough District AdvertiserEst. 1855 Tuesday, October 20, 2020 CAUTIONARY TALE Holly and Rolly the beagles have been Brian Smithʼs closest companions for some time now, after his wife Sandy passed away 18 months ago. The tight knit trio have endured a lot together, including Rollyʼs run in with a brown snake earlier this month — the first confirmed bite for the season and sparking an emergency trip to the vet. Story, Page 7. SMALL STEPS201020 04 Household bubble removed as Premier announces minor changes to COVID restrictions CHRISTIE HARRISON Third Step restrictions, residents are “It’s not so long ago that we had then to find that normal and begin Wednesday last week. Regional Victoria took another now able to host two visitors from 725 cases and there was simply no the process of rebuilding. Four new cases were recorded as step towards reopening at the two households per day at home, and way we could have a debate about “Yes, these lockdowns have come of the latest figures on Monday, and weekend with minor changes to patron limits have been increased for how and when to open,” Mr Andrews with significant hurt and pain and one life was lost to the virus. -

Presentación

MONOGRÁFICO Investigaciones Feministas ISSNe: 2171-6080 https://dx.doi.org/10.5209/infe.66489 Presentación Graciela Padilla Castillo1 Es un placer poder presentar este número temático de la revista Investigaciones Fe- ministas de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid por muchas razones, que inten- taré resumir en las líneas siguientes. En primer lugar, es un orgullo ver materializado un número temático sobre un tema que tanto me llena y me apasiona, como profesora, investigadora y ciudadana. Las series de televisión me cautivaron desde que mi memoria alcanza y han llenado mi ocio y después, mi profesión. En clase, me han permitido acercarme a mis estu- diantes, curso tras curso, con excelentes resultados. Ver las series que yo elegía y las series que ellos y ellas me recomendaban nos hacía aprender con solidez, ejempli- ficar con tenacidad la teoría de clase y hablar el mismo lenguaje. Por esas razones llevaba muchos años afirmando la necesidad de dejar demonizar la televisión, preci- samente por la altísima calidad de la ficción televisiva. El auge de las plataformas de vídeo bajo demanda hizo que esa idea, por fin, fuera compartida a gran escala y la nueva edad de oro de la ficción televisiva ha diluido esas voces que castigaban todo lo que salía en la pequeña pantalla. Vivimos una época histórica de ficción televisiva, con millones de espectadores acérrimos en todo el mundo. Es verdad que no es la primera vez que ocurre: ha habido otros momentos históricos, de grandes éxitos televisivos, que inventaron y reinventaron formatos y géneros, que son la base de muchas series que vemos ahora. -

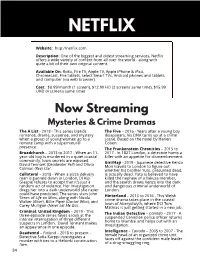

British TV Streaming Guide

NETFLIX Website: http://netflix.com Description: One of the biggest and oldest streaming services, Netflix offers a wide variety of content from all over the world - along with quite a bit of their own original content. Available On: Roku, Fire TV, Apple TV, Apple iPhone & iPad, Chromecast, Fire tablets, select Smart TVs, Android phones and tablets, and computer (via web browser). Cost: $8.99/month (1 screen), $12.99 HD (2 screens same time), $15.99 UHD (4 screens same time) Now Streaming Mysteries & Crime Dramas The A List - 2018 - This series blends The Five – 2016 - Years after a young boy romance, drama, suspense, and mystery disappears, his DNA turns up at a crime when a group of young women go to a scene. Based on the novel by Harlen remote camp with a supernatural Coben. presence. The Frankenstein Chronicles – 2015 to Broadchurch – 2013 to 2017 - When an 11- 2017 - In 1827 London, a detective hunts a year-old boy is murdered in a quiet coastal killer with an appetite for dismemberment. community, town secrets are exposed. Giri/Haji - 2019 - Japanese detective Kenzo David Tennant (Deadwater Fell) and Olivia Mori travels to London to figure out Colman (Rev) star. whether his brother Yuto, presumed dead, Collateral – 2018 - When a pizza delivery is actually dead. Yuto is believed to have man is gunned down in London, DI Kip killed the nephew of a Yakuza member, Glaspie refuses to accept that it's just a and the search draws Kenzo into the dark random act of violence. Her investigation and dangerous criminal underworld of drags her into a dark underworld she never London. -

Squinters Media Release

RELEASED: Thursday 12th October, 2017 Stars come out for new ABC comedy Squinters ABC and Screen Australia in association with Create NSW are pleased to announce that filming is underway in Sydney this week on Jungle’s new six-part comedy series Squinters, a series that celebrates the great Aussie ritual that is the everyday work commute. An extraordinary ensemble cast includes beloved performer/composer Tim Minchin, Academy-Award nominee Jacki Weaver, Miranda Tapsell, Mandy McElhinney, Damon Herriman, Sam Simmons, Andrea Demetriades, Wayne Blair, Christiaan Van Vuuren, Justin Rosniak and Jenna Owen, along with young comic talents Susie Youssef (Rosehaven), Rose Matafeo (NZ’s Funny Girls), Steen Raskopoulos (BBC’s Top Coppers), YouTube sensation John Luc (aka ‘MyChonny’) as well as the UK’s Nyasha Hatendi (Hulu’s Casual). Created by Trent O’Donnell (The Moodys, No Activity) and Adam Zwar (Wilfred, Lowdown), Squinters tracks the trials and tribulations of five carloads of travelers in peak hour morning transit and again on their drive home to find out how the workday turned out. Our commuters include: a dispatch driver hoping to win the woman of his dreams by carpooling her to work; a single mum keen to avoid her teen daughter making the same mistakes in love, while juggling a new romance of her own; a clueless ex- school bully hitching a ride with the guy he tormented; best girlfriends whose friendship is tested when one becomes the other’s unlikely boss; and a newly ‘out’, middle-aged man grappling with both possible redundancy and a recalcitrant dog. Squinters’ behind the scenes creative team is also compelling. -

Cameras Roll on the Letdown Season Two

Released: Thursday 25 October 2018 Cameras Roll On The Letdown Season Two ABC, Screen Australia and Create NSW are thrilled to announce that filming starts in Sydney next week on the highly anticipated season two of the AACTA Award-winning comedy The Letdown. Produced by Julian Morrow (The Checkout, The Chaser’s War on Everything) and Linda Micsko (Maximum Choppage, Laid) for Giant Dwarf, creators/writers Sarah Scheller and Alison Bell once again mine the myriad humorous highs and heartbreaking lows faced by new mothers. Over six new episodes, we continue to follow the story of Audrey (co-creator Alison Bell, in her AACTA Award-nominated role) and the local Mothers’ Group she thought she didn’t need. The new season starts with all the babies turning one, where life with child has become the new norm and Audrey finally feels she’s mastering motherhood and life…but is she? Following on from the acclaimed 2016 Comedy Showroom series pilot, which earned Scheller and Bell the AACTA Award for Best Screenplay in Television, season one of The Letdown was a major critical and audience success on ABC (especially among 25-34 and 35-49 year old viewers), and outside Australia on Netflix, leading the show to earn international plaudits including a New York Times’ Arts Section cover story, and praise from Vanity Fair as a “clear-eyed take on parenthood, told hilariously”. Co-creators and writers Sarah Scheller and Alison Bell said, “We are thrilled to be back in production with the ABC and Netflix on another season of The Letdown because it turns out we have many more stories to tell.. -

Moving Forward in the Church

From My Bible-Sermon Notes & Outlines 2 From My Bible-Sermon Notes & Outlines Introduction These messages are compiled from study notes and outlines of my own and many others. I hope they are a help to you. I’m sure that all of us have at times “borrowed” or “used” a sermon we heard or read somewhere along the way. A thought, a word, or an idea jumped out to us from another preacher and we took that thing and ran with it. You have probably used an outline from a preacher brother but ended up preaching something that was uniquely different. Same idea, it just came out differently when you preached. Using your own thoughts, experiences, and illustrations……...the message became your own. I heard an old-time preacher once say, "Any message worth preaching ought to be worth preaching again!" Well, I have certainly preached some sermons again and again. I have borrowed from others to preach theirs again too. Please use these messages as the Lord leads and preach His Word over and over again! I make no claim of complete originality for this material. Also, please remember that these messages are not expected to substitute for your own personal study of the Word of God! The thoughts and ideas are given as a catalyst to help begin your ideas on a given passage of Scripture or trigger a seed thought to get you going. It is my prayer that the "stuff" contained here will further kindle the fire of God's message that is already in your heart. -

By Virginia Woolf

THE WAVES by Virginia Woolf The sun had not yet risen. The sea was indistinguishable from the sky, except that the sea was slightly creased as if a cloth had wrinkles in it. Gradually as the sky whitened a dark line lay on the horizon dividing the sea from the sky and the grey cloth became barred with thick strokes moving, one after another, beneath the surface, following each other, pursuing each other, perpetually. As they neared the shore each bar rose, heaped itself, broke and swept a thin veil of white water across the sand. The wave paused, and then drew out again, sighing like a sleeper whose breath comes and goes unconsciously. Gradually the dark bar on the horizon became clear as if the sediment in an old wine-bottle had sunk and left the glass green. Behind it, too, the sky cleared as if the white sediment there had sunk, or as if the arm of a woman couched beneath the horizon had raised a lamp and flat bars of white, green and yellow spread across the sky like the blades of a fan. Then she raised her lamp higher and the air seemed to become fibrous and to tear away from the green surface flickering and flaming in red and yellow fibres like the smoky fire that roars from a bonfire. Gradually the fibres of the burning bonfire were fused into one haze, one incandescence which lifted the weight of the woollen grey sky on top of it and turned it to a million atoms of soft blue. -

By Production

Strictly embargoed until 10.45pm AEDT Wednesday 7 December 2016 6TH AACTA AWARDS PRESENTED BY FOXTEL All Winners – by Production TELEVISION THE BEAUTIFUL LIE – 9 Nominations, 1 Win AACTA Award for Best Telefeature or Mini Series AACTA Award for Best Lead Actress in a Television Drama – Sarah Snook AACTA Award for Best Guest or Supporting Actress in a Television Drama – Celia Pacquola (Episode 3) AACTA Award for Best Screenplay in Television (Episode 3) AACTA Award for Best Cinematography in Television (Episode 3) AACTA Award for Best Editing in Television (Episode 6) AACTA Award for Best Sound in Television (Episode 6) AACTA Award for Best Production Design in Television (Episode 3) AACTA Award for Best Costume Design in Television (Episode 3) THE KETTERING INCIDENT – 8 Nominations, 3 Wins AACTA Award for Best Telefeature or Mini Series AACTA Award for Best Lead Actress in a Television Drama – Elizabeth Debicki AACTA Award for Best Guest or Supporting Actress in a Television Drama – Sacha Horler (Episode 3) AACTA Award for Best Guest or Supporting Actress in a Television Drama – Sianoa Smit- McPhee (Episode 1) AACTA Award for Best Direction in a Television Drama or Comedy (Episode 1) AACTA Award for Best Screenplay in Television (Episode 1) AACTA Award for Best Cinematography in Television (Episode 3) AACTA Award for Best Original Music Score in Television (Episode 1) RAKE – 7 Nominations, 2 Wins AACTA Award for Best Television Drama Series AACTA Award for Best Lead Actor in a Television Drama – Richard Roxburgh AACTA -

Australian Content in SVOD Catalogs: Availability and Discoverability 2018 Edition

Australian content in SVOD catalogs: availability and discoverability 2018 edition Authors: Dr Ramon Lobato and Alexa Scarlata School of Media and Communication, RMIT University Building 9, Bowen St, Melbourne VIC 3000 Email: [email protected] | [email protected] Tel: (03) 9925 3680 About the authors Dr Ramon Lobato is Senior Research Fellow in RMIT’s School of Media and Communication. A media industries scholar, Ramon has published several books on screen distribution including Netflix Nations (forthcoming from New York University Press), Shadow Economies of Cinema: Mapping Informal Film Distribution (British Film Institute, 2012) and Geoblocking and Global Video Culture (Institute of Network Cultures 2016, ed. with Meese), as well as more than 30 book chapters and articles. Ramon co-leads the Global Internet TV Research Consortium (www.global-internet-tv.com). Alexa Scarlata is a tutor and research assistant at RMIT and a PhD candidate in the School of Culture and Communication at the University of Melbourne. Her research interests include the informal and digital distribution of video content, media piracy and the political economy of transnational television programming. Her doctoral research examines the take-up of internet-distributed television in Australia and its impact on broadcast and subscription industries, particularly scripted television production. Alexa is a Research Fellow at the Networked Society Institute and on the editorial board of the International Journal of Digital Television. This report is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Page 1 of 11 Introduction Subscription video-on-demand (SVOD) portals are a new and disruptive category of entertainment service. -

Lost Silent Feature Films

List of 7200 Lost U.S. Silent Feature Films 1912-29 (last updated 11/16/16) Please note that this compilation is a work in progress, and updates will be posted here regularly. Each listing contains a hyperlink to its entry in our searchable database which features additional information on each title. The database lists approximately 11,000 silent features of four reels or more, and includes both lost films – 7200 as identified here – and approximately 3800 surviving titles of one reel or more. A film in which only a fragment, trailer, outtakes or stills survive is listed as a lost film, however “incomplete” films in which at least one full reel survives are not listed as lost. Please direct any questions or report any errors/suggested changes to Steve Leggett at [email protected] $1,000 Reward (1923) Adam And Evil (1927) $30,000 (1920) Adele (1919) $5,000 Reward (1918) Adopted Son, The (1917) $5,000,000 Counterfeiting Plot, The (1914) Adorable Deceiver , The (1926) 1915 World's Championship Series (1915) Adorable Savage, The (1920) 2 Girls Wanted (1927) Adventure In Hearts, An (1919) 23 1/2 Hours' Leave (1919) Adventure Shop, The (1919) 30 Below Zero (1926) Adventure (1925) 39 East (1920) Adventurer, The (1917) 40-Horse Hawkins (1924) Adventurer, The (1920) 40th Door, The (1924) Adventurer, The (1928) 45 Calibre War (1929) Adventures Of A Boy Scout, The (1915) 813 (1920) Adventures Of Buffalo Bill, The (1917) Abandonment, The (1916) Adventures Of Carol, The (1917) Abie's Imported Bride (1925) Adventures Of Kathlyn, The (1916) Ableminded Lady,