1 All Ears with Abigail Disney Episode 01: Terry Mcgovern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Girl Unbound

GIRL UNBOUND WORLD PREMIERE -- TIFF DOCS Screening Times: Sunday, September 11, 4:15pm//Scotiabank 3 Tuesday, September 13, 9:45pm// Scotiabank 10 Friday, September 16, 8:45pm//Scotiabank 13 Press and Industry Screening: Monday, September 12, 2:45pm // Scotiabank 6 Thursday, September 15, 2:30pm //Scotiabank 5 The following filmmakers and talent will be available for interviews: Erin Heidenreich (Director), Cassandra Sanford-Rosenthal, JonatHon Power (Producers) and Maria Toorpakai Wazir (film’s subject) Director: Erin Heidenreich Producers: Cassandra Sanford-Rosenthal, Jonathon Power Exec Producer: Abigail E. Disney, Gini Reticker, Cassandra Sanford-Rosenthal, Gary Slaight, Kerry Propper, George Kaufman, Elizabeth Bohart, Daniella Kahane Editor: Christina Burchard Cinematography: Mahera Omar, Nausheen Dadabhoy, Zeeshan Shafa, Talha Ahmed, Erin Heidenreich, Jerry Henry, Gareth Taylor, Matthias Schubert, Zev Starr-Tambor, Adrian Scartascini Featuring: Maria Toorpakai Wazir, Shamsul Qayyum Wazir, Ayesha Gulalai Wazir Runtime: 80 minutes Synopsis: In Waziristan, “one of the most dangerous places on earth”, Maria Toorpakai defies the Taliban - disguising herself as a boy, so she can play sports freely. But when she becomes a rising star, her true identity is revealed, bringing constant death threats on her and her family. Undeterred, they continue to rebel for their freedom. Press Contacts: PMK•BNC Alison Deknatel – [email protected] – 310.967.7247 Tiffany Olivares – [email protected] – 310.854.3272 Synopses GIRL UNBOUND: THE WAR TO BE HER Short synopsis: In Waziristan, “one of the most dangerous places on earth”, Maria Toorpakai defies the Taliban - disguising herself as a boy, so she can play sports freely. But when she becomes a rising star, her true identity is revealed, bringing constant death threats on her and her family. -

October 13, 2020

October 13, 2020 Robert A. Iger Executive Chairman and Chairman of the Board The Walt Disney Company 500 South Buena Vista Street Burbank, CA 91521 Bob Chapek Chief Executive Officer The Walt Disney Company 500 South Buena Vista Street Burbank, CA 91521 Dear Mr. Iger and Mr. Chapek: I write to express concern about The Walt Disney Company’s (Disney) recent decision to lay off 28,000 workers during an economic recession1 while reinstating pay rates for highly compensated senior executives.2 In the years leading up to this crisis, your company prioritized the enrichment of executives and stockholders through hefty compensation packages3, and billions of dollars’ worth of dividend payments4 and stock buybacks,5 all of which weakened Disney’s financial cushion and ability to retain and pay its front-line workers amid the pandemic. While I appreciate that your company has continued to provide health-care benefits to furloughed workers for the past six months,6 thousands of laid off employees will now have to worry about how to keep food on the table7 as executives begin receiving hefty paychecks again.8 I would like to know whether Disney’s financial decisions have impacted the company’s 1 Disney Parks, Experiences and Products, “Statement from Josh D’Amaro, Chairman, Disney Parks, Experiences and Products (DPEP),” September 29, 2020, https://dpep.disney.com/update/. 2 Deadline, “Disney & Fox Corporation End Temporary Executive Pay Cuts Related To COVID-19 Pandemic,” Nellie Andreeva and Dominic Patten, August 20, 2020, https://deadline.com/2020/08/disney-fox-coronavirus-pay- reductions-restored-1203018873/. -

All Ears with Abigail Disney Season 2 Episode 4: Anand Giridharadas Air Date: November 5, 2020

All Ears With Abigail Disney Season 2 Episode 4: Anand Giridharadas Air Date: November 5, 2020 ANAND GIRIDHARADAS: Hello? It's Anand here. ABIGAIL DISNEY: Hi how are you, good to hear from you. ANAND GIRIDHARADAS: Yes, likewise. Do you want me to record the audio locally? ABIGAIL DISNEY: Yeah. ANAND GIRIDHARADAS: Okay. So that's rolling also. ABIGAIL DISNEY: Good. It's high quality? ANAND GIRIDHARADAS: It's high quality. ABIGAIL DISNEY: Okay. Nothing but high quality will do for us. ANAND GIRIDHARADAS: Certainly higher quality than our democracy. ABIGAIL DISNEY: I hear that! I’m Abigail Disney. Welcome to All Ears, my podcast where I get to go deep with some super smart people. This season I’m talking to “good troublemakers:” artists, activists, politicians, and others, who aren’t afraid to shake up the status quo. We’ll talk about their work, how they came to do what they do, and and why it’s so important in hard times to think big. You can’t think about solutions without being a little optimistic and, man oh man, I think we need some optimism right now. So join me every Thursday for some good troublemaking. ABIGAIL DISNEY: Welcome to a special hot take edition of All Ears. We are recording on November 4th at 10:00 AM, which is a crazy day and a crazy time to try to do a show. Commonly held opinions and pollsters and pundits and neoliberal thought bubbles have failed us once again. No matter what the ultimate result of the count is to be, we know that. -

July 21 Press Release Final

! For Immediate Release Contact: Medea Benjamin Women Who Crossed Korean DMZ for Peace Brief Members of Congress July 20, 2015 (Washington, D.C.)—In May, 30 prominent women peacemakers from 15 countries, including two Nobel Peace Laureates, made a historic walk across the De-Mil- itarized Zone (DMZ) between North and South Korea calling for an end to the Korean War, family reunification, and women’s peacebuilding. They participated in peace sym- posia and walks with North and South Korean women where they learned about the im- pact of the unresolved Korean War on their lives. At a Congressional briefing co-spon- sored by Representatives John Conyers (D-MI) and Loretta Sanchez (D-CA), U.S. dele- gates will share insights from their journey across the Korean peninsula. 2015 marks the 70th anniversary of Korea’s arbitrary division into two separate states by the U.S. and former Soviet Union, which precipitated the 1950-53 Korean War. After claiming 4 million lives, including 36,000 U.S. troops, North Korea, China, and the United States signed the Armistice Agreement. Although the ceasefire halted the war, without a peace settlement, the Korean War still lives on and the DMZ stands in the way of the reunification of the Korean people and millions of families. 2015 also marks the 15th anniversary of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 which affirms the need for women’s involvement in all levels of peacebuilding. When: Tuesday, July 21, 2015, 4 pm Where: U.S. Congress Rayburn House Building 226 Who: Congressman John Conyers, Korean War Veteran Congressman Charles B. -

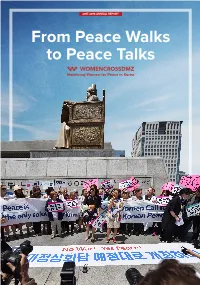

2017-2018 ANNUAL REPORT from Peace Walks to Peace Talks

2017-2018 ANNUAL REPORT From Peace Walks to Peace Talks Mobilizing Women for Peace in Korea LETTER FROM INTERNATIONAL COORDINATOR 2018 Steering Committee: Christine Ahn, International Coordinator Kozue Akibayashi, Women’s Int’l League for Peace & Freedom Aiyoung Choi, Nonprofit Management Consultant Dear Friends, Ewa Eriksson-Fortier, Retired Humanitarian Aid Worker Meri Joyce, Peace Boat, Global What a dramatic year it’s been. One year ago, Through talks, webinars, conferences, and the Partnership for the Prevention of Armed Conflict Northeast Asia President Donald Trump threatened to unleash media, we reached millions with our calls for Regional Coordinator “fire and fury” on North Korea. Now, the prospect peace and diplomacy. We rallied our partners Gwyn Kirk, Women for Genuine Security Hye-Jung Park, Media Activist of permanent peace on the Korean Peninsula in South Korea and North Korea, women’s, Ann Wright, Retired US Army looms on the horizon, and Women Cross DMZ is peace, faith-based, humanitarian, and Korean Colonel, Diplomat Nan Kim, Associate Professor, University poised to play a key role in the process. diaspora organizations around the world to call of Wisconsin-Milwaukee for an end to the Korean War. We deepened our 2015 Delegation Members: How did we get here? partnerships with the South Korean women’s Gloria Steinem, Author and Activist peace movement, the Nobel Women’s Initiative, Janis Alton, Canadian Voice of Women for Peace The reversal began with the Winter Olympics, and Women’s International League for Peace Medea Benjamin, Code Pink when the two Koreas marched together carrying and Freedom and strengthened the U.S.-based Deann Borshay Liem, Filmmaker Hyun-Kyung Chung, Union the One Korea flag. -

12Th & Delaware

12th & Delaware DIRECTORS: Rachel Grady, Heidi Ewing U.S.A., 2009, 90 min., color On an unassuming corner in Fort Pierce, Florida, it’s easy to miss the insidious war that’s raging. But on each side of 12th and Delaware, soldiers stand locked in a passionate battle. On one side of the street sits an abortion clinic. On the other, a pro-life outfit often mistaken for the clinic it seeks to shut down. Using skillful cinema-vérité observation that allows us to draw our own conclusions, Rachel Grady and Heidi Ewing, the directors of Jesus Camp, expose the molten core of America’s most intractable conflict. As the pro-life volunteers paint a terrifying portrait of abortion to their clients, across the street, the staff members at the clinic fear for their doctors’ lives and fiercely protect the right of their clients to choose. Shot in the year when abortion provider Dr. George Tiller was murdered in his church, the film makes these FromFrom human rights to popular fears palpable. Meanwhile, women in need cuculture,lt these 16 films become pawns in a vicious ideological war coconfrontnf the subjects that with no end in sight.—CAROLINE LIBRESCO fi dedefine our time. Stylistic ExP: Sheila Nevins AsP: Christina Gonzalez, didiversityv and rigorous Craig Atkinson Ci: Katherine Patterson fifilmmakingl distinguish these Ed: Enat Sidi Mu: David Darling SuP: Sara Bernstein newnew American documentaries. Sunday, January 24, noon - 12DEL24TD Temple Theatre, Park City Wednesday, January 27, noon - 12DEL27YD Yarrow Hotel Theatre, Park City Wednesday, January 27, 9:00 p.m. - 12DEL27BN Broadway Centre Cinemas VI, SLC Thursday, January 28, 9:00 p.m. -

Speaker Bios

Women & War Book Launch and Symposium Power and Protection in the 21st Century May 5 and 6, 2011 Participant Bios Sanam Anderlini Executive Director/GNWP Adviser International Civil Society Action Network (ICAN) Sanam Naraghi-Anderlini is the co-founder of the International Civil society Action Network (ICAN) (www.icanpeacework.org), a US-based NGO dedicated to supporting civil society activism in peace and security in conflict affected countries. For over a decade she has been a leading international advocate, researcher, trainer and writer on conflict prevention and peacebuilding. In 2000 she was among civil society drafters of UN Security Council Resolution 1325 on women, peace and security. Between 2002 and 2005 as Director of the Women Waging Peace Policy Commission, Ms. Anderlini led ground breaking field research on women’s contributions to conflict prevention, security and peacemaking in 12 countries. Since 2005 she has also provided strategic guidance and training to key UN agencies, the UK government and NGOs worldwide, including leading a UNFPA/UNDP needs assessment into Maoist cantonment sites in Nepal. Between 2008 -2010 Ms. Anderlini was Lead Consultant for a 10-country UNDP global initiative on “Gender, Community Security and Social Cohesion" with a focus on men's experiences in crisis settings. She has served on the Advisory Board of the UN Democracy Fund (UNDEF), and was appointed to the Civil Society Advisory Group (CSAG) on Resolution 1325, chaired by Mary Robinson in 2010. She has written extensively on women and conflict issues including Women Building Peace: What they do, why it matters ( Rienner, 2007) and What the Women Say: Participation and SCR 1325 (MIT/ICAN 2010). -

Women & War Book Launch and Symposium

Women & War Book Launch and Symposium Power and Protection in the 21st Century May 5 and 6, 2011 Participant Bios Sanam Anderlini Executive Director/GNWP Adviser International Civil Society Action Network (ICAN) Sanam Naraghi-Anderlini is the co-founder of the International Civil society Action Network (ICAN) (www.icanpeacework.org), a US-based NGO dedicated to supporting civil society activism in peace and security in conflict affected countries. For over a decade she has been a leading international advocate, researcher, trainer and writer on conflict prevention and peacebuilding. In 2000 she was among civil society drafters of UN Security Council Resolution 1325 on women, peace and security. Between 2002 and 2005 as Director of the Women Waging Peace Policy Commission, Ms. Anderlini led ground breaking field research on women’s contributions to conflict prevention, security and peacemaking in 12 countries. Since 2005 she has also provided strategic guidance and training to key UN agencies, the UK government and NGOs worldwide, including leading a UNFPA/UNDP needs assessment into Maoist cantonment sites in Nepal. Between 2008 -2010 Ms. Anderlini was Lead Consultant for a UNDP global initiative on “Gender, Community Security and Social Cohesion" with a focus on men's experiences. She has served on the Advisory Board of the UN Democracy Fund (UNDEF), and in 2010 she was appointed to the Civil Society Advisory Group (CSAG) on Resolution 1325, chaired by Mary Robinson. In 2011 she will serve as the Senior Expert in Gender, Peace and Security Issues at the UN’s Mediation Support Unit Standby Team. Ms. Anderlini is a Senior Fellow at the MIT Center for International Studies. -

In Association with WNET Presents

in association with WNET presents A Film by Abigail E. Disney and Gini Reticker (USA, 2008, 72 minutes) www.PraytheDevilBacktoHell.com New York Press/Publicity Production Company Contact Fork Films Juli Kobayashi 25 E. 21st Street, 7th Floor, NY NY 10010 Operations Director [email protected] Fork Films (212) 782-3705 25 E. 21st Street, 7th Floor, NY NY 10010 [email protected] (212) 782-3706 TABLE OF CONTENTS SYNOPSIS.......................................................................................................................2 ABOUT THE FILM............................................................................................................2 ABOUT FORK FILMS ......................................................................................................3 DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT.............................................................................................4 PRODUCTION NOTES....................................................................................................4 A NOTE ON LIBERIA’S HISTORY...................................................................................6 FILMMAKER BIOGRAPHIES...........................................................................................7 CAST BIOGRAPHIES......................................................................................................9 WHAT CRITICS SAY ABOUT PRAY.............................................................................13 WHERE TO SEE PRAY THE DEVIL BACK TO HELL ..................................................14 -

Moderator & Panelists

WOMEN AS AGENTS OF CHANGE INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S DAY 3.8.2019 MODERATOR & PANELISTS VIRGINIA PRESCOTT MODERATOR RAZIA JAN Virginia Prescott is the Gracie Award-winning host of On Second Thought for Georgia Public Broadcasting. Before joining GPB, she was host of Word of Mouth, Writers on A New England Stage, and the iTunes Top Ten Podcasts Civics 101 and The 10-Minute Writers Workshop on New Hampshire Public Radio. Prior to joining NHPR, she was editor, producer, and director on NPR programs On Point and Here & Now, and Director of Interactive Media for New York Public Radio. Throughout her radio career, Virginia has worked to build sustainable indepen- dent radio in the developing world and has trained journalists in post-conflict zones from Sierra Leone to the Balkans. She was a member of the Peabody Award-winning production team for Jazz from Lincoln Center with Ed Bradley and the recipient of a Loeb Fellowship at Harvard University. Abigail E. Disney is a filmmaker, philanthropist, activist, and the Emmy-winning director of The Armor of Light. As President and CEO of the documentary production company Fork Films, she produced the groundbreaking Pray the Devil Back to Hell and co-created the subsequent ABIGAIL E. DISNEY PBS series Women, War & Peace. She is also the Chair and Co-Founder of Level Forward, a new ELVIA RAQUEC breed storytelling company focused on systemic change through creative excellence. The companies and stories that have most meaning for Abigail are the ones which foster human understanding. She has executive produced and supported over 100 projects through Fork Films’ funding program and created the nonprofit Peace is Loud, which uses storytelling to advance social movements, focusing on women’s rights and gender justice. -

Hasidic Women Upend Tradition by Forming an All-Female EMT Corps in ‘93QUEEN,’ Airing September 17, 2018 on POV

Contacts POV Communications 212-989-7425, [email protected] Adam Segal, Publicist [email protected] POV Pressroom pbs.org/pov/pressroom Hasidic Women Upend Tradition by Forming An All-Female EMT Corps in ‘93QUEEN,’ Airing September 17, 2018 on POV Paula Eiselt’s film portrays the challenges and eventual triumph of Hasidic Jewish women creating space for a new profession When Rachel “Ruchie” Freier introduces us to Borough Park, Brooklyn, one of the world’s largest enclaves of Hasidic Jews, she acknowledges the community’s prevailing view of a woman’s role: “The focus of a woman is being a mother. Any profession, or extra schooling, is discouraged.” In Paula Eiselt’s debut feature documentary, 93Queen, America’s first all-female EMT corps is born against this unlikely backdrop. 93Queen, directed by Paula Eiselt and produced by Eiselt and Heidi Reinberg, makes its national broadcast premiere on the PBS documentary series POV and pov.org on Monday, September 17 at 10 p.m. POV is American television’s longest-running documentary series now in its 31st season. The documentary is a co-production of American Documentary | POV and ITVS. As a practicing lawyer, Freier is already a member of the small subset of women in the community with professional degrees. She sees a need to rethink entrenched gender roles further when it comes to emergency services. Traditionally, all EMTs serving Brooklyn’s Hasidic neighborhoods come from the exclusively male volunteer organization Hatzolah. Although the rules against contact between unmarried men and women are waived during medical emergencies, Freier explains, “Most Hasidic women want a woman to help them.” Hence the name of the new EMT organization she begins building, Ezras Nashim (women who help). -

Contact: Melinda Kay Ronn [email protected] 917-743-7836

Contact: Melinda Kay Ronn [email protected] 917-743-7836 THE ARMOR OF LIGHT, A DOCUMENTARY BY ABIGAIL E. DISNEY AND FEATURING TDBI PRESIDENT, REV. ROB SCHENCK, HAS BEEN NOMINATED FOR AN EMMY AWARD Also Nominated for an Emmy, the PBS Town Hall, Armed in America: Faith and Guns, featuring TDBI President, Rev. Rob Schenck and other Evangelical Leaders (July 27, 2017 – Washington, D.C.) -- The Dietrich Bonhoeffer Institute is pleased to announce that the film, The Armor of Light, featuring TDBI President Reverend Rob Schenck, has been nominated for an Emmy for Outstanding Social Issue Documentary. In addition, the PBS Town Hall, Armed in America: Faith and Guns, featuring TDBI President, Rev. Rob Schenck and other Evangelical Christian leaders, has also been nominated for an Emmy for Outstanding News Special. The Armor of Light tracks Rev. Rob Schenck, pro-life activist and Evangelical conservative leader, who breaks with orthodoxy by questioning whether being pro-gun is consistent with being pro-life. Rev. Schenck is shocked and perplexed by the reactions of his long-time friends and colleagues who warn him away from this complex, politically explosive issue. Along the way, Rev. Schenck meets Lucy McBath, the mother of Jordan Davis, an unarmed teenager who was murdered in Florida and whose story has cast a spotlight on “Stand Your Ground” laws. Also an Evangelical Christian, McBath’s personal testimony compels Rev. Schenck to reach out to pastors around the country to discuss the moral and ethical response to gun violence. The Armor of Light follows these allies through their trials of conscience, heartbreak and rejection, as they bravely attempt to make others consider America’s gun culture through a moral lens.