The Agricultural Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 Farm Bill Primer: Support for Urban Agriculture

May 16, 2019 2018 Farm Bill Primer: Support for Urban Agriculture Over the past decade, food policy in the United States has (2) Urban Clusters of between 2,500 and 50,000 people responded to ongoing shifts in consumer preferences and (Figure 1). An urban area represents densely developed producer trends that favor local and regional food systems territory encompassing residential, commercial, and other while also supporting traditional farm enterprises. This nonresidential urban land uses. In contrast, rural areas support for local and regional farming has helped to encompass all population, housing, and territory not increase agricultural production in urban areas within and included within an urban area. Results from the most recent surrounding major U.S. cities. The 2018 farm bill 2010 U.S. Census indicate that the nation’s urban (Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018, P.L. 115-334) population increased by 12% from 2000 to 2010, outpacing provides additional support for urban, indoor, and other the nation’s overall growth of 10% for the same period. emerging agricultural production, creating new programs and authorities and providing additional funding for such Figure 1. Census Bureau Urban Designations, 2010 operations. The law also combines and expands existing programs administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to provide financial and resource management support for local and regional food production. Urban Farming Operations Urban farming operations represent a diverse range of systems and practices. They encompass large-scale innovative systems and capital-intensive operations, vertical and rooftop farms, hydroponic greenhouses (e.g., soilless systems), and aquaponic facilities (e.g., growing fish and plants together in an integrated system). -

Sample Costs for Beef Cattle, Cow-Calf Production

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AGRICULTURE AND NATURAL RESOURCES COOPERATIVE EXTENSION AGRICULTURAL ISSUES CENTER UC DAVIS DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURAL AND RESOURCE ECONOMICS SAMPLE COSTS FOR BEEF CATTLE COW – CALF PRODUCTION 300 Head NORTHERN SACRAMENTO VALLEY 2017 Larry C. Forero UC Cooperative Extension Farm Advisor, Shasta County. Roger Ingram UC Cooperative Extension Farm Advisor, Placer and Nevada Counties. Glenn A. Nader UC Cooperative Extension Farm Advisor, Sutter/Yuba/Butte Counties. Donald Stewart Staff Research Associate, UC Agricultural Issues Center and Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, UC Davis Daniel A. Sumner Director, UC Agricultural Issues Center, Costs and Returns Program, Professor, Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, UC Davis Beef Cattle Cow-Calf Operation Costs & Returns Study Sacramento Valley-2017 UCCE, UC-AIC, UCDAVIS-ARE 1 UC AGRICULTURE AND NATURAL RESOURCES COOPERATIVE EXTENSION AGRICULTURAL ISSUES CENTER UC DAVIS DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURAL AND RESOURCE ECONOMICS SAMPLE COSTS FOR BEEF CATTLE COW-CALF PRODUCTION 300 Head Northern Sacramento Valley – 2017 STUDY CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 2 ASSUMPTIONS 3 Production Operations 3 Table A. Operations Calendar 4 Revenue 5 Table B. Monthly Cattle Inventory 6 Cash Overhead 6 Non-Cash Overhead 7 REFERENCES 9 Table 1. COSTS AND RETURNS FOR BEEF COW-CALF PRODUCTION 10 Table 2. MONTHLY COSTS FOR BEEF COW-CALF PRODUCTION 11 Table 3. RANGING ANALYSIS FOR BEEF COW-CALF PRODUCTION 12 Table 4. EQUIPMENT, INVESTMENT AND BUSINESS OVERHEAD 13 INTRODUCTION The cattle industry in California has undergone dramatic changes in the last few decades. Ranchers have experienced increasing costs of production with a lack of corresponding increase in revenue. Issues such as international competition, and opportunities, new regulatory requirements, changing feed costs, changing consumer demand, economies of scale, and competing land uses all affect the economics of ranching. -

Permaculture Design Plan Alderleaf Farm

PERMACULTURE DESIGN PLAN FOR ALDERLEAF FARM Alderleaf Farm 18715 299th Ave SE Monroe, WA 98272 Prepared by: Alderleaf Wilderness College www.WildernessCollege.com 360-793-8709 [email protected] January 19, 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 What is Permaculture? 1 Vision for Alderleaf Farm 1 Site Description 2 History of the Alderleaf Property 3 Natural Features 4 SITE ELEMENTS: (Current Features, Future Plans, & Care) 5 Zone 0 5 Residences 5 Barn 6 Indoor Classroom & Office 6 Zone 1 7 Central Gardens & Chickens 7 Plaza Area 7 Greenhouses 8 Courtyard 8 Zone 2 9 Food Forest 9 Pasture 9 Rabbitry 10 Root Cellar 10 Zone 3 11 Farm Pond 11 Meadow & Native Food Forest 12 Small Amphibian Pond 13 Parking Area & Hedgerow 13 Well house 14 Zone 4 14 Forest Pond 14 Trail System & Tenting Sites 15 Outdoor Classroom 16 Flint-knapping Area 16 Zone 5 16 Primitive Camp 16 McCoy Creek 17 IMPLEMENTATION 17 CONCLUSION 18 RESOURCES 18 APPENDICES 19 List of Sensitive Natural Resources at Alderleaf 19 Invasive Species at Alderleaf 19 Master List of Species Found at Alderleaf 20 Maps 24 Frequently Asked Questions and Property Rules 26 Forest Stewardship Plan 29 Potential Future Micro-Businesses / Cottage Industries 29 Blank Pages for Input and Ideas 29 Introduction The permaculture plan for Alderleaf Farm is a guiding document that describes the vision of sustainability at Alderleaf. It describes the history, current features, future plans, care, implementation, and other key information that helps us understand and work together towards this vision of sustainable living. The plan provides clarity about each of the site elements, how they fit together, and what future plans exist. -

Guide to Raising Dairy Sheep

A3896-01 N G A N I M S I A L A I S R — Guide to raising N F O dairy sheep I O T C C Yves Berger, Claire Mikolayunas, and David Thomas U S D U O N P R O hile the United States has a long Before beginning a dairy sheep enterprise, history of producing sheep for producers should review the following Wmeat and wool, the dairy sheep fact sheet, designed to answer many of industry is relatively new to this country. the questions they will have, to determine In Wisconsin, dairy sheep flocks weren’t if raising dairy sheep is an appropriate Livestock team introduced until the late 1980s. This enterprise for their personal and farm industry remains a small but growing goals. segment of overall domestic sheep For more information contact: production: by 2009, the number of farms in North America reached 150, Dairy sheep breeds Claire Mikolayunas Just as there are cattle breeds that have with the majority located in Wisconsin, Dairy Sheep Initiative been selected for high milk production, the northeastern U.S., and southeastern Dairy Business Innovation Center there are sheep breeds tailored to Canada. Madison, WI commercial milk production: 608-332-2889 Consumers are showing a growing interest n East Friesian (Germany) [email protected] in sheep’s milk cheese. In 2007, the U.S. n Lacaune (France) David L. Thomas imported over 73 million pounds of sheep Professor of Animal Sciences milk cheese, such as Roquefort (France), n Sarda (Italy) Manchego (Spain), and Pecorino Romano University of Wisconsin-Madison n Chios (Greece) Madison, Wisconsin (Italy), which is almost twice the 37 million n British Milksheep (U.K.) 608-263-4306 pounds that was imported in 1985. -

Fiscal Policies for Sustainable Agriculture

Fiscal policies to support Policy Brief sustainable agriculture Agriculture and the SDGs highlight, agriculture subsidies often tend to disproportionately benefit large farmers/corporations and there are more effective ways of providing The agriculture and food production sector is central to the 2030 Agenda for support to people at risk of poverty and hunger. Sustainable Development. As the world’s largest employer, the sector can Addressing these pricing distortions and perverse incentives in the play an important role in efforts to reduce poverty, promote social equity agricultural sector will be critical for delivering several SDGs including and improve people’s livelihoods. However, unsustainable agricultural SDG2 (Zero Hunger), SDG12 (Responsible Production and Consumption), practices and associated land-use change have contributed to biodiversity SDG13 (Climate Action), SDG15 (Life on Land which includes targets on loss, water insecurity, climate change, soil and water pollution, threatening delivery of several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). For example, forestry and biodiversity). The SDG targets recognize the importance of studies have found that agriculture related land-use change is causing over correct food pricing to prevent trade restrictions and distortions in world 70 per cent of tropical deforestation1 and accounts for around one quarter agricultural markets, including the elimination of all forms of agricultural of all greenhouse gas emissions. Agriculture and food production can also export subsidies (T2.b). have significant impacts on human health and well-being. For example, pesticides are among the leading causes of death by self-poisoning, Role of fiscal policy reforms for particularly in low- and middle-income countries2, with related economic sustainable agriculture implications on health care costs and reduced productivity among others. -

Agricultural Policy and Its Impacts in Rural Economy in Nepal

Himalayan Journal of Development and Democracy, Vol. 6, No. 1, 2011 Agricultural Policy and its Impacts in Rural Economy in Nepal Rajendra Poudel 9 Division of Forestry & Natural Resources West Virginia University Introduction Nepal is considered a high population density developing country and a very high population density per unit of agriculture land. Comparative analysis with the region shows that the Bangladesh and Nepal have the lowest land to labor ratio (0.22 and 0.29 respectively), compared to India (0.61), Sri Lanka (0.51) and Pakistan (0.81). Small holding size of high land fragmentation in Nepal is one of the main reported causes of poverty in rural area. Nepal combines the status of least developed country, landlocked position between two giant protectionist countries (India and China), with attached castes system, armed conflict since 2002, very small farm size and high land fragmentation. The Agriculture Perspective Plan (1995- 2015) defined agriculture as the engine of growth with strong multiplier effects on employment and on other sectors of the economy. In 1995, the Agriculture Perspective Plan (APP) sets the objective of increasing average AGDP from 3% to 5%, and agricultural growth per capita to 3%. Statement of problem The agrarian and social structure of Nepal did not evolve quick enough to cope with the increasing demographic density over resources (contrary to India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Thailand). Participation for change is too late on several fronts (implementation of land reform, intensification techniques, mechanization, commercial alliance, production and trade groups, niche markets, quality control, minimum farm wage policy and monitoring etc.). -

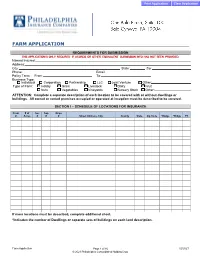

Farm Application

FARM APPLICATION REQUIREMENTS FOR SUBMISSION THIS APPLICATION IS ONLY REQUIRED IF ACORDS OR OTHER EQUIVALENT SUBMISSION INFO HAS NOT BEEN PROVIDED. Named Insured: Address: City: State: Zip: Phone: Email: Policy Term: From: To: Business Type: Individual Corporation Partnership LLC Joint Venture Other: Type of Farm: Hobby Grain Livestock Dairy Fruit Nuts Vegetables Vineyards Nursery Stock Other: ATTENTION: Complete a separate description of each location to be covered with or without dwellings or buildings. All owned or rented premises occupied or operated at inception must be described to be covered. SECTION I – SCHEDULE OF LOCATIONS FOR INSURANCE Prem # of Sec Twp Rnge # Acres # # # Street Address, City County State Zip Code *Dwlgs *Bldgs PC If more locations must be described, complete additional sheet. *Indicates the number of Dwellings or separate sets of buildings on each land description. Farm Application Page 1 of 16 02/2021 © 2021 Philadelphia Consolidated Holding Corp. SECTION II – ADDITIONAL INTEREST 1. Please check as applicable: Mortgagee Loss Payee Contract Holder Additional Insured Lessor of Leased Equipment 2. Name: Loan Number: 3. Address: City: State: Zip: 4. Applies to: 5. Please check as applicable: Mortgagee Loss Payee Contract Holder Additional Insured Lessor of Leased Equipment 6. Name: Loan Number: 7. Address: City: State: Zip: 8. Applies to: If additional lienholders needed, attach separate sheet. SECTION III – FARM LIABILITY COVERAGES LIMITS OF LIABILITY H. Bodily Injury & Property Damage $ I. Personal & Advertising Injury $ Basic Farm Liability Blanketed Acres Yes No Total Number of Acres Additional dwellings on insured farm location.owned by named insured or spouse Additional dwellings off insured farm location, owned by named insured or spouse and rented to others, but at least partly owner-occupied Additional dwellings off insured farm location, owned by named insured or spouse and rented to others with no part owner-occupied Additional dwellings on or off insured location, owned by a resident member of named insured’s household J. -

The Common Agricultural Policy: Separating Fact from Fiction

THE COMMON AGRICULTURAL POLICY SEPARATING FACT FROM FICTION 2 Agriculture and Rural Development The Common Agricultural Policy: Separating fact from fiction Contents 1. The cost of the common agricultural policy to the taxpayer is far too high. ..................... 2 2. Subsidies end up in the wrong hands: the EU spends money without control. ............... 2 3. Nobody knows who receives CAP funds. ....................................................................... 2 4. The EU supports mainly intensive farming. .................................................................... 3 5. There is no need to grant direct payments to EU farmers. Farmers should survive in the free market like any other business. ......................................................................... 3 6. The CAP does not do enough to help protect the environment. ...................................... 3 7. Farmers do not have any negotiating power in the food chain. The EU should do something about this. ..................................................................................................... 4 8. Europe should erect new import barriers to protect our farmers. .................................... 4 9. Overregulation is the cause of many farmers' problems and the EU is imposing too many rules on farmers. ................................................................................................... 4 10. The EU does not guarantee food quality. ....................................................................... 5 11. Farmers are getting -

Quantity of Livestock for Farm Deferral

Quantity of Livestock for Farm Deferral Factors Include: How many animals do you need to qualify for farm deferral? ▪ Soil Quality ▪ Use of Irrigation There is no simple answer to this question. Whether ▪ Time of Year you are trying to qualify for the farm deferral program ▪ Topography and Slope or simply remain in compliance, there are many ▪ Type and Size of Livestock underlying factors. ▪ Wooded Vs. Open Each property is unique in how many animals per acre it can support. The following general guidelines have been developed. This is a suggested number of animals, because it varies on weight, size, breed and sex of animal. Approximate Requirements for Adult Animals on Dry Pasture: This is a rough estimate of how many pounds per acre. Horses (Excluding personal/pleasure) 1 head per 2 acres Typically, 100-800 Cattle – 1 to 2 head per 2 acres pounds minimum on Llamas – 1 to 2 head per acre dry and 500-1000 on irrigated pasture. Sheep – 2 to 4 head per acre Goats – 3 to 5 head per acre Range Chickens – 100-300 per acre size Important to Remember: The portion of the property in farm deferral must be used fully and exclusively for a compliant farming practice with the primary intent of making a profit. It must contain quality forage and be free of invasive weeds and brush. The forage must be grazed by sufficient number of livestock to keep it eaten down during the growing season. If pasture has adequate livestock but is full of blackberry briars, noxious weeds like scotch broom and tansy ragwort, or is full of debris like scrap metal, it will NOT qualify for farm use. -

Diversifying Cropping Systems PROFILE: THEY DIVERSIFIED to SURVIVE 3

Opportunities in Agriculture CONTENTS WHY DIVERSIFY? 2 Diversifying Cropping Systems PROFILE: THEY DIVERSIFIED TO SURVIVE 3 ALTERNATIVE CROPS 4 PROFILE: DIVERSIFIED NORTH DAKOTAN WORKS WITH MOTHER NATURE 9 PROTECT NATURAL RESOURCES, RENEW PROFITS 10 AGROFORESTRY 13 PROFILE: PROFITABLE PECANS WORTH THE WAIT 15 STRENGTHEN COMMUNITY, SHARE LABOR 15 PROFILE: STRENGTHENING TIES AMONG MAINE FARMERS 16 RESOURCES 18 Alternative grains and oilseeds – like, from left, buckwheat, amaranth and flax – add diversity to cropping systems and open profitable niche markets while contributing to environmentally sound operations. – Photos by Rob Myers Published by the Sustainable KARL KUPERS, AN EASTERN WASHINGTON GRAIN GROWER, Although growing alternative crops to diversify a Agriculture Network (SAN), was a typical dryland wheat farmer who idled his traditional farm rotation increase profits while lessen- the national outreach arm land in fallow to conserve moisture. After years of ing adverse environmental impacts, the majority of of the Sustainable Agriculture watching his soil blow away and his market price slip, U.S. cropland is still planted in just three crops: soy- Research and Education he made drastic changes to his 5,600-acre operation. beans, corn and wheat. That lack of crop diversity (SARE) program, with funding In place of fallow, he planted more profitable hard can cause problems for farmers, from low profits by USDA's Cooperative State red and hard white wheats along with seed crops like to soil erosion. Adding new crops that fit climate, Research, Education and condiment mustard, sunflower, grass and safflower. geography and management preferences can Extension Service. All of those were drilled using a no-till system Kupers improve not only your bottom line, but also your calls direct-seeding. -

What Was the Effect of New Crops in the Agricultural Revolution? Evidence from an Arbitrage Model of Crop Rotation

What was the Effect of New Crops in the Agricultural Revolution? Evidence from an Arbitrage Model of Crop Rotation Liam Brunt1 Abstract In this paper we develop an arbitrage model of crop rotation that enables us to estimate the impact of crop rotation on wheat yields, using only the yields and prices of each crop employed in the rotation. We apply this technique to eighteenth century England to assess the importance of two new crops – turnips and clover – in raising wheat yields. Contrary to the received wisdom, we show that turnips substantially pushed up wheat yields but clover pushed down wheat yields. We confirm this result by comparing our estimates to both experimental data and production function estimates. Further detailed analysis facilitated by the new model enables us to explain this surprising result in terms of the management practices pursued by farmers. Keywords: agriculture, crop rotation, technological change. JEL Classification: N01, N53, O13, Q12. 1 I would like to thank James Foreman-Peck and Lucy White for helpful comments. Any remaining errors are my own responsibility. An arbitrage model of crop rotation 2 I. Introduction. The defining feature of the Industrial Revolution in England was the transfer of labour resources from agriculture to industry, which occurred exceptionally early by international standards.2 But England had to remain virtually self-sufficient in food production during the eighteenth century because very few exportable surpluses were being generated by other European countries.3 The adoption of new technology was a crucial factor that permitted England to attain a high level of agricultural labour productivity – which in turn facilitated labour release.4 The number and range of innovations coming into general use in the eighteenth century has prompted commentators to dub it the period of the ‘Agricultural Revolution’.5 There were new animal breeds (the Shire horse and the dairy short horn cow); new crops (turnips and clover); new machines (seed drills and threshers); and new hand tools (the cradle scythe). -

Strengthening Farm-Agribusiness Linkages in Africa Iii

$*6) 2FFDVLRQDO 3DSHU 6WUHQJWKHQLQJ IDUPDJULEXVLQHVV OLQNDJHVLQ$IULFD 6XPPDU\UHVXOWVRIILYH FRXQWU\VWXGLHVLQ*KDQD 1LJHULD.HQ\D8JDQGDDQG 6RXWK$IULFD $*6) 2FFDVLRQDO 3DSHU 6WUHQJWKHQLQJ IDUPDJULEXVLQHVV OLQNDJHVLQ$IULFD 6XPPDU\UHVXOWVRIILYH FRXQWU\VWXGLHVLQ*KDQD 1LJHULD.HQ\D8JDQGDDQG 6RXWK$IULFD E\ $QJHOD'DQQVRQ$FFUD*KDQD &KXPD(]HGLQPD,EDGDQ1LJHULD 7RP5HXEHQ:DPEXD1MXUX.HQ\D %HUQDUG%DVKDVKD0DNHUHUH8QLYHUVLW\8JDQGD -RKDQQ.LUVWHQDQG.XUW6DWRULXV3UHWRULD6RXWK$IULFD (GLWHGE\$OH[DQGUD5RWWJHU $JULFXOWXUDO0DQDJHPHQW0DUNHWLQJDQG)LQDQFH6HUYLFH $*6) $JULFXOWXUDO6XSSRUW6\VWHPV'LYLVLRQ )22'$1'$*5,&8/785(25*$1,=$7,212)7+(81,7('1$7,216 5RPH 5IFEFTJHOBUJPOTFNQMPZFEBOEUIFQSFTFOUBUJPOPGNBUFSJBM JOUIJTJOGPSNBUJPOQSPEVDUEPOPUJNQMZUIFFYQSFTTJPOPGBOZ PQJOJPOXIBUTPFWFSPOUIFQBSUPGUIF'PPEBOE"HSJDVMUVSF 0SHBOJ[BUJPO PG UIF 6OJUFE /BUJPOT DPODFSOJOH UIF MFHBM PS EFWFMPQNFOUTUBUVTPGBOZDPVOUSZ UFSSJUPSZ DJUZPSBSFBPSPG JUTBVUIPSJUJFT PSDPODFSOJOHUIFEFMJNJUBUJPOPGJUTGSPOUJFSTPS CPVOEBSJFT "MM SJHIUT SFTFSWFE 3FQSPEVDUJPO BOE EJTTFNJOBUJPO PG NBUFSJBM JO UIJT JOGPSNBUJPOQSPEVDUGPSFEVDBUJPOBMPSPUIFSOPODPNNFSDJBMQVSQPTFTBSF BVUIPSJ[FEXJUIPVUBOZQSJPSXSJUUFOQFSNJTTJPOGSPNUIFDPQZSJHIUIPMEFST QSPWJEFEUIFTPVSDFJTGVMMZBDLOPXMFEHFE3FQSPEVDUJPOPGNBUFSJBMJOUIJT JOGPSNBUJPOQSPEVDUGPSSFTBMFPSPUIFSDPNNFSDJBMQVSQPTFTJTQSPIJCJUFE XJUIPVUXSJUUFOQFSNJTTJPOPGUIFDPQZSJHIUIPMEFST"QQMJDBUJPOTGPSTVDI QFSNJTTJPOTIPVMECFBEESFTTFEUPUIF$IJFG 1VCMJTIJOH.BOBHFNFOU4FSWJDF *OGPSNBUJPO%JWJTJPO '"0 7JBMFEFMMF5FSNFEJ$BSBDBMMB 3PNF *UBMZ PSCZFNBJMUPDPQZSJHIU!GBPPSH ª'"0 Strengthening farm-agribusiness