Castilleja in the Garden, DAVE NELSON and DAVID JOYNER 279

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plant Physiology

PLANT PHYSIOLOGY Vince Ördög Created by XMLmind XSL-FO Converter. PLANT PHYSIOLOGY Vince Ördög Publication date 2011 Created by XMLmind XSL-FO Converter. Table of Contents Cover .................................................................................................................................................. v 1. Preface ............................................................................................................................................ 1 2. Water and nutrients in plant ............................................................................................................ 2 1. Water balance of plant .......................................................................................................... 2 1.1. Water potential ......................................................................................................... 3 1.2. Absorption by roots .................................................................................................. 6 1.3. Transport through the xylem .................................................................................... 8 1.4. Transpiration ............................................................................................................. 9 1.5. Plant water status .................................................................................................... 11 1.6. Influence of extreme water supply .......................................................................... 12 2. Nutrient supply of plant ..................................................................................................... -

Summer 2012 RURAL LIVING& in ARIZONA Volume 6, Number 2

Backyards Beyond Summer 2012 RURAL LIVING& IN ARIZONA Volume 6, Number 2 Summer 2012 1 Common Name: Wholeleaf Indian paintbrush A spike of showy, reddish-orange like projections of parasitic tissue called Scientific Name: Castilleja integra bracts generally calls our attention to haustoria, which grow from the roots of the this paintbrush. The showy color of the paintbrush and penetrate the roots of the host paintbrush plant is produced by the bracts plant. They do not completely deplete the (modified leaves) that occur in a variety nutrients from the host plant, although it often of colors. The greenish, tinged scarlet, does take a toll on its fitness and growth. tubular true flowers are inconspicuously Castilleja species are generalist parasites - hidden among the bracts. "Integra", Latin they do not require a particular host species; for "whole", refers to the bracts and leaves however, you will often find paintbrush which are not incised or lobed as in many growing together with bunchgrass, chamise, other species of Castilleja. Castilleja integra sagebrush, lupine and wild buckwheat. is a perennial and is one of about 200 The flowers of Indian paintbrush are species of the genus Castilleja in the family edible and sweet, but must be eaten in small of Scrophulariaceae (Figwort or Snapdragon quantities. These plants have a tendency Family). It grows to a maximum of about to absorb and concentrate selenium in their twenty inches tall. The plant ranges through tissues from the soils in which they grow, the southwest in Pinyon/Juniper and and can be potentially very toxic if the roots Ponderosa forest communities at elevations Sue Smith or green parts of the plant are consumed. -

Guide to the Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- LILIACEAE

Guide to the Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- LILIACEAE LILIACEAE de Jussieu 1789 (Lily Family) (also see AGAVACEAE, ALLIACEAE, ALSTROEMERIACEAE, AMARYLLIDACEAE, ASPARAGACEAE, COLCHICACEAE, HEMEROCALLIDACEAE, HOSTACEAE, HYACINTHACEAE, HYPOXIDACEAE, MELANTHIACEAE, NARTHECIACEAE, RUSCACEAE, SMILACACEAE, THEMIDACEAE, TOFIELDIACEAE) As here interpreted narrowly, the Liliaceae constitutes about 11 genera and 550 species, of the Northern Hemisphere. There has been much recent investigation and re-interpretation of evidence regarding the upper-level taxonomy of the Liliales, with strong suggestions that the broad Liliaceae recognized by Cronquist (1981) is artificial and polyphyletic. Cronquist (1993) himself concurs, at least to a degree: "we still await a comprehensive reorganization of the lilies into several families more comparable to other recognized families of angiosperms." Dahlgren & Clifford (1982) and Dahlgren, Clifford, & Yeo (1985) synthesized an early phase in the modern revolution of monocot taxonomy. Since then, additional research, especially molecular (Duvall et al. 1993, Chase et al. 1993, Bogler & Simpson 1995, and many others), has strongly validated the general lines (and many details) of Dahlgren's arrangement. The most recent synthesis (Kubitzki 1998a) is followed as the basis for familial and generic taxonomy of the lilies and their relatives (see summary below). References: Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (1998, 2003); Tamura in Kubitzki (1998a). Our “liliaceous” genera (members of orders placed in the Lilianae) are therefore divided as shown below, largely following Kubitzki (1998a) and some more recent molecular analyses. ALISMATALES TOFIELDIACEAE: Pleea, Tofieldia. LILIALES ALSTROEMERIACEAE: Alstroemeria COLCHICACEAE: Colchicum, Uvularia. LILIACEAE: Clintonia, Erythronium, Lilium, Medeola, Prosartes, Streptopus, Tricyrtis, Tulipa. MELANTHIACEAE: Amianthium, Anticlea, Chamaelirium, Helonias, Melanthium, Schoenocaulon, Stenanthium, Veratrum, Toxicoscordion, Trillium, Xerophyllum, Zigadenus. -

The Ustilaginales (Smut Fungi) of Ohio*

THE USTILAGINALES (SMUT FUNGI) OF OHIO* C. W. ELLETT Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, The Ohio State University, Columbus 10 The smut fungi are in the order Ustilaginales with one family, the Ustilaginaceae, recognized. They are all plant parasites. In recent monographs 276 species in 22 genera are reported in North America and more than 1000 species have been reported from the world (Fischer, 1953; Zundel, 1953; Fischer and Holton, 1957). More than one half of the known smut fungi are pathogens of species in the Gramineae. Most of the smut fungi are recognized by the black or brown spore masses or sori forming in the inflorescences, the leaves, or the stems of their hosts. The sori may involve the entire inflorescence as Ustilago nuda on Hordeum vulgare (fig. 2) and U. residua on Danthonia spicata (fig. 7). Tilletia foetida, the cause of bunt of wheat in Ohio, sporulates in the ovularies only and Ustilago violacea which has been found in Ohio on Silene sp. forms spores only in the anthers of its host. The sori of Schizonella melanogramma on Carex (fig. 5) and of Urocystis anemones on Hepatica (fig. 4) are found in leaves. Ustilago striiformis (fig. 6) which causes stripe smut of many grasses has sori which are mostly in the leaves. Ustilago parlatorei, found in Ohio on Rumex (fig. 3), forms sori in stems, and in petioles and midveins of the leaves. In a few smut fungi the spore masses are not conspicuous but remain buried in the host tissues. Most of the species in the genera Entyloma and Doassansia are of this type. -

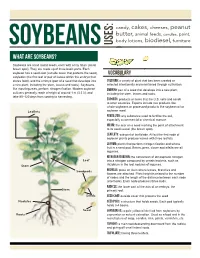

What Are Soybeans?

candy, cakes, cheeses, peanut butter, animal feeds, candles, paint, body lotions, biodiesel, furniture soybeans USES: What are soybeans? Soybeans are small round seeds, each with a tiny hilum (small brown spot). They are made up of three basic parts. Each soybean has a seed coat (outside cover that protects the seed), VOCABULARY cotyledon (the first leaf or pair of leaves within the embryo that stores food), and the embryo (part of a seed that develops into Cultivar: a variety of plant that has been created or a new plant, including the stem, leaves and roots). Soybeans, selected intentionally and maintained through cultivation. like most legumes, perform nitrogen fixation. Modern soybean Embryo: part of a seed that develops into a new plant, cultivars generally reach a height of around 1 m (3.3 ft), and including the stem, leaves and roots. take 80–120 days from sowing to harvesting. Exports: products or items that the U.S. sells and sends to other countries. Exports include raw products like whole soybeans or processed products like soybean oil or Leaflets soybean meal. Fertilizer: any substance used to fertilize the soil, especially a commercial or chemical manure. Hilum: the scar on a seed marking the point of attachment to its seed vessel (the brown spot). Leaflets: sub-part of leaf blade. All but the first node of soybean plants produce leaves with three leaflets. Legume: plants that perform nitrogen fixation and whose fruit is a seed pod. Beans, peas, clover and alfalfa are all legumes. Nitrogen Fixation: the conversion of atmospheric nitrogen Leaf into a nitrogen compound by certain bacteria, such as Stem rhizobium in the root nodules of legumes. -

Alternative Strategies for Clonal Plant Reproduction©

Alternative Strategies for Clonal Plant Reproduction 269 Alternative Strategies for Clonal Plant Reproduction© Robert L. Geneve University of Kentucky, Department of Horticulture, Lexington, Kentucky 40546 U.S.A. Email: [email protected] INTRODUCTION Pick up any biology textbook and there will be a description of the typical sexual life cycle for plants. In higher plants, the life cycle starts with seed germination followed by vegetative growth leading to flower and gamete formation with the ultimate goal of creating genetically diverse offspring through seed production. The fern life cycle is more primitive but follows a similar progression from spore germi- nation to the gametophytic generation leading to sexual union of gametes resulting in the leafy sporophyte, which in turn creates the spores. Interestingly, plants have evolved unique alternative life cycles that bypass typi- cal seed production in favor of clonal reproduction systems. This may seem counter- intuitive because sexual reproduction should lead to greater genetic diversity in offspring compared to clonal plants. These sexual offspring should have a higher potential to adapt to new or changing environments, i.e., be more successful. How- ever, investing in clonal reproduction seems to increase the likelihood that a species can colonize specific environmental niches. It has been observed that many of the perennial species in a given ecosystem tend to combine both sexual and clonal forms of reproduction (Ellstrand and Roose, 1987). Additionally, unique clonal propaga- tion systems tend to be more prevalent in plants adapted to extreme environments like arctic, xerophytic, and Mediterranean climates. Mini-Review Objectives. The objective of this mini-review is to describe some of the ways plants have evolved clonal reproduction strategies that allow unique plants to colonize extreme environments. -

Minnesota Biodiversity Atlas Plant List

Cannon River Trout Lily SNA Plant List Herbarium Scientific Name Minnesota DNR Common Name Status Acer negundo box elder Acer saccharum sugar maple Achillea millefolium common yarrow Adiantum pedatum maidenhair fern Agastache scrophulariaefolia purple giant hyssop Ageratina altissima white snakeroot Agrostis stolonifera spreading bentgrass Allium tricoccum tricoccum wild leek Ambrosia artemisiifolia common ragweed Ambrosia trifida great ragweed Anemone acutiloba sharp-lobed hepatica Anemone quinquefolia quinquefolia wood anemone Anemone virginiana alba tall thimbleweed Antennaria parlinii fallax Parlin's pussytoes Aquilegia canadensis columbine Arctium minus common burdock Arisaema triphyllum Jack-in-the-pulpit Asarum canadense wild ginger Asclepias speciosa showy milkweed Athyrium filix-femina angustum lady fern Barbarea vulgaris yellow rocket Bromus inermis smooth brome Campanula americana tall bellflower Capsella bursa-pastoris shepherd's-purse Cardamine concatenata cut-leaved toothwort Carex cephalophora oval-headed sedge Carex gravida heavy sedge Carex grisea ambiguous sedge Carex rosea starry sedge Carex sprengelii Sprengel's sedge Carex vulpinoidea fox sedge Carya cordiformis bitternut hickory Caulophyllum thalictroides blue cohosh Celtis occidentalis hackberry Cerastium fontanum mouse-ear chickweed Chenopodium album white lamb's quarters Circaea lutetiana canadensis common enchanter's nightshade Cirsium discolor field thistle Cirsium vulgare bull thistle Claytonia virginica Virginia spring beauty Conyza canadensis horseweed © -

Castilleja Coccinea and C. Indivisa (Orobanchaceae)

Nesom, G.L. and J.M. Egger. 2014. Castilleja coccinea and C. indivisa (Orobanchaceae). Phytoneuron 2014-14: 1–7. Published 6 January 2014. ISSN 2153 733X CASTILLEJA COCCINEA AND C. INDIVISA (OROBANCHACEAE) GUY L. NESOM 2925 Hartwood Drive Fort Worth, Texas 76109 www.guynesom.com J. M ARK EGGER Herbarium, Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture University of Washington Seattle, Washington 98195-5325 [email protected] ABSTRACT Castilleja coccinea and C. indivisa are contrasted in morphology and their ranges mapped in detail in the southern USA, where they are natively sympatric in small areas of Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Louisiana. Castilleja indivisa has recently been introduced and naturalized in the floras of Alabama and Florida. Castilleja ludoviciana , known only by the type collection from southwestern Louisiana, differs from C. coccinea in subentire leaves and relatively small flowers and is perhaps a population introgressed by C. indivisa . Castilleja coccinea and C. indivisa are allopatric except in small areas of Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Lousiana, but assessments of their native distributions are not consistent among various accounts (e.g. Thomas & Allen 1997; Turner et al. 2003; OVPD 2012; USDA, NRCS 2013). Morphological contrasts between the two species, via keys in floristic treatments (e.g., Smith 1994; Wunderlin & Hansen 2003; Nelson 2009; Weakley 2012), have essentially repeated the differences outlined by Pennell (1935). The current study presents an evaluation and summary of the taxonomy of these two species. We have examined specimens at CAS, TEX-LL, SMU-BRIT-VDB, MO, NLU, NO, USF, WS, and WTU and viewed digital images available through Florida herbaria and databases. -

Conserving Europe's Threatened Plants

Conserving Europe’s threatened plants Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation Conserving Europe’s threatened plants Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation By Suzanne Sharrock and Meirion Jones May 2009 Recommended citation: Sharrock, S. and Jones, M., 2009. Conserving Europe’s threatened plants: Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation Botanic Gardens Conservation International, Richmond, UK ISBN 978-1-905164-30-1 Published by Botanic Gardens Conservation International Descanso House, 199 Kew Road, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 3BW, UK Design: John Morgan, [email protected] Acknowledgements The work of establishing a consolidated list of threatened Photo credits European plants was first initiated by Hugh Synge who developed the original database on which this report is based. All images are credited to BGCI with the exceptions of: We are most grateful to Hugh for providing this database to page 5, Nikos Krigas; page 8. Christophe Libert; page 10, BGCI and advising on further development of the list. The Pawel Kos; page 12 (upper), Nikos Krigas; page 14: James exacting task of inputting data from national Red Lists was Hitchmough; page 16 (lower), Jože Bavcon; page 17 (upper), carried out by Chris Cockel and without his dedicated work, the Nkos Krigas; page 20 (upper), Anca Sarbu; page 21, Nikos list would not have been completed. Thank you for your efforts Krigas; page 22 (upper) Simon Williams; page 22 (lower), RBG Chris. We are grateful to all the members of the European Kew; page 23 (upper), Jo Packet; page 23 (lower), Sandrine Botanic Gardens Consortium and other colleagues from Europe Godefroid; page 24 (upper) Jože Bavcon; page 24 (lower), Frank who provided essential advice, guidance and supplementary Scumacher; page 25 (upper) Michael Burkart; page 25, (lower) information on the species included in the database. -

Molecular Investigation of the Origin of Castilleja Crista-Galli by Sarah

Molecular investigation of the origin of Castilleja crista-galli by Sarah Youngberg Mathews A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Biological Sciences Montana State University © Copyright by Sarah Youngberg Mathews (1990) Abstract: An hypothesis of hybrid origin of Castilleja crista-galli (Scrophulariaceae) was studied. Hybridization and polyploidy are widespread in Castilleja and are often invoked as a cause of difficulty in defining species and as a speciation model. The putative allopolyploid origin of Castilleja crista-gralli from Castilleja miniata and Castilleja linariifolia was investigated using molecular, morphological and cytological techniques. Restriction site analysis of chloroplast DNA revealed high homogeneity among the chloroplast genomes of species of Castilleja and two Orthocarpus. No species of Castilleia represented by more than one population in the analysis was characterized by a distinctive choroplast genome. Genetic distances estimated from restriction site mutations between any two species or between genera are comparable to distances reported from other plant groups, but both intraspecific and intrapopulational distances are high relative to other groups. Restriction site analysis of nuclear ribosomal DNA revealed variable repeat types both within and among individuals. Qualitative species groupings based on restriction site mutations in the ribosomal DNA repeat units do not place Castilleja crista-galli with either putative parent in a consistent manner. A cladistic analysis of 11 taxa using 10 morphological characters places Castilleja crista-galli in an unresolved polytomy with both putative parents and Castilleja hispida. Cytological analyses indicate that Castilleja crista-gralli is not of simple allopolyploid origin. Both diploid and tetraploid chromosome counts are reported for this species, previously known only as an octoploid. -

Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Fort Bowie National Historic Site Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Fort Bowie National Historic Site

Powell, Schmidt, Halvorson In Cooperation with the University of Arizona, School of Natural Resources Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Fort Bowie National Historic Site Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Fort Bowie National Historic Site Plant and Vertebrate Vascular U.S. Geological Survey Southwest Biological Science Center 2255 N. Gemini Drive Flagstaff, AZ 86001 Open-File Report 2005-1167 Southwest Biological Science Center Open-File Report 2005-1167 February 2007 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey National Park Service In cooperation with the University of Arizona, School of Natural Resources Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Fort Bowie National Historic Site By Brian F. Powell, Cecilia A. Schmidt , and William L. Halvorson Open-File Report 2005-1167 December 2006 USGS Southwest Biological Science Center Sonoran Desert Research Station University of Arizona U.S. Department of the Interior School of Natural Resources U.S. Geological Survey 125 Biological Sciences East National Park Service Tucson, Arizona 85721 U.S. Department of the Interior DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Mark Myers, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2006 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS-the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web:http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Suggested Citation Powell, B. F, C. A. Schmidt, and W. L. Halvorson. 2006. Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Fort Bowie National Historic Site. -

The Evolution of Pollinator–Plant Interaction Types in the Araceae

BRIEF COMMUNICATION doi:10.1111/evo.12318 THE EVOLUTION OF POLLINATOR–PLANT INTERACTION TYPES IN THE ARACEAE Marion Chartier,1,2 Marc Gibernau,3 and Susanne S. Renner4 1Department of Structural and Functional Botany, University of Vienna, 1030 Vienna, Austria 2E-mail: [email protected] 3Centre National de Recherche Scientifique, Ecologie des Foretsˆ de Guyane, 97379 Kourou, France 4Department of Biology, University of Munich, 80638 Munich, Germany Received August 6, 2013 Accepted November 17, 2013 Most plant–pollinator interactions are mutualistic, involving rewards provided by flowers or inflorescences to pollinators. An- tagonistic plant–pollinator interactions, in which flowers offer no rewards, are rare and concentrated in a few families including Araceae. In the latter, they involve trapping of pollinators, which are released loaded with pollen but unrewarded. To understand the evolution of such systems, we compiled data on the pollinators and types of interactions, and coded 21 characters, including interaction type, pollinator order, and 19 floral traits. A phylogenetic framework comes from a matrix of plastid and new nuclear DNA sequences for 135 species from 119 genera (5342 nucleotides). The ancestral pollination interaction in Araceae was recon- structed as probably rewarding albeit with low confidence because information is available for only 56 of the 120–130 genera. Bayesian stochastic trait mapping showed that spadix zonation, presence of an appendix, and flower sexuality were correlated with pollination interaction type. In the Araceae, having unisexual flowers appears to have provided the morphological precon- dition for the evolution of traps. Compared with the frequency of shifts between deceptive and rewarding pollination systems in orchids, our results indicate less lability in the Araceae, probably because of morphologically and sexually more specialized inflorescences.