The Sign of Peace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Offertory Our Firstfruits the Offertory

God. For in a sense when we offer our gifts at the Altar, we are actually offering ourselves. Our money is a part of ourselves, what we have earned, what we have la- bored for. And thus the offering of our possessions be- comes the offering of our very beings. But if we think of our offering in the Service as a sacrifice of ourselves, then we will also want to carry out this sacrifice in our daily lives—otherwise the offering of our possessions would be only hypocrisy. Furthermore, when we offer at the Altar, we are offer- ing in union with our Lord Jesus Christ—offering our imperfect sacrifices in union with the perfect Sacrifice of His Body and Blood, which He offered to His heavenly Father. For it is only because of His perfect Sacrifice that our sacrifices are of any value. The Offertory Our Firstfruits The Offertory Finally, our offering is to be the firstfruits of our la- bor—not what happens to be left over after all of our bills and debts have been paid. But our offering at the Altar ought to be a sacrifice of the first and the best we can give. If we Christians would consider our offerings in this way—as a fulfillment of our Royal Priesthood, a privi- lege, and a sacrifice of our firstfruits, then we would more readily offer ourselves, our bodies, and souls and I N C A R N A T E W O R D T R A C T S E R I E S all things as a living sacrifice, holy, acceptable to God - 2 4 - through Jesus Christ our Lord. -

1 Brief on Eur/Nat States Restrictions Due to Covid-19

BRIEF ON EUR/NAT STATES RESTRICTIONS DUE TO COVID-19 (Monday, 28 September 2020) Disclaimer Total:The purpose 26 NOTAMs of this Brief is for information. All operational stakeholders are requested to consult the most up-to-date AIS publications. The sources of this Brief are the NOTAM Summary published on EUROCONTROL Network Operations Portal, the ICAO ISTARS Portal (NOTAMs issued by States explicitly including COVID-19 related information) and IATA travel centre (COVID-19) website. Country Status / Restriction Albania No flight suspensions to Albania Please check immigration restriction. Algeria Flights to Algeria are suspended except State, cargo, medevac, technical landings where crews and passengers do not disembark, private purpose flights and repatriation flights; all with permission from the Algerian CAA Andorra Apply the relevant Coronavirus (COVID-19) regulations of France or Spain, whichever must be transited to enter Andorra. Armenia Pax restrictions and entry conditions due to the State of Emergency declared by the Armenian Government as a result of the epidemic situation caused by the spread of Covid-19 Austria Pax restrictions with exemptions granted Aircraft operators are obliged to collect contact details of pax if coming from the affected countries are listed; https://www.bmeia.gv.at/reise-aufenthalt/reisewarnungen LOWS, LOWK availability Azerbaijan All international pax flights to/from Azerbaijan are restricted with exemptions granted Resumption of international pax flights only after agreement of Government of Azerbaijan taking into account epidemiology situation and other restrictions Pax restrictions, entry conditions Belarus A completed awareness questionnaire must be presented upon arrival, this does not apply to passengers in transit. -

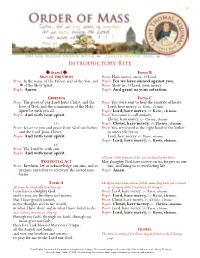

Stand Priest: in the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy

1 Stand Form B SIGN OF THE CROSS Priest: Have mercy on us, O Lord. Priest: In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and People: For we have sinned against you. ✠of the Holy Spirit. Priest: Show us, O Lord, your mercy. People: Amen. People: And grant us your salvation. GREETING Form C Priest: The grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, and the Priest: You were sent to heal the contrite of heart: love of God, and the communion of the Holy Lord, have mercy. Or: Kyrie, eleison. Spirit be with you all. People: Lord, have mercy. Or: Kyrie, eleison. People: And with your spirit. Priest: You came to call sinners: Christ, have mercy. Or: Christe, eleison. Or: People: Christ, have mercy. Or: Christe, eleison. Priest: Grace to you and peace from God our Father Priest: You are seated at the right hand of the Father and the Lord Jesus Christ. to intercede for us: People: And with your spirit. Lord, have mercy. Or: Kyrie, eleison. People: Lord, have mercy. Or: Kyrie, eleison. Or: Priest: The Lord be with you. People: And with your spirit. All forms of the Penitential Act are concluded by the Priest: PENITENTIAL ACT May almighty God have mercy on us, forgive us our Priest: Brethren, let us acknowledge our sins, and so sins, and bring us to everlasting life. prepare ourselves to celebrate the sacred mys- People: Amen. teries. Form A The Kyrie eleison invocations follow, unless they have just occurred All pause for silent reflection then say: in a formula of the Penitential Act (Form C). -

Sacristan Pamphlet January 2021

Orientation and Training For more information, please contact: The orientation and training of an Sacristan aspiring sacristan is designed to Dave and Kathy Martz remove any uncertainty or concern 303-683-9524 Ministry and to encourage and support [email protected] participation in the Pax Christi [email protected] Sacristan Ministry. The orientation is brief. It provides an over-view of the routine sacristan duties and identifies the resources available to the sacristan in support of his/her ministry. The training is about a two hour practicum on the routine procedures for unlocking the Church, setting up for Mass and securing the Sanctuary/Church following Mass. The Pax Christi Sacristan Handbook provides guidance for the routine sacristan duties for weekend celebrations and most special occasions. The Sacristan Handbook, available in the Sacristy, is a great check list for confirming that all is Pax Christi Catholic Church ready for the celebration of the 5761 McArthur Ranch Road Mass. The Pax Christi Sacristan Littleton, CO 80124 Handbook also becomes the 303-799-1036 property of each sacristan. www.paxchristi.org The Joy of Being a Sacristan The Mission and Duties of the Sacristan Please pray about joining the Pax Simply stated, the mission of the Sacristan Ministry is to be the guardian of the Christi Sacristan Ministry. Sacristans Church, prepare the Church for Mass, assist the Celebrant and other liturgical play an important and spiritually ministers, and be of service to the church assembly. rewarding behind-the-scenes role in our liturgy. They arrive early to prepare The prerequisites for being a sacristan: the Church for Mass and assist the • One must be a confirmed and practicing Catholic, and registered parishioner Celebrant and other liturgical liturgists, • One must be approved by the Pastor or Parochial Administrator as needed. -

“Paul, a Plan, & an Epistle”

Weekly Events THE LORD’S DAY Middle School youth group, Mon @6:30pm JANUARY 24, 2021 Boy Scouts, Tues @7pm Kids4Christ, Tuesday @4:30pm HS Youth Group, Weds @ 6:30pm Women’s Wednesday bible studies @9:30am Men’s Bible Study group, Thurs @6:30am Girls Basketball, Fri @ 5pm AA Meeting, Sat @7:30pm Youth Winter Calendar: Please watch this space, and our website calendar, for information on upcoming events. Possible winter retreat or day event in February being planned. • Middle school and High school youth group is up and running on Mondays and Wednesdays, with a HS bible study on Sunday evenings. Times and info can be found on our website. • We have 2 winter retreats being planned as follows: HS Ski trip on February 19-21 (location TBD) and the annual MS trip to Roundtop, March 5-6. More details will be sent out via e-letter as well as during the youth group so please stay tuned. Our Sunday school adult classes are back this Sunday. We have a ladies class led by Sandy Currin from a book called, “Life Giving Leaders”, and Dan Zagone A is leading a class on sermon discussion each week. So grab a coffee, and stay for “Paul, Plan, some good discussion after the service. Winter weather reminder: In the event that we do have snow or icy conditions this winter, and decide to cancel worship, cancellation information will be sent out an via email the morning of, and can also be found on our website, and our church & Epistle” answering machine. -

SAINT BASIL the GREAT ALTAR SERVER MANUAL Prayers of An

SAINT BASIL THE GREAT ALTAR SERVER MANUAL Prayers of an Altar Server O God, You have graciously called me to serve You upon Your altar. Grant me the graces that I need to serve You faithfully and wholeheartedly. Grant too that while serving You, may I follow the example of St. Tarcisius, who died protecting the Eucharist, and walk the same path that led him to Heaven. St. Tarcisius, pray for me and for all servers. ALTAR SERVER'S PRAYER Loving Father, Creator of the universe, You call Your people to worship, to be with You and each other at Mass. Help me, for You have called me also. Keep me prayerful and alert. Help me to help others in prayer. Thank you for the trust You've placed in me. Keep me true to that trust. I make my prayer in Jesus' name, who is with us in the Holy Spirit. Amen. 1 PLEASE SIGN AND RETURN THIS TOP SHEET IMMEDIATELY To the Parent/ Guardian of ______________________________(server): Thank you for supporting your child in volunteering for this very important job as an Altar Server. Being an Altar Server is a great honor – and a responsibility. Servers are responsible for: a) knowing when they are scheduled to serve, and b) finding their own coverage if they cannot attend. (email can help) The schedule is emailed out, prior to when it begins. The schedule is available on the Church website, and published the week before in the Church Bulletin. We have attached the, “St. Basil Altar Server Manual.” After your child attends the two server training sessions, he/she will most likely still feel unsure about the job – that’s OK. -

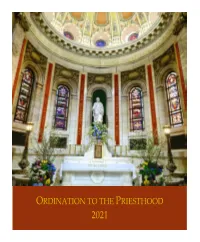

ORDINATION 2021.Pdf

WELCOME TO THE CATHEDRAL OF SAINT PAUL Restrooms are located near the Chapel of Saint Joseph, and on the Lower Level, which is acces- sible via the stairs and elevator at either end of the Narthex. The Mother Church for the 800,000 Roman Catholics of the Archdiocese of Saint Paul and Minneapolis, the Cathedral of Saint Paul is an active parish family of nearly 1,000 households and was designated as a National Shrine in 2009. For more information about the Cathedral, visit the website at www.cathedralsaintpaul.org ARCHDIOCESE OF SAINT PAUL AND MINNEAPOLIS SAINT PAUL, MINNESOTA Cover photo by Greg Povolny: Chapel of Saint Joseph, Cathedral of Saint Paul 2 Archdiocese of Saint Paul and Minneapolis Ordination to the Priesthood of Our Lord Jesus Christ E Joseph Timothy Barron, PES James Andrew Bernard William Duane Duffert Brian Kenneth Fischer David Leo Hottinger, PES Michael Fredrik Reinhardt Josh Jacob Salonek S May 29, 2021 ten o’clock We invite your prayerful silence in preparation for Mass. ORGAN PRELUDE Dr. Christopher Ganza, organ Vêpres du commun des fêtes de la Sainte Vierge, op. 18 Marcel Dupré Ave Maris Stella I. Sumens illud Ave Gabrielis ore op. 18, No. 6 II. Monstra te esse matrem: sumat per te preces op. 18, No. 7 III. Vitam praesta puram, iter para tutum: op. 18, No. 8 IV. Amen op. 18, No. 9 3 HOLY MASS Most Rev. Bernard A. Hebda, Celebrant THE INTRODUCTORY RITES INTROITS Sung as needed ALL PLEASE STAND Priests of God, Bless the Lord Peter Latona Winner, Rite of Ordination Propers Composition Competition, sponsored by the Conference of Roman Catholic Cathedral Musicians (2016) ANTIPHON Cantor, then Assembly; thereafter, Assembly Verses Daniel 3:57-74, 87 1. -

Mass Coordinator Checklist for the Historic Church Before Mass • Arrive at Least 30 Minutes Prior to the Start of Mass

MC Checklist for the Historic Church October 2013 Mass Coordinator Checklist for the Historic Church Before Mass • Arrive at least 30 minutes prior to the start of Mass. • Take down the chain across the parking lot. • Unlock door of church. • Turn on interior lights and any appropriate exterior lights. • For a weekend Mass check the MC/Greeter/Usher notes (found on the Offertory table - cabinet behind pews on the left side of aisle) for any updates or changes for that Mass. • Turn the sound system on (located in the wooden cabinet in the Adoration Room). The button on the right of each box needs to be pushed in. You will know if they are both on if they turn green. Note that the button on the smaller device on top has to be pushed in for a few seconds before it turns green. • To check if they are both on properly see if the green light is on by the bottom of the microphone on the ambo. Lectionary • Turn on the fans if necessary. The switches for the fan are located in the same cabinet as the sound system. The switch to the left controls the speed of the fan. Fan Placard • Turn the altar and sanctuary lights on (switches are labeled inside the Adoration Room). • Turn the thermostat (by the sacristy door) up to 68 degrees. • For weekend Masses check the Presider’s Schedule to see who is celebrating (taped to the small refrigerator in the sacristy). If Fr. Frazier is not presiding or not has not yet arrived, get the appropriate vestments from the Parish Center and hang on the back of the door of Sacristy. -

Mass of Ordination to the Holy Priesthood June 27, 2020

Mass of Ordination To the Holy Priesthood June 27, 2020 Prayer for the Holy Father O God who in your providential design willed that your Church be built upon blessed Peter, whom you set over the other Apostles, look with favor, we pray, on Francis our Pope and grant that he, whom you have made Peter’s successor, may be for your people a visible source and foundation of unity in faith and of communion. Through our Lord Jesus Christ, your Son, who lives and reigns with you in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Excerpt from the English Translation of the Roman Missal ©2011, ICEL, All rights reserved. Most Reverend Michael R. Cote, D.D. Bishop of Norwich Prayer for the Bishop O God, eternal shepherd of the faithful, who tend your Church in countless ways and rule over her in love, grant, we pray, that Michael, your servant, whom you have set over your people, may preside in the place of Christ over the flock whose shepherd he is, and be faithful as a teacher of doctrine, a Priest of sacred worship and as one who serves them by governing. Through our Lord Jesus Christ, your Son, who lives and reigns with you in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Excerpt from the English translation of the Roman Missal ©2011, ICEL, All rights reserved 1 CELEBRATION OF THE ORDINATION TO THE PRIESTHOOD OF Reverend Michael Patrick Bovino for Service as Priest of the Diocese of Norwich Ritual Mass for the Conferral of Holy Orders Cathedral of Saint Patrick Norwich, Connecticut June 27, 2020 10:30 a.m. -

Church and Liturgical Objects and Terms

Church and Liturgical Objects and Terms Liturgical Objects Used in Church The chalice: The The paten: The vessel which golden “plate” that holds the wine holds the bread that that becomes the becomes the Sacred Precious Blood of Body of Christ. Christ. The ciborium: A The pyx: golden vessel A small, closing with a lid that is golden vessel that is used for the used to bring the distribution and Blessed Sacrament to reservation of those who cannot Hosts. come to the church. The purificator is The cruets hold the a small wine and the water rectangular cloth that are used at used for wiping Mass. the chalice. The lavabo towel, The lavabo and which the priest pitcher: used for dries his hands after washing the washing them during priest's hands. the Mass. The corporal is a square cloth placed The altar cloth: A on the altar beneath rectangular white the chalice and cloth that covers paten. It is folded so the altar for the as to catch any celebration of particles of the Host Mass. that may accidentally fall The altar A new Paschal candles: Mass candle is prepared must be and blessed every celebrated with year at the Easter natural candles Vigil. This light stands (more than 51% near the altar during bees wax), which the Easter Season signify the and near the presence of baptismal font Christ, our light. during the rest of the year. It may also stand near the casket during the funeral rites. The sanctuary lamp: Bells, rung during A candle, often red, the calling down that burns near the of the Holy Spirit tabernacle when the to consecrate the Blessed Sacrament is bread and wine present there. -

Beyond the Bosphorus: the Holy Land in English Reformation Literature, 1516-1596

BEYOND THE BOSPHORUS: THE HOLY LAND IN ENGLISH REFORMATION LITERATURE, 1516-1596 Jerrod Nathan Rosenbaum A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2019 Approved by: Jessica Wolfe Patrick O’Neill Mary Floyd-Wilson Reid Barbour Megan Matchinske ©2019 Jerrod Nathan Rosenbaum ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Jerrod Rosenbaum: Beyond the Bosphorus: The Holy Land in English Reformation Literature, 1516-1596 (Under the direction of Jessica Wolfe) This dissertation examines the concept of the Holy Land, for purposes of Reformation polemics and apologetics, in sixteenth-century English Literature. The dissertation focuses on two central texts that are indicative of two distinct historical moments of the Protestant Reformation in England. Thomas More's Utopia was first published in Latin at Louvain in 1516, roughly one year before the publication of Martin Luther's Ninety-Five Theses signaled the commencement of the Reformation on the Continent and roughly a decade before the Henrician Reformation in England. As a humanist text, Utopia contains themes pertinent to internal Church reform, while simultaneously warning polemicists and ecclesiastics to leave off their paltry squabbles over non-essential religious matters, lest the unity of the Church catholic be imperiled. More's engagement with the Holy Land is influenced by contemporary researches into the languages of that region, most notably the search for the original and perfect language spoken before the episode at Babel. As the confusion of tongues at Babel functions etiologically to account for the origin of all ideological conflict, it was thought that the rediscovery of the prima lingua might resolve all conflict. -

Altar Server Instructions Booklet

Christ the King Catholic Church ALTAR SERVER INSTRUCTIONS Revised May, 2012 - 1 - Table of Contents Overview – All Positions ................................................................................................................ 4 Pictures of Liturgical Items ............................................................................................................. 7 Definition of Terms: Liturgical Items Used At Mass ..................................................................... 8 Helpful Hints and Red Cassocks................................................................................................... 10 1st Server Instructions ................................................................................................................. 11 2nd Server Instructions ................................................................................................................ 14 Crucifer Instructions .................................................................................................................... 17 Special Notes about FUNERALS ................................................................................................ 19 BENEDICTION .......................................................................................................................... 23 - 2 - ALTAR SERVER INSTRUCTIONS Christ the King Church OVERVIEW INTRODUCTION First of all, THANK YOU for answering God’s call to assist at Mass. You are now one of the liturgical ministers, along with the priest, deacon, lector and Extraordinary