Foul Ball: Major League Baseball's Cba Exploits

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September 17, 2020 at PNC Park, Pittsburgh, PA -- GAME #49/HOME #24 RHP DAKOTA HUDSON (3-2, 2.92 ERA) Vs. LHP STEVEN BRAULT (0-3, 4.73 ERA)

ST. LOUIS CARDINALS (22-23) VS. PITTSBURGH PIRATES (14-34) September 17, 2020 at PNC Park, Pittsburgh, PA -- GAME #49/HOME #24 RHP DAKOTA HUDSON (3-2, 2.92 ERA) vs. LHP STEVEN BRAULT (0-3, 4.73 ERA) THE PIRATES...have lost a season-high eight games in a row after winning two straight and four-of-six...Went 4-16 in their first 20 games and 10-10 in their middle 20; have gone 0-8 in their final 20...Have gone 12-19 against the N.L. Central and 2-15 against the A.L. Central...Were 25-23 after 48 games in 2019 (25-24 after 49). BUCS WHEN... LET’S TAKE FIVE: This series with the Cardinals marks the first time the two teams are playing a five-game series since doing Last five games ................0-5 so at PNC Park in 2013...The Bucs won the first four games of that series from 7/29-31 (doubleheader on 7/30) before losing the finale on 8/1...The last five-game series for the Bucs came against the Brewers at PNC Park in 2018 with the Pirates Last ten games .................2-8 winning all five games leading up to the All-Star break; 7/12-15 with a doubleheader on the 14th. Leading after 6 .................8-3 STUFF ON STEVEN: Steven Brault is making his 99th Major League appearance tonight (44th start)...He has posted a 3.71 ERA (26.2ip/12r/11er) in his eight starts this season, having been charged with zero earned runs five times...Steve is winless Tied after 6 ....................2-5 (0-6) in 13 appearances (12 starts) since winning his last big league game on 9/1/19...In 20 career starts at PNC Park, Brault Trailing after 6 ................4-26 has gone 1-6 with a 4.07 ERA, winning his lone decision here on 4/5/18 vs. -

2014 All-American Release Spring 5-29-14.Indd

The Voice Of Amateur Baseball Collegiate Post Office: P.O. Box 50566, Tucson, AZ 85703 Overnight Shipping: 2515 N. Stone Ave., Tucson, AZ 85705 Main Telephone: (520) 623-4530 FAX Line: (520) 624-5501 Baseball E-Mail: [email protected] Web Site: www.baseballnews.com Contact: Lou Pavlovich, Jr. Collegiate Baseball Newspaper Office: (520) 623-4530 For Immediate Release: Thursday, May 29, 2014 NCAA Division I All-Americans TUCSON, Ariz. — The Louisville Slugger NCAA Division I All-American baseball teams and National Player of The Year were announced today by Collegiate Baseball newspaper. The 17-man first team, chosen by performances up to regional playoffs and picked by the staff of Collegiate Baseball newspaper, features 11 conference players or pitchers of the year, including: • RHP Aaron Nola, Louisiana St. (Pitcher of Year Southeastern Conference). • LHP Jace Fry, Oregon St. (Pitcher of Year Pac-12 Conference). • RHP Andrew Morales, U.C. Irvine (Pitcher of Year Big West). • LHP Nathan Kirby, Virginia (Co-Pitcher of Year Atlantic Coast Conference). • LHP Chris Diaz, Miami, Fla. (Co-Pitcher of Year Atlantic Coast Conference). • C Max Pentecost, Kennesaw St. (Player of Year Atlantic Sun Conference). • 1B Casey Gillaspie, Wichita St. (Player of Year Missouri Valley Conference). • 2B Jace Conrad, Louisiana-Lafayette (Player of Year Sun Belt Conference). • OF Michael Conforto, Oregon St. (Player of Year Pac-12 Conference). • OF Michael Katz, William & Mary (Player of Year Colonial Athletic Association). • UT A.J. Reed, Kentucky (Player of Year Southeastern Conference). Kentucky’s A.J. Reed is Collegiate Baseball’s National Player Of The Year after one of the best seasons in college baseball history. -

No Creen En Nadie

Expreso Comparte las noticias en Facebook Expresoweb Sábado 24 de Abril de 2021 Síguenos en Twitter @Expresoweb / Instagram @Expresomx TIRO CON ARCO HERMANAS VALENCIA VAN POR MEDALLAS Las hermanas sonorenses desarrollarse el domingo. Valencia Trujillo, Alejandra y Margarita, disputarán las finales Por su parte, la menor de la y las preseas doradas en la familia, Margarita, junto a su modalidad por Equipos Femenil, equipo, donde comparte créditos de arco recurvo y compuesto, salieron con el brazo en alto respectivamente, en la primera en la semifinal para llegar a la fase de la Copa Mundial de Tiro contienda de la medalla de oro con Arco. en Compuesto Femenil, la cual habrá de celebrarse el sábado. En acciones del viernes la mayor de ellas y dos veces olímpica, Por lo tanto, Alejandra Valencia Alejandra Valencia, al lado de sus saldrá tras dos medallas el compañeras Aída Román y Ana domingo pues después de Paula Vázquez, consiguieron que busque el oro en Equipos, victorias en los cuartos y en las reanudará las acciones de semifinales para avanzar a la Recurvo Individual en la fase de gran final de Recurvo Femenil a semifinales. Mira las galerías de fotos de este cuaderno en expreso.com.mx/accion.html Hoy edita esta sección Víctor López Mazón CCIÓN ¿Tienes algo que comentar? [email protected]. mx AP/EXPRESO Síguelos hoy Liga Alemana Dallas vs LA Lakers Wolfsburgo vs Dortmund 5:30 PM/ESPN 2 6:30 AM/Fox Sports Grandes Ligas Liga Francesa LA Angelinos en Houston Ramón Metz vs PSG 1:10 PM/Fox Sports Laureano conectó un 8:00 AM/ESPN 2 cuadran- Texas en Chicago MB gular soli- Liga Española 4:10 PM/Fox Sports tario en el Valencia vs Alavés partido. -

University of Nebraska Press Sports

UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA PRESS SPORTS nebraskapress.unl.edu | unpblog.com I CONTENTS NEW & SELECTED BACKLIST 1 Baseball 12 Sports Literature 14 Basketball 18 Black Americans in Sports History 20 Women in Sports 22 Football 24 Golf 26 Hockey 27 Soccer 28 Other Sports 30 Outdoor Recreation 32 Sports for Scholars 34 Sports, Media, and Society series FOR SUBMISSION INQUIRIES, CONTACT: ROB TAYLOR Senior Acquisitions Editor [email protected] SAVE 40% ON ALL BOOKS IN THIS CATALOG BY nebraskapress.unl.edu USING DISCOUNT CODE 6SP21 Cover credit: Courtesy of Pittsburgh Pirates II UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA PRESS BASEBALL BASEBALL COBRA “Dave Parker played hard and he lived hard. Cobra brings us on a unique, fantastic A Life of Baseball and Brotherhood journey back to that time of bold, brash, and DAVE PARKER AND DAVE JORDAN styling ballplayers. He reveals in relentless Cobra is a candid look at Dave Parker, one detail who he really was and, in so doing, of the biggest and most formidable baseball who we all really were.”—Dave Winfield players at the peak of Black participation “Dave Parker’s autobiography takes us back in the sport during the late 1970s and early to the time when ballplayers still smoked 1980s. Parker overcame near-crippling cigarettes, when stadiums were multiuse injury, tragedy, and life events to become mammoth bowls, when Astroturf wrecked the highest-paid player in the major leagues. knees with abandon, and when Blacks had Through a career and a life noted by their largest presence on the field in the achievement, wealth, and deep friendships game’s history. -

2020 Topps Chrome Sapphire Edition .Xls

SERIES 1 1 Mike Trout Angels® 2 Gerrit Cole Houston Astros® 3 Nicky Lopez Kansas City Royals® 4 Robinson Cano New York Mets® 5 JaCoby Jones Detroit Tigers® 6 Juan Soto Washington Nationals® 7 Aaron Judge New York Yankees® 8 Jonathan Villar Baltimore Orioles® 9 Trent Grisham San Diego Padres™ Rookie 10 Austin Meadows Tampa Bay Rays™ 11 Anthony Rendon Washington Nationals® 12 Sam Hilliard Colorado Rockies™ Rookie 13 Miles Mikolas St. Louis Cardinals® 14 Anthony Rendon Angels® 15 San Diego Padres™ 16 Gleyber Torres New York Yankees® 17 Franmil Reyes Cleveland Indians® 18 Minnesota Twins® 19 Angels® Angels® 20 Aristides Aquino Cincinnati Reds® Rookie 21 Shane Greene Atlanta Braves™ 22 Emilio Pagan Tampa Bay Rays™ 23 Christin Stewart Detroit Tigers® 24 Kenley Jansen Los Angeles Dodgers® 25 Kirby Yates San Diego Padres™ 26 Kyle Hendricks Chicago Cubs® 27 Milwaukee Brewers™ Milwaukee Brewers™ 28 Tim Anderson Chicago White Sox® 29 Starlin Castro Washington Nationals® 30 Josh VanMeter Cincinnati Reds® 31 American League™ 32 Brandon Woodruff Milwaukee Brewers™ 33 Houston Astros® Houston Astros® 34 Ian Kinsler San Diego Padres™ 35 Adalberto Mondesi Kansas City Royals® 36 Sean Doolittle Washington Nationals® 37 Albert Almora Chicago Cubs® 38 Austin Nola Seattle Mariners™ Rookie 39 Tyler O'neill St. Louis Cardinals® 40 Bobby Bradley Cleveland Indians® Rookie 41 Brian Anderson Miami Marlins® 42 Lewis Brinson Miami Marlins® 43 Leury Garcia Chicago White Sox® 44 Tommy Edman St. Louis Cardinals® 45 Mitch Haniger Seattle Mariners™ 46 Gary Sanchez New York Yankees® 47 Dansby Swanson Atlanta Braves™ 48 Jeff McNeil New York Mets® 49 Eloy Jimenez Chicago White Sox® Rookie 50 Cody Bellinger Los Angeles Dodgers® 51 Anthony Rizzo Chicago Cubs® 52 Yasmani Grandal Chicago White Sox® 53 Pete Alonso New York Mets® 54 Hunter Dozier Kansas City Royals® 55 Jose Martinez St. -

ESPN Fantasy Baseball Cheat Sheet: H2H Categories Leagues

ESPN Fantasy Baseball Cheat Sheet: H2H categories leagues Starting pitchers, cont. First basemen Shortstops Outfielders Outfielders, cont. 51. (203) Andrew Heaney LAA $2 1. (4) Cody Bellinger LAD $43 1. (7) Francisco Lindor CLE $39 1. (1) Mike Trout LAA $49 63. (238) David Peralta ARI $1 52. (205) Mike Foltynewicz ATL $2 2. (19) Freddie Freeman ATL $30 2. (9) Trea Turner WSH $36 2. (2) Christian Yelich MIL $48 64. (241) Mallex Smith SEA $1 53. (208) Brendan McKay TB $2 3. (29) Pete Alonso NYM $23 3. (10) Alex Bregman HOU $35 3. (3) Ronald Acuna Jr. ATL $47 65. (245) Shogo Akiyama CIN $1 54. (210) Ryan Yarbrough TB $2 4. (39) Anthony Rizzo CHC $21 4. (12) Trevor Story COL $33 4. (4) Cody Bellinger LAD $43 66. (246) Hunter Dozier KC $1 55. (212) Masahiro Tanaka NYY $2 5. (48) Matt Olson OAK $18 5. (25) Fernando Tatis Jr. SD $25 5. (6) Mookie Betts LAD $42 67. (251) Garrett Hampson COL $1 Last updated: 56. (217) Jake Odorizzi MIN $1 6. (51) Paul Goldschmidt STL $18 6. (31) Javier Baez CHC $23 6. (13) Bryce Harper PHI $33 68. (257) Willie Calhoun TEX $1 Friday, July 24, 2020 57. (219) German Marquez COL $1 7. (54) Josh Bell PIT $17 7. (33) Xander Bogaerts BOS $22 7. (15) J.D. Martinez BOS $32 69. (259) A.J. Pollock LAD $1 Position rank is listed first, followed by overall rank 58. (224) Jose Urquidy HOU $1 8. (63) Jose Abreu CWS $15 8. (34) Gleyber Torres NYY $22 8. -

Arizona Diamondbacks 2016 Spring Training Game Notes

ARIZONA DIAMONDBACKS 2016 SPRING TRAINING GAME NOTES dbacks.com losdbacks.com @Dbacks @LosDbacks facebook.com/D-backs Salt River Fields at Talking Stick 7555 N. Pima Road, Scottsdale, Ariz., 85258 ARIZONA WILDCATS (4-3) AT ARIZONA DIAMONDBACKS (0-0) PRESS.DBACKSMEDIA.COM Tuesday, March 1, 2016 ♦ Salt River Fields at Talking Stick ♦ Scottsdale, Ariz. ♦ 3:10 p.m. ♦Daily content includes media guides, game notes, statistical reports, - COLLEGIATE BASEBALL SERIES - lineups, press releases, etc.…please contact a D-backs’ Communica- RHP Michael Flynn (0-0, 21.60) vs. RHP Matt Koch (NR) tions staff member for the login/password. dbacks.com 2016 D-BACKS SPRING SCHEDULE (0-0) DIAMOND-FACTS ROSTER ROUNDUP WINNING LOSING DATE OPP RESULT REC. PITCHER PITCHER ATT. Arizona begins its 19th Cactus League season and sixth ♦ ♦Arizona opens Cactus League play with 68 players in 3/1 UofA 3:10 p.m dbacks.com at Salt River Fields at Talking Stick…Tucson was the Major League camp: 39 pitchers (10 left-handed), 7 3/2 @ COL 1:10 p.m. ESPN Radio 620 club’s spring headquarters from 1998-2010. catchers, 11 infi elders and 11 outfi elders. 3/3 COL 1:10 p.m. ♦D-backs are 301-280-19 all-time during Spring Train- ♦The D-backs return 22 players from its 40-man roster at 3/4 OAK (ss) 1:10 p.m. ing…in 2015, the D-backs went 19-14-2. the start of last Spring Training…Arizona returned 23 3/5 @ LAD 1:05 p.m. Arizona Sports 98.7 FM ♦Arizona’s 19 wins tied for the most in the NL, with New players in 2015 and 26 in 2014. -

2017 Topps Stadium Club Baseball BASE

2017 Topps Stadium Club Baseball BASE 1 Albert Almora Chicago Cubs® 2 Mike Moustakas Kansas City Royals® 3 Noah Syndergaard New York Mets® 4 Nelson Cruz Seattle Mariners™ 5 Aroldis Chapman New York Yankees® 6 Adam Jones Baltimore Orioles® 7 C.J. Cron Angels® 8 Yu Darvish Texas Rangers® 9 Greg Maddux Atlanta Braves™ 10 Danny Santana Minnesota Twins® 11 Harmon Killebrew Minnesota Twins® 12 JaCoby Jones Detroit Tigers® Rookie 13 Jake Thompson Philadelphia Phillies® 14 Ben Zobrist Chicago Cubs® 15 Jorge Soler Kansas City Royals® 16 Matt Harvey New York Mets® 17 Didi Gregorius New York Yankees® 18 Fernando Rodney Arizona Diamondbacks® 19 DJ LeMahieu Colorado Rockies™ 20 Dansby Swanson Atlanta Braves™ Rookie 21 Randy Johnson Arizona Diamondbacks® 22 Adam Duvall Cincinnati Reds® 23 Yasmany Tomas Arizona Diamondbacks® 24 Zack Greinke Arizona Diamondbacks® 25 Mark Melancon San Francisco Giants® 26 Eric Hosmer Kansas City Royals® 27 David Peralta Arizona Diamondbacks® 28 Joe Mauer Minnesota Twins® 29 John Smoltz Atlanta Braves™ 30 Danny Duffy Kansas City Royals® 31 Salvador Perez Kansas City Royals® 32 Brandon Phillips Atlanta Braves™ 33 Yadier Molina St. Louis Cardinals® 34 Greg Bird New York Yankees® 35 Nomar Mazara Texas Rangers® 36 Willson Contreras Chicago Cubs® 37 Jose Bautista Toronto Blue Jays® 38 Robert Gsellman New York Mets® 39 Bryce Harper Washington Nationals® 40 Jose Peraza Cincinnati Reds® 41 Kris Bryant Chicago Cubs® 42 Justin Verlander Detroit Tigers® 43 Jharel Cotton Oakland Athletics™ Rookie 44 Jacoby Ellsbury New York Yankees® -

Game Information

INDIANAPOLIS INDIANS GAME INFORMATION [ Indianapolis Indians501 //West Communications Maryland Department Street ] - Indianapolis, _______________________________________ IN 46225 ♦ (317) 269-3542 ♦ @IndyIndians ♦ IndyIndians.com/MediaKit Indianapolis Indians Wednesday, May 19, 2021 8:05 PM ET St. Paul Saints 8-4 (T-1st, -- GB, AAA-E MW) CHS Field ♦ St. Paul, MN 5-8 (5th, 3.5 GB, AAA-E MW) RHP Chad Kuhl (MLB Rehab) Game #13 / Road #7 RHP Chandler Shepherd (0-1, 9.82) RHP Cody Ponce (0-0, 5.87) Radio/TV: FoxSportsIndy.com / AM 1260 / iHeart app / MiLB TV 2021 at a glance indy bits series history Overall 8-4 2021 @ IND: 0-0 Home 5-1 LAST NIGHT: Facing a 1-0 deficit following the first inning, the Indians scored four runs in the second and three in the third en route to a decisive 7-3 Road 3-3 2021 @ STP: 1-0 Place T-1st win over St. Paul last night. Seven of the Indians nine starters recorded at least one hit and together the team tallied a season-high 11 base hits. Since 1938 @ IND: 131-116 (.530) GA/GB -- GB RHP Beau Sulser earned his second win of the season after surrendering three runs in 5.0 innings, and the Indians bullpen combined for four shutout Since 1938 @ STP: 110-136 (.447) Streak W4 Since 1938 Totals: 241-252 (.489) Home Streak W3 innings to hold the Saints at bay. Road Streak W1 Longest Winning Streak 4 2021 TEAM COMPARISON Longest Losing Streak 2 DUAL RBI DOUBLES: Anthony Alford and Hunter Owen, batting in the sixth and seventh spots of the Indians lineup respectively, each recorded two- Indians Saints Last 5 4-1 Last 10 7-3 RBI doubles in the win over St. -

Clips for 7-12-10

MEDIA CLIPS – Jan. 23, 2019 Walker short in next-to-last year on HOF ballot Former slugger receives 54.6 percent of vote; Helton gets 16.5 percent in first year of eligibility Thomas Harding | MLB.com | Jan. 22, 2019 DENVER -- Former Rockies star Larry Walker introduced himself under a different title during his conference call with Denver media on Tuesday: "Fifty-four-point-six here." That's the percentage of voters who checked Walker in his ninth year of 10 on the Baseball Writers' Association of America Hall of Fame ballot. It's a dramatic jump from his previous high, 34.1 percent last year -- an increase of 88 votes. However, he's going to need an 87-vote leap to reach the requisite 75 percent next year, his final season of eligibility. Jayson Stark of the Athletic noted during MLB Network's telecast that the only player to receive a jump of at least 80 votes in successive years was former Reds shortstop Barry Larkin, who was inducted in 2012. But when publicly revealed ballots had him approaching the mid-60s in percentage, Walker admitted feeling excitement he hadn't experienced in past years. "I haven't tuned in most years because there's been no chance of it really happening," Walker said. "It was nice to see this year, to watch and to have some excitement involved with it. "I was on Twitter and saw the percentages that were getting put out there for me. It made it more interesting. I'm thankful to be able to go as high as I was there before the final announcement." When discussing the vote, one must consider who else is on the ballot. -

Game Information Indianapolis Indians

game information indianapolis indians _______________________________________ [ Indianapolis Indians501 // CommunicationsWest Maryland Department Street ] - Indianapolis, IN 46225 ♦ (317) 269-3542 ♦ @IndyIndians ♦ IndyIndians.com/MediaKit[ IndyIndians.com // (317) 269-3524 ] Indianapolis Indians Friday, June 28, 2019 7:05 p.m. ET Gwinnett Stripers 41-36 (2nd, -6.5 GB, IL West) Coolray Field ♦ Lawrenceville, GA 43-35 (T-2nd, -4.5 GB, IL South) RHP Yefry Ramirez (1-2, 3.34) Game #78 // Road #39 RHP Kyle Wright (4-4, 6.08) Radio/TV: Fox Sports 97.5 / AM 1260 / iHeart app / MiLB TV UPCOMING MATCHUPS DAY DATE OPPONENT PROBABLES TIME (ET) RADIO/TV Saturday June 29 at Gwinnett RHP Mitch Keller (6-1, 2.89) vs. RHP Mike Foltynewicz (1-1, 6.11) 6:05 p.m. Fox Sports 97.5 / AM 1260 / iHeart app / MiLB TV Sunday June 30 at Gwinnett RHP Eduardo Vera (4-5, 5.66) vs. LHP Kolby Allard (6-3, 3.75) 1:05 p.m. Fox Sports 97.5 / AM 1260 / iHeart app / MiLB TV Monday July 1 at Louisville TBA vs. TBA 7:00 p.m. Fox Sports 97.5 / AM 1260 / iHeart app / MiLB TV Tuesday July 2 at Louisville RHP Alex McRae (5-4, 5.07) vs. TBA 7:00 p.m. Fox Sports 97.5 / AM 1260 / iHeart app / MiLB TV 2019 indy bits Tribe Tips 2019 AT A GLANCE Day Games: 13-11 Overall 41-36 Night Games: 28-25 LAST NIGHT: For a second consecutive night, the Indians had a chance to tie or win the game in their last at-bat but the Tribe fell short in the comeback Home 20-19 attempt, falling 3-2 to the first-place Clippers. -

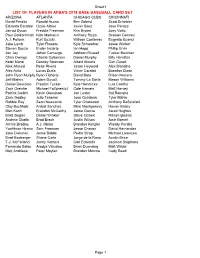

List of Players in Apba's 2018 Base Baseball Card

Sheet1 LIST OF PLAYERS IN APBA'S 2018 BASE BASEBALL CARD SET ARIZONA ATLANTA CHICAGO CUBS CINCINNATI David Peralta Ronald Acuna Ben Zobrist Scott Schebler Eduardo Escobar Ozzie Albies Javier Baez Jose Peraza Jarrod Dyson Freddie Freeman Kris Bryant Joey Votto Paul Goldschmidt Nick Markakis Anthony Rizzo Scooter Gennett A.J. Pollock Kurt Suzuki Willson Contreras Eugenio Suarez Jake Lamb Tyler Flowers Kyle Schwarber Jesse Winker Steven Souza Ender Inciarte Ian Happ Phillip Ervin Jon Jay Johan Camargo Addison Russell Tucker Barnhart Chris Owings Charlie Culberson Daniel Murphy Billy Hamilton Ketel Marte Dansby Swanson Albert Almora Curt Casali Nick Ahmed Rene Rivera Jason Heyward Alex Blandino Alex Avila Lucas Duda Victor Caratini Brandon Dixon John Ryan Murphy Ryan Flaherty David Bote Dilson Herrera Jeff Mathis Adam Duvall Tommy La Stella Mason Williams Daniel Descalso Preston Tucker Kyle Hendricks Luis Castillo Zack Greinke Michael Foltynewicz Cole Hamels Matt Harvey Patrick Corbin Kevin Gausman Jon Lester Sal Romano Zack Godley Julio Teheran Jose Quintana Tyler Mahle Robbie Ray Sean Newcomb Tyler Chatwood Anthony DeSclafani Clay Buchholz Anibal Sanchez Mike Montgomery Homer Bailey Matt Koch Brandon McCarthy Jaime Garcia Jared Hughes Brad Ziegler Daniel Winkler Steve Cishek Raisel Iglesias Andrew Chafin Brad Brach Justin Wilson Amir Garrett Archie Bradley A.J. Minter Brandon Kintzler Wandy Peralta Yoshihisa Hirano Sam Freeman Jesse Chavez David Hernandez Jake Diekman Jesse Biddle Pedro Strop Michael Lorenzen Brad Boxberger Shane Carle Jorge de la Rosa Austin Brice T.J. McFarland Jonny Venters Carl Edwards Jackson Stephens Fernando Salas Arodys Vizcaino Brian Duensing Matt Wisler Matt Andriese Peter Moylan Brandon Morrow Cody Reed Page 1 Sheet1 COLORADO LOS ANGELES MIAMI MILWAUKEE Charlie Blackmon Chris Taylor Derek Dietrich Lorenzo Cain D.J.