Hatchet Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

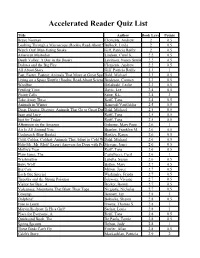

Accelerated Reader Quiz List

Accelerated Reader Quiz List Title Author Book Level Points Brave Norman Clements, Andrew 2 0.5 Looking Through a Microscope (Rookie Read-About Science)Bullock, Linda 2 0.5 Watch Out! Man-Eating Snake Giff, Patricia Reilly 2 0.5 American Mastodon Lindeen, Carol K. 2.2 0.5 Death Valley: A Day in the Desert Levinson, Nancy Smiler 2.2 0.5 Dolores and the Big Fire Clements, Andrew 2.2 0.5 All About Stacy Giff, Patricia Reilly 2.3 1 Fast, Faster, Fastest: Animals That Move at Great SpeedsDahl, Michael 2.3 0.5 Living on a Space Shuttle (Rookie Read-About Science)Bredeson, Carmen 2.3 0.5 Woolbur Helakoski, Leslie 2.3 0.5 Feeding Time Davis, Lee 2.4 0.5 Phone Calls Stine, R.L. 2.4 3 Take Away Three Reiff, Tana 2.4 0.5 Animals in Winter Bancroft/VanGelder 2.5 0.5 Deep, Deeper, Deepest: Animals That Go to Great DepthsDahl, Michael 2.5 0.5 Juan and Lucy Reiff, Tana 2.5 0.5 Just for Today Reiff, Tana 2.5 0.5 Afternoon on the Amazon Osborne, Mary Pope 2.6 1 Air Is All Around You Branley, Franklyn M. 2.6 0.5 Cockroach (Bug Books) Hartley, Karen 2.6 0.5 Cold, Colder, Coldest: Animals That Adapt to Cold WeatherDahl, Michael 2.6 0.5 Help Me, Mr. Mutt! Expert Answers for Dogs with PeopleStevens, Problems Janet 2.6 0.5 Mollie's Year Reiff, Tana 2.6 0.5 Plain Janes, The Castellucci, Cecil 2.6 1 Washington Labella, Susan 2.6 0.5 Baby Wolf Batten, Mary 2.7 0.5 Big Cats Milton, Joyce 2.7 0.5 Each One Special Wishinsky, Frieda 2.7 0.5 Timothy and the Strong Pajamas Schwarz, Viviane 2.7 0.5 Visitor for Bear, A Becker, Bonny 2.7 0.5 Volcanoes: Mountains That Blow Their Tops Nirgiotis, Nicholas 2.7 0.5 Coverup Bennett, Jay 2.8 3 Dolphins! Bokoske, Sharon 2.8 0.5 Free to Learn Owens, Thomas S. -

Gary Paulsen Author Study OR

Gary Paulsen ONLINE RESOURCES PACKET AuthorStudy Grade 5 Copyright © 2010 Pearson Education, Inc., or its affiliates. All Rights Reserved. Printed in the United States of America. This publication is protected by copyright, and permission should be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction, storage in a retrieval system, or transmission in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or likewise. The publisher hereby grants permission to reproduce these pages, in part or in whole, for classroom use only, the number not to exceed the number of students in each class. Notice of copyright must appear on all copies. For information regarding permissions, write to Pearson Curriculum Group Rights & Permissions, One Lake Street, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey 07458. ISBN 13: 978-0-66363-989-2 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 14 13 12 11 10 Resources Gary Paulsen ASSESSMENT AND PROGRESS MONITORING Monitoring Student Progress Writing an Opinion (Pre-Assessment Prompt) Writing an Opinion (Post-Assessment Prompt) Rubric: Elements to Include in an Opinion LESSON RESOURCES Frontloading Lesson 1: Gary Paulsen Author Profile Notes/Thinking Frontloading Lesson 2: Mind Map Mind Map (completed sample) Frontloading Lesson 3: Facts/Questions/Responses Frontloading Lesson 4: Character’s Experience Lesson 2: The American Revolution Lesson 4 The Thirteen English Colonies Lesson 5: Checkpoint 1: Reader’s Notebook Entry Lesson 6: Model Response for Checkpoint 1 Sharing Writing Homework Lesson 7: People Watcher’s Sheet Recent -

Crystal Reports Activex Designer

Quiz List—Reading Practice Page 1 Printed Wednesday, March 18, 2009 2:36:33PM School: Churchland Academy Elementary School Reading Practice Quizzes Quiz Word Number Lang. Title Author IL ATOS BL Points Count F/NF 9318 EN Ice Is...Whee! Greene, Carol LG 0.3 0.5 59 F 9340 EN Snow Joe Greene, Carol LG 0.3 0.5 59 F 36573 EN Big Egg Coxe, Molly LG 0.4 0.5 99 F 9306 EN Bugs! McKissack, Patricia C. LG 0.4 0.5 69 F 86010 EN Cat Traps Coxe, Molly LG 0.4 0.5 95 F 9329 EN Oh No, Otis! Frankel, Julie LG 0.4 0.5 97 F 9333 EN Pet for Pat, A Snow, Pegeen LG 0.4 0.5 71 F 9334 EN Please, Wind? Greene, Carol LG 0.4 0.5 55 F 9336 EN Rain! Rain! Greene, Carol LG 0.4 0.5 63 F 9338 EN Shine, Sun! Greene, Carol LG 0.4 0.5 66 F 9353 EN Birthday Car, The Hillert, Margaret LG 0.5 0.5 171 F 9305 EN Bonk! Goes the Ball Stevens, Philippa LG 0.5 0.5 100 F 7255 EN Can You Play? Ziefert, Harriet LG 0.5 0.5 144 F 9314 EN Hi, Clouds Greene, Carol LG 0.5 0.5 58 F 9382 EN Little Runaway, The Hillert, Margaret LG 0.5 0.5 196 F 7282 EN Lucky Bear Phillips, Joan LG 0.5 0.5 150 F 31542 EN Mine's the Best Bonsall, Crosby LG 0.5 0.5 106 F 901618 EN Night Watch (SF Edition) Fear, Sharon LG 0.5 0.5 51 F 9349 EN Whisper Is Quiet, A Lunn, Carolyn LG 0.5 0.5 63 NF 74854 EN Cooking with the Cat Worth, Bonnie LG 0.6 0.5 135 F 42150 EN Don't Cut My Hair! Wilhelm, Hans LG 0.6 0.5 74 F 9018 EN Foot Book, The Seuss, Dr. -

Olentangy Local School District Literature Selection Review

Olentangy Local School District Literature Selection Review Teacher: Byard/DeGiorgio School: Hyatts Middle School Book Title: Nightjohn Genre: historical fiction Author: Gary Paulsen Pages: 112 Publisher: Laurel Leaf Copyright: 1995 In a brief rationale, please provide the following information relative to the book you would like added to the school’s book collection for classroom use. You may attach additional pages as needed. Book Summary and summary citation: (suggested resources include book flap summaries, review summaries from publisher, book vendors, etc.) Sarny, a female slave at the Waller plantation, first sees Nightjohn when he is brought there with a rope around his neck, his body covered in scars. He had escaped north to freedom, but he came back--came back to teach reading. Knowing that the penalty for reading is dismemberment Nightjohn still retumed to slavery to teach others how to read. And twelve-year-old Sarny is willing to take the risk to learn. Set in the 1850s, Gary Paulsen's groundbreaking new novel is unlike anything else the award- winning author has written. It is a meticulously researched, historically accurate, and artistically crafted portrayal of a grim time in our nation's past, brought to light through the personal history of two unforgettable characters. Provide an instructional rationale for the use of this title, including specific reference to the OLSD curriculum map(s): (Curriculum maps may be referenced by grade/course and indicator number or curriculum maps with indicators highlighted may be attached to this form) CCS #1-10 Reading Literature Include two professional reviews of this title: (a suggested list of resources for identifying professional reviews is shown below. -

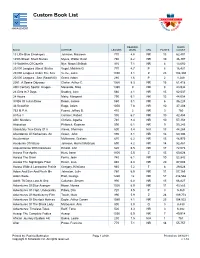

Custom Book List

Custom Book List MANAGEMENT READING WORD BOOK AUTHOR LEXILE® LEVEL GRL POINTS COUNT 13 Little Blue Envelopes Johnson, Maureen 770 4.8 NR 15 62,401 145th Street: Short Stories Myers, Walter Dean 760 6.2 NR 10 36,397 19 Varieties Of Gazelle Nye, Naomi Shihab 910 7.1 NR 6 13,050 20,000 Leagues (Great Illustra Vogel, Malvina G. 770 4.7 P 6 16,431 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea Verne, Jules 1030 8.1 Z 23 106,330 20,000 Leagues...Sea (Read180) Grant, Adam 280 1.6 P 2 1,289 2001, A Space Odyssey Clarke, Arthur C. 1060 8.3 NR 15 61,418 20th Century Sports: Images... Meserole, Mike 1380 9 NR 8 23,934 24 Girls In 7 Days Bradley, Alex 680 4.1 NR 15 62,537 24 Hours Mahy, Margaret 790 6.1 NR 12 44,054 3 NBs Of Julian Drew Deem, James 560 5.1 NR 6 36,224 33 Snowfish Rapp, Adam 1050 7.8 NR 10 37,208 763 M.P.H. Fuerst, Jeffrey B. 410 2 NR 3 760 8 Plus 1 Cormier, Robert 930 6.7 NR 10 42,484 ABC Murders Christie, Agatha 740 8.4 NR 10 57,358 Abduction Philbrick, Rodman 590 6.1 NR 9 55,243 Absolutely True Diary Of A Alexie, Sherman 600 3.4 N/A 13 44,264 Abundance Of Katherines, An Green, John 890 8.1 NR 16 60,306 Acceleration McNamee, Graham 670 6.2 NR 13 46,975 Accidents Of Nature Johnson, Harriet McBryde 690 4.2 NR 14 52,481 Acquaintance With Darkness Rinaldi, Ann 520 6.5 NR 17 72,073 Across Five Aprils Hunt, Irene 1100 5.5 Z 15 60,628 Across The Grain Ferris, Jean 740 6.1 NR 10 52,842 Across The Nightingale Floor Hearn, Lian 840 6.4 NR 20 87,008 Across Wide & Lonesome Prairie Gregory, Kristiana 940 5.2 T 8 29,628 Adam And Eve And Pinch Me Johnston, Julie 760 6.5 NR 11 57,165 Adam Bede Eliot, George 1260 12 NR 57 216,566 Adrift: 76 Days Lost At Sea Callahan, Steven 990 6.8 NR 15 66,827 Adventures Of Blue Avenger Howe, Norma 1020 6.9 NR 11 43,553 Adventures Of Capt. -

Full Book List

Title Author or Editor The 100 The 50 1994 - 1998 - Modern NCTE Walden Gay, Gay, Banned Banned Gay, Most Most 1995 1999 Library Pre- books Lesbian, Lesbian or and Lesbian, - A List of Lists of books that have been challenged Chllg'd Chllg'd (85) Best package promo and Bi; children Chllg'd Chllg'd and Bi; or are controversial 90-99 90-92 (159) of 20th d (51) Younker s books; in in multiple - Books on this list may or may not be appropriate century challeng (84) Betts Wiscons Texas sources for your child (34) e (32) in (53) (125) (266) - The sources used in developing this List of Lists respons are noted at the end e (713) 1984 Orwell, George XXX 100 Questions and Answers About AIDS Ford, Michael Thomas XX 101 Ways To Bug Your Parents Wardlow, Lee X 365 Days Glasser, Ronald J. X A Blue Eyed Daisy Rylant, Cynthia X A Boy's Own Story White, Edmund X A Break with Charity Rinaldi, Ann X A Brother's Touch Levy, Owen X A Candle For Saint Antony Spence, Eleanor X A Child Called "It" Pelzer, Dave X A Circle Unbroken Hotze, Sollace X A Clockwork Orange Burgess Anthony XXX A Day No Pigs Would Die Peck, Robert 16 17 X X XX A Face in Every Window Nolan, Han X X A Farewell to Arms Hemmingway, Ernest XXX A Gathering Of Old Men Gaines, Ernst J. X A Girl Named Disaster Farmer, Nancy X A Hero Ain't Nothin' but a Sandwich Childress, Alice X A House Like a Lotus L'Engle, Madeleine X A Killing Freeze Hall, Lynn X A Knight Without Armor Kilcher, Jewel X A Life For A Life Hill, Ernest X A Light In The Attic Silverstein, Shel 51 X X A Need To Kill Pettit, Mark -

III. Adopt the Agenda of the Regular Meeting of June 20. 2018 VIII

BOARD MEETING: Regular DATE: Wednesday, June 20,2018 TIME: 6:30 p.m. PLACE: Naples High School Cafeteria I. Meeting Called to Order II. Roll Call III. Adopt the Agenda of the Regular Meeting of June 20. 2018 (Board Action) IV. Executive Session (Board Action) V. Pledge of Allegiance VI. Public Comments: The Board of Education invites you, the residents of our school community, to feel comfortable in sharing matters of interest or concern that you might have with us. The Board President will be happy to recognize those of you who wish to speak. We would ask that you come forward and please identity yourself before presenting your thoughts. Those items brought to the attention of the Board during this time may be taken under consideration for future response or action. {Individual comments will be limited to three minutes.) As a matter of courtesy, we ask that issues related to specific School District personnel or students be brought to the attention of the Superintendent of Schools privately. Thank you for this consideration. Board Response: The Board of Education is committed to keeping communication open and transparent. The Board of Education President will be working with the Board and the Superintendent to make every effort to respond to public comments directed to the Board of Education at previous meetings, during the next scheduled meeting. VII. Points of Interest VIII. Superintendent Recognitions & Updates • Welcome Owen Keimedy Have a Great Summer • Handbook for Coaches IX. Administrative Reports • Elementary Principal Director of Pupil Personnel Services • Secondary Principal X. Contractual Agreement • Superintendent's Contract (Board Action) . -

Accelerated Reader List

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. Level 43532 1 Is One Tudor, Tasha 2.1 0.5 EN 1209 EN 100 Acorns Palazzo-Craig, Janet 2.0 0.5 57450 100 Days of School Harris, Trudy 2.3 0.5 EN 41025 100th Day of School, The Medearis, Angela Shelf 1.4 0.5 EN 35821 100th Day Worries Cuyler, Margery 3.0 0.5 EN 61265 12 Again Corbett, Sue 4.9 8.0 EN 74604 13: Thirteen Stories...Agony and Ecstasy of Being Howe, James 5.0 9.0 EN Thirteen 14796 13th Floor: A Ghost Story, The Fleischman, Sid 4.4 4.0 EN 107287 15 Minutes Young, Steve 4.0 4.0 EN 661 EN 18th Emergency, The Byars, Betsy 4.7 4.0 9801 EN 1980 U.S. Hockey Team Coffey, Wayne 6.4 1.0 5976 EN 1984 Orwell, George 8.9 17.0 523 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Unabridged) Verne, Jules 10.0 28.0 34791 2001: A Space Odyssey Clarke, Arthur C. 9.0 12.0 EN 11592 2095 Scieszka, Jon 3.8 1.0 EN 6651 EN 24-Hour Genie, The McGinnis, Lila Sprague 3.3 1.0 593 EN 25 Cent Miracle, The Nelson, Theresa 5.6 7.0 30629 26 Fairmount Avenue De Paola, Tomie 4.4 1.0 EN 166 EN 4B Goes Wild Gilson, Jamie 4.6 4.0 9001 EN 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins, The Seuss, Dr. 4.0 1.0 413 EN 89th Kitten, The Nilsson, Eleanor 4.7 2.0 71428 95 Pounds of Hope Gavalda, Anna 4.3 2.0 EN 68579 "A" My Name Is Alice Bayer, Jane 2.2 0.5 Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. -

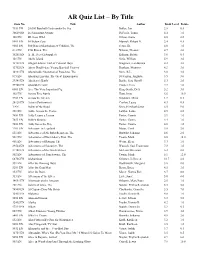

Accelerated Reader Quiz List

AR Quiz List – By Title Quiz No. Title Author Book Level Points 7351 EN 20,000 Baseball Cards under the Sea Buller, Jon 2.5 0.5 30629 EN 26 Fairmount Avenue DePaola, Tomie 4.4 1.0 166 EN 4B Goes Wild Gilson, Jamie 4.6 4.0 8001 EN 50 Below Zero Munsch, Robert N. 2.4 0.5 9001 EN 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins, The Seuss, Dr. 4.0 1.0 413 EN 89th Kitten, The Nilsson, Eleanor 4.7 2.0 16201 EN A...B...Sea (Crabapples) Kalman, Bobbie 3.6 0.5 101 EN Abel's Island Steig, William 5.9 3.0 13701 EN Abigail Adams: Girl of Colonial Days Wagoner, Jean Brown 4.2 3.0 13702 EN Abner Doubleday: Young Baseball Pioneer Dunham, Montrew 4.2 3.0 14931 EN Abominable Snowman of Pasadena, The Stine, R.L. 3.0 3.0 815 EN Abraham Lincoln: The Great Emancipator Stevenson, Augusta 3.5 3.0 29341 EN Abraham's Battle Banks, Sara Harrell 5.3 2.0 39788 EN Absolutely Lucy Cooper, Ilene 2.7 1.0 6001 EN Ace: The Very Important Pig King-Smith, Dick 5.2 3.0 102 EN Across Five Aprils Hunt, Irene 6.6 10.0 7201 EN Across the Stream Ginsburg, Mirra 1.7 0.5 28128 EN Actors (Performers) Conlon, Laura 4.3 0.5 1 EN Adam of the Road Gray, Elizabeth Janet 6.5 9.0 301 EN Addie Across the Prairie Lawlor, Laurie 4.9 4.0 7651 EN Addy Learns a Lesson Porter, Connie 3.9 1.0 7653 EN Addy's Surprise Porter, Connie 4.4 1.0 7652 EN Addy Saves the Day Porter, Connie 4.0 1.0 7701 EN Adventure in Legoland Matas, Carol 3.8 2.0 451 EN Adventures of Ali Baba Bernstein, The Hurwitz, Johanna 4.6 2.0 501 EN Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The Twain, Mark 6.6 18.0 401 EN Adventures of Ratman, The Weiss, Ellen 3.3 1.0 29524 EN Adventures of Sojourner, The Wunsch, Susi Trautmann 7.8 1.0 21748 EN Adventures of the Greek Heroes McLean/Wiseman 6.2 4.0 502 EN Adventures of Tom Sawyer, The Twain, Mark 8.1 12.0 68706 EN Afghanistan Gritzner, Jeffrey A. -

Woodsong by Gary Paulsen

Woodsong By Gary Paulsen A Novel Study by Nat Reed Woodsong By Gary Paulsen Table of Contents Suggestions and Expectations ..…………………………….…..………. 3 List of Skills ….……………………………….…………………………….. 4 Synopsis / Author Biography …..………………………………………… 5 Student Checklist …………………………………………………………… 6 Reproducible Student Booklet ..…………………………………………… 7 Answer Key ...………………………………………………………………… 60 About the author: Nat Reed has been a member of the teaching profession for more than 30 years. He is presently a full-time instructor at Trent University in the Teacher Education Program. For more information on his work and literature, please visit the websites www.reedpublications.org and www.novelstudies.org. Copyright © 2013 Nat Reed All rights reserved by author. Permission to copy for single classroom use only. Electronic distribution limited to single classroom use only. Not for public display. 2 Woodsong By Gary Paulsen Suggestions and Expectations This sixty-five page curriculum unit can be used in a variety of ways. Most chapters of the novel study focus on one or two chapters of Woodsong and are comprised of four different activities: • Before You Read • Vocabulary Building • Comprehension Questions • Language and Extension Activities A principal expectation of the unit is that students will develop their skills in reading, writing, listening and oral communication, as well as in reasoning and critical thinking. Links with the Common Core Standards (U.S.) Many of the activities included in this curriculum unit are supported by the Common Core Standards. For instance the Reading Standards for Literature, Grade 5, makes reference to a) determining the meaning of words and phrases. including figurative language; b) explaining how a series of chapters fits together to provide the overall structure; c) compare and contrast two characters; d) determine how characters … respond to challenges; e) drawing inferences from the text; f) determining a theme of a story . -

Zenker, Stephanie F., Ed. Books For

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 415 506 CS 216 144 AUTHOR Stover, Lois T., Ed.; Zenker, Stephanie F., Ed. TITLE Books for You: An Annotated Booklist for Senior High. Thirteenth Edition. NCTE Bibliography Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL. ISBN ISBN-0-8141-0368-5 ISSN ISSN-1051-4740 PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 465p.; For the 1995 edition, see ED 384 916. Foreword by Chris Crutcher. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 03685: $16.95 members, $22.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC19 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescent Literature; Adolescents; Annotated Bibliographies; *Fiction; High School Students; High Schools; *Independent Reading; *Nonfiction; *Reading Interests; *Reading Material Selection; Reading Motivation; Recreational Reading; Thematic Approach IDENTIFIERS Multicultural Materials; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Designed to help teachers, students, and parents identify engaging and insightful books for young adults, this book presents annotations of over 1,400 books published between 1994 and 1996. The book begins with a foreword by young adult author, Chris Crutcher, a former reluctant high school reader, that discusses what books have meant to him. Annotations in the book are grouped by subject into 40 thematic chapters, including "Adventure and Survival"; "Animals and Pets"; "Classics"; "Death and Dying"; "Fantasy"; "Horror"; "Human Rights"; "Poetry and Drama"; "Romance"; "Science Fiction"; "War"; and "Westerns and the Old West." Annotations in the book provide full bibliographic information, a concise summary, notations identifying world literature, multicultural, and easy reading title, and notations about any awards the book has won. -

Quizzes Selected

Quizzes Selected Oakview Elementary, 01/31/12 Guided Book Reading Reading Book Author Lexile Level Level Points "A" Is for Abigail Lynne Cheney 1,030 4.6Q 3 "A" Was Once An Apple Pie Edward Lear 1.8 1 10 For Dinner Jo Ellen Bogart 820 5.0 2 100 Cupboards N. D. Wilson 650 3.7 14 100-Pound Problem, The Jennifer 200 2.4K 2 100th Day Of School (Bader) BonnieDussling Bader 210 2.1L 3 100th Day Of School, The Angela Shelf 340 1.5 1 100th Thing About Caroline LoisMedearis Lowry 690 5.5 6 15 Minutes Steve Young 650 3.5P 9 18th Emergency, The Betsy Byars 750 4.4 6 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea Jules Verne 1,030 8.1 23 26 Fairmount Avenue Tomie dePaola 760 4.8N 3 5,000-Year-Old Puzzle, The Claudia Logan 900 5.9O 3 50 Below Zero Robert Munsch 290 3.1 2 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbin Dr. Seuss 520 3.7 3 512 Ants On Sullivan Street Carol A. Losi 2.5 3 88 Pounds Of Tomatoes Cindy 400 2.9L 3 A. Is For Salad MikeNeuschwander Lester BR 1.8D 1 A. Lincoln And Me Louise Borden 650 2.7M 2 Aani And The Tree Huggers Jeannine Atkins 650 4.2 2 Abby In Wonderland Ann M. Martin 740 5.9 6 Abby Takes A Stand Patricia C. 580 3.0P 5 ABC I Like Me! NancyMcKissack Carlson 190 1.5 1 ABC Mystery Doug Cushman 410 1.9 1 Abe Lincoln Log Cabin-White..