Development Through Hosting the FIFA World Cup Joseph Wenner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FIFA 17 Playstation 3

TARTALOM TELJES IRÁNYÍTÁS 3 CAREER (KARRIERMÓD) 17 A JÁTÉK ELSő iNDÍTÁSA 10 SKILL GAMES JÁTÉKMENET 11 (KÉPESSÉGJÁTÉKOK) 18 FIFA ULTIMATE TEAM (FUT) 13 ONLINE 18 KEZDőRÚGÁS 16 SEGÍTSÉGRE VAN SZÜKSÉGED? 19 2 TELJES IRÁNYÍTÁS V EZÉRLÉS MEGJEGYZÉS: A kézikönyvben írtak a klasszikus vezérlési konfigurációra vonatkoznak. M OZGÁS Játékos mozgatása bal kar Első érintés/Továbbrúgás R gomb + jobb kar Sprint R gomb + bal kar Labda megállítása, kapu felé fordulás bal kar (elengedés) + Q gomb Labdafedezés/Lassú labdavezetés/Lezárás W gomb (hosszan) + bal kar Labdavezetés felnézve W gomb + R gomb Trükkmozdulatok jobb kar Labda megállítása bal kar (elengedés) + R gomb (nyomás) TÁMADÁS (EGYSZERű) Rövid passz/Fejes S gomb Ívelt passz/Beadás/Fejes F gomb Átlövés D gomb (Lövés/Kapáslövés/Fejes) A gomb Nyesett lövés Q gomb + A gomb Trükkös lövés E gomb + A gomb Lapos lövés/Lapos fejelés A gomb + A gomb (röviden) Lövőcsel A gomb, S gomb + bal kar Passz-lövőcsel F gomb, S gomb + bal kar 3 TÁMADÁS (HALADÓ) Labdavédelem (labdavezetés közben) W gomb + bal kar Magas átlövés Q gomb + D gomb Átfűzött nyesett átlövés E gomb + Q gomb + D gomb Pattanó nyesett passz E gomb + F gomb Alacsony beadás F gomb (kétszer röviden) Lapos beadás F gomb (háromszor röviden) Korai átadás Q gomb + F gomb Segítség kérése E gomb (röviden) Színlelt passz E gomb (hosszan) Szuper megszakítás W gomb + R gomb Erős lapos passz E gomb + S gomb Látványos lövés W gomb + A gomb Látványos passz W gomb + S gomb Érintés nélküli kis csel Q gomb + bal kar Érintés nélküli nagy csel Q gomb + R gomb Kézi -

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347 PlayStation 3 Atlus 3D Dot Game Heroes PS3 $16.00 52 722674110402 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Ace Combat: Assault Horizon PS3 $21.00 2 Other 853490002678 PlayStation 3 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars PS3 $14.00 37 Publishers 014633098587 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Alice: Madness Returns PS3 $16.50 60 Aliens Colonial Marines 010086690682 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ (Portuguese) PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines (Spanish) 010086690675 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines Collector's 010086690637 PlayStation 3 Sega $76.00 9 Edition PS3 010086690170 PlayStation 3 Sega Aliens Colonial Marines PS3 $50.00 92 010086690194 PlayStation 3 Sega Alpha Protocol PS3 $14.00 14 047875843479 PlayStation 3 Activision Amazing Spider-Man PS3 $39.00 100+ 010086690545 PlayStation 3 Sega Anarchy Reigns PS3 $24.00 100+ 722674110525 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Armored Core V PS3 $23.00 100+ 014633157147 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Army of Two: The 40th Day PS3 $16.00 61 008888345343 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed II PS3 $15.00 100+ Assassin's Creed III Limited Edition 008888397717 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft $116.00 4 PS3 008888347231 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III PS3 $47.50 100+ 008888343394 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed PS3 $14.00 100+ 008888346258 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood PS3 $16.00 100+ 008888356844 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Revelations PS3 $22.50 100+ 013388340446 PlayStation 3 Capcom Asura's Wrath PS3 $16.00 55 008888345435 -

Decision Adjudicatory Chamber FIFA Ethics Committee

Decision of the adjudicatory chamber of the FIFA Ethics Committee Mr Vassilios Skouris [GRE], Chairman Ms Margarita Echeverria [CRC], Member Mr Melchior Wathelet [BEL], Member taken on 26 July 2019 in the case of: Mr Ricardo Teixeira [BRA] Adj. ref. no. 14/2019 (Ethics 150972) I. Inferred from the file 1. Mr Ricardo Teixeira (hereinafter “Mr Teixeira” or “the official”), Brazilian national, has been a high-ranking football official since 1989, most notably the president of the Confederação Brasileira de Futebol (CBF) from 1989 until 2012. He was a mem- ber of the FIFA Executive Committee from 1994 until 2012 and a member of the CONMEBOL Executive Committee. Additionally, he was a member of several stand- ing committees of FIFA, such as the Organising Committee for the FIFA Confedera- tions CupTM, Organising Committee for the FIFA World CupTM, Referees Committee, Marketing and TV Committee, Futsal and Beach Soccer Committee, Ethics Commit- tee and Committee for Club Football. 2. On 27 May 2015, the United States Department of Justice (hereinafter “DOJ”) is- sued a press release relating to the Indictment of the United States District Court, Eastern District of New York also dated 27 May 2015 (hereinafter “the Indictment”). In the Indictment, the DOJ charged several international football executives with “racketeering, wire fraud and money laundering conspiracies, among other of- fenses, in connection with their participation in a twenty-four-year scheme to enrich themselves through the corruption of international soccer”. The Indictment was fol- lowed by arrests of various persons accused therein, executed by state authorities in Europe, South America and the United States of America. -

FIFA -17 World Cup Brochure

White Paper: An Introduction to Hosted By India • Viewership: The U-17 world cup will draw • Youth Development: The lead up to the upon a global audience due to many main event will ensure concerted efforts participating nations from different to develop the grassroots projects continents which will lead to high TV leading to the creation of a talent pool of viewership. MSM India (Sony Six) is the players. It will also benefit the coaches broadcasting partner of this event and who play an integral part in the holistic will telecast live matches in 2017. development of players. Many youth competitions will also take place to scout • Sponsorship: Revenue opportunities are talented players. Overall, youth also possible through partnerships with development programs will receive a national supporters. National supporters massive boost. are sponsors with roots in the host country to promote an association in • National Pride: This event has the domestic market. For e.g. FIFA U-17 capacity to improve the image of the World Cup in UAE last year had 8 country as a sporting nation. India can national supporters (Abu Dhabi tourism, also prove that they are capable of Abu Dhabi airport, ADNOC, EMAAR, successfully planning and executing a Etisalat, First Gulf Bank, Fifa.com and global sporting event of this magnitude Football for Hope) and gain international recognition. • Football Infrastructure: One of the • Knowledge transfer: Hosting a FIFA important benefits is infrastructure event is a good way to understand state- upgrading and renovation of proposed of-the-art know-how, learn the latest stadium and training sites. -

The 2006 FIFA World Cup™ and Its Effect on the Image and Economy of Germany HOW the GERMAN POPULATION SAW IT

www.germany-tourism.de ”A time to make friends™“ The 2006 FIFA World Cup™ and its effect on the image and economy of Germany HOW THE GERMAN POPULATION SAW IT Before the 2006 FIFA World Cup™ took place, 81.7 per cent of people in How much of the World Cup atmosphere could Germany thought the country was the right choice to host the event. they already sense in Germany? What impact did they expect it to have on their own town or city? 70% 35% 60% 30% 32% 50% 58% 25% 29% 51% 40% 20% 30% 37% 15% 36% 20% 10% 18% 10% 5% 10% 10% 4% 0% 2% 3% 8% 0% Increased/improved a great deal Awareness Tourism quite a lot Image Infrastrucutre some Revenue Events not much Jobs No increase/improvement none at all Source: Prof. Alfons Madeja – Source: Prof. Alfons Madeja – Survey of Germans at the 2005 FIFA Confederation Cup in Germany Survey of Germans taken at the 2005 FIFA Confederation Cup in Germany INVESTMENT AND OPPORTUNITY The impact of foreign visitors to Germany Scenario in billion euros 2006 2007 2008 Total Economic impact of the 2006 FIFA World Cup™ The German government estimates the overall value to the economy Gross domestic product 1.25 0.37 0.03 1,65 of which consumer spending 0.52 0.39 0.07 0.98 of World Cup-induced activity to be around three billion euros, spre- Capital investment 0.13 0.05 -0.04 0.14 ad over a period of at least three years. The event is predicted to crea- Exports 1.02 0.04 0.01 1.07 te 50,000 new jobs, which are expected to generate additional eco- Imports 0.42 0.11 0.00 0.53 nomic value of about 1.5 billion euros in 2007 and 2008, and to Tax revenue 2.32 0.58 0.04 2.94 increase tax receipts by around 600 million euros." Steueraufkommen 0.286 0.089 0.013 0.388 Workforce 14,539 47 1,180 15,766 Source: seventh progress report by the German federal government in preparation for the 2006 FIFA World Cup™ Source: GNTB, GWS, Nov. -

Qatar 2022™ Sustainability Strategy 3

Sustainability Strategy 1 FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022TM Sustainability strategy 2 FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022™ Sustainability Strategy 3 Contents Foreword by the FIFA Secretary General 4 Foreword by the Chairman of the FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022 LLC and Secretary General of the Supreme Committee for Delivery & Legacy 6 Introduction 8 The strategy at a glance 18 Human pillar 24 Social pillar 40 Economic pillar 56 Environmental pillar 64 Governance pillar 78 Alignment with the UN Sustainable Development Goals 88 Annexe 1: Glossary 94 Annexe 2: Material topic definitions and boundaries 98 Annexe 3: Salient human rights issues covered by the strategy 103 Annexe 4: FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022™ Sustainability Policy 106 4 FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022™ Sustainability Strategy 5 Foreword © Getty Images by the FIFA Secretary General Sport, and football in particular, has a unique capacity The implementation of the FIFA World Cup Qatar We are also committed to delivering an inclusive As a former long-serving UN official, I firmly believe to inspire and spark the passion of millions of fans 2022™ Sustainability Strategy will be a central FIFA World Cup 2022™ tournament experience that in the power of sport, and of football in particular, around the globe. As the governing body of element of our work to realise these commitments is welcoming, safe and accessible to all participants, to serve as an enabler for the SDGs, and I am football, we at FIFA have both a responsibility and over the course of the next three years as we attendees and communities in Qatar and around personally committed to seeing FIFA take a leading a unique opportunity to harness the power of the prepare to proudly host the FIFA World Cup™ in the world. -

Economic Impacts of the FIFA World Cup in Developing Countries

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Honors Theses Lee Honors College 4-17-2015 Economic Impacts of the FIFA World Cup in Developing Countries Mirele Matsuoka De Aragao Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses Part of the Economic Theory Commons, Public Economics Commons, and the Regional Economics Commons Recommended Citation Matsuoka De Aragao, Mirele, "Economic Impacts of the FIFA World Cup in Developing Countries" (2015). Honors Theses. 2609. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses/2609 This Honors Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Lee Honors College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ECONOMIC IMPACTS OF FIFA WORLD CUP IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES by Mirele Mitie Matsuoka de Aragão A thesis submitted to Lee Honors College Western Michigan University April 2015 Thesis Committee: Sisay Asefa, Ph.D., Chair Donald Meyer, Ph.D. Donald L. Alexander, Ph.D. ECONOMIC IMPACTS OF FIFA WORLD CUP 2 Table of Contents I. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 3 II. Comparing South Africa and Brazil ............................................................................ 4 III. Effects in South Africa............................................................................................ -

Finanzas-2020-En.Pdf

ÍNDICETABLE OF DE CONTENTS CONTENIDOS FINANCIAL REPORT 2020 BUDGET 2021 [06] LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT OF CONMEBOL [46] ESTIMATED 2021 STATEMENT OF INCOME AND EXPENDITURES [08] LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT OF THE FINANCIAL COMMISSION [48] 2021 BUDGET FOR PLANNED INVESTMENTS [10] SUMMARY OF THE YEAR 2020 [49] DIRECT INVESTMENT IN FOOTBALL 2021 [12] OPINION FROM PWC INDEPENDENT AUDITORS ON THE [49] EVOLUTION OF CLUB TOURNAMENT PRIZES 01 [50] EVOLUTION OF INVESTMENT IN FOOTBALL 2016-2021 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS AS OF DECEMBER 31, 2020 02 [14] BALANCE SHEET AS OF DECEMBER 31, 2020 [52] CONTRIBUTIONS BY TOURNAMENTS TO CLUBS BY CONMEBOL [15] STATEMENT OF INCOME AND EXPENDITURES AS OF LIBERTADORES, COMPARING YEARS 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020 DECEMBER 31, 2020 AND 2021 [16] STATEMENT OF CHANGES IN EQUITY AS OF DECEMBER 31, 2020 [53] CONTRIBUTIONS BY TOURNAMENTS TO CLUBS BY CONMEBOL [17] CASH FLOW STATEMENT SUDAMERICANA, COMPARING YEARS 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020 [18] NOTES TO THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS AND 2021 [40] INTERNAL AUDIT REPORT [54] CONTRIBUTIONS BY TOURNAMENTS TO CLUBS BY CONMEBOL [42] CERTIFICATES OF COMPLIANCE RECOPA, COMPARING YEARS 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020 AND 2021 [56] COMMISSION OF COMPLIANCE AND AUDITING REPORT [57] FINANCIAL COMMISSION REPORT 2020 2020 l l FINANCIAL REPORT FINANCIAL FINANCIAL REPORT FINANCIAL 2 3 FINANCIAL REPORT 2020 [06] LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT OF CONMEBOL [08] LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT OF THE FINANCIAL COMMISSION [10] SUMMARY OF THE YEAR 2020 [12] OPINION FROM PWC INDEPENDENT AUDITORS ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS AS OF DECEMBER 31, 2020 [14] BALANCE SHEET AS OF DECEMBER 31, 2020 [15] STATEMENT OF INCOME AND EXPENDITURES AS OF DECEMBER 31, 2020 [16] STATEMENT OF CHANGES IN EQUITY AS OF DECEMBER 31, 2020 [17] CASH FLOW STATEMENT 01[18] NOTES TO THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS [40] INTERNAL AUDIT REPORT [42] CERTIFICATES OF COMPLIANCE Dear South American because it speaks for CONMEBOL’s seriousness and football family; responsibility, as well as the very positive image it projects. -

Football for Hope Forum 13-Year-Old Into a Hard-Headed 2017 Goalkeeper

July 2017 FOOTBALLTHE Quarterly MAGAZINE OF STREETFOOTBALLWORLD4 GOOD SPOTLIGHT THE FOOTBALL IN FOCUS FOR HOPE HIGH-FLYING FOOTBALL FOR GOOD FORUM 2017 IN NEPAL WHAT IS THE CONTRIBUTION OF FOOTBALL TO THE UN SUSTAINABLE Join us on our journey discovering football for good in Kathmandu DEVELOPMENT GOALS? and Bhaktapur p. 6 p. 30 FOOTBALL4GOOD TALKS NETWORK MEMBERS’ STORIES FIFA SECRETARY GENERAL FATMA SAMOURA A RAYAN OF HOPE Speaks about football for good with Jürgen How football turned a timid Griesbeck during the Football for Hope Forum 13-year-old into a hard-headed 2017 goalkeeper. And a very wishful thinker. p. 16 p. 50 www.streetfootballworld.org ABOUT FOOTBALL FOR GOOD & THE UN SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS I was at the beginning of my career when the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) were established. For 15 years, they followed me and I followed them. In early 2016, the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development officially came into force. Over the next fifteen years, with these new goals that universally apply to all, the 193 United Nations member states have pledged to mobilise efforts to end all forms of poverty, fight inequalities and tackle climate change, while ensuring that no one is left behind. The members of the streetfootballworld network, and many more friends and fellows across the globe, have intrinsically adopted such an attitude already during the establishment of their organisations. In fact, the very reason they initiated their programmes in the Mathare Valley, the streets of Dublin or the favelas of Rio was because governments had failed to address the needs of those on the margins of society. -

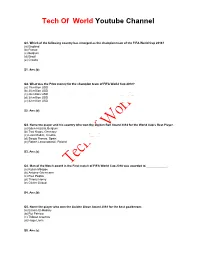

Tech of World Youtube Channel

Tech Of World Youtube Channel Q1. Which of the following country has emerged as the champion team of the FIFA World Cup 2018? (a) England (b) France (c) Belgium (d) Brazil (e) Croatia S1. Ans.(b) Q2. What was the Prize money for the champion team of FIFA World Cup 2018? (a) 15 million USD (b) 20 million USD (c) 26 million USD (d) 38 million USD (e) 42 million USD S2. Ans.(d) Q3. Name the player and his country who won the Golden Ball Award 2018 for the World Cup's Best Player. (a) Eden Hazard, Belgium (b) Toni Kroos, Germany (c) Luka Modric, Croatia (d) Sergio Ramos, Spain (e) Robert Lewandowski, Poland S3. Ans.(c) Q4. Man of the Match award in the Final match of FIFA World Cup 2018 was awarded to _____________. (a) Kylian Mbappe (b) Antoine Griezmann (c) Paul Pogba (d) Thierry Henry (e) Olivier Giroud S4. Ans.(b) Q5. Name the player who won the Golden Glove Award 2018 for the best goalkeeper. (a) Essam El-Hadary (b) Rui Patricio (c) Thibaut Courtois (d) Hugo Lloris S5. Ans.(c) Q6. What was the official mascot of the 2018 FIFA World Cup? (a) Caira (b) Koara (c) Zabivaka (d) Zaltanowa (e) Somarova S6. Ans.(c) Q7. Which of the following footballer has won the Golden Boot Award in FIFA World Cup 2018? (a) Luka Modric (b) Leonel Messi (c) Cristiano Ronaldo (d) Kylian Mbappe (e) Harry Kane S7. Ans.(e) Q8. The official song of the tournament was ‘__________’ with vocals from Will Smith, Nicky Jam and Era Istrefi. -

The Impact of FIFA World Cup on Sponsoring Companies and the Host Country Stock Market Index

The Impact of FIFA World Cup on Sponsoring Companies and the Host Country Stock Market Index MASTER THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 15 PROGRAMME OF STUDY: International Financial Analysis AUTHOR: Anas Alsaadi & Sayan Banerjee JÖNKÖPING May 2020 Master Thesis in Business Administration Title: The Impact of FIFA World Cup on Sponsoring Companies and the Host Country Stock Market Index Authors: Anas Alsaadi & Sayan Banerjee Tutor: Michael Olsson Date: 2020-05-18 Abstract We investigate if the FIFA affects the sponsoring companies’ stock returns more than that of the host countries’ securities indices, we have presented the findings of earlier research entities and provided some insight into the influence of FIFA and other sports on global stock index. We have also made a detailed consideration of stock market reaction for the sponsoring companies’ securities and host countries’ security indices and found some articles about country wise investor sentiment based on match outcomes because they are the one to invest in the sponsoring companies or the host country security markets. Throughout our work we have tried to verify our hypothesis and support it with year-wise and host country-wise data through regression models and an event study. In the end, we have tried to come up with coherent findings based on the proven hypothesis and discuss their interpretations along with some possible predictions for the upcoming FIFA world cup in 2022. i Contents 1 Introduction ........................................................................... 1 2 Theory..................................................................................... 2 2.1 Findings of Goldman Sachs ................................................................... 2 2.2 An Insight to Investor Behaviour and Their Consequent Investment Decisions That Affect the Stock Market ................................................ -

FIFA World Cup™ Is fi Nally Here!

June/July 2010 SPECIAL DOUBLE ISSUE | Team profi les | Star players | National hopes | South Africa’s long journey | Leaving a legacy | Broadcast innovations | From Montevideo to Johannesburg | Meet the referees | Team nicknames TIME FOR AFRICA The 2010 FIFA World Cup™ is fi nally here! EDITORIAL CELEBRATING HUMANITY Dear members of the FIFA family, Finally it has arrived. Not only is the four-year wait for the next FIFA World Cup™ almost over, but at last the world is getting ready to enjoy the fi rst such tournament to be played on African soil. Six years ago, when we took our most prestigious competition to Africa, there was plenty of joy and anticipation on the African continent. But almost inevitably, there was also doubt and scepticism from many parts of the world. Those of us who know Africa much better can share in the continent’s pride, now that South Africa is waiting with its famed warmth and hospitality for the imminent arrival of the world’s “South Africa is best teams and their supporters. I am convinced that the unique setting of this year’s tournament will make it one of the most waiting with its memorable FIFA World Cups. famed warmth and Of course we will also see thrilling and exciting football. But the fi rst-ever African World Cup will always be about more than just hospitality, and I am the game. In this bumper double issue of FIFA World, you will fi nd plenty of information on the competition itself, the major stars convinced that the and their dreams of lifting our famous trophy in Johannesburg’s unique setting of this spectacular Soccer City on 11 July.