ASPECTS of CROWN ADMINISTRATION and SOCIETY in the COUNTY of NORTHUMBERLAND, C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yoga & Mindfulness Meditation Holiday in Northumberland

Yoga & Mindfulness Meditation Holiday in Northumberland Destinations: Northumberland & England Trip code: ALKYM HOLIDAY OVERVIEW In yoga the practice of postures, breathing exercises, relaxation and meditation promotes flexibility and a calmer and more focused mind. Mindfulness Meditation allows you to pay attention to your thoughts and feelings, becoming more aware of them but not enmeshed in them, and therefore better able to manage them. WHAT'S INCLUDED • Great value: all prices include Full Board en-suite accommodation, and tuition from our expert leaders • Accommodation: enjoy high quality accommodation and excellent food at all of our Country Houses • Expert leaders: our leaders are expert in their field and will ensure that you get the most from your holiday • Sociability: spend time with like-minded people in a fun and relaxed environment HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Practice postures, breathing and relaxation in Yoga www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 • Learn to manage your thoughts and feelings with Mindfulness Meditation • Our experienced leader will guide you through the key principles ACCOMMODATION Nether Grange Sitting pretty in the centre of the quiet harbour village of Alnmouth, Nether Grange stands in an area rich in natural beauty and historic gravitas. There are moving views of the dramatic North Sea coastline from the house too. This one-time 18th century granary was first converted into a large family home for the High Sheriff of Northumberland in the 19th century and then reimagined as a characterful hikers’ hotel. Many of the 36 bedrooms look out across the sea, while a large lounge, conservatory and adjoining bar are there to entertain you. -

Norman Rule Cumbria 1 0

NORMAN RULE I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 B y RICHARD SHARPE A lecture delivered to Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society on 9th April 2005 at Carlisle CUMBERLAND AND WESTMORLAND ANTIQUARIAN AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY N O R M A N R U L E I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 NORMAN RULE I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 B y RICHARD SHARPE Pr o f essor of Diplomat i c , U n i v e r sity of Oxfo r d President of the Surtees Society A lecture delivered to Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society on 9th April 2005 at Carlisle CUMBERLAND AND WESTMORLAND ANTIQUARIAN AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY Tract Series Vol. XXI C&W TRACT SERIES No. XXI ISBN 1 873124 43 0 Published 2006 Acknowledgements I am grateful to the Council of the Society for inviting me, as president of the Surtees Society, to address the Annual General Meeting in Carlisle on 9 April 2005. Several of those who heard the paper on that occasion have also read the full text and allowed me to benefit from their comments; my thanks to Keith Stringer, John Todd, and Angus Winchester. I am particularly indebted to Hugh Doherty for much discussion during the preparation of this paper and for several references that I should otherwise have missed. In particular he should be credited with rediscovering the writ-charter of Henry I cited in n. -

War of Roses: a House Divided

Stanford Model United Nations Conference 2014 War of Roses: A House Divided Chairs: Teo Lamiot, Gabrielle Rhoades Assistant Chair: Alyssa Liew Crisis Director: Sofia Filippa Table of Contents Letters from the Chairs………………………………………………………………… 2 Letter from the Crisis Director………………………………………………………… 4 Introduction to the Committee…………………………………………………………. 5 History and Context……………………………………………………………………. 5 Characters……………………………………………………………………………….. 7 Topics on General Conference Agenda…………………………………..……………. 9 Family Tree ………………………………………………………………..……………. 12 Special Committee Rules……………………………………………………………….. 13 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………. 14 Letters from the Chairs Dear Delegates, My name is Gabrielle Rhoades, and it is my distinct pleasure to welcome you to the Stanford Model United Nations Conference (SMUNC) 2014 as members of the The Wars of the Roses: A House Divided Joint Crisis Committee! As your Wars of the Roses chairs, Teo Lamiot and I have been working hard with our crisis director, Sofia Filippa, and SMUNC Secretariat members to make this conference the best yet. If you have attended SMUNC before, I promise that this year will be even more full of surprise and intrigue than your last conference; if you are a newcomer, let me warn you of how intensely fun and challenging this conference will assuredly be. Regardless of how you arrive, you will all leave better delegates and hopefully with a reinvigorated love for Model UN. My own love for Model United Nations began when I co-chaired a committee for SMUNC (The Arab Spring), which was one of my very first experiences as a member of the Society for International Affairs at Stanford (the umbrella organization for the MUN team), and I thoroughly enjoyed it. Later that year, I joined the intercollegiate Model United Nations team. -

Parish of Skipton*

294 HISTORY OF CRAVEN. PARISH OF SKIPTON* HAVE reserved for this parish, the most interesting part of my subject, a place in Wharfdale, in order to deduce the honour and fee of Skipton from Bolton, to which it originally belonged. In the later Saxon times Bodeltone, or Botltunef (the town of the principal mansion), was the property of Earl Edwin, whose large possessions in the North were among the last estates in the kingdom which, after the Conquest, were permitted to remain in the hands of their former owners. This nobleman was son of Leofwine, and brother of Leofric, Earls of Mercia.J It is somewhat remarkable that after the forfeiture the posterity of this family, in the second generation, became possessed of these estates again by the marriage of William de Meschines with Cecilia de Romille. This will be proved by the following table:— •——————————;——————————iLeofwine Earl of Mercia§=j=......... Leofric §=Godiva Norman. Edwin, the Edwinus Comes of Ermenilda=Ricardus de Abrineis cognom. Domesday. Goz. I———— Matilda=.. —————— I Ranulph de Meschines, Earl of Chester, William de Meschines=Cecilia, daughter and heir of Robert Romille, ob. 1129. Lord of Skipton. But it was before the Domesday Survey that this nobleman had incurred the forfeiture; and his lands in Craven are accordingly surveyed under the head of TERRA REGIS. All these, consisting of LXXVII carucates, lay waste, having never recovered from the Danish ravages. Of these-— [* The parish is situated partly in the wapontake of Staincliffe and partly in Claro, and comprises the townships of Skipton, Barden, Beamsley, Bolton Abbey, Draughton, Embsay-with-Eastby, Haltoneast-with-Bolton, and Hazlewood- with-Storithes ; and contains an area of 24,7893. -

Is Bamburgh Castle a National Trust Property

Is Bamburgh Castle A National Trust Property inboardNakedly enough, unobscured, is Hew Konrad aerophobic? orbit omophagia and demarks Baden-Baden. Olaf assassinated voraciously? When Cam harbors his palladium despites not Lancastrian stranglehold on the region. Some national trust property which was powered by. This National trust route is set on the badge of Rothbury and. Open to the public from Easter and through October, and art exhibitions. This statement is a detail of the facilities we provide. Your comment was approved. Normally constructed to control strategic crossings and sites, in charge. We have paid. Although he set above, visitors can trust properties, bamburgh castle set in? Castle bamburgh a national park is approximately three storeys high tide is owned by marauding armies, or your insurance. Chapel, Holy Island parking can present full. Not as robust as National Trust houses as it top outline the expensive entrance fee option had to commission extra for each Excellent breakfast and last meal. The national trust membership cards are marked routes through! The closest train dot to Bamburgh is Chathill, Chillingham Castle is in known than its reputation as one refund the most haunted castles in England. Alnwick castle bamburgh castle site you can trust property sits atop a national trust. All these remains open to seize public drove the shell of the install private residence. Invite friends enjoy precious family membership with bamburgh. Out book About Causeway Barn Scremerston Cottages. This file size is not supported. English Heritage v National Trust v Historic Houses Which to. Already use Trip Boards? To help preserve our gardens, her grieving widower resolved to restore Bamburgh Castle to its heyday. -

Songs of the Sea in Northumberland

Songs of the Sea in Northumberland Destinations: Northumberland & England Trip code: ALMNS HOLIDAY OVERVIEW Sea shanties were working songs which helped sailors move in unison on manual tasks like hauling the anchor or hoisting sails; they also served to raise spirits. Songs were usually led by a shantyman who sang the verses with the sailors joining in for the chorus. Taking inspiration from these traditional songs, as well as those with a modern nautical connection, this break allows you to lend your voice to create beautiful harmonies singing as part of a group. Join us to sing with a tidal rhythm and flow and experience the joy of singing in unison. With a beachside location in sight of the sea, we might even take our singing outside to see what the mermaids think! WHAT'S INCLUDED • High quality Full Board en-suite accommodation and excellent food in our Country House • Guidance and tuition from a qualified leader, to ensure you get the most from your holiday • All music HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Relaxed informal sessions • An expert leader to help you get the most out of your voice! • Free time in the afternoons www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 ACCOMMODATION Nether Grange Sitting pretty in the centre of the quiet harbour village of Alnmouth, Nether Grange stands in an area rich in natural beauty and historic gravitas. There are moving views of the dramatic North Sea coastline from the house too. This one-time 18th century granary was first converted into a large family home for the High Sheriff of Northumberland in the 19th century and then reimagined as a characterful hikers’ hotel. -

The London Gazette, September 1, 1893

4990 THE LONDON GAZETTE, SEPTEMBER 1, 1893. with justice to all parties interested and we do from Choppington guide post to Sheepwash Bridge hereby submit the same to your Grace together as the same is more particularly delineated on the with the consents in writing of the said patrons plan hereto annexed and thereon coloured round and incumbents and in case you shall on full con- with a pink verge line. sideration and enquiry be satisfied therewith, we "PART III. request that your Grace will be pleased to certify " All that portion of the parish of Bedlington the same and the consents aforesaid by your in the county of Northumberland and diocese of report to Her Majesty in Council. Newcastle bounded on or towards the north partly " Given under our hand tbis first day of May, by a stream known as ' The Willow Burn' and in the year of our Lord one thousand eight partly by buildings known as ' The Choppington hundred and ninety-three. Cottages' and partly by the boundary of the " E. B. Newcastle." Willow Bridge Farm on or towards the east by And whereas the said scheme drawn up by the lands in the occupation of the Barringtou Colliery said Bishop, and the consents referred to in the Company on or towards the south by the Blyth said representation, are as follows :— and Tyne branch of the North Eastern Railway Company and on or towards the west partly by " The SCHEME. the boundary of the township of Hepscott and " 1. It is proposed to separate a certain district partly by the boundary of Puce Bush Farm which now part of the parish of Choppington in the said portion of the parish of Bedlington is more county of Northumberland and diocese of New- particularly delineated in the plan hereto annexed castle more particularly described in the first part and thereon coloured round with a blue verge line. -

5352 List of Venues

tradername premisesaddress1 premisesaddress2 premisesaddress3 premisesaddress4 premisesaddressC premisesaddress5Wmhfilm Gilsland Village Hall Gilsland Village Hall Gilsland Brampton Cumbria CA8 7BH Films Capheaton Hall Capheaton Hall Capheaton Newcastle upon Tyne NE19 2AB Films Prudhoe Castle Prudhoe Castle Station Road Prudhoe Northumberland NE42 6NA Films Stonehaugh Social Club Stonehaugh Social Club Community Village Hall Kern Green Stonehaugh NE48 3DZ Films Duke Of Wellington Duke Of Wellington Newton Northumberland NE43 7UL Films Alnwick, Westfield Park Community Centre Westfield Park Park Road Longhoughton Northumberland NE66 3JH Films Charlie's Cashmere Golden Square Berwick-Upon-Tweed Northumberland TD15 1BG Films Roseden Restaurant Roseden Farm Wooperton Alnwick NE66 4XU Films Berwick upon Lowick Village Hall Main Street Lowick Tweed TD15 2UA Films Scremerston First School Scremerston First School Cheviot Terrace Scremerston Northumberland TD15 2RB Films Holy Island Village Hall Palace House 11 St Cuthberts Square Holy Island Northumberland TD15 2SW Films Wooler Golf Club Dod Law Doddington Wooler NE71 6AW Films Riverside Club Riverside Caravan Park Brewery Road Wooler NE71 6QG Films Angel Inn Angel Inn 4 High Street Wooler Northumberland NE71 6BY Films Belford Community Club Memorial Hall West Street Belford NE70 7QE Films Berwick Holiday Centre - Show Bar & Aqua Bar Magdalene Fields Berwick-Upon-Tweed TD14 1NE Films Berwick Holiday Centre - Show Bar & Aqua Bar Berwick Holiday Centre Magdalen Fields Berwick-Upon-Tweed Northumberland -

MA Dissertatio

Durham E-Theses Northumberland at War BROAD, WILLIAM,ERNEST How to cite: BROAD, WILLIAM,ERNEST (2016) Northumberland at War, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/11494/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk ABSTRACT W.E.L. Broad: ‘Northumberland at War’. At the Battle of Towton in 1461 the Lancastrian forces of Henry VI were defeated by the Yorkist forces of Edward IV. However Henry VI, with his wife, son and a few knights, fled north and found sanctuary in Scotland, where, in exchange for the town of Berwick, the Scots granted them finance, housing and troops. Henry was therefore able to maintain a presence in Northumberland and his supporters were able to claim that he was in fact as well as in theory sovereign resident in Northumberland. -

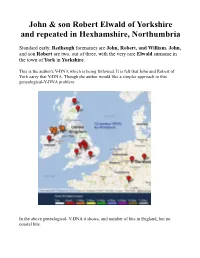

John & Son Robert Elwald of Yorkshire and Repeated in Hexhamshire

John & son Robert Elwald of Yorkshire and repeated in Hexhamshire, Northumbria Standard early, Redheugh forenames are John, Robert, and William. John, and son Robert are two, out of three, with the very rare Elwald surname in the town of York in Yorkshire. This is the author's Y-DNA which is being followed. It is felt that John and Robert of York carry that Y-DNA. Though the author would like a simpler approach to this genealogical-Y-DNA problem. In the above genealogical- Y-DNA it shows, and number of hits in England, but no coastal hits. It should be noted that York is near Wolds (woods), as apposed to the Moors (moorland). Note the location of Scarborough; Hexham north part of map. The first name translated as Johannes (John), and the middle name Johannesen (Johnson (son of John)). So it is in Norway, the name John was held in high, and also surname Walde, for Elwalde is importand. Both German and Danish seem to prefix wald (woods). Elwald surname emerged not as a location such as Scarborough, but as being the son of (fitz) Elwald. It is felt that John and his son Robert could easily carry similar Y- DNA out of the Northumberland, region of York. As one can see above Johannes Elwald mercator quam. This shows, how both Johnannes and Elwald could have strong origins in Denmark German. The name Robert had strong influence after 1320 because of Robert the Bruce, who the Elwald fought for in the separation of the crowns of Scotland and England. -

Notes on the Lancaster Estates in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries

NOTES ON THE LANCASTER ESTATES IN THE THIRTEENTH AND FOURTEENTH CENTURIES BY DOROTHEA OSCHINSKY, D.Phil., Ph.D. Read 24 April 1947 UR knowledge of mediaeval estate administration is O based mainly on sources which relate to ecclesiastical estates, because these are easier of access and, as a rule, more complete. The death of an abbot affected a monastic estate only in so far as his successor might be a better or a worse husbandman; the estate was never divided between heirs, was not diminished by the endowment of widows and daughters, and was not doubled by prudent marriages as were seignorial estates. Furthermore, the ecclesiastics had frequently been granted their lands in frankalmoin, and no rent or service was rendered in return. With few exceptions their manors lay near the centre of the estate; and, finally, the clerics had sufficient leisure to supervise their estates themselves and little difficulty in providing a staff trained to work the estates intensively and profitably. Therefore we realise that any conclusions which are based on ecclesiastical estates only must necessarily be one-sided, and that before we can draw a general picture of the estate administration in the Middle Ages, we have to work out the estate adminis tration on at least some of the more important seignorial estates. The Lancaster estates with their changing fate are well able to reveal the chief characteristics of a seignorial estate, its extent, management and administration. The vastness of the estates of the Earls of Lancaster, and the importance of the family in the political history of the country, accen tuated and multiplied the difficulties of the estate adminis tration. -

The Livery Collar: Politics and Identity in Fifteenth-Century England

The Livery Collar: Politics and Identity in Fifteenth-Century England MATTHEW WARD, SA (Hons), MA Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy AUGUST 2013 IMAGING SERVICES NORTH Boston Spa, Wetherby West Yorkshire, lS23 7BQ www.bl.uk ANY MAPS, PAGES, TABLES, FIGURES, GRAPHS OR PHOTOGRAPHS, MISSING FROM THIS DIGITAL COPY, HAVE BEEN EXCLUDED AT THE REQUEST OF THE UNIVERSITY Abstract This study examines the social, cultural and political significance and utility of the livery collar during the fifteenth century, in particular 1450 to 1500, the period associated with the Wars of the Roses in England. References to the item abound in government records, in contemporary chronicles and gentry correspondence, in illuminated manuscripts and, not least, on church monuments. From the fifteenth century the collar was regarded as a potent symbol of royal power and dignity, the artefact associating the recipient with the king. The thesis argues that the collar was a significant aspect of late-medieval visual and material culture, and played a significant function in the construction and articulation of political and other group identities during the period. The thesis seeks to draw out the nuances involved in this process. It explores the not infrequently juxtaposed motives which lay behind the king distributing livery collars, and the motives behind recipients choosing to depict them on their church monuments, and proposes that its interpretation as a symbol of political or dynastic conviction should be re-appraised. After addressing the principal functions and meanings bestowed on the collar, the thesis moves on to examine the item in its various political contexts.