World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Choosing the Proper Short Cut Fiber for Your Nonwoven Web

Choosing The Proper Short Cut Fiber for Your Nonwoven Web ABSTRACT You have decided that your web needs a synthetic fiber. There are three important factors that have to be considered: generic type, diameter, and length. In order to make the right choice, it is important to know the chemical and physical characteristics of the numerous man-made fibers, and to understand what is meant by terms such as denier and denier per filament (dpf). PROPERTIES Denier Denier is a property that varies depending on the fiber type. It is defined as the weight in grams of 9,000 meters of fiber. The current standard of denier is 0.05 grams per 450 meters. Yarn is usually made up of numerous filaments. The denier of the yarn divided by its number of filaments is the denier per filament (dpf). Thus, denier per filament is a method of expressing the diameter of a fiber. Obviously, the smaller the denier per filament, the more filaments there are in the yarn. If a fairly closed, tight web is desired, then lower dpf fibers (1.5 or 3.0) are preferred. On the other hand, if high porosity is desired in the web, a larger dpf fiber - perhaps 6.0 or 12.0 - should be chosen. Here are the formulas for converting denier into microns, mils, or decitex: Diameter in microns = 11.89 x (denier / density in grams per milliliter)½ Diameter in mils = diameter in microns x .03937 Decitex = denier x 1.1 The following chart may be helpful. Our stock fibers are listed along with their density and the diameter in denier, micron, mils, and decitex for each: Diameter Generic Type -

Performance Evaluation of 3-D Basalt Fiber Reinforced Concrete & Basalt

Highway IDEA Program Performance Evaluation of 3-D Basalt Fiber Reinforced Concrete & Basalt Rod Reinforced Concrete Final Report for Highway IDEA Project 45 Prepared by: V Ramakrishnan and Neeraj S. Tolmare, South Dakota School of Mines & Technology, Rapid City, SD Vladimir B. Brik, Research & Technology, Inc., Madison, WI November 1998 IDEA PROGRAM F'INAL REPORT Contract No. NCHRP-45 IDEA Program Transportation Resea¡ch Board National Research Council November 1998 PERFORMANCE EVALUATION OF 3.I) BASALT ITIBER REINFORCED CONCRETE & BASALT R:D RETNFORCED CONCRETE V. Rarnalaishnan Neeraj S. Tolmare South Dakota School of Mines & Technolory, Rapid City, SD Principal Investigator: Madimir B. Brik Research & Technology, lnc., Madison, WI INNOVATIONS DESERVING EXPLORATORY ANALYSIS (IDEA) PROGRAMS MANAGED BY THE TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH BOARD (TRB) This NCHRP-IDEA investigation was completed as part of the National Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCHRP). The NCHRP-IDEA program is one of the four IDEA programs managed by the Transportation Research Board (TRB) to foster innovations in highway and intermodal surface transportation systems. The other three IDEA program areas are Transit-IDEA, which focuses on products and results for transit practice, in support of the Transit Cooperative Research Program (TCRP), Safety-IDEA, which focuses on motor carrier safety practice, in support of the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration and Federal Railroad Administration, and High Speed Rail-IDEA (HSR), which focuses on products and results for high speed rail practice, in support of the Federal Railroad Administration. The four IDEA program areas are integrated to promote the development and testing of nontraditional and innovative concepts, methods, and technologies for surface transportation systems. -

New Hemp-Based Fiber Enhances Wet-Mix Shotcrete Performance

New Hemp-Based Fiber Enhances Wet-Mix Shotcrete Performance By Dudley R. (Rusty) Morgan, Lihe (John) Zhang, and Mike Pildysh n innovative processed natural hemp-based fiber without any fibers and mixtures with a synthetic (polypro- has been developed for use in concrete and shot- pylene) microfiber. These studies, conducted in Vancouver, A crete (wet- and dry-mix shotcrete processes) in lieu BC, Canada, demonstrated that when used at equivalent of conventional synthetic fibers, which are derived from fiber-volume addition rates, not only was the natural hemp- hydro-carbon (oil and/or gas) feedstock. A driving force based fiber more effective in mitigating plastic shrinkage behind this development has been the desire to produce cracking than synthetic microfiber but it also provided many a truly sustainable green fiber with dramatic reductions in additional benefits in the plastic and hardened concretes. This was particularly true for the wet-mix shotcrete process, CO2 emissions into the atmosphere during fiber production, compared to the synthetic (mainly polypropylene) fibers cur- where some marked benefits to the shotcrete application rently being used in the concrete and shotcrete industries. and finishing processes were found. Synthetic microfibers have mainly been used in concrete This article provides a summary of the findings from and shotcrete to help mitigate early-age plastic shrinkage the wet-mix shotcrete laboratory study. It also provides cracking. In the absence of adequate protection and initial observations from a subsequent full-scale field application curing, plastic shrinkage cracking has been an issue in the of wet-mix shotcrete with the natural hemp-based fiber, shotcrete industry. -

All About Fibers

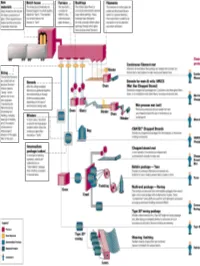

RawRaw MaterialsMaterials ¾ More than half the mix is silica sand, the basic building block of any glass. ¾ Other ingredients are borates and trace amounts of specialty chemicals. Return © 2003, P. Joyce BatchBatch HouseHouse && FurnaceFurnace ¾ The materials are blended together in a bulk quantity, called the "batch." ¾ The blended mix is then fed into the furnace or "tank." ¾ The temperature is so high that the sand and other ingredients dissolve into molten glass. Return © 2003, P. Joyce BushingsBushings ¾The molten glass flows to numerous high heat-resistant platinum trays which have thousands of small, precisely drilled tubular openings, called "bushings." Return © 2003, P. Joyce FilamentsFilaments ¾This thin stream of molten glass is pulled and attenuated (drawn down) to a precise diameter, then quenched or cooled by air and water to fix this diameter and create a filament. Return © 2003, P. Joyce SizingSizing ¾The hair-like filaments are coated with an aqueous chemical mixture called a "sizing," which serves two main purposes: 1) protecting the filaments from each other during processing and handling, and 2) ensuring good adhesion of the glass fiber to the resin. Return © 2003, P. Joyce WindersWinders ¾ In most cases, the strand is wound onto high-speed winders which collect the continuous fiber glass into balls or "doffs.“ Single end roving ¾ Most of these packages are shipped directly to customers for such processes as pultrusion and filament winding. ¾ Doffs are heated in an oven to dry the chemical sizing. Return © 2003, P. Joyce IntermediateIntermediate PackagePackage ¾ In one type of winding operation, strands are collected into an "intermediate" package that is further processed in one of several ways. -

Effect of Hybridization of Glass/Kevlar Fiber on Mechanical Properties of Bast Reinforced Polymer Composites: a Review

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Ivy Union Publishing (E-Journals) American Journal of Polymer Science & Engineering Kumar S et al., American Journal of Polymerhttp://www.ivyunion.org/index.php/ajpse/ Science & Engineering 2017, 5:13-23 Page 1 of 11 Review Article Effect of Hybridization of Glass/kevlar Fiber on Mechanical Properties of Bast Reinforced Polymer Composites: A Review Sandeep Kumar1, Lalta Prasad2, and Vinay Kumar Patel2* 1 Mechanical Engineering Department, S.O.E.T., H.N.B. Garhwal University Srinagar Garhwal- 246174, Uttarakhand, India 2 Department of Mechanical Engineering, Govind Ballabh Pant Engineering College Pauri Garhwal, Uttarakhand, India Abstract Natural fibres are gaining more and more interest as reinforcing materials for polymer composite due to their environmental and economical benefits. Bast fibers is a prominent reinforcement for use in polymeric materials because of its low specific weight and cost, eco-friendly and abundantly available in nature. Several authors manifest the cellulosic fibers based polymeric composites as advantageously used in automobile industries and structural applications, but certain problems have been associated during usage of such fiber such as high water/mosture-uptake and low strength than inorganic fibers. These problems have been reduced to a major extent with enhancements in mechanical properties by the researchers through hybridization of these natural fiber based composites with synthetic fiber (glass/Kevlar). In the present article, we reviewed the effect of hybridization of glass/Kevlar synthetic fibers on mechanical properties of bast fiber (jute, hemp, kenaf, flax) reinforced polymer composites. Keywords : Bast fiber; glass /kevlar fibre; hybrid composites; Mechanical properties Received : November 13, 2016; Accepted: January 8, 2017; Published: January 25, 2017 Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist. -

California Microfiber Update: Textile Perspective

www.materevolve.com California Microfiber Update: Textile Perspective Based on the questions identified by California’s environmental agencies mandated to manage microfibers, Materevolve curated the “California Microfiber Workshop: Science, Innovation & Connection” to bring together 85 California leaders in marine science, policy, and sustainable textile innovation to connect, share knowledge, and discuss solutions for microfiber pollution. 1 Table of Contents About the Authors ………………………………………………………………….. 3 California Microfiber Workshop ………………………………………………...…. 4 Overview to the Issue ……………………………………………………………… 5 Current Efforts: Microfiber Policy, Management, and Research in California ……………………………………………………………………………. 11 Solutions: Consumer and Industry ………………………………………………. 17 Next Steps and Recommendations ………………………………………..……. 21 References …………………………………………………………………………. 25 Other Relevant Workshop Resources …………………………………………... 26 2 About the Authors Krystle Moody Wood is the founder and principal consultant of Materevolve, LLC, a technical textile consultancy driven to lead the evolution of our materials world. Materevolve's mission is to develop and scale innovative regenerative textile systems through the lens of soil, sea and circularity by designing nature-forward experiential learning programs, providing technical consulting to leaders in the textile sector, and fostering trail-blazing collaborations between science, industry, government, and non-profit. With over 13 years of technical textile development experience working for large scale brands (VF, The North Face, Vans, and more), with sustainably minded non-profits (Fibershed, Green Science Policy Institute, 5 Gyres) and with new materials innovators, Krystle brings both a science-led approach and a diverse community to building the future of textiles and sustainable products. Krystle earned her Bachelor’s of Science in Textile Science from the University of California at Davis and has been working towards applying her textile knowledge to support the plastic pollution movement for 4 years. -

Flax, Jute, Hemp, Glass and Carbon Fibers

fibers Article Direct Comparison of the Structural Compression Characteristics of Natural and Synthetic Fiber-Epoxy Composites: Flax, Jute, Hemp, Glass and Carbon Fibers Mike R. Bambach Department of Civil Engineering, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia; [email protected]; Tel.: +61-2-9351-2193 Received: 8 September 2020; Accepted: 25 September 2020; Published: 28 September 2020 Abstract: Recent decades have seen substantial interest in the use of natural fibers in continuous fiber reinforced composites, such as flax, jute and hemp. Considering potential applications, it is of particular interest how natural fiber composites compare to synthetic fiber composites, such as glass and carbon, and if natural fibers can replace synthetic fibers in existing applications. Many studies have made direct comparisons between natural and synthetic fiber composites via material coupon testing; however, few studies have made such direct comparisons of full structural members. This study presents compression tests of geometrically identical structural channel sections fabricated from fiber-epoxy composites of flax, jute, hemp, glass and carbon. Glass fiber composites demonstrated superior tension material coupon properties to natural fiber composites. However, for the same fiber mass, structural compression properties of natural fiber composite channels were generally equivalent to, or in some cases superior to, glass fiber composite channels. This indicates there is substantial potential for natural fibers to replace glass fibers in structural -

Accelerated Aging Study of Ultra High Molecular Weight Polyethylene Yarn and Unidirectional Composites for Ballistic Applications

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Springer - Publisher Connector J Mater Sci (2007) 42:2891–2893 DOI 10.1007/s10853-007-1617-7 LETTER Accelerated aging study of ultra high molecular weight polyethylene yarn and unidirectional composites for ballistic applications S. Chabba Æ M. van Es Æ E. J. van Klinken Æ M. J. Jongedijk Æ D. Vanek Æ P. Gijsman Æ A. C. L. M. van der Waals Received: 12 February 2007 / Accepted: 15 February 2007 / Published online: 20 March 2007 Ó Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2007 Today’s armor systems use a variety of polymeric mate- low density making it an attractive solution for light- rials to provide excellent ballistic protection combined weight ballistic composite applications. Chemically, with low weight and enhanced mobility both for people DyneemaÒ fibers do not contain any aromatic, amide or and vehicles. Typical polymeric materials used in ballistic other chemical groups that can react with common applications are ultra high molecular weight polyethylene chemicals. Hence the fiber’s inertness and stability [2]. such as DyneemaÒ and para-aramid fibers such as Kev- This study evaluates the performance retention of ultra larÒ and TwaronÒ. Law enforcement professionals and high molecular weight polyethylene yarns and composites soldiers use protective vests while performing their duty using accelerated aging technique at elevated temperature over a wide variety of environmental conditions. These and humidity conditions. conditions demand the armor systems to withstand and Ultra high molecular weight polyethylene yarn and perform well under different environmental conditions. -

2021 Fair Guide

Central Kansas Free Fair Premium Guide August 4 - August 9 2021 2021 CENTRAL KANSAS FREE FAIR PRE-FAIR SCHEDULE Sunday, July 25th King/Queen Interviews – K-State Research and Extension, Chisholm Trail District, Dickinson County Office, 2:00 pm Tuesday, July 27th 4-H Dog Show (Armory), 8:00 am Thursday, July 29th 4-H Cat Show (Armory), 6:30 pm Friday, July 30th Favorite Food Show (Thunder Struck Bumpers), 5:00 pm Saturday, July 31st Horticulture Judging Contest (Abilene High School – Agriculture building), 10:00 am Monday, August 2nd 4-H Fashion Revue Judging -Constructed and Purchased ONLINE ENTRY(Emmanuel REQUIRED Church) for ALL4— All -dayH/FFA entries at: 4-H Publicwww.ckff.fairentry.com Fashion Revue (Emmanuel BY Church) July 5th —. 7:00 pm King/Queen Coronation (Emmanuel Church) RodeoONLINE Belt Buckle ENTRY Auction REQUIRED (Shockey & Landes for OPEN Building CLASS) – 7:00 pm LIVESTOCK (beef, sheep, dairy, dairy goat, meat goat, & swine) entries at: www.ckff.fairentry.com BY July 5th. 2 FAIR WEEK SCHEDULE Tuesday, August 3rd Starting at 9:00 am, by schedule Conference Judging (ACC): Visual Arts, Home Environment, Photography, Woodworking, Energy Management, STEM, Entomology, Geology, Forestry 9:00 am – 1:00 pm Walk-in Judging Contests: Photography and Family & Consumer Science Wednesday, August 4th Timed Event Slack — 8:00 am 4-H Foods (ACC) — Starting at 12 pm, by schedule 4-H Clothing Construction and Fiber Arts Judging (ACC) — Starting at 1 pm, by schedule Entry Time for Open Class Entries (except Crops, Floriculture, Horticulture -

BROWN, KATHRYN A., M.S. a Review of the Effects of Australian Wool Marketing Initiatives on the Associations Between Selected Variables in the Global Wool Market

BROWN, KATHRYN A., M.S. A Review of the Effects of Australian Wool Marketing Initiatives on the Associations Between Selected Variables in the Global Wool Market. (2005) Directed by Dr. Peter Kilduff. 194pp. Wool, one of the oldest textile fibers, remains an important textile fiber today. However, wool has been in relative decline for more than 100 years, in the process, shifting from a commodity to a luxury good. Nearly a quarter of a century has passed since the last two significant studies on wool consumption were published - Tisdell’s (1977) review of the global wool market and Kirby and Dardis’s (1992) analysis of demand for textile fibers in the United States textile industry. There is a need to expand and update the literature. In particular, research is needed that tests the association of a broader array of demand and supply-side variables with fiber consumption. This research employs independent variable analysis and odds ratio analysis techniques to build upon previous studies’ explorations of the associations between key independent variables and changes in global mill consumption of Australian wool from 1981 to 2001. Results suggest that fiber prices have the strongest association with Australian wool consumption. Findings also suggest that the associations between the variables reviewed and Australian wool consumption vary greatly across changing periods of wool marketing programs. A REVIEW OF THE EFFECTS OF AUSTRALIAN WOOL MARKETING INITIATIVES ON THE ASSOCIATIONS BETWEEN SELECTED VARIABLES IN THE GLOBAL WOOL MARKET by Kathryn A. Brown A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Greensboro 2005 Approved by ____________________________________ Committee Chair To my parents, George and Gaye, and my sister, Susan. -

Industrial Hemp Fibers: an Overview

Article Industrial Hemp Fibers: An Overview João P. Manaia 1,*, Ana T. Manaia 1 and Lúcia Rodriges 2 1 Laboratory for Wear, Testing & Materials (LED&MAT), Instituto Pedro Nunes, Rua Pedro Nunes, 3030-199 Coimbra, Portugal; [email protected] 2 CITEVE, Rua Fernando Mesquita, 2785, 4760-034 Vila Nova de Famalicão, Portugal; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +351-963-128-954 Received: 16 October 2019; Accepted: 26 November 2019; Published: 2 December 2019 Abstract: Industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa) is one of the most available and widely produced bast fibers with high cellulose content. Interest in these fibers is warranted due to environmental protection challenges as well as their inherent properties such as low density, high specific strength, and stiffness. In addition, advanced research and progress have gone into increasing their mechanical performance through surface treatments and in the development of new materials. The most promising application for hemp fibers is as reinforcement in polymeric composites or through hybridization. Nonetheless, more research is needed to improve their properties and expand their range of applications. The biodegradability issue is one problem that must be addressed when considering long life-cycle applications as the reproducibility of these composites’ final properties. This review is a comprehensive literature review on hemp fibers. It includes hemp fibers’ chemical and mechanical properties, surface modifications, hybrid composites, as well as current and future applications. Keywords: hemp fibers; surface treatments; hybrid composites; mechanical properties; industrial applications 1. Introduction Environmental protection is one of the greatest challenges facing the current generation [1]. -

Covid-19 Impact on Global Semi-Synthetic Fiber

+44 20 8123 2220 [email protected] Covid-19 Impact on Global Semi-synthetic Fiber Market 2020 by Manufacturers, Regions, Type and Application, Forecast to 2026 https://marketpublishers.com/r/C52813947367HEN.html Date: November 2020 Pages: 175 Price: US$ 3,480.00 (Single User License) ID: C52813947367HEN Abstracts The research team projects that the Semi-synthetic Fiber market size will grow from XXX in 2019 to XXX by 2026, at an estimated CAGR of XX. The base year considered for the study is 2019, and the market size is projected from 2020 to 2026. The prime objective of this report is to help the user understand the market in terms of its definition, segmentation, market potential, influential trends, and the challenges that the market is facing with 10 major regions and 30 major countries. Deep researches and analysis were done during the preparation of the report. The readers will find this report very helpful in understanding the market in depth. The data and the information regarding the market are taken from reliable sources such as websites, annual reports of the companies, journals, and others and were checked and validated by the industry experts. The facts and data are represented in the report using diagrams, graphs, pie charts, and other pictorial representations. This enhances the visual representation and also helps in understanding the facts much better. By Market Players: ALBINI Sarvoday Textiles TESTA ALUMO Veratex Lining MONTI Bombay Rayon Acorn Fabrics S.I.C Covid-19 Impact on Global Semi-synthetic Fiber Market 2020 by Manufacturers, Regions, Type and Application, Fo..