A Palette for Genius Japanese Water Jars for the Tea Ceremony

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vocabulary: Koryo Open Work Design Celadon Glaze Korean Celadon: Cheong-Ja Buddhism Leatherhard Clay Sanggam: Inlaid Design Symbols

Lesson Title: Koryo (12-13th Century) Celadon Pottery and Korean Aesthetics Class and Grade level(s): High School and/or Junior High Art Goals and Objectives: The student will be able to: *identify Korean Koryo Celadon pottery as an original Korean Art form. *understand that the Korean aesthetic is rooted in nature. *utilize design elements of Koryo pottery in their own ceramic projects. Vocabulary: Koryo Open work design Celadon Glaze Korean Celadon: Cheong-ja Buddhism Leatherhard clay Sanggam: Inlaid Design Symbols 12th century Unidentified, Korean, Koryo period Stoneware bowl with celadon glaze. This undecorated ceramic bowl with incurving rim replicates the form of metal alms bowls carried by Buddhist monks for receiving food offerings from devotees. The ceramic version was probably used for the same purpose and would have been a gift to a monastery from a noble patron. Primary source bibliography: Freer collection celadon images: http://www.asia.si.edu/collections/korean_highlights.asp News: Koryo Pottery Was Headed for Kaesong http://english.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2007/10/12/2007101261013.html History http://search.freefind.com/find.html?id=70726870&pageid=r&mode=all&n=0& query=korea+history Korean History and Art Sites http://search.freefind.com/find.html?oq=korea+art&id=70726870&pageid=r&_c harset_=UTF- 8&bcd=%C3%B7&scs=1&query=korea+art&Find=Search&mode=ALL&searc h=all Other resources used: A Single Shard by Linda Sue Park; Scholastic Inc., copyright 2001 http://www.lindasuepark.com/books/singleshard/singleshard.html Required materials/supplies: Clay studio tools, White clay, Celadon glaze, White and black slip Procedure: Introduction: Korean Koryo Celadon (Cheong-ja) Ceramics Korean pottery dates back to the Neolithic age. -

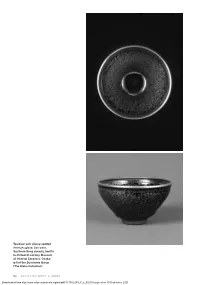

(B. 1948) Kamada Kōji Is Known for His Mastery of the Difficult Tenmoku

KAMADA KŌJI (b. 1948) Kamada Kōji is known for his mastery of the difficult tenmoku (rabbit’s hair) glaze, a technique that originated in 10th century Song Dynasty China and entered Japan during the Muromachi period two centuries later. Kamada has revitalized the technique by applying the traditional glaze to his modernized, but still functional, teaware that challenge the concepts of balance and presence. His works serve as an updated canvas for these established glaze techniques, allowing form and glaze to beautifully complement one another. 1948 Born in Kyoto 1968 Trained in Gojōzaka with Shimizu Tadashi 1971 Graduated from Kyoto Ceramics Training School, became an instructor Began his study of tenmoku glazes 1973 Entered the 2nd Japan Craft Association, Kinki District 1976 Became an official member of the Japan Craft Society 1977 Resigned as instructor for the Kyoto prefectural government and began concentrating exclusively on creating ceramics 1982 With the closing of the public Gojōzaka kiln, he acquired his own gas kiln 1988 Studied under National Living Treasure, Shimizu Uichi 1990 Became an official member of Japan Sencha (Tea) Craft Association 2000 Juror for Nihon dentō kogeiten (Japan Traditional Crafts Exhibition) Awards: 1987 Kyoto Board of Education Chairperson's Award, the 16th Japan Craft Association Exhibition Kinki District Selected Solo Exhibitions: 1978 Osaka Central Gallery (also '79 and '80) 1980 Takashimaya Art Gallery, Kyoto (eight more shows through ‘03, then ‘13) 1984 Takashimaya Art Gallery, Nihonbashi, Tokyo -

Hand and Wheel: Contemporary Japanese Clay

HAND AND WHEEL Contemporary Japanese Clay NOvember 1, 2014 – OCTober 18, 2015 PORTLAND ART MUSEUM, OREGON HAND AND WHEEL Contemporary Japanese Clay Among the great ceramic traditions of the world, ceramics. Yet this core population of consumers the Japanese alone sustain a thriving studio pot- is, on its own, insufficient to account for the cur- ter industry on a grand scale. More than 10,000 rent boom in both creativity and critical acclaim. Japanese potters make a living crafting ceramics Today, museums in Japan and abroad and private to adorn the table for everyday life, in addition to collectors in the West have assumed a prominent specialized wares for the tea ceremony. Whether role in nurturing Japanese ceramics—especially made from rough, unglazed stoneware or refined large-scale pieces and the work of the avant- porcelain, these intimately scaled art works are an garde artists who push the boundaries of tech- indispensable part of Japanese rituals of dining nique, material, and form. and hospitality. The high demand of domestic Many contemporary Japanese ceramic artists consumers for functional vessels, as well as their —especially those who came of age in the informed connoisseurship of regional and even 1950s—are exceptionally skilled at throwing pots 33 the individual styles of famous masters, underlies on a wheel. They often prefer to use traditional of the firing process. Here, the pieces by Naka- the commercial success of Japanese studio wood-fired kilns, embracing the unpredictability zato Takashi, Ōtani Shirō, and Yoshida Yoshihiko, among others, rely on yōhen, or “fire-changes,” for much of their visual impact. -

Tianmu Bowls

GLOBAL EA HUT Tea & Tao Magazine 國際茶亭 May 2018 Tianmu天目 Bowls GLOBAL EA HUT ContentsIssue 76 / May 2018 Tea & Tao Magazine Cloud祥雲寺 Temple This month, we are excited to dive into the world of tea bowls, exploring how to choose bowls for tea and the history of China’s most Love is famous bowls, called “tianmu.” And we have a great green tea to drink as we discuss the his- changing the world tory, production and lore of tianmu as well as some modern artists making tianmu bowls. bowl by bowl Features特稿文章 13 The Glory of Tianmu By Wang Duozhi (王多智) 25 Tianmu Kilns in 03 Fujian By Li Jian’an (栗建安) 42 Yao Bian Tianmu 13 By Lin Jinzhong (林錦鐘) 45 Shipwrecked Tianmu By Huang Hanzhang (無黃漢彰) 33 Traditions傳統文章 53 03 Tea of the Month “Cloud Temple,” Fresh Spring Green Tea Mingjian, Nantou, Taiwan 21 Cha Dao How to Hold the Bowl By Jing Ren (淨仁) Teaware Artisans p. 33 Lin Jinzhong, by Wu De (無的) p. 53 Wang Xi Rui, by Wu De (無的) 祥 © 2018 by Global Tea Hut 59 Special Offer All rights reserved. Wang Xi Rui Tianmu Bowls 雲 No part of this publication may be re- 寺 produced, stored in a retrieval system 61 TeaWayfarer or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, pho- Erin Farb, USA tocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission from the copyright owner. n May, TaiwanFrom really warms up and we startthe turn- cover teaware in atEditor least one issue, which we are presenting ing more to lighter teas like green teas, white teas in this very issue. -

Piese De Artă Decorativă Japoneză Din Colecţia Muzeului Ţării Crișurilor

Piese de artă decorativă japoneză din Colecţia Muzeului Ţării Crișurilor și colecţiile particulare din Oradea TAMÁS Alice* Japanese decorative art pieces from the collections of Criş County Museum and private properties in Oradea - Abstract - The history of japanese pottery reveled the evolution of ceramic arts styles and technics and also the activities of many masters, craftsmans, artists by the different periods of Japan history like Jomon (8000B.C.- 300B.C.), Yayoi (300B.C.-300A.D.), Kofun (300A.D.- 710A.D.), Nara (710-794), Heian (794-1192), Kamakura (1192-1333), Muromachi (1333- 1573), Momoyama (1573-1603), Edo(1603-1868), Meiji (1868-1912), Taisho (1912-1926) and Showa (1926-1988). The most beautiful Satsuma pottery that found in the collections of the Criș County Museum and private properties in Oradea, was made in Meiji periode, for the occidental art consumers and described historical scenes, that was painted with many technics like underglase, overglase, Moriaje (rice) Keywords: Japanese pottery, tradition, industry, Satsuma, art styles, În urma investigaţiilor arheologice şi a datării cu carbon radioactiv s-a ajuns la concluzia că arhipeleagul japonez, cândva parte din continentul eurasiatic a fost locuit din Pleistocen (Era glaciară), uneltele din piatră găsite datând dinainte de 30.000 î. Hr., iar meș- teșugul și arta ceramicii se practica de mai bine de 12.000 de ani. Istoria culturii și civilizaţiei din arhipeleagul Japonez cunoaște o împărţire pe perioade. Urmărind perioadele istorice din cele mai vechi timpuri și până azi se poate constata o evoluţie a spiritualităţii, a mentalităţilor precum și a diverselor tehnici de execuţie a ceramicii japoneze, având perioade incipiente, de apogeu și declin de-a lungul timpului. -

Kraak Porcelain

Large Dishes from Jingdezhen and Longquan around the World Dr Eva Ströber Keramiekmuseum Princessehof, NL © Eva Ströber 2010 Cultures of Ceramics in Global History, 1300-1800 University of Warwick, 22-24 April 2010 Global History Arts & Humanities & Culture Centre Research Council http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/history/ghcc/research/globalporcelain/conference Large Dishes from Jingdezhen and Longquan around the World The talk will be about the huge success of a type of Chinese porcelain the Chinese themselves had indeed no use for: large serving dishes, large meaning more than 35 cm in diam. The most common blue and white type was made in Jingdezhen, the Celadon type in the Longquan kilns in Southern Zhejiang and Northern Fujian. Another type of large dishes, the Zhangzhou type, was produced in the kilns of Zhangzhou, Fujian. The focus will be on three markets these oversized dishes were made for: the Muslim markets of the Middle East, particularly Persia, Turkey and the Mughal empire, SE Asia including what is now Indonesia, and Japan. By miniatures, drawings, paintings or old photographs it will be illustrated, how these large Chinese dishes were used in a non Chinese social and cultural context. The Chinese Bowl The Chinese themselves, as can be seen on the famous painting of a literati gathering from the Song – dynasty of the 12th century, dined from rather small sized tableware. The custom to eat from small dishes and particularly from bowls started in the Song dynasty and spread to many countries in SE Asia. It has not changed even to this very day. -

Stoneware Tea Bowl. Chun Glaze. Chun Interior. Height 7.6Cm, Diameter 11Cm

PS1 - Stoneware tea bowl. Chun glaze. Chun interior. Height 7.6cm, diameter 11cm. SOLD PS1 PS2 - Stoneware tea bowl. Titanium glaze over tenmoku. Tenmoku interior. Height 8.7cm, diameter 9.7cm. £45.00 PS2 PS3 - Stoneware tea bowl. Tenmoku glaze with ilmenite decoration. Chun interior. Height 9.2cm, diameter 9.6cm. SOLD PS3 PS4 - Stoneware tea bowl. Copper red glaze. Chun interior. Height 8.6cm, diameter 10cm. SOLD PS4 PS5 - Stoneware tea bowl. Tenmoku glaze. Chun interior. Height 9.7cm, diameter 8.6cm. SOLD PS5 PS6 - Porcelain tea bowl. Jade green glaze. Copper red interior. Height 6.6cm, diameter 11cm. SOLD PS6 PS7 - Stoneware tea bowl. Copper red glaze with ilmenite decoration. Chun interior. Height 9.6cm, diameter 8.5cm. £45.00 PS7 PS8 - Porcelain tea bowl. Layered chun and tenmoku glaze. Tenmoku interior. Height 8.4cm, diameter 9.3cm. SOLD PS8 PS9 - Stoneware tea bowl. Titanium glaze over tenmoku. Tenmoku interior. Height 7cm, diameter 11.7cm. £45.00 PS9 PS10 - Stoneware tea bowl. Celadon and copper red glaze. Celadon interior. Height 9.3cm, diameter 8.5cm. £45.00 PS10 PS11 - Stoneware tea bowl. Incised titanium glaze over tenmoku glaze. Tenmoku interior. Height 8.8cm, diameter 11.2cm. SOLD PS11 PS12 - Porcelain tea bowl. Copper red glaze with ilmenite decoration. Chun interior. Height 7.5cm, diameter 9.5cm. £45.00 PS12 PS13 - Stoneware tea bowl. Unglazed Yixing clay body. Chun interior. Height 7.7cm, diameter 9.7cm. SOLD PS13 PS14 - Stoneware tea bowl. Layered chun and tenmoku glaze. Tenmoku interior. Height 9.4cm, diameter 9.2cm. SOLD PS14 PS15 - Stoneware tea bowl. -

Comparative Study of Black and Gray Body Celadon Shards Excavated from Wayaoyang Kiln in Longquan, China

Microchemical Journal 126 (2016) 274–279 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Microchemical Journal journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/microc Comparative study of black and gray body celadon shards excavated from Wayaoyang kiln in Longquan, China Hongying Duan a,b,⁎, Dongge Ji a,b, Yinzhong Ding a,b, Guangyao Wang c, Jianming Zheng d, Guanggui Zhou e, Jianmin Miao a,b a Key Scientific Research Base of Ancient Ceramics (the Palace Museum), State Administration of Cultural Heritage, Beijing 100009, China b Conservation Department, the Palace Museum, Beijing 100009, China c Department of Objects and Decorative Arts, the Palace Museum, Beijing 100009, China d Zhejiang Provincial Cultural Relics Archaeological Research Institute, Hangzhou, Zhejiang 310014, China e The Museum of Longquan City, Longquan, Zhejiang 323700, China article info abstract Article history: Longquan celadon is one of the most valuable treasures in Chinese ceramic history. Representative products are Received 8 August 2015 Ge ware (Ge meaning elder brother, black body celadon) and Di ware (Di meaning younger brother, gray body Received in revised form 12 December 2015 celadon) of the Song Dynasty (960–1279 A.D.). In this study, Ge and Di ware shards excavated from Wayaoyang Accepted 12 December 2015 kiln site in Longquan were collected and studied. Chemical and crystallite composition, microstructure, body and Available online 19 December 2015 glaze thickness, firing temperature and glaze reflectance spectrum were observed and examined. Differences in Keywords: raw materials and manufacturing technology between Ge and Di ware were studied. Based on the results and Longquan Ge ware historical background, it was speculated that some Ge wares from Wayaoyang kiln site might be the test products Longquan Di ware of jade-like black body celadon for the imperial court. -

Antique Pair Japanese Meiiji Imari Porcelain Vases C1880

anticSwiss 29/09/2021 17:25:52 http://www.anticswiss.com Antique Pair Japanese Meiiji Imari Porcelain Vases C1880 FOR SALE ANTIQUE DEALER Period: 19° secolo - 1800 Regent Antiques London Style: Altri stili +44 2088099605 447836294074 Height:61cm Width:26cm Depth:26cm Price:2250€ DETAILED DESCRIPTION: A monumental pair of Japanese Meiji period Imari porcelain vases, dating from the late 19th Century. Each vase features a bulbous shape with the traditional scalloped rim, over the body decorated with reserve panels depicting court garden scenes and smaller shaped panels with views of Mount Fuji on chrysanthemums and peonies background adorned with phoenixes. Each signed to the base with a three-character mark and on the top of each large panel with a two-character mark. Instill a certain elegance to a special place in your home with these fabulous vases. Condition: In excellent condition, with no chips, cracks or damage, please see photos for confirmation. Dimensions in cm: Height 61 x Width 26 x Depth 26 Dimensions in inches: Height 24.0 x Width 10.2 x Depth 10.2 Imari ware Imari ware is a Western term for a brightly-coloured style of Arita ware Japanese export porcelain made in the area of Arita, in the former Hizen Province, northwestern Ky?sh?. They were exported to Europe in large quantities, especially between the second half of the 17th century and the first half of the 18th century. 1 / 4 anticSwiss 29/09/2021 17:25:52 http://www.anticswiss.com Typically Imari ware is decorated in underglaze blue, with red, gold, black for outlines, and sometimes other colours, added in overglaze. -

Mikawachi Pottery Centre

MIKAWACHI POTTERY CENTRE Visitors’ Guide ●Mikawachi Ware – Highlights and Main Features Underglaze Blue ─ Underglaze Blue … 02 Skilful detail and shading Chinese Children … 04 create naturalistic images Openwork Carving … 06 Hand-forming … 08 Mikawachi Ware - … 09 Hand crafted chrysanthemums Highlights Relief work … 10 and Eggshell porcelain … 11 Main Features ● A Walkerʼs guide to the pottery studios e History of Mikawachi Ware … 12 Glossary and Tools … 16 Scenes from the Workshop, 19th – 20th century … 18 Festivals at Mikawachi Pottery ʻOkunchiʼ … 20 Hamazen Festival /The Ceramics Fair … 21 Visitorsʼ Map Overview, Kihara, Enaga … 22 Mikawachi … 24 Mikawachi-things to See and Learn … 23 Transport Access to Mikawachi … 26 ʻDamiʼ – inlling with cobalt blue is is a technique of painting indigo-coloured de- Underglaze blue work at Mikawachi is described signs onto a white bisque ground using a brush as being “just like a painting”. When making images soaked in cobalt blue pigment called gosu. e pro- on pottery, abbreviations and changes occur natural- cess of painting the outl9 of motifs onto biscuit-red ly as the artist repeats the same motif many times pieces and adding colour is called etsuke. Filling in over – it becomes stylised and settles into an estab- the outlined areas with cobalt blue dye is specically lished ʻpatternʼ. At Mikawachi, however, the painted known as dami. e pot is turned on its side, and a designs do not pass through this transformation; special dami brush steeped in gosu is used to drip the they are painted just as a two-dimensional work, coloured pigment so it soaks into the horizontal sur- brushstroke by brushstroke. -

Liquidity, Technicity, and the Predictive Turn in Chinese Ceramics

Tea bowl with silvery-spotted tenmoku glaze, Jian ware, Southern Song dynasty, twelfth to thirteenth century. Museum of Oriental Ceramics, Osaka; gift of the Sumitomo Group (The Ataka Collection). 24 doi:10.1162/GREY_a_00230 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/GREY_a_00230 by guest on 30 September 2021 Liquidity, Technicity, and the Predictive Turn in Chinese Ceramics JEFFREY MOSER Jeff Wall’s notion of liquid intelligence turns on the dialectic of modernity. On one side of the divide are the dry mechanisms of the camera, which metaphorically and literally express the industrial processes that brought them into being. On the other side is water, which “symbolically represents an archaism in photography, one that is admitted in the process, but also excluded, contained or channelled by its hydraulics.” 1 Wall’s attraction to liquidity is unreservedly nostalgic—it harkens back to archaic processes and what he understands as the ever more remote possibility of fortuity in art-making—and it seeks to find, in the developing fluid of the photograph, a bridge back to the “sense of immersion in the incalculable” that modernity has alienated. 2 For him, liquidity and chance are not simply of the past, they have been made past by the totality of a “modern vision” that inex - orably subjugates them through industry and design. 3 Wall’s formulation implicitly probes the semantic contradiction that imbues Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels’s famous passage with such force: Where, he inquires, is the liquid elided when “all that is solid melts into air?” 4 The juxtaposition of Wall’s essay “Photography and Liquid Intelligence” with his Milk (1984) raises the tension simmering in Wall’s formula. -

Shoji Hamada: 40 Years on List of Works

Shoji Hamada: 40 Years On List of Works Set Of Six Hexagonal Dishes SOLD With a signed, fitted box stoneware with tenmoku and nuka glaze. each 3.5 x 13 cms 1 3/8 x 5 1/8 inches (box 16 x 18) (SH021) Okinawa Style Teabowl 1970 £ 4,500.00 Provenance: from The Martha Longenecker Collection, USA. Published in Mingei International Museum, Martha W. Longenecker, ed., Mingei of Japan: The Legacy of The Founders - Soetsu Yanagi, Shoji Hamada, Kanjiro Kawai, (California, 2006), p. 60-61 and p. 66, 70 stoneware with Okinawa style enamel glazing. 8.5 x 13 cms 3 3/8 x 5 1/8 inches (SH043) Kaki Square Vase c1960 SOLD Glazed stoneware, with wax resist design see 'Shoji Hamada, A Potter’s Way and Work' by Susan Peterson, 1974, p122 showing Hamada making this form and p152 showing a group of pieces which includes a very similar version. 20 x 12 x 7 cms 7 7/8 x 4 3/4 x 2 3/4 inches (SH045) Tenmoku Square Bottle Vase 1960 £ 2,750.00 Stoneware with tenmoku glaze and finger-wipe design ash glazed top. 17 x 10 x 10 cms 6 3/4 x 4 x 4 inches (SH046) Teabowl 1965 £ 2,200.00 Provenance: collection of Mike O'Connor piece to left of image. stoneware with nuka glaze and dark green rim. 11 x 11.5 cms 4 3/8 x 4 1/2 inches (SH050) Shoji Hamada: 40 Years On List of Works Teabowl 1965 £ 2,200.00 Provenance: collection of Mike O'Connor piece to right of image stoneware with nuka glaze and dark green rim.