Evidence from the Hollywood Studio Era F. Andrew Hanssen John E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Files on the Famous–And Infamous

Federal Files on the Famous–and Infamous The collections of personnel records at the National Archives available. Digital copies of PEPs can be purchased on CD/DVDs. include files that document military and civilian service for The price of the disc depends on the number of pages contained persons who are well known to the public for many reasons. in the original paper record and range from $20 (100 pages or These individuals include celebrated military leaders, less) to $250 (more than 1,800 pages). For more information or Medal of Honor recipients, U.S. Presidents, members of to order copies of digitized PEP records only, please write to pep. Congress, other government officials, scientists, artists, [email protected]. Archival staff are in the process of identifying entertainers, and sports figures—individuals noted for the records of prominent civilian employees whose names will personal accomplishments as well as persons known for their be added to the list. Other individuals whose records are now infamous activities. available for purchase on CD are: The military service departments and NARA have Creighton W. Abrams, Grover Cleveland Alexander, identified over 500 such military records for individuals Desi Arnaz, Joe L. Barrow, John M. Birch, Hugo L. Black, referred to as “Persons of Exceptional Prominence” (PEP). Gregory Boyington, Prescott S. Bush, Smedley Butler, Evans Many of these records are now open to the public earlier F. Carlson, William A. Carter, Adna R. Chaffee, Claire than they otherwise would have been (62 years after the Chennault, Mark W. Clark, Benjamin O. Davis. separation dates) as the result of a special agreement that Also, George Dewey, William Donovan, James H. -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

One-Word Movie Titles

One-Word Movie Titles This challenging crossword is for the true movie buff! We’ve gleaned 30 one- word movie titles from the Internet Movie Database’s list of top 250 movies of all time, as judged by the website’s users. Use the clues to find the name of each movie. Can you find the titles without going to the IMDb? 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 EclipseCrossword.com © 2010 word-game-world.com All Rights Reserved. Across 1. 1995, Mel Gibson & James Robinson 5. 1960, Anthony Perkins & Vera Miles 7. 2000, Russell Crowe & Joaquin Phoenix 8. 1996, Ewan McGregor & Ewen Bremner 9. 1996, William H. Macy & Steve Buscemi 14. 1984, F. Murray Abraham & Tom Hulce 15. 1946, Cary Grant & Ingrid Bergman 16. 1972, Laurence Olivier & Michael Caine 18. 1986, Keith David & Forest Whitaker 21. 1979, Tom Skerritt, Sigourney Weaver 22. 1995, Robert De Niro & Sharon Stone 24. 1940, Laurence Olivier & Joan Fontaine 25. 1995, Al Pacino & Robert De Niro 27. 1927, Alfred Abel & Gustav Fröhlich 28. 1975, Roy Scheider & Robert Shaw 29. 2000, Jason Statham & Benicio Del Toro 30. 2000, Guy Pearce & Carrie-Anne Moss Down 2. 2009, Sam Worthington & Zoe Saldana 3. 2007, Patton Oswalt & Iam Holm (voices) 4. 1958, James Stuart & Kim Novak 6. 1974, Jack Nicholson & Faye Dunaway 10. 1982, Ben Kingsley & Candice Bergen 11. 1990, Robert De Niro & Ray Liotta 12. 1986, Sigourney Weaver & Carrie Henn 13. 1942, Humphrey Bogart & Ingrid Bergman 17. -

Raoul Walsh to Attend Opening of Retrospective Tribute at Museum

The Museum of Modern Art jl west 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel. 956-6100 Cable: Modernart NO. 34 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE RAOUL WALSH TO ATTEND OPENING OF RETROSPECTIVE TRIBUTE AT MUSEUM Raoul Walsh, 87-year-old film director whose career in motion pictures spanned more than five decades, will come to New York for the opening of a three-month retrospective of his films beginning Thursday, April 18, at The Museum of Modern Art. In a rare public appearance Mr. Walsh will attend the 8 pm screening of "Gentleman Jim," his 1942 film in which Errol Flynn portrays the boxing champion James J. Corbett. One of the giants of American filmdom, Walsh has worked in all genres — Westerns, gangster films, war pictures, adventure films, musicals — and with many of Hollywood's greatest stars — Victor McLaglen, Gloria Swanson, Douglas Fair banks, Mae West, James Cagney, Humphrey Bogart, Marlene Dietrich and Edward G. Robinson, to name just a few. It is ultimately as a director of action pictures that Walsh is best known and a growing body of critical opinion places him in the front rank with directors like Ford, Hawks, Curtiz and Wellman. Richard Schickel has called him "one of the best action directors...we've ever had" and British film critic Julian Fox has written: "Raoul Walsh, more than any other legendary figure from Hollywood's golden past, has truly lived up to the early cinema's reputation for 'action all the way'...." Walsh's penchant for action is not surprising considering he began his career more than 60 years ago as a stunt-rider in early "westerns" filmed in the New Jersey hills. -

Executive Order 13978 of January 18, 2021

6809 Federal Register Presidential Documents Vol. 86, No. 13 Friday, January 22, 2021 Title 3— Executive Order 13978 of January 18, 2021 The President Building the National Garden of American Heroes By the authority vested in me as President by the Constitution and the laws of the United States of America, it is hereby ordered as follows: Section 1. Background. In Executive Order 13934 of July 3, 2020 (Building and Rebuilding Monuments to American Heroes), I made it the policy of the United States to establish a statuary park named the National Garden of American Heroes (National Garden). To begin the process of building this new monument to our country’s greatness, I established the Interagency Task Force for Building and Rebuilding Monuments to American Heroes (Task Force) and directed its members to plan for construction of the National Garden. The Task Force has advised me it has completed the first phase of its work and is prepared to move forward. This order revises Executive Order 13934 and provides additional direction for the Task Force. Sec. 2. Purpose. The chronicles of our history show that America is a land of heroes. As I announced during my address at Mount Rushmore, the gates of a beautiful new garden will soon open to the public where the legends of America’s past will be remembered. The National Garden will be built to reflect the awesome splendor of our country’s timeless exceptionalism. It will be a place where citizens, young and old, can renew their vision of greatness and take up the challenge that I gave every American in my first address to Congress, to ‘‘[b]elieve in yourselves, believe in your future, and believe, once more, in America.’’ Across this Nation, belief in the greatness and goodness of America has come under attack in recent months and years by a dangerous anti-American extremism that seeks to dismantle our country’s history, institutions, and very identity. -

The Making of Hollywood Production: Televising and Visualizing Global Filmmaking in 1960S Promotional Featurettes

The Making of Hollywood Production: Televising and Visualizing Global Filmmaking in 1960s Promotional Featurettes by DANIEL STEINHART Abstract: Before making-of documentaries became a regular part of home-video special features, 1960s promotional featurettes brought the public a behind-the-scenes look at Hollywood’s production process. Based on historical evidence, this article explores the changes in Hollywood promotions when studios broadcasted these featurettes on television to market theatrical films and contracted out promotional campaigns to boutique advertising agencies. The making-of form matured in the 1960s as featurettes helped solidify some enduring conventions about the portrayal of filmmaking. Ultimately, featurettes serve as important paratexts for understanding how Hollywood’s global production work was promoted during a time of industry transition. aking-of documentaries have long made Hollywood’s flm production pro- cess visible to the public. Before becoming a staple of DVD and Blu-ray spe- M cial features, early forms of making-ofs gave audiences a view of the inner workings of Hollywood flmmaking and movie companies. Shortly after its formation, 20th Century-Fox produced in 1936 a flmed studio tour that exhibited the company’s diferent departments on the studio lot, a key feature of Hollywood’s detailed division of labor. Even as studio-tour short subjects became less common because of the restructuring of studio operations after the 1948 antitrust Paramount Case, long-form trailers still conveyed behind-the-scenes information. In a trailer for The Ten Commandments (1956), director Cecil B. DeMille speaks from a library set and discusses the importance of foreign location shooting, recounting how he shot the flm in the actual Egyptian locales where Moses once walked (see Figure 1). -

Steinhart Runaway Hollywood Chapter3

Chapter 3 Lumière, Camera, Azione! the personnel and practices of hollywood’s mode of international production as hollywood filmmakers gained more experience abroad over the years, they devised various production strategies that could be shared with one another. A case in point: in May 1961, Vincente Minnelli was preparing the production of Two Weeks in Another Town (1962), part of which he planned to shoot in Rome. Hollywood flmmaker Jean Negulesco communicated with Minnelli, ofering some advice on work- ing in Italy, where Negulesco had directed portions of Tree Coins in the Fountain (1954) and Boy on a Dolphin (1957) and at the time was producing his next flm, Jessica (1962): I would say that the most difcult and the most important condition of mak- ing a picture in Italy is to adapt yourself to their spirit, to their way of life, to their way of working. A small example: Tis happened to me on location. As I arrive on the set and everything is ready to be done at 9 o’clock—the people are having cofee. Now, your assistant also is having cofee—and if you are foolish enough to start to shout and saying you want to work, right away you’ll have an unhappy crew and not the cooperation needed for the picture. But if you have cofee with them, they will work for you with no time limit or no extra expense.1 Negulesco’s letter underscores a key lesson that Hollywood moviemakers learned overseas when confronted with diferent working hours, production practices, and cultural customs. -

Blackadder Goes Forth Audition Pack

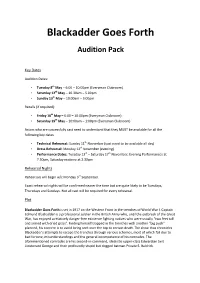

Blackadder Goes Forth Audition Pack Key Dates Audition Dates: • Tuesday 8 th May – 6:00 – 10:00pm (Everyman Clubroom) • Saturday 12 th May – 10.30am – 5.00pm • Sunday 13 th May – 10:00am – 3.00pm Recalls (if required): • Friday 18 th May – 6:00 – 10:00pm (Everyman Clubroom) • Saturday 19 th May – 10:00am – 1:00pm (Everyman Clubroom) Actors who are successfully cast need to understand that they MUST be available for all the following key dates • Technical Rehearsal: Sunday 11 th November (cast need to be available all day) • Dress Rehearsal: Monday 12 th November (evening) • Performance Dates: Tuesday 13 th – Saturday 17 th November; Evening Performances at 7.30pm, Saturday matinee at 2.30pm Rehearsal Nights Rehearsals will begin w/c Monday 3 rd September. Exact rehearsal nights will be confirmed nearer the time but are quite likely to be Tuesdays, Thursdays and Sundays. Not all cast will be required for every rehearsal. Plot Blackadder Goes Forth is set in 1917 on the Western Front in the trenches of World War I. Captain Edmund Blackadder is a professional soldier in the British Army who, until the outbreak of the Great War, has enjoyed a relatively danger-free existence fighting natives who were usually "two feet tall and armed with dried grass". Finding himself trapped in the trenches with another "big push" planned, his concern is to avoid being sent over the top to certain death. The show thus chronicles Blackadder's attempts to escape the trenches through various schemes, most of which fail due to bad fortune, misunderstandings and the general incompetence of his comrades. -

Ronald Davis Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts

Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts in America Southern Methodist University The Southern Methodist University Oral History Program was begun in 1972 and is part of the University’s DeGolyer Institute for American Studies. The goal is to gather primary source material for future writers and cultural historians on all branches of the performing arts- opera, ballet, the concert stage, theatre, films, radio, television, burlesque, vaudeville, popular music, jazz, the circus, and miscellaneous amateur and local productions. The Collection is particularly strong, however, in the areas of motion pictures and popular music and includes interviews with celebrated performers as well as a wide variety of behind-the-scenes personnel, several of whom are now deceased. Most interviews are biographical in nature although some are focused exclusively on a single topic of historical importance. The Program aims at balancing national developments with examples from local history. Interviews with members of the Dallas Little Theatre, therefore, serve to illustrate a nation-wide movement, while film exhibition across the country is exemplified by the Interstate Theater Circuit of Texas. The interviews have all been conducted by trained historians, who attempt to view artistic achievements against a broad social and cultural backdrop. Many of the persons interviewed, because of educational limitations or various extenuating circumstances, would never write down their experiences, and therefore valuable information on our nation’s cultural heritage would be lost if it were not for the S.M.U. Oral History Program. Interviewees are selected on the strength of (1) their contribution to the performing arts in America, (2) their unique position in a given art form, and (3) availability. -

Bob Thomas Papers, 1914-2004

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt300030cb No online items Bob Thomas papers, 1914-2004 Finding aid prepared by Sarah Sherman and Julie Graham; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] ©2005 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Bob Thomas papers, 1914-2004 PASC 299 1 Title: Bob Thomas papers Collection number: PASC 299 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 28.5 linear ft.(57 boxes and 3 flat boxes) Date (bulk): Bulk, 1930-1989 Date (inclusive): 1914-2004 (bulk 1930-1980s) Abstract: Since 1944 Bob Thomas has written thousands of Hollywood syndicated columns for The Associated Press and has authored (or co-authored) at least thirty books relating to the entertainment industry. The collection consists of materials related to his professional career as a writer and includes manuscripts, research and photographs for books by Thomas as well as Associated Press columns, research files, and a small amount of printed ephemera. Language of Materials: Materials are in English. Physical Location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Creator: Thomas, Bob, 1922- Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Use of audio materials may require production of listening copies. -

STOKOWSKI “VIRGINIA.” Phone Alex 3491 I

-----— Audience Watches Barnes the fine points of disrobing There’s No entertainingly, yet without disturb- Just Gratitude Real ing the censors. in Theaters This Week Strip Tease, Binnie proved an apt pupil. The Washington scene was soon filmed. , Ex-Lifeguard Ronald Reagan Saved Photoplays Reacts .. .. ■■■■■' ■■■ next was t !■■■■■■.. -|| Properly Rogeirs task to record an audience reaction to the Barnes Was Thanked Once WEEK OF MAY 4 I SUNDAY j MONDAY TUESDAY | WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY 8ATURDAY B> the Associated Press. Many, Only Several didn't AmHiamw I ‘This-Thin?: Called This Thing Called “Arise, My Love. and “Ariw- My Love." and Melody and Moon- “Melody and Moon- “South of Suez" and HOLLYWOOD. undressing. attempts Bt the Associated Press. Mcaatmy and “Light of t” and of "Boss of Bullion HOLLYWOOD. Love.. nnd Love*. pnd Xhe Devll Com. The Devil Com- light Ugl "Light What’s the best way of getting a go so well. Finally he said to Misa 6th and G Bta. 81 1 “Escape toGlory“Escape to Glory_mands_/|_ _mauds.”_Western Stars.”_Western 8tars.”_City.”_ Would you feel grateful if, your last, a you favorable audience reaction to an Troy. gasping lifeguard pulled Irene”Dunne and Irene Dunne and Irene Dunne and Irene Dunne and Irene Dunne and Merle Oberon. Dennis Merle Oberon. Dennis to safety? nmuabbauur Cary Grant in Cary Grant in Cary Grant in Cary Grant in Cary Grant in Morgan. ‘Affection- Morgan. AfTection- tease from a theater ** imaginary strip ‘'How about the real thing?" but 18th and Columbia Rd. “Penny Serenade.'* Penny Serenade.'* “Penny Serenade "Penny Serenade.” "Penny Yours.” Maybe, Movie Actor Ronald Reagan won't take any bets. -

SCRAPBOOK of MOVIE STARS from the SILENT FILM and Early TALKIES Era

CINEMA Sanctuary Books 790 - Madison Ave - Suite 604 212 -861- 1055 New York, NY 10065 [email protected] Open by appointment www.sanctuaryrarebooks.com Featured Items THE FIRST 75 ISSUES OF FILM CULTURE Mekas, Jonas (ed.). Film Culture. [The First 75 Issues, A Near Complete Run of "Film Culture" Magazine, 1955-1985.] Mekas has been called “the Godfather of American avant-garde cinema.” He founded Film Culture with his brother, Adolfas Mekas, and covered therein a bastion of avant-garde and experimental cinema. The much acclaimed, and justly famous, journal features contributions from Rudolf Arnheim, Peter Bogdanovich, Stan Brakhage, Arlene Croce, Manny Farber, David Ehrenstein, John Fles, DeeDee Halleck, Gerard Malanga, Gregory Markopoulos, Annette Michelson, Hans Richter, Andrew Sarris, Parker Tyler, Andy Warhol, Orson Welles, and many more. The first 75 issues are collected here. Published from 1955-1985 in a range of sizes and designs, our volumes are all in very good to fine condition. Many notable issues, among them, those designed by Lithuanian Fluxus artist, George Macunias. $6,000 SCRAPBOOK of MOVIE STARS from the SILENT FILM and early TALKIES era. Staple-bound heavy cardstock wraps with tipped on photo- illustration of Mae McAvoy, with her name handwritten beneath; pp. 28, each with tipped-on and hand-labeled film stills and photographic images of celebrities, most with tissue guards. Front cover a bit sunned, lightly chipped along the edges; internally bright and clean, remarkably tidy in its layout and preservation. A collection of 110 images of actors from the silent film and early talkies era, including Inga Tidblad, Mona Martensson, Corinne Griffith, Milton Sills, Norma Talmadge, Colleen Moore, Charlie Chaplin, Lillian Gish, and many more.