Social Isolation in Mid Hampshire 12

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winchester Traveller DPD : Reports to Cabinet (LP) Committee Meeting

Winchester Traveller DPD : Reports to Cabinet (LP) Committee Meeting reference and date Key matters considered CAB2837(LP) 5 October 2016 A programme for preparation of the DPD was reported given the accommodation needs were to be established in LPP2, through a proposed main modification. Presentation of Initial findings on two key evidence reports – site assessments and gypsy and traveller accommodation needs assessment which had recently been completed. CAB2904(LP) 27 February 2017 Further details on the timescale for the preparation of the DPD with LP2 being declared ‘sound’ in January 2017. Feedback on representations received to the ‘commencement notice’ issued during October – December 2016. CAB2947(LP) 30 June 2017 Feedback on initial options consultation held during March – May 2017. Cabinet 5 July 2017 Approval of draft DPD for consultation under Regulation 18 – agreement to explore options to consider the purchasing of land/premises to accommodate the shortfall in provision of sites for travelling showpeople CAB2965(LP) 4 December 2017 Feedback on representations received under Regulation 18 and conclusions of Cabinet 6 December 2017 land search process which did not reveal any suitable sites for purchase. Council 10 January 2018 Approval of amended DPD to publish under Regulation 19 and subsequent submission for examination. CAB2837(LP) FOR DECISION WARD(S): ALL CABINET (LOCAL PLAN) COMMITTEE 5 October 2016 GYPSY AND TRAVELLER NEEDS / SITE ALLOCATIONS DEVELOPMENT PLAN DOCUMENT REPORT OF HEAD OF STRATEGIC PLANNING Contact Officer: -

Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation Sincs Hampshire.Pdf

Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation (SINCs) within Hampshire © Hampshire Biodiversity Information Centre No part of this documentHBIC may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recoding or otherwise without the prior permission of the Hampshire Biodiversity Information Centre Central Grid SINC Ref District SINC Name Ref. SINC Criteria Area (ha) BD0001 Basingstoke & Deane Straits Copse, St. Mary Bourne SU38905040 1A 2.14 BD0002 Basingstoke & Deane Lee's Wood SU39005080 1A 1.99 BD0003 Basingstoke & Deane Great Wallop Hill Copse SU39005200 1A/1B 21.07 BD0004 Basingstoke & Deane Hackwood Copse SU39504950 1A 11.74 BD0005 Basingstoke & Deane Stokehill Farm Down SU39605130 2A 4.02 BD0006 Basingstoke & Deane Juniper Rough SU39605289 2D 1.16 BD0007 Basingstoke & Deane Leafy Grove Copse SU39685080 1A 1.83 BD0008 Basingstoke & Deane Trinley Wood SU39804900 1A 6.58 BD0009 Basingstoke & Deane East Woodhay Down SU39806040 2A 29.57 BD0010 Basingstoke & Deane Ten Acre Brow (East) SU39965580 1A 0.55 BD0011 Basingstoke & Deane Berries Copse SU40106240 1A 2.93 BD0012 Basingstoke & Deane Sidley Wood North SU40305590 1A 3.63 BD0013 Basingstoke & Deane The Oaks Grassland SU40405920 2A 1.12 BD0014 Basingstoke & Deane Sidley Wood South SU40505520 1B 1.87 BD0015 Basingstoke & Deane West Of Codley Copse SU40505680 2D/6A 0.68 BD0016 Basingstoke & Deane Hitchen Copse SU40505850 1A 13.91 BD0017 Basingstoke & Deane Pilot Hill: Field To The South-East SU40505900 2A/6A 4.62 -

Burley Denny Lodge Hursley Overton Minstead Binsted Beaulieu Fawley

Mortimer Newtown West End East Ashford Hill with Headley Stratfield Saye Silchester Bramshill Woodhay Tadley Stratfield TurgisHeckfield Eversley Highclere Pamber Yateley Burghclere Kingsclere Baughurst BramleyHartley Wespall Mattingley Linkenholt Ecchinswell, Sydmonton Blackwater Faccombe Sherfield on Loddon and Hawley Vernhams and Bishops Green Sherborne St. John Hartley Wintney Ashmansworth Monk Sherborne Sherfield Park Rotherwick Dean Elvetham Heath Litchfield and Woodcott Hannington Chineham Wootton St. Lawrence Hook Fleet Hurstbourne Tarrant Rooksdown Newnham Winchfield Old Basing and Lychpit Church Crookham Dogmersfield Crookham Tangley St. Mary Bourne Mapledurwell and Up Nately Oakley Greywell Village Whitchurch Deane Odiham Ewshot Smannell Overton Winslade Appleshaw Enham Alamein Cliddesden Tunworth Penton Grafton Upton Grey Crondall Kimpton Steventon Charlton Hurstbourne Priors Farleigh Wallop Weston Corbett Fyfield Andover Laverstoke North Waltham Long Sutton Penton Mewsey Ellisfield South Warnborough Shipton Bellinger Dummer Herriard Weston Patrick Bentley Thruxton Amport Longparish Nutley Monxton Popham Froyle Upper Clatford Quarley Abbotts Ann Bradley Lasham Bullington Shalden Grateley Goodworth Clatford Preston Candover Wherwell Binsted Barton Stacey Micheldever Bentworth Wonston Candovers Wield Alton Over Wallop Beech Chilbolton Kingsley Longstock Northington Worldham Leckford Chawton Headley Nether Wallop Medstead South Wonston Old Alresford Lindford Stockbridge Crawley Farringdon Grayshott Bighton Little Somborne Kings -

01962 732079 Email

New Alresford Town Council Alresford Recreation Centre, The Avenue, Alresford, Hants, SO24 9EP Tel: 01962 732079 Email: [email protected] Website: www.newalresford-tc.gov.uk Minutes of the Planning Committee meeting held on Tuesday 4th June 2019 at Alresford Recreation Centre, Alresford, SO24 9EP, commencing at 6.00pm. In attendance Apologies Absent Cllr Gordon-Smith Cllr S Holmes Cllr Sprott Cllr Byrne Cllr B Jeffs Cllr K Divall Cllr S Evans ALSO PRESENT: Committee Clerk-Frances Simpson Town Clerk- Marcia Phillibert Clerk’s Assistant- Liz Jenkinson P19/056 To receive and accept apologies for absence Apologies of absence were received from Cllrs Jeffs & Holmes due to prior engagements. P19/057 To elect Chair of New Alresford Planning Committee for municipal year 2019/20 The Planning Committee proposed Cllr Gordon-Smith as returning Chairman. Proposed: Cllr Sprott Seconded: Cllr Byrne All agreed. P19/058 To elect Vice Chair of New Alresford Planning committee for municipal year 2019/20 The Planning committee proposed Cllr Jeffs to be vice-chair. Proposed: Cllr Gordon-Smith Seconded: Cllr Sprott. All agreed P19/059 To receive Declarations of Disclosable Pecuniary and Non-Pecuniary interests on items on the agenda. Cllr Sprott declared a private & personal interest in application 19/00946/HOU Holmleigh, Winchester Road, SO24 9EZ P19/060 To approve dispensations for Disclosable Pecuniary Interests under Section 33 of the Localism Act 2011. The Clerk advised nothing received for this meeting. P19/061 Public participation for fifteen minutes to allow members of the public present to raise questions on issues not included in the agenda. -

Bishops Sutton | Alresford

3 Park View | Bishops Sutton | Alresford 3 Park View Bishops Sutton | Alresford Hampshire | SO24 0AJ Guide Price £325,000 Character and Modern Features Re-fitted Kitchen (4 years ago) Modern Bathroom Two good sized Bedrooms Private Rear Garden Village Location This well presented character cottage has been up-graded to provide modern fittings, yet retains some of the period features including Victorian style fireplaces. Set within the popular semi-rural village of Bishops Sutton, on a bus route between Alton and Winchester. The property has had the benefit of an extended and re- fitted kitchen and from the original conversion of the cottages has a flying freehold, with the original loft belonging to the adjoining cottage. On entering the property via the covered porch you step into the sitting/dining room (previously two rooms) with a central staircase leading to the first floor, thus still providing the property with a defined area for a dining table. This in turn leads through to the kitchen which has ample storage and a door to outside. The first floor has two good size bedrooms and a bathroom with modern fittings. Outside: To the rear of the property there is a shared patio area with steps up to a pathway that leads to the private rear garden, mainly laid to lawn with mature hedging. The village of Bishops Sutton is located just 1.5 miles from the beautiful market town of Alresford with its varied mix of independent shops and businesses. There is a bus service from Bishops Sutton to Alresford, Winchester, Alton and Petersfield. -

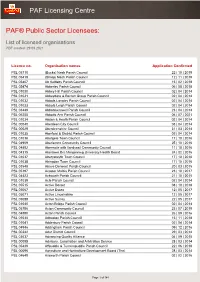

List of Licensed Organisations PDF Created: 29 09 2021

PAF Licensing Centre PAF® Public Sector Licensees: List of licensed organisations PDF created: 29 09 2021 Licence no. Organisation names Application Confirmed PSL 05710 (Bucks) Nash Parish Council 22 | 10 | 2019 PSL 05419 (Shrop) Nash Parish Council 12 | 11 | 2019 PSL 05407 Ab Kettleby Parish Council 15 | 02 | 2018 PSL 05474 Abberley Parish Council 06 | 08 | 2018 PSL 01030 Abbey Hill Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 01031 Abbeydore & Bacton Group Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 01032 Abbots Langley Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 01033 Abbots Leigh Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 03449 Abbotskerswell Parish Council 23 | 04 | 2014 PSL 06255 Abbotts Ann Parish Council 06 | 07 | 2021 PSL 01034 Abdon & Heath Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 00040 Aberdeen City Council 03 | 04 | 2014 PSL 00029 Aberdeenshire Council 31 | 03 | 2014 PSL 01035 Aberford & District Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 01036 Abergele Town Council 17 | 10 | 2016 PSL 04909 Aberlemno Community Council 25 | 10 | 2016 PSL 04892 Abermule with llandyssil Community Council 11 | 10 | 2016 PSL 04315 Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Board 24 | 02 | 2016 PSL 01037 Aberystwyth Town Council 17 | 10 | 2016 PSL 01038 Abingdon Town Council 17 | 10 | 2016 PSL 03548 Above Derwent Parish Council 20 | 03 | 2015 PSL 05197 Acaster Malbis Parish Council 23 | 10 | 2017 PSL 04423 Ackworth Parish Council 21 | 10 | 2015 PSL 01039 Acle Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 05515 Active Dorset 08 | 10 | 2018 PSL 05067 Active Essex 12 | 05 | 2017 PSL 05071 Active Lincolnshire 12 | 05 -

Act 1990 LIST of NEW PLANNING and OTHER

Town and Country Planning Acts 1990 Planning (Listed Building and Conservation Area) Act 1990 LIST OF NEW PLANNING AND OTHER APPLICATIONS, RECEIVED AND VALID IN PARISH/TOWN WARD ORDER WEEKLY LIST AS AT 08 January 2012 For Guidance 1 Those applications which have a star by them are FOR INFORMATION PURPOSES ONLY. Please see over for a list and description of application types. 2 If the Grid Reference is blank, this is because it is a property which is in the process of being entered on the Property Database for the District. 3 The Conservation Area only appears where the application is known to be in a Conservation Area. 4 Where the application has not been allocated to a case officer, “Team Manager “ for the relevant area appears instead. 5 The Publicity Period is 21 days after the Site Notice Date or 21 days after a Press Advert date, where this has been made, whichever is the later. Applications may be determined after this date. If you require any further information, please enquire at Main Reception, City Offices, Colebrook Street, Winchester, SO23 9LJ quoting the Case Number. We will then be able to give you the current status of the application. We are open Monday to Thursday 8.30am - 5.00pm, Fridays 8.30am - 4.30pm, excluding Bank and Public Holidays. Page 1 APPLICATION CODES AND DESCRIPTION AVC Full Advert Consent AVT Temporary Advert Consent (non-standard time limit) AGA Agricultural Application APN Agricultural Prior Notification CER Certificate of Alternative Use CHU Change of Use DEC Demolition Consultation EUC Established -

Division Arrangements for Hartley Wintney & Yateley West

Mortimer West End Silchester Stratfield Saye Bramshill Heckfield Eversley Yateley Stratfield Turgis Calleva Pamber Bramley Mattingley Hartley Wespall Hartley Wintney & Yateley West Yateley East & Blackwater Blackwater and Hawley Hartley Wintney Farnborough North Sherborne St. John Sherfield on Loddon Rotherwick Farnborough West Elvetham Heath Chineham Fleet Hook Fleet Town Basingstoke North Winchfield Farnborough South Newnham Old Basing and Lychpit Loddon Church Crookham Basingstoke Central Odiham & Hook Dogmersfield Crookham Village Mapledurwell and Up Nately Church Crookham & Ewshot Greywell Aldershot North Basingstoke South East Odiham Ewshot Winslade Aldershot South Candovers, Oakley & Overton Crondall Cliddesden South Warnborough Tunworth Upton Grey Farleigh Wallop Long Sutton County Division Parishes 0 0.75 1.5 3 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016 Hartley Wintney & Yateley West © Crown copyright and database rights 2016 OSGD Division Arrangements for 100049926 2016 Emsworth & St Faiths North West Havant Hayling Island County Division Parishes 0 0.4 0.8 1.6 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016 Hayling Island © Crown copyright and database rights 2016 OSGD Division Arrangements for 100049926 2016 Durley Bishops Waltham West End & Horton Heath West End Botley & Hedge End North Hedge End Curdridge Hedge End & West End South Meon Valley Botley Bursledon Hound Hamble Fareham Sarisbury Whiteley County Division Parishes 0 0.275 0.55 1.1 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown -

1881 Census for Weeke, Hants 2 Extracted from the Enumerators Books by Barrie Brinkman 2007 3 No

AB C D E FGHIJ KLM 1 1881 Census for Weeke, Hants 2 Extracted from the enumerators books by Barrie Brinkman 2007 3 No. Page Address CName SNAME Status M S A Occupation E H Where born 4 1 RG11/1231/65/1 33 Andover Rd James LEGGATT Head M M 34 Under Gardener (D) Winchester, Hampshire 5 ,Weeke Elizabeth LEGGATT Wife M F 40 Worthy, Hampshire 6 William CROOK Son S M 23 Labourer Worthy, Hampshire 7 David CROOK Son S M 22 Fettler Week, Hampshire 8 Harry CROOK Son S M 15 Errand Boy Week, Hampshire 9 Mary CROOK Dau S F 13 Scholar Week, Hampshire 10 John CROOK Son S M 9 Scholar Week, Hampshire 11 2 34 Andover Rd Henry WEBB Head M M 30 Bricklayer Barton Stacey, Hants 12 ,Weeke Jemima WEBB Wife M F 34 Whichford, Warwick 13 Elizabeth WEBB Dau S F 2 Winchester, Hampshire 14 Ellen WEBB Dau S F 6m Winchester, Hampshire 15 3 35 Andover Rd Fredrick CUELL Head M M 40 Gardener (7) Crawley, Hampshire 16 ,Weeke Jane CUELL Wife M F 41 West Shepstone, 17 Harriet CUELL Dau S F 14 Domestic Servant Winchester, Hampshire 18 Mary CUELL Dau S F 12 Domestic Servant Winchester, Hampshire 19 Edith CUELL Dau S F 9 Scholar Winchester, Hampshire 20 Annie CUELL Dau S F 6 Scholar Winchester, Hampshire 21 Ernest CUELL Son S M 4 Winchester, Hampshire 22 Herbert CUELL Son S M 1 Winchester, Hampshire 23 4 36 Andover Rd George HILING Head M M 29 Butler Barford, Norfolk 24 ,Weeke Agnes HILING Wife M F 26 Redbridge, Hampshire 25 5 RG11/1231/65/2 37 Andover Rd John BROWN Head M M 47 Gardener Chelsea Ireland 26 ,Weeke Bridget BROWN Wife M F 26 Laundress Ireland 27 William BROWN Son -

Impact Report Bishops Sutton

Carbon Footprint Report: Bishops Sutton 02/07/2021 1. Your Footprint Report Welcome to your community’s carbon footprint report! This report tells you about your community’s carbon1 footprint – both the scale of emissions and the main ‘activities’ responsible for the emissions. This information comes from Impact – an online civil parish-level carbon emissions estimator: https://impact- tool.org.uk/ Your report also shows how your community’s footprint compares with the district average and the national average. It shows your community’s territorial and consumption footprints. There are two ways of viewing a community’s carbon footprint – territorial-based or consumption-based. A community’s territorial footprint considers the emissions that are produced within their parish boundary – such as from heating buildings, transport, industry, and agriculture – regardless of whether the residents within the community are engaged in or demand those practices. For example, imagine there is a factory in that community and much of what the factory produces is ‘exported’ from that community and consumed elsewhere rather than locally; the factory’s emissions would still be counted as part of that community’s territorial footprint. A territorial footprint is largely created by taking national and local authority datasets and cutting these down to the local geography in as accurate a way as possible. A community’s consumption footprint captures all the emissions produced as a result of the ‘activities’ that the community’s residents engage in, regardless of where geographically they occur – for example, emissions resulting from the food they eat, the clothes and household items they buy, the leisure activities they engage in, their travel behaviours, and the heating of their homes. -

Winchester As Well As Towns Such As Stockbridge, Alresford and Petersfi Eld, Hampshire Offers a Wonderful Variety of Destinations

Local Overview Local area overview The numbers Hampshire The area % Hampshire’s appeal to property purchasers continues 94 to grow as more and more people move from the capital The average we achieve to the county. From The South Downs National Park of guide price to the east and the New Forest to the west, The Solent coastline to the city of Winchester as well as towns such as Stockbridge, Alresford and Petersfi eld, Hampshire offers a wonderful variety of destinations. Not only does % it boast beautiful countryside but also excellent schools, 73 facilities and leisure activities. And of course the fast of our properties are priced and regular train services to London have always been at under £1,000,000 a draw for those moving out of the capital but needing to commute. In the past 12 months we’ve helped people sell and buy a wide range of different homes in Hampshire, from thatched cottages and land with planning permission, % to village houses of all styles. 85 of our buyers come from Our approach is uniquely powerful in that we pool out of the area the experience and expertise of our Winchester, Basingstoke, Hungerford and Haslemere teams. If you’re selling, this enables you to reach the maximum number of the right buyers – we also have our 29 London offi ces, broadening our reach to include the ever-increasing number of London buyers. If you’re looking to buy, it means you can reap the rewards of our genuinely encyclopedic local knowledge. Trust and integrity at every level Recently Currently Sold For Sale Since the election, buyers and sellers alike have swung into action, and with From pretty village houses, thatched rural cottages to more contemporary living, interest rates at record lows, demand is soaring. -

ALRESFORD SHOW by Robert Hedges "A Delightful Little Country Show," Remarked a Cattle Judge on One Occasion, "And

ALRESFORD SHOW By Robert Hedges "A delightful little country show," remarked a cattle judge on one occasion, "and run by such pleasant people!" The sense of enjoyment and success implicit in this spontaneous reaction was engendered in 1908 and has been fostered by several generations of presidents, officers and committee members ever since. As the farming year moves almost imperceptibly through changing scenes of work and weather to its culmination in the rewards of maturity and harvest, so the Alresford Shaw has developed through periods of fluctuating fortunes to its high level of excellence under enlightened management - at the same time cautious and imaginative, conservative and progressive - that has nursed it gently along from year to year, absorbing the pressures of scientific advancement, government policy and popular demand and somehow contriving to present annually a charming, traditional picture of Hampshire country life at its civilised best. Shows can vary in size from the man who humiliates his fellow gardeners by displaying an enormous potato in the local bar to the bewildering magnitude of a great national event. The Alresford Show has grown over the years and has now probably reached its optimum. But how did it start? Well, it was during the week when the suffragette Mrs. Parkhurst appeared at Bow Street on a charge of incitement to "rush" the Commons; when John Lee was brought before the Alresford Bench, charged with begging on Pound Hill; and when the Labour-Liberal candidate for the East Hants Division faced a hostile audience at Old Alresford School. Mr. T. C. Hankin, the landlord of the Swan Hotel (but soon to start the family motorcar business), was serving whisky at 2d a tot and beer at 2d a pint to a special group of gentlemen seated before a log fire.