Avalanche Accidents in Canada Volume 5 1996-2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Road Biking Guide

SUGGESTED ITINERARIES QUICK TIP: Ride your bike before 10 a.m. and after 5 p.m. to avoid traffic congestion. ARK JASPER NATIONAL P SHORT RIDES HALF DAY PYRAMID LAKE (MAP A) - Take the beautiful ride THE FALLS LOOP (MAP A) - Head south on the ROAD BIKING to Pyramid Lake with stunning views of Pyramid famous Icefields Parkway. Take a right onto the Mountain at the top. Distance: 14 km return. 93A and head for Athabasca Falls. Loop back north GUIDE Elevation gain: 100 m. onto Highway 93 and enjoy the views back home. Distance: 63 km return. Elevation gain: 210 m. WHISTLERS ROAD (MAP A) - Work up a sweat with a short but swift 8 km climb up to the base MARMOT ROAD (MAP A) - Head south on the of the Jasper Skytram. Go for a ride up the tram famous Icefields Parkway, take a right onto 93A and or just turn back and go for a quick rip down to head uphill until you reach the Marmot Road. Take a town. Distance: 16.5 km return. right up this road to the base of the ski hill then turn Elevation gain: 210 m. back and enjoy the cruise home. Distance: 38 km. Elevation gain: 603 m. FULL DAY MALIGNE ROAD (MAP A) - From town, head east on Highway 16 for the Moberly Bridge, then follow the signs for Maligne Lake Road. Gear down and get ready to roll 32 km to spectacular Maligne Lake. Once at the top, take in the view and prepare to turn back and rip home. -

Field Trip Guide Soils and Landscapes of the Front Ranges

1 Field Trip Guide Soils and Landscapes of the Front Ranges, Foothills, and Great Plains Canadian Society of Soil Science Annual Meeting, Banff, Alberta May 2014 Field trip leaders: Dan Pennock (U. of Saskatchewan) and Paul Sanborn (U. Northern British Columbia) Field Guide Compiled by: Dan and Lea Pennock This Guidebook could be referenced as: Pennock D. and L. Pennock. 2014. Soils and Landscapes of the Front Ranges, Foothills, and Great Plains. Field Trip Guide. Canadian Society of Soil Science Annual Meeting, Banff, Alberta May 2014. 18 p. 2 3 Banff Park In the fall of 1883, three Canadian Pacific Railway construction workers stumbled across a cave containing hot springs on the eastern slopes of Alberta's Rocky Mountains. From that humble beginning was born Banff National Park, Canada's first national park and the world's third. Spanning 6,641 square kilometres (2,564 square miles) of valleys, mountains, glaciers, forests, meadows and rivers, Banff National Park is one of the world's premier destination spots. In Banff’s early years, The Canadian Pacific Railway built the Banff Springs Hotel and Chateau Lake Louise, and attracted tourists through extensive advertising. In the early 20th century, roads were built in Banff, at times by war internees, and through Great Depression-era public works projects. Since the 1960s, park accommodations have been open all year, with annual tourism visits to Banff increasing to over 5 million in the 1990s. Millions more pass through the park on the Trans-Canada Highway. As Banff is one of the world's most visited national parks, the health of its ecosystem has been threatened. -

Day Hiking Lake Louise, Castle Junction and Icefields Parkway Areas

CASTLE JUNCTION AREA ICEFIELDS PARKWAY AREA LAKE LOUISE AREA PLAN AHEAD AND PREPARE Remember, you are responsible for your own safety. 1 7 14 Castle Lookout Bow Summit Lookout Wilcox Pass MORAINE LAKE AREA • Get advice from a Parks Canada Visitor Centre. Day Hiking 3.7 km one way; 520 m elevation gain; 3 to 4 hour round trip 2.9 km one way; 245 m elevation gain; 2.5 hour round trip 4 km one way; 335 m elevation gain; 3 to 3.5 hour round trip • Study trail descriptions and maps before starting. Trailhead: 5 km west of Castle Junction on the Bow Valley Parkway Trailhead: Highway 93 North, 40 km north of the Lake Louise junction, Trailhead: Highway 93 North, 47 km north of Saskatchewan Crossing, • Check the weather forecast and current trail conditions. (Highway 1A). at the Peyto Lake parking lot. or 3 km south of the Icefield Centre at the entrance to the Wilcox Creek Trailheads: drive 14 km from Lake Louise along the Moraine Lake Road. • Choose a trail suitable for the least experienced member in Lake Louise, Castle Junction campground in Jasper National Park. Consolation Lake Trailhead: start at the bridge near the Rockpile at your group. In the mid-20th century, Banff erected numerous fire towers From the highest point on the Icefields Parkway (2070 m), Moraine Lake. Pack adequate food, water, clothing, maps and gear. and Icefields Parkway Areas where spotters could detect flames from afar. The Castle Lookout hike beyond the Peyto Lake Viewpoint on the upper self-guided • Rise quickly above treeline to the expansive meadows of this All other trails: begin just beyond the Moraine Lake Lodge Carry a first aid kit and bear spray. -

Highway 3: Transportation Mitigation for Wildlife and Connectivity in the Crown of the Continent Ecosystem

Highway 3: Transportation Mitigation for Wildlife and Connectivity May 2010 Prepared with the: support of: Galvin Family Fund Kayak Foundation HIGHWAY 3: TRANSPORTATION MITIGATION FOR WILDLIFE AND CONNECTIVITY IN THE CROWN OF THE CONTINENT ECOSYSTEM Final Report May 2010 Prepared by: Anthony Clevenger, PhD Western Transportation Institute, Montana State University Clayton Apps, PhD, Aspen Wildlife Research Tracy Lee, MSc, Miistakis Institute, University of Calgary Mike Quinn, PhD, Miistakis Institute, University of Calgary Dale Paton, Graduate Student, University of Calgary Dave Poulton, LLB, LLM, Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative Robert Ament, M Sc, Western Transportation Institute, Montana State University TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables .....................................................................................................................................................iv List of Figures.....................................................................................................................................................v Executive Summary .........................................................................................................................................vi Introduction........................................................................................................................................................1 Background........................................................................................................................................................3 -

Mapping Recreational Trails Withing the Lower Seymour Conservation

Final Project Report Mapping Recreational Trails Within The Lower Seymour Conservation Reserve For: Heidi Walsh April 2001 From: Tony Botica Patrick Kaiser Mark McGough Table of Contents Summary…………………………………………..……………………………………………………..1 Introduction…………………………………………………………..…………………………………..2 Procedure………………………………………………………………………………..……………….4 Results………………………………………………..…………………………………………………..7 Problems………………………………………………………………….……………………………..11 Conclusion…...…………………………………………………………………………………………13 List of Appendices: Appendix 1: Access Road………………………………………………………………………………14 Appendix 2: Baselines 1,2,3……………………………………………………………………………17 Appendix 3: Blair Range………………………………………………………………………………..33 Appendix 4: Bottle Top…………………………………………………………………………………37 Appendix 5: CBC Trail…………………………………………………………………………………43 Appendix 6: Corkscrew Connector…………………………………………………………………..…90 Appendix 7: Corkscrew………………………………………………………………………………...93 Appendix 8: Cut-off Trail……………………………………………………………………………..102 Appendix 9: Dales Trail……………………………………………………………………………….106 Appendix 10: Dales/Blair Range Connector…………………………………………………………..120 Appendix 11: Fork Connector…………………………………………………………………………122 Appendix 12: Incline…………………………………………………………………………………..125 Appendix 13: Lizzie Lake Loop………………………………………………………………………130 Appendix 14: Mystery Creek………………………………………………………………………….134 Appendix 15: Mystery Falls…………………………………………………………………………...155 Appendix 16: Mystery Creek Fork……………………………………………………………………160 Appendix 17: Mushroom Lot………………………………………………………………………….164 Appendix 18: Mushroom Path………………………………………………………………………...167 -

Self-Guiding Geology Tour of Stanley Park

Page 1 of 30 Self-guiding geology tour of Stanley Park Points of geological interest along the sea-wall between Ferguson Point & Prospect Point, Stanley Park, a distance of approximately 2km. (Terms in bold are defined in the glossary) David L. Cook P.Eng; FGAC. Introduction:- Geomorphologically Stanley Park is a type of hill called a cuesta (Figure 1), one of many in the Fraser Valley which would have formed islands when the sea level was higher e.g. 7000 years ago. The surfaces of the cuestas in the Fraser valley slope up to the north 10° to 15° but approximately 40 Mya (which is the convention for “million years ago” not to be confused with Ma which is the convention for “million years”) were part of a flat, eroded peneplain now raised on its north side because of uplift of the Coast Range due to plate tectonics (Eisbacher 1977) (Figure 2). Cuestas form because they have some feature which resists erosion such as a bastion of resistant rock (e.g. volcanic rock in the case of Stanley Park, Sentinel Hill, Little Mountain at Queen Elizabeth Park, Silverdale Hill and Grant Hill or a bed of conglomerate such as Burnaby Mountain). Figure 1: Stanley Park showing its cuesta form with Burnaby Mountain, also a cuesta, in the background. Page 2 of 30 Figure 2: About 40 million years ago the Coast Mountains began to rise from a flat plain (peneplain). The peneplain is now elevated, although somewhat eroded, to about 900 metres above sea level. The average annual rate of uplift over the 40 million years has therefore been approximately 0.02 mm. -

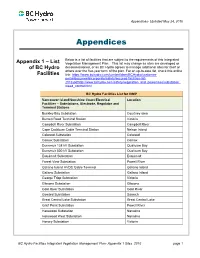

Appendices- Updated May 24, 2016

Appendices- Updated May 24, 2016 Appendices Below is a list of facilities that are subject to the requirements of this Integrated Appendix 1 – List Vegetation Management Plan. This list may change as sites are developed or of BC Hydro decommissioned, or as BC Hydro agrees to manage additional sites for itself or others over the five-year term of the plan. For an up-to-date list, check this online Facilities link: https://www.bchydro.com/content/dam/BCHydro/customer- portal/documents/corporate/safety/secured-facilities-list- 2013.pdfhttp://www.bchydro.com/safety/vegetation_and_powerlines/substation_ weed_control.html. BC Hydro Facilities List for IVMP Vancouver Island/Sunshine Coast Electrical Location Facilities – Substations, Electrode, Regulator and Terminal Stations Buckley Bay Substation Courtney area Burnett Road Terminal Station Victoria Campbell River Substation Campbell River Cape Cockburn Cable Terminal Station Nelson Island Colwood Substation Colwood Comox Substation Comox Dunsmuir 138 kV Substation Qualicum Bay Dunsmuir 500 kV Substation Qualicum Bay Esquimalt Substation Esquimalt Forest View Substation Powell River Galiano Island HVDC Cable Terminal Galiano Island Galiano Substation Galiano Island George Tripp Substation Victoria Gibsons Substation Gibsons Gold River Substation Gold River Goward Substation Saanich Great Central Lake Substation Great Central Lake Grief Point Substation Powell River Harewood Substation Nanaimo Harewood West Substation Nanaimo Horsey Substation Victoria BC Hydro Facilities Integrated Vegetation -

Mountain Ear MONTHLY NEWSLETTER of the ROCKY MOUNTAINEERS

Mountain Ear MONTHLY NEWSLETTER OF THE ROCKY MOUNTAINEERS wandMeetings are held on the second Wednesday of each month at 7:30 in the County Commissioner's meeting room on the second floor of the Armex (new portion) ofthe thesoula County Courthouse. Enter the building through the north door. 'Ihis month's meeting will be held on Wednesday, November 9, , i 111 Paul Jason will present a slide show entitled "Backcountry Skiing in Westem Montana, the Canadian Rockies, and the Tetons." Paul will show slides from the Bitterroots, Swans, and Mission Mountains as well as the Canadian Rockies and the Tetons, TRIPCATANTXR 11-13.. Wee day mmountainep-ing trip to 10,052-foot Mount Jackson in Glacier Park. The fmt day will be a pleasant hike/ski to Gunsight Lake where base camp will be made. ?he standard route up the peak is just a scramble, but with a heavy fresh snow cover, it should bi interesting, Other routes also exist. This will be an opportunity to experience some brisk weather in beautiful co~try.Depending on inmest and time ccmstraints,another location or a two-day trip may be substituted. Call Gerald Olbu at 549-4769 for more information, November Ski to 9351-foot St Mary's Peak in the Bitterroots near Florence, This will be a moderate ski trip, Most likely it will be possible to drive to the trailhead, so the trip will be about 4-5 miles and 2800 feet elevation gain to the peak. There is a lookout tower, open to the public, on the summit. -

February Newsletter

Winter continues to cover Kananaskis in a blanket of snow. Have you been out enjoying it? If You Admire the View, You Are a Friend Of Kananaskis For the rest of 2013, the Friends Newsletter will feature wildlife camera photographs from Kananaskis Country. The photos were provided by John Paczkowski, the Park Ecologist for Kananaskis Country. Many of the photographs are part of research programs in the various areas of Kananaskis. The one above is a cougar attempting to steal a beaver carcass hung in a tree. These carcasses are used to attract and photograph wolverines, and the barbed wire you see allows collection of hair samples for DNA identity testing. If you have not met John, you should. He has spoken at several Friends events, and has one of the best jobs in the world, tracking wildlife movements in and around K-Country. Beside which, John's a great guy and we thank him for his generosity in supplying these photos. Trail Care 2013 Update By Rosemary Power, Program CoOrdinator With the spring just around the corner, we are looking ahead to our 2013 Trail Care season with TransAlta as the title sponsor for this years program. Thanks to you, our hard working volunteers, we will be providing trail maintenance and construction in a wide variety of locations in and around Kananaskis Country. As in previous years, our main trail work days will be the second Saturday of each month but additional days, both weekday and weekend, will likely be created. Work usually ranges from pruning back bushes growing alongside the trail, through to digging drainage channels, sawing logs (by hand) and splitting rock or moving boulders. -

Ya Ha Tinda Elk Project Annual Report 2016-2017

Ya Ha Tinda Elk Project Annual Report 2016-2017 Ya Ha Tinda Elk Project Annual Report 2016 - 2017 Submitted to: Parks Canada, Alberta Environment and Parks & Project Stakeholders Prepared by: Hans Martin & Mark Hebblewhite University of Montana & Jodi Berg, Kara MacAulay, Mitchell Flowers, Eric Spilker, Evelyn Merrill University of Alberta 1 Ya Ha Tinda Elk Project Annual Report 2016-2017 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank Parks Canada staff Blair Fyten, Jesse, Whitington, David Gummer, and Bill Hunt for providing logistical and financial support, especially during the winter capture season. For their never-ending help, patience and understanding, we thank the Ya Ha Tinda ranch staff: Rick and Jean Smith, Rob Jennings, James Spidell and Tom McKenzie. Anne Hubbs (AB ESRD), Rachel Cook (NCASI), P.J. White (NPS), Bruce Johnson (OR DFW), Shannon Barber-Meyer (USGS), Simone Ciuti (U Alberta), and Holger Bohm (U Alberta) all provided helpful advice and discussions, and Dr. Todd Shury (Parks Canada), Dr. Geoff Skinner (Parks Canada), Dr. Asa Fahlman, Dr. Rob McCorkell (U Calgary), Dr. Bryan Macbeth, Mark Benson, Eric Knight, and Dr. Owen Smith (U Calgary) gave their time, expert knowledge, and assistance during winter captures. For guidance in dog training and for providing our project with great handlers and dogs, our appreciation goes to Julie Ubigau, Caleb Stanek, and Heath Smith from Conservation Canines. We also thank local residents, Alberta Trapper Association of Sundre and Friends of the Eastern Slopes Association for their interest in the project. University of Alberta staff, volunteers, and interns assisted for various lengths of time, in various tasks surrounding the calf captures, monitoring, and logistics. -

Ski Resorts (Canada)

SKI RESORTS (CANADA) Resource MAP LINK [email protected] ALBERTA • WinSport's Canada Olympic Park (1988 Winter Olympics • Canmore Nordic Centre (1988 Winter Olympics) • Canyon Ski Area - Red Deer • Castle Mountain Resort - Pincher Creek • Drumheller Valley Ski Club • Eastlink Park - Whitecourt, Alberta • Edmonton Ski Club • Fairview Ski Hill - Fairview • Fortress Mountain Resort - Kananaskis Country, Alberta between Calgary and Banff • Hidden Valley Ski Area - near Medicine Hat, located in the Cypress Hills Interprovincial Park in south-eastern Alberta • Innisfail Ski Hill - in Innisfail • Kinosoo Ridge Ski Resort - Cold Lake • Lake Louise Mountain Resort - Lake Louise in Banff National Park • Little Smokey Ski Area - Falher, Alberta • Marmot Basin - Jasper • Misery Mountain, Alberta - Peace River • Mount Norquay ski resort - Banff • Nakiska (1988 Winter Olympics) • Nitehawk Ski Area - Grande Prairie • Pass Powderkeg - Blairmore • Rabbit Hill Snow Resort - Leduc • Silver Summit - Edson • Snow Valley Ski Club - city of Edmonton • Sunridge Ski Area - city of Edmonton • Sunshine Village - Banff • Tawatinaw Valley Ski Club - Tawatinaw, Alberta • Valley Ski Club - Alliance, Alberta • Vista Ridge - in Fort McMurray • Whispering Pines ski resort - Worsley British Columbia Page 1 of 8 SKI RESORTS (CANADA) Resource MAP LINK [email protected] • HELI SKIING OPERATORS: • Bearpaw Heli • Bella Coola Heli Sports[2] • CMH Heli-Skiing & Summer Adventures[3] • Crescent Spur Heli[4] • Eagle Pass Heli[5] • Great Canadian Heliskiing[6] • James Orr Heliski[7] • Kingfisher Heli[8] • Last Frontier Heliskiing[9] • Mica Heliskiing Guides[10] • Mike Wiegele Helicopter Skiing[11] • Northern Escape Heli-skiing[12] • Powder Mountain Whistler • Purcell Heli[13] • RK Heliski[14] • Selkirk Tangiers Heli[15] • Silvertip Lodge Heli[16] • Skeena Heli[17] • Snowwater Heli[18] • Stellar Heliskiing[19] • Tyax Lodge & Heliskiing [20] • Whistler Heli[21] • White Wilderness Heli[22] • Apex Mountain Resort, Penticton • Bear Mountain Ski Hill, Dawson Creek • Big Bam Ski Hill, Fort St. -

Municipal Development Plan

Municipality of Crowsnest Pass MUNICIPAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN BYLAW NO. 1059, 2020 © 2021 Oldman River Regional Services Commission Prepared for the Municipality of Crowsnest Pass This document is protected by Copyright and Trademark and may not be reproduced or modified in any manner, or for any purpose, except by written permission of the Oldman River Regional Services Commission. This document has been prepared for the sole use of the Municipality addressed and the Oldman River Regional Services Commission. This disclaimer is attached to and forms part of the document. ii MUNICIPALITY OF CROWSNEST PASS BYLAW NO. 1059, 2020 MUNICIPAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN BYLAW BEING a bylaw of the Municipality of Crowsnest Pass, in the Province of Alberta, to adopt a new Municipal Development Plan for the municipality. AND WHEREAS section 632 of the Municipal Government Act requires all municipalities in the provinceto adopt a municipaldevelopment plan by bylaw; AND WHEREAS the purpose of the proposed Bylaw No. 1059, 2020 is to provide a comprehensive, long-range land use plan and development framework pursuant to the provisions outlined in the Act; AND WHEREAS the municipal council has requested the preparation of a long-range plan to fulfill the requirementsof the Act and provide for its consideration at a public hearing; NOW THEREFORE, under the authority and subject to the provisions of the Municipal Government Act, Revised Statutes of Alberta 2000, Chapter M-26, as amended, the Council of the Municipality of Crowsnest Pass in the province of Alberta duly assembled does hereby enact the following: 1. Bylaw No. 1059, 2020, being the new Municipal Development Plan Bylaw is hereby adopted.