On the Roles of Information in the Interaction of Agents in Markets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trustees Vote to Raise Tuition Beginning 1997-98 School Year

Volume 79 No. 83 £ Youngstown, OH Tuesday, May 6,1997 zzzzzzzzzzzzzz Trustees vote to raise tuition The new deep beginning 1997-98 school year relaxation • 3.9 increase will help cover higher faculty and staff wages - _ study technique Peggy Moore the tuition hike will go back to $4,001. Even with the increase, News Editor students in the form of a schol• YSU's cost remains less than from the arship fund to assist students that average. Far East. The YSU Board of Trustees with financial needs. Tuition for full-time out-of- approved a 3.9 percent in• Full-time tuition for Ohio stu• state students within a 100- crease in student tuition for the dents will jump $132 a year, mile radius of campus will in• 1997-98 school year. The in• from $3,366 to $3,498. This rep• crease $198, from $4,986 to TASHA CURTIS THEJAMBAR crease will go. toward offset• resents a nearly 60 percent in• $5,184. Other out-of-state stu• ill! Mike Welch, ting a $2.5 million increase in crease since 1990-91, when the dents will pay $279 more, with 19, next year's budget. annual cost was $2,190. tuition gowing from $7,002 to freshman, $7,281. The increase is just shy of Cochran said "Even with the realizing his the 4 percent tuition cap im• increase, YSU still remains the The tuition increase will go posed by the state and Gov. best educational value in the toward higher faculty and staff mid-term George Voinovich at all Ohio state." wages, which make up 52 per- started 15 state universities. -

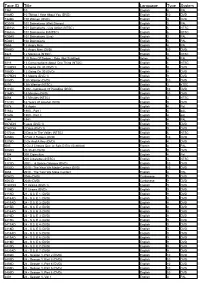

Tape ID Title Language Type System

Tape ID Title Language Type System 1361 10 English 4 PAL 1089D 10 Things I Hate About You (DVD) English 10 DVD 7326D 100 Women (DVD) English 9 DVD KD019 101 Dalmatians (Walt Disney) English 3 PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English 6 NTSC KD040 101 Dalmations (Live) English 3 PAL KD041 102 Dalmatians English 3 PAL 0665 12 Angry Men English 4 PAL 0044D 12 Angry Men (DVD) English 10 DVD 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English 3 NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian 4 PAL 6016 13 Conversations About One Thing (NTSC) English 1 NTSC 0189DN 13 Going On 30 (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 7080D 13 Going On 30 (DVD) English 9 DVD 0179DN 13 Moons (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 3050D 13th Warrior (DVD) English 10 DVD 6291 13th Warrior (NTSC) English 3 nTSC 5172D 1492 - Conquest Of Paradise (DVD) English 10 DVD 3165D 15 Minutes (DVD) English 10 DVD 6568 15 Minutes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 7122D 16 Years Of Alcohol (DVD) English 9 DVD 1078 18 Again English 4 Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English 4 pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English 4 pAL 1244 1941 English 4 PAL 0072DN 1Love (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0141DN 2 Days (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 3256D 2 Fast 2 Furious (DVD) English 10 DVD 5276D 2 Gs And A Key (DVD) English 4 DVD f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French 4 PAL X059D 20 30 40 (DVD) English 9 DVD 1304 200 Cigarettes English 4 Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 3172D 2001 - A Space Odyssey (DVD) English 10 DVD 3032D 2010 - The Year -

Tv Pg 5 09-02.Indd

The Goodland Star-News / Tuesday, September 2, 2008 5 Like puzzles? Then you’ll love sudoku. This mind-bending puzzle FUN BY THE NUM B ERS will have you hooked from the moment you square off, so sharpen your pencil and put your sudoku savvy to the test! Here’s How It Works: Sudoku puzzles are formatted as a 9x9 grid, broken down into nine 3x3 boxes. To solve a sudoku, the numbers 1 through 9 must fill each row, column and box. Each number can appear only once in each row, column and box. You can figure out the order in which the numbers will appear by using the numeric clues already provided in the boxes. The more numbers you name, the easier it gets to solve the puzzle! ANSWER TO TUESD A Y ’S TUESDAY EVENING SEPTEMBER 9, 2008 WEDNESDAY EVENING SEPTEMBER 10, 2008 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 ES E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone ES E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone Dog Bounty Dog Bounty Dog Bounty Dog Bnty Mindfreak Criss Angel: Criss Angel Criss Angel Dog Bounty Dog Bounty The First 48 Murder of a The First 48 (TVMA) (R) The Cleaner: Let It Ride The Cleaner: Let It Ride The First 48 Murder of a 36 47 A&E 36 47 A&E farmer. (TVMA) (R) (TV14) (N) (HD) (TV14) (R) (HD) farmer. (TVMA) (R) (R) (R) (R) (TVPG) (TVPG) Tronik (R) (R) (R) (R) Wife Swap: Supernanny: Martinez Primetime: Crime (N) KAKE News (:35) Nightline (:06) Jimmy Kimmel Live Wipeout Human Pinball; Wipeout Goofy Goggles. -

The BG News September 12, 1997

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 9-12-1997 The BG News September 12, 1997 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News September 12, 1997" (1997). BG News (Student Newspaper). 6203. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/6203 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Directory SPORTS OPINION ; TODAY Switchboard 372-2601 /P^ Classified Ads 372-6977 Women's Soccer Men's Soccer Display Ads 372-2605 Brandon Wray Editorial 372-6966 at Indiana vs. Dayton Sports 372-2602 takes on \UN-'\ /~oi . Entertainment 372-2603 7 p.m. Friday 3 p.m. Saturday fc 3 c Story Idea? Give us a call [The Falcons also take on Northern BGSU Soccer Classic cancelled; the Man hazy weekdays from I pjn. to 5 pm.,or Illinois at noon on Sunday Falcons to lace only Flyers e-mail: "[email protected]" High: 71 Low: 54 FRIDAY September 12,1997 Volume 84, Issue 12 The BG News Bowling Green, Ohio "Serving the Bowling Green community for over 75years" # Diana's flowers Battle of Ohio cleared away □ The mountains of tributes left for Diana are being removed by volunteers and used for charity. f BOWLING #. -

Gorinski2018.Pdf

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Automatic Movie Analysis and Summarisation Philip John Gorinski I V N E R U S E I T H Y T O H F G E R D I N B U Doctor of Philosophy Institute for Language, Cognition and Computation School of Informatics University of Edinburgh 2017 Abstract Automatic movie analysis is the task of employing Machine Learning methods to the field of screenplays, movie scripts, and motion pictures to facilitate or enable vari- ous tasks throughout the entirety of a movie’s life-cycle. From helping with making informed decisions about a new movie script with respect to aspects such as its origi- nality, similarity to other movies, or even commercial viability, all the way to offering consumers new and interesting ways of viewing the final movie, many stages in the life-cycle of a movie stand to benefit from Machine Learning techniques that promise to reduce human effort, time, or both. -

Feature Films for Education Collection

COMINGSOON! in partnership with FEATURE FILMS FOR EDUCATION COLLECTION Hundreds of full-length feature films for classroom use! This high-interest collection focuses on both current • Unlimited 24/7 access with and hard-to-find titles for educational instructional no hidden fees purposes, including literary adaptations, blockbusters, • Easy-to-use search feature classics, environmental titles, foreign films, social issues, • MARC records available animation studies, Academy Award® winners, and • Same-language subtitles more. The platform is easy to use and offers full public performance rights and copyright protection • Public performance rights for curriculum classroom screenings. • Full technical support Email us—we’ll let you know when it’s available! CALL: (800) 322-8755 [email protected] FAX: (646) 349-9687 www.Infobase.com • www.Films.com 0617 in partnership with COMING SOON! FEATURE FILMS FOR EDUCATION COLLECTION Here’s a sampling of the collection highlights: 12 Rounds Cocoon A Good Year Like Mike The Other Street Kings 12 Years a Slave The Comebacks The Grand Budapest Little Miss Sunshine Our Family Wedding Stuck on You 127 Hours Commando Hotel The Lodger (1944) Out to Sea The Sun Also Rises 28 Days Later Conviction (2010) Grand Canyon Lola Versus The Ox-Bow Incident Sunrise The Grapes of Wrath 500 Days of Summer Cool Dry Place The Longest Day The Paper Chase Sunshine Great Expectations The Abyss Courage under Fire Looking for Richard Parental Guidance Suspiria The Great White Hope Adam Crazy Heart Lucas Pathfinder Taken -

Hotel Rwanda Production Notes

When the world closed its eyes, he opened his arms… PRODUCTION NOTES Ten years ago, some of the worst atrocities of the twentieth century took place in the central African nation of Rwanda – yet in an era of high-speed communication and round-the- clock news, the events went almost unnoticed by the rest of the world. Over one hundred days, almost one million people were brutally murdered by their own countrymen. In the midst of this genocide, one ordinary man, a hotel manager named Paul Rusesabagina – inspired by his love for his family and his humanity – summoned extraordinary courage and saved the lives of 1268 refugees by hiding them inside the Milles Collines hotel in Kigali. Hotel Rwanda is Paul’s remarkable story. United Artists is proud to present Don Cheadle, Sophie Okonedo, Joaquin Phoenix, and Nick Nolte in Hotel Rwanda, produced in association with Lions Gate Entertainment, a South Africa/United Kingdom/Italy co-production in association with The Industrial Development Corporation of South Africa, a Miracle Pictures/Seamus production produced in association with Inside Track. Directed by Terry George from a script by Keir Pearson & Terry George, Hotel Rwanda was produced by A. Kitman Ho and Terry George; executive produced by Hal Sadoff, Martin F. Katz, Duncan Reid, and Sam Bhembe; co-executive produced by Keir Pearson and Nicolas Meyer; and co-produced by Bridget Pickering and Luigi Musini. Hotel Rwanda’s behind-the-scenes crew includes director of photography Robert Fraisse, production designers Tony Burrough and Johnny Breedt, editor Naomi Geraghty, costume designer Ruy Filipe, and composer Andrea Guerra. -

On the Roles of Information in the Interaction of Agents in Markets by Pedro Miguel Gardete

On the Roles of Information in the Interaction of Agents in Markets By Pedro Miguel Gardete A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Business Administration in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor J. Miguel Villas-Boas, Chair Professor Ganesh Iyer Professor John Morgan Professor Denis Nekipelov Spring 2011 Copyright 2011 by Pedro Miguel Gardete Abstract On the Roles of Information in the Interaction of Agents in Markets by Pedro Miguel Gardete Doctor of Philosophy in Business Administration University of California, Berkeley Professor J. Miguel Villas-Boas, Chair Markets are rich environments for study. Two features in particular make them attrac- tive settings for the study of the roles of information. First, they are often characterized by a significant amount of uncertainty, an essential ingredient for information to be relevant. Second, strategic interactions abound. Each chapter of this dissertation uses a different ‘lens’ so as to focus on particular roles of information in strategic market settings. First, information is considered in its pure ‘aid to decision-making’ role, in which agents use it to improve their decisions, not only based on the expected future conditions but also on the expected actions of the other agents which in turn depend on the information they are likely to hold. Second, information is considered in its ‘influencer’ and ‘coordinator’ roles. It can be used to influence the decisions of agents which will in turn affect the welfare of the original transmitters, while increasing overall market coordination. Finally, information is considered in its ‘homogenizer’ role, in the sense that actions and preferences may become more similar after its repeated use and subsequent transmission. -

COMPARE BUY Imagine Paying 10%, 20%, Or 25% Per Month on Short Term Loans

FINAL-1 Sat, Mar 4, 2017 3:09:00 PM tvupdateYour Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment For the week of March 12 - 18, 2017 Right and wrong Felicity Huffman stars in “American Crime” INSIDE •Sports highlights Page 2 •TV Word Search Page 2 •Family Favorites Page 4 •Hollywood Q&A Page14 The anthology crime drama created by “12 Years a Slave” (2013) writer John Ridley may not be a ratings beast, but “American Crime” has garnered much critical acclaim for its raw portrayal of difficult subjects. Season 3 puts a spotlight on American labor issues and exploitation, with Felicity Huffman (“Desperate Housewives”), Regina King (“Ray,” 2004) and the rest of the core cast falling admirably into their new roles. The new season of “American Crime” premieres Sunday, March 12, on ABC. WANTED MOTORCYCLES, SNOWMOBILES, OR ATVS COMPARE BUY Imagine paying 10%, 20%, or 25% per month on short term loans. Sounds absurd! Well, people do at pawn shops all the time. Mass pawn shops charge 10% per month SELL WINTER ALLERGIES plus fees. NH Pawn shops charge 20% and more. Example: A $1,000 short term loan TRADE ARE HERE! means you pay back $1,400-$1,800 depending on where you do business. Bay 4 DON’T LET IT GET YOU DOWN PARTS & ACCESSORIES Group Page Shell SALES & SERVICE We at CASH FOR GOLD SALEM, NH charge Motorsports Alleviate your mold allergies this season. 5 x 3” MASS. 0% interest. MOTORCYCLE 1 x 3” Call or schedule your appointment INSPECTIONS online with New England Allergy today. THAT’S RIGHT! NO INTEREST for the same 4 months Borrow $1000 - Pay back $1000. -

2LOVERS Presskit FINAL 2

A James Gray Film Joaquin Phoenix And Gwyneth Paltrow International Distribution International Publicity 2929 International Rogers and Cowan 9100 Wilshire Blvd, Suite 500W 8687 Melrose Avenue, 7th Floor Beverly Hills, CA 90212 Los Angeles, CA 90069 Tel: (310) 309-5200 Tel: (310) 854-8100 Fax: (310) 309-5708 Fax: (323) 854-8143 Contact: Shebnem Askin Contact: Sandro Renz & Laura Chen Cannes Contact: Rogers and Cowan, Relais de la Reine, 42/43 La Croisette 3 rd Floor Tel: +33 (0)4 93 39 01 33 1 TWO LOVERS Following a suicide attempt, a troubled young man moves back into his parents’ Brooklyn apartment and two women enter his life—a beautiful but volatile neighbor trapped in a toxic affair and the lovely daughter of his father's new business partner. Synopsis TWO LOVERS is a classical romantic drama set in the insular world of Brighton Beach, Brooklyn. It tells the story of Leonard (JOAQUIN PHOENIX), an attractive but troubled young man who moves back into his childhood home following a suicide attempt. While recovering under the watchful eye of his worried but ultimately uncomprehending parents (ISABELLA ROSSELLINI and MONI MONOSHOV), he encounters two women in quick succession: There’s Michelle (GWYNETH PALTROW), a mysterious and beautiful neighbor— exotic and out-of-place in Leonard’s staid Brighton Beach neighborhood. But he soon discovers that she too is deeply troubled. Meanwhile, his parents try to set him up with Sandra (VINESSA SHAW), the lovely and caring daughter of the suburban businessman who’s buying out the family drycleaning business. At first resistant to her appeal (and to his family’s pressure), Leonard gradually discovers hidden depths in Sandra. -

Inventory to Archival Boxes in the Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress

INVENTORY TO ARCHIVAL BOXES IN THE MOTION PICTURE, BROADCASTING, AND RECORDED SOUND DIVISION OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Compiled by MBRS Staff (Last Update December 2017) Introduction The following is an inventory of film and television related paper and manuscript materials held by the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress. Our collection of paper materials includes continuities, scripts, tie-in-books, scrapbooks, press releases, newsreel summaries, publicity notebooks, press books, lobby cards, theater programs, production notes, and much more. These items have been acquired through copyright deposit, purchased, or gifted to the division. How to Use this Inventory The inventory is organized by box number with each letter representing a specific box type. The majority of the boxes listed include content information. Please note that over the years, the content of the boxes has been described in different ways and are not consistent. The “card” column used to refer to a set of card catalogs that documented our holdings of particular paper materials: press book, posters, continuity, reviews, and other. The majority of this information has been entered into our Merged Audiovisual Information System (MAVIS) database. Boxes indicating “MAVIS” in the last column have catalog records within the new database. To locate material, use the CTRL-F function to search the document by keyword, title, or format. Paper and manuscript materials are also listed in the MAVIS database. This database is only accessible on-site in the Moving Image Research Center. If you are unable to locate a specific item in this inventory, please contact the reading room. -

Inventing the Abbotts

INVENTING THE ABBOTTS Screenplay by Ken Hixon From the Short Story by Sue Miller March 21, 1996 DRAFT FOR EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES ONLY INVENTING THE ABBOTTS FADE IN: 1EXT. ABBOTT HOME - STREET (HALEY, ILLINOIS) - DAY 1 (LATE SPRING, 1957) OPENING CREDITS ROLL over a TENT MONTAGE -- ASSORTED ANGLES of a group of men hard at work erecting a large striped "big-top" style canvas tent, INCLUDING: The long steel stakes being sledge-hammered into the lawn, practiced hands rapidly rigging the lines, the tall center poles being leveraged upright, the heavy rolled-up sections of canvas being maneuvered into position, and ENDING WITH the canvas being hoisted up the poles as the tent assumes its full and finished form. NEW ANGLE - TENT -- on the front yard of the Abbott mansion. The residence is on Main Street, four blocks from where the commercial district begins. The mature, over-arching trees makes this street of prosperous houses a grand promenade. 2EXT. ABBOTT HOME - STREET - DAY 2 JACEY HOLT and DOUG HOLT walk along the sidewalk on their way to school. Jacey is seventeen; he's as handsome and seemingly self-confident as his younger brother is rumpled and impulsive. Doug is fifteen, a popular culture chameleon who takes on the colors and affectations of whomever his "hero" is at the moment (which presently happens to be Elvis Presley). Jacey stops and stares with open-faced misery at the tent on the Abbott's front yard (the installation of the tent indicates that the Abbott's are having yet another of the many parties they throw every year).