Chapter Four Beyond the Spitfire: Re-Visioning Latinas in Sylvia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toxic Trespass

w omeN 2010 make New Releases movies WMM www.wmm.com Women Make Movies Staff Jen Ahlstrom Finance Coordinator Liza Brice Online Marketing ABOUT & Outreach Coordinator Jessica Drammeh IT/Facilities Coordinator WOMEN MAKE MOVIES Kristen Fitzpatrick A NON-PROFIT INDEPENDENT MEDIA DISTRIBUTOR Distribution Manager Tracie Holder Production Assistance From cutting-edge documentaries that give depth to today’s headlines to smart, Program Consultant stunning fi lms that push artistic and intellectual boundaries in all genres, Stephanie Houghton Educational Sales Women Make Movies (WMM), a non-profi t media organization, is the world’s & Marketing Coordinator leading distributor of independent fi lms by and about women. WMM’s Maya Jakubowicz Finance & Administrative Manager commitment to groundbreaking fi lms continues in 2010 with 24 new, astonishing Cristela Melendez and inspiring works that tackle, with passion and intelligence, everything Administrative Aide from portraits of courageous and inspiring women affecting social change in Amy O’Hara PATSY MINK: AHEAD OF THE MAJORITY, A CRUSHING LOVE, and AFRICA RISING, Offi ce Manager to three new fi lms on issues facing young women today: COVER GIRL CULTURE, Merrill Sterritt Production Assistance ARRESTING ANA, and WIRED FOR SEX, LIES AND POWER TRIPS. Other highlights Program Coordinator include THE HERETICS, a look at the Second Wave of feminism, and two new Julie Whang fi lms in our growing green collection, MY TOXIC BABY and TOXIC TRESPASS. Sales & Marketing Manager Debra Zimmerman Executive Director The WMM collection is used by thousands of educational, cultural, and community organizations across North America. In the last fi ve years dozens Board of Directors of WMM fi lms have been broadcast on PBS, HBO, and the Sundance Channel Claire Aguilar among others, and have garnered top awards from Sundance to Cannes, as Vanessa Arteaga well as Academy Awards®, Emmy Awards®, and Peabody Awards. -

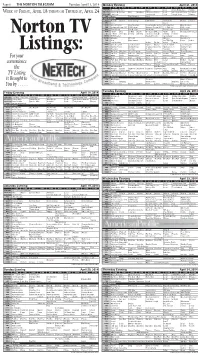

06 4-15-14 TV Guide.Indd

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, April 15, 2014 Monday Evening April 21, 2014 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With Stars Castle Local Jimmy Kimmel Live Nightline WEEK OF FRIDAY, APRIL 18 THROUGH THURSDAY, APRIL 24 KBSH/CBS 2 Broke G Friends Mike Big Bang NCIS: Los Angeles Local Late Show Letterman Ferguson KSNK/NBC The Voice The Blacklist Local Tonight Show Meyers FOX Bones The Following Local Cable Channels A&E Duck D. Duck D. Duck Dynasty Bates Motel Bates Motel Duck D. Duck D. AMC Jaws Jaws 2 ANIM River Monsters River Monsters Rocky Bounty Hunters River Monsters River Monsters CNN Anderson Cooper 360 CNN Tonight Anderson Cooper 360 E. B. OutFront CNN Tonight DISC Fast N' Loud Fast N' Loud Car Hoards Fast N' Loud Car Hoards DISN I Didn't Dog Liv-Mad. Austin Good Luck Win, Lose Austin Dog Good Luck Good Luck E! E! News The Fabul Chrisley Chrisley Secret Societies Of Chelsea E! News Norton TV ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Olbermann ESPN2 NFL Live 30 for 30 NFL Live SportsCenter FAM Hop Who Framed The 700 Club Prince Prince FX Step Brothers Archer Archer Archer Tomcats HGTV Love It or List It Love It or List It Hunters Hunters Love It or List It Love It or List It HIST Swamp People Swamp People Down East Dickering America's Book Swamp People LIFE Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Listings: MTV Girl Code Girl Code 16 and Pregnant 16 and Pregnant House of Food 16 and Pregnant NICK Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Friends Friends Friends SCI Metal Metal Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Metal Metal For your SPIKE Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Jail Jail TBS Fam. -

DGA's 2014-2015 Episodic Television Diversity Report Reveals

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Lily Bedrossian August 25, 2015 (310) 289-5334 DGA’s 2014-2015 Episodic Television Diversity Report Reveals: Employer Hiring of Women Directors Shows Modest Improvement; Women and Minorities Continue to be Excluded In First-Time Hiring LOS ANGELES – The Directors Guild of America today released its annual report analyzing the ethnicity and gender of directors hired to direct primetime episodic television across broadcast, basic cable, premium cable, and high budget original content series made for the Internet. More than 3,900 episodes produced in the 2014- 2015 network television season and the 2014 cable television season from more than 270 scripted series were analyzed. The breakdown of those episodes by the gender and ethnicity of directors is as follows: Women directed 16% of all episodes, an increase from 14% the prior year. Minorities (male and female) directed 18% of all episodes, representing a 1% decrease over the prior year. Positive Trends The pie is getting bigger: There were 3,910 episodes in the 2014-2015 season -- a 10% increase in total episodes over the prior season’s 3,562 episodes. With that expansion came more directing jobs for women, who directed 620 total episodes representing a 22% year-over-year growth rate (women directed 509 episodes in the prior season), more than twice the 10% growth rate of total episodes. Additionally, the total number of individual women directors employed in episodic television grew 16% to 150 (up from 129 in the 2013-14 season). The DGA’s “Best Of” list – shows that hired women and minorities to direct at least 40% of episodes – increased 16% to 57 series (from 49 series in the 2013-14 season period). -

Linda Garcia Merchant 11252 S

Linda Garcia Merchant 11252 S. Normal Avenue, Chicago, IL 60628 c (312) 399-7811 f (773) 629-8170 [email protected] EDUCATION 1982, B.S., with honors, Advertising Design/Photography Western Illinois University 2008-2009, Columbia College Chicago, MFA Film & Video, Follett Fellowship Recipient SELECTED PROFESSIONAL POSITIONS: Producer, Las Pilonas Productions, Phoenix, Arizona 2011 to present Project Coordinator, ‘The Virtual Reunification of the Wisconsin Latina Activist Network’ Course CLS 330: Past and Present Ideologies of the Chican@/Latin@ Movements, University of Wisconsin, Madison 2012 to present Technical Director ‘Chicana Por Mi Raza’ Digital Humanities Project, University of Michigan, 2009 to present Consultant, Somos Latinas Digital Humanities project, 2012 to present Organizing Manager, Voces Primeras, LLC, 2006 to present Web Designer/Developer, Duografix, 2000-2008 Adjunct Professor, Columbia College, Arts, Entertainment & Media Management Department “Management Applications for the Web”, 2000 to 2001 Editor and Content Producer, twotightshoes.net, Chicago, IL 1998 – 2003 Marketing Specialist/IT, Larry Gordon Agency, Chicago, IL 1998 to present Graphics Production Coordinator, 1996 Olympics /Atlanta. GES Exposition Services FILMS/PUBLICATIONS Producer, Director, “Chicana Por Mi Raza Digital Humanities Project: Mujeres del Partido” 2012 Director, ‘Thresholds’, February 2011 Writer, Producer, Four In Grace, 2009, Noelle, 2013 Blogpost, ‘Organized Coraje’, Summer of Feminista, Viva La Feminista, 2012 Producer, Co-director, ‘The A Word’, 2011 Blogpost, ‘Chicanas who spoke out and inspire’, Summer of Feminista, Viva La Feminista, 2011 Producer, Director, ‘Amigas! Fifteen Years of Amigas Latinas’ 2010 Producer, Co-director, ‘Palabras Dulces, Palabras Amargas’ (Sweet Words, Bitter Words) 2009 “From Ava Gardner to Mis Nalgas: The Story of My Brown Skinned Sexuality”, Dialogo, DePaul University Press, 2009. -

T H E C O M B at IV E P H a SE C Heck Y U W Ebsite for in Form Ation

PHASE COMBATIVE THE May 6–June 25, 2017 6–June 25, May The Combative Phase takes its title from an essay by Teshome Gabriel as ‘speaking for,’ as in politics, and representation as ‘representation,’ as in The university and the cinema are not dissimilar institutions. They make 23 titled “Towards a Critical Theory of Third art or philosophy.” 23 comparable claims to be spaces of revelation and of enlightenment. In 19 Teshome Gabriel, “Towards Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, World Films.”19 This text draws on the writing a Critical Theory of Third World “Can the Subaltern Speak?” 1969, a pivotal year for this exhibition, Noël Burch coined the unwieldy Films,” Questions of Third Cinema, Colonial Discourse and Post-Colonial of Frantz Fanon on decolonization, and ed. Jim Pines and Paul Willemen The temporal, spatial, and socio-political Theory: A Reader, eds. Patrick term “institutional mode of representation (IMR)” to characterize the Williams and Laura Chrisman (London: BFI, 1989), 298–316. 1 proposes a “genealogy of Third World film frame of the university—and particularly, (New York: Columbia University dominant standard of totalizing illusionistic representation in cinema. Press, 1994), 70. culture” on a path from “domination to liberation.” Gabriel identifies three its attendant conditions of access to IMR might equally be applied to the 1 Noël Burch, Praxis du Cinéma, phases in this genealogy: firstly, a phase of “unqualified assimilation” in education and means of production—unifies the films exhibited. More figure of the modern university. -

Faculty Directory

FACULTY AND ADMINISTRATORS 2016-2017 CLAYTON ABAJIAN (2014), Lecturer of Nursing, B.S.N., California State University, Sacramento MIKAEL J. ANDERSON (2003), Professor of Construction KIMO AH YUN (1996), Professor of Communication Management; Chair, Department of Construction Studies, B.A., California State University, Management, B.S., M.S., University of California, Sacramento; M.A., Kansas State University; Ph.D., Davis; Registered Professional Engineer; Licensed Michigan State University General Contractor DALE AINSWORTH (2014), Assistant Professor of Health ANDREW K. ANKER (1996), Professor of Design; Chair, Science, B.A., Mississippi College; M.S., Pepperdine Department of Design, B.A., State University of University; Ph.D., Saybrook University New York, Binghamton; M.Arch., Harvard Graduate School of Design; M.Env.Des., Yale PHILLIP D. AKUTSU (2008), Associate Professor of School of Architecture Psychology, B.S., University of Washington; Ph.D., University of California, Los Angeles JUDE ANTONYAPPAN (1998), Professor of Social Work, P.U.C., Holy Cross College, University of Madurai; KRISTEN WEEDE-ALEXANDER (2002), Professor, B.Sc., St. Mary's College; M.S.W., Stella Maris College of Education, Graduate and Professional College, Ph.D., University of California, Berkeley Studies, B.A., University of California, Riverside; M.S., Ph.D., University of California, Davis BEHNAM S. ARAD (1997), Professor of Computer Science, B.S., University of Massachusetts, Lowell; M.S., DALE ALLENDER (2014), Assistant Professor, College of Purdue University, -

Making Movement Through Motion Pictures

Making Movement through Motion Pictures Period films & videos from 1968 to 1975 programmed by Julia Reichert and Ariel Dougherty FILM played a significant role in conjunction with this conference. In fact, a work-in-progress screening of LEFT ON PEARL ignited the whole idea for A Revolutionary Moment. The conference featured two evenings of screenings of documentaries about Second Wave feminism, including Joan Braderman’s “Heretics.” Jennifer Lee’s “Feminist: Stories from Women’s Liberation,” Catherine Russo’s “A Moment in Her Story,” Susie Rivo and the 888 Women’s History Project’s “Left on Pearl,” Liane Brandon’s “Anything You Want to Be,” and excerpts from Mary Dore’s “She’s Beautiful When She’s Angry.” A third evening featured a range of films from the early 1970s, selected by Julia Reichert and Ariel Dougherty. Two workshops focused entirely on women’s filmmaking. Numerous others included film as a component of the context of recording issues of the period. MAKING A MOVEMENT THROUGH MOTION PICTURES PROGRAM NOTES: Films of the Period 1968 – 1975 programmed by Julia Reichert and Ariel Dougherty For A REVOLUTIONARY MOMENT Conference / Boston University Saturday March 29, 2014 7:30 pm GSU Conf Auditorium This selection of films from the period includes documentary, fiction, experimental & animated works from all over the US. These film clips and shorts will introduce viewers to authentic voices from the birth of the Women's Liberation Movement. The works are pointedly a response to omission of voices and /or distortion of viewpoints in mainstream corporate media that still persists today. While here we show only US based work, this movement was international. -

TLC Press Highlights EXTREME COUGAR WIVES December 2013 & January 2014 MY CRAZY OBSESSION

BREAKING aMiSH l.a. DeVIOUS MAIDS SERIES FINALE TLC Press Highlights eXTREMe COUGAR WIVeS December 2013 & January 2014 My CRAZy oBSeSSION Sky 125 I Virgin 167 I BT TV 875 I youView on TalkTalk PLAYER eXTREMe BEAUTy DiSaSTERS HONEY BOO BOO BREAKING AMISH L.A. uk SerieS PreMiere January, 2014 Following the original success of Breaking Amish, TLC UK’s highest rating new series of 2013, Breaking Amish: Los Angeles takes a new group of young Amish and Mennonite adults, as they trade in their old world traditions, this time for the modern temptations and glamour of LA. Will they embrace this new world and the freedom that they’ve always dreamed of, or yearn for the simpler life they left behind? DEVIOUS MAIDS uk SerieS PreMiere - SerieS Finale wednesday 1st January, 10.00pm From Marc Cherry, the creator of Desperate Housewives, and executive producer Eva Longoria, Devious Maids came to TLC this October following its huge success in the US - already commissioned for a second series. The 13-part drama centres on a close-knit group of maids working in the homes of Beverly Hills’ wealthiest and most powerful families. The women come together to uncover the truth when their friend and fellow maid is murdered at the home of her employers. Starring Ana Ortiz (Ugly Betty), Roselyn Sánchez (Rush Hour 2), Dania Ramirez (X-Men: The Last Stand), Judy Reyes (Scrubs) and Susan Lucci (All My Children). In this series finale, Taylor learns she has lost the baby, and tells Michael it’s time to tell Marisol the truth. -

The Intersection of Gender & Ethnicity on Latinas' Workplace Sexual

UCLA Chicana/o Latina/o Law Review Title “WE DON’T THINK OF IT AS SEXUAL HARASSMENT”: The Intersection of Gender & Ethnicity on Latinas’ Workplace Sexual Harassment Claims Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0x57d7tc Journal Chicana/o Latina/o Law Review, 33(1) ISSN 1061-8899 Author Suero, Waleska Publication Date 2015 DOI 10.5070/C7331027616 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California “WE DON’T THINK OF IT AS SEXUAL HARASSMENT”: The Intersection of Gender & Ethnicity on Latinas’ Workplace Sexual Harassment Claims By Waleska Suero* “[T]hat’s right, we don’t think of it as sexual harassment . .”1 In the workplace, sexual harassment is broadly defined as the mak- ing of “unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical harassment of a sexual nature.”2 Workplace sexual harassment may arise as a single occurrence where sexual favors are de- manded in exchange for hiring, promotions, or retention.3 It may also be ongoing in the form of continuous sexually suggestive remarks, looks, or touches.4 Either way, in society there are unequal power dynamics be- tween the sexes that play out in the employment context where unequal power dynamics can result in the threat of job security if the woman addresses the unwelcomed statements or gestures.5 Despite this broad understanding of the term “sexual harassment,” differences in race and ethnicity, gender, class, education, and economic status shape how differ- ent groups experience sexual harassment. The focus of this paper is workplace sexual harassment of wom- en at the intersection of gender and ethnicity, specifically pertaining to Latin American women.6 Challenging the pervasive stereotype of the * Georgetown University Law Center, J.D. -

ST. GERMAIN STAGE JUNE 15-JULY 8, 2017 PLACE a Town in Coastal Maine

JULIANNE BOYD, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR SPONSORED BY Judith A. Goldsmith THE BY BIRDSConor McPherson BASED ON THE SHORT STORY BY DAPHNE DU MAURIER FEATURING Stevie Ray Dallimore Sasha Diamond Kathleen McNenny Rocco Sisto SCENIC DESIGNER COSTUME DESIGNER LIGHTING DESIGNER David M. Barber Elivia Bovenzi Brian Tovar SOUND DESIGNER PROJECTION DESIGNER David Thomas Alex Basco Koch CASTING PRODUCTION STAGE MANAGER Pat McCorkle, CSA Michael Andrew Rodgers BERKSHIRE PRESS REPRESENTATIVE NATIONAL PRESS REPRESENTATIVE Charlie Siedenburg Matt Ross Public Relations DIRECTED BY Julianne Boyd SPONSORED IN PART BY Audrey and Ralph Friedner & Richard Ziter, M.D. THE 2017 ST. GERMAIN SEASON IS SPONSORED BY The Claudia and Steven Perles Family Foundation THE BIRDS is presented by special arrangement with Dramatists Play Service, Inc., New York. ST. GERMAIN STAGE JUNE 15-JULY 8, 2017 PLACE A town in coastal Maine CAST IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE Diane ...........................................................................................Kathleen McNenny* Nat ........................................................................................... Stevie Ray Dallimore* Julia ................................................................................................ Sasha Diamond* Tierney ................................................................................................... Rocco Sisto* "They never saw this one coming, ha? No one ever thought nature was just going to eat us." -Tierney, The Birds, Conor McPherson STAFF Production Stage Manager -

REPRESENTATION of LATINAS1 AS MAIDS on DEVIOUS MAIDS (2013) Fitria Afrianty Sudirman

42 Paradigma, Jurnal Kajian Budaya Representation of Latinas as Maids on Devious Maids, Fitria Afrianty Sudirman 43 REPRESENTATION OF LATINAS1 AS MAIDS ON DEVIOUS MAIDS (2013) Fitria Afrianty Sudirman Abstract This article aims to analyze the representation of Latinas as maids by examining the first season of US television drama comedy, Devious Maids. The show has been a controversy inside and outside Latina community since it presents the lives of five Latinas working as maids in Beverly Hills that appears to reinforce the negative stereotypes of Latinas. However, a close reading on scenes by using character analysis on two Latina characters shows that the characters break stereotypes in various ways. The show gives visibility to the Latinas by putting them as main characters and portraying them as progressive and independent women who also refuse the notion of white supremacy. Keywords Latina, stereotypes, television, Devious Maids. INTRODUCTION Latin Americans have grown to be the largest minority group in the United States (US). According to the 2010 US Census, those identifying themselves as Hispanic/Latino Americans increased by 43% from the 2000 US Census, comprising 16% of the U.S total population. The bureau even expected that by 2050, the Hispanic/Latino population in the U.S. will be 132.8 million or 30% of the total population, which means one out of three Americans is a Hispanic/Latino. However, the increasing number of Latin Americans does not seem to go along with the portrayal of them in the US television. Research shows that they remain significantly under-represented on TV, only 1%-3% of the primetime TV population (Mastro-Morawitz, 2005). -

…About Mike Pniewski

…about Mike Pniewski Born and raised in Los Angeles, Mike has been one of the busiest actors in movies and TV for more than 30 years. Most recently you’ve seen him in Shots Fired, NCIS: New Orleans, Madam Secretary, Longmire, Blue Bloods, Manhunt: Unabomber, Killing Reagan and the Emmy Award winning CBS drama The Good Wife. Mike’s other recent credits include Halt and Catch Fire, Army Wives, Devious Maids, Nashville, Drop Dead Diva, Red Band Society, Banshee and the films The Founder with Michael Keaton and American Made with Tom Cruise. Over the years, Mike has made memorable guest appearances in such projects as The Sopranos, CSI: NY, The Glades, Mean Girls 2, Law & Order: Criminal Intent, CSI: Miami, ER, Runaway Jury, From the Earth to the Moon, Ray and Remember the Titans. He is also one of the stars of Two Soldiers, the 2003 Academy Award winner for Best Live Action Short Film. In addition, Mike is one of the busiest actors around in commercials and voice- overs. His credits include Xerox, Gold Bond, Ford, Wal-Mart, TNT, Sprite, CNN, McDonald's, UPS, Hills Brothers, Georgia Power, Publix, Sudafed, Zoo Atlanta, Chevrolet, Miller Lite, Sun Trust Bank--just to name a few. Mike's training began at UCLA where he graduated in 1983 with a Bachelor of Arts Degree in Theater and also won the Natalie Wood Acting Award. Since then he has studied at the famous Groundling Theater in Hollywood and studied cold reading for several years with Brian Reise. In addition to his acting, Mike is a sought after Speaker and Career Coach as well as Author of his book, “When Life Gives You Lemons, Throw ‘em Back!” You can learn more about it at www.acttowin.com.